Maternity Services Maternity Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Intent to Provide Home Instruction Form

NOTICE OF INTENT TO PROVIDE HOME INSTRUCTION SCHOOL YEAR ________ I am providing notice of my intention to provide home instruction for the child(ren) listed below as provided by §22.1-254.1 of the Code of Virginia, in lieu of public school attendance: Name(s) of Child(ren) Date of Birth Grade FCPS Base School (last, first, middle initial) Level 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. As prescribed in §22.1-254.1 of the Code of Virginia, I have included or will provide the school division with a description of the curriculum, limited to a list of subjects to be studied during the coming school year, and evidence of having met one of the following criteria along with this notice by August 15 of each year. **If I begin home instruction after the school year has started, I will submit this notice as soon as practicable and comply with the other requirements within 30 days of the this notice to the school division. I have a high school diploma or higher credential. (Attach copy of diploma or transcript from high school or post- secondary institution, if not already on file) I have the qualifications prescribed by the Board of Education for a teacher. (Attach copy of your current teaching license or a statement to this effect from the Virginia Department of Education, if not already on file) I have provided a program of study or curriculum to be delivered through a correspondence course, distance learning program or some other manner. (Attach notice of acceptance or evidence of enrollment showing school’s name and address for each child—including child’s name, term(s) for which enrolled, and list of subjects to be studied if the child is enrolled in correspondence course or distance learning program). -

Progress Report

PROGRESS REPORT Donald L. Plusquellic, Mayor YEAREND 2003 CAPITAL INVESTMENT & COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Published May 7, 2004 Compiled by Department of Planning & Urban Development Department of Finance Bureau of Engineering 2003 CAPITAL INVESTMENT AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM TABLE OF CONTENTS PROJECT PAGE PROJECT PAGE TRANSPORTATION 1 Bridge Maintenance 10 Broadway Street Viaduct 11 Arterials/Collectors 1 Carnegie Ave. Bridge over Nesmith Lake Outlet 11 High Street Viaduct 11 Arterial Closeouts 1 Triplett Blvd. Bridge over Springfield Lake Outlet 12 Canton Road Signalization 1 Cuyahoga Street, Phase II 2 CD Public Improvements 12 Cuyahoga Street/Alberti Court 2 Darrow Road 2 Bisson NDA: Bellevue Avenue, et al 12 East Exchange Street/Arc Street Signalization 3 Campbell Street 13 East Market Street Signalization Upgrade 3 CD Area Closeouts 13 East Market Street Widening 3 Future CD Public Improvements 14 Euclid/Rhodes Avenue 4 Chandler Avenue, et al 14 Hickory Street 4 Idaho Street, et al 15 Howard/Ridge/High Streets 4 Kenmore Boulevard 15 Manchester Road 5 Oregon Avenue, et al 15 Newdale Avenue Extension 5 Honodle Avenue, et al 16 North Portage Path 5 Riverview Road Emergency Repairs 6 Concrete Street Repair 16 Sand Run Road 6 Sand Run Road Slope Stabilization 6 Concrete Street Repair Closeouts 16 South Arlington Street Signalization & Resurfacing 7 Hilbish Avenue 17 South Hawkins Avenue 7 South Main Street Widening 8 Expressways 17 Street Lighting Capital Replacement 8 Tallmadge Avenue Signalization 8 Expressway Ramp Repairs 17 Tallmadge Avenue Widening 9 Highway Landscaping 17 West Market Street 9 I-77 Widening 18 Innerbelt Study 18 Bridges 10 North Expressway Upgrade 18 U.S. -

Written Testimony to the Ohio Senate Finance Committee May 13, 2021

Written Testimony to the Ohio Senate Finance Committee May 13, 2021 Testimony from Kristin Warzocha, President and CEO, Greater Cleveland Food Bank and Board Chair, Ohio Association of Foodbanks Good afternoon Chairman Dolan, Vice Chair Gavarone, Ranking Member Sykes, and members of the Senate Finance Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to submit testimony on behalf of the Ohio Association of Foodbanks budget request regarding Amended Substitute House Bill 110. I am Kristin Warzocha, President and CEO at the Greater Cleveland Food Bank. I am also honored to serve as Board Chair for the Ohio Association of Foodbanks. At the Greater Cleveland Food Bank, we work to ensure that everyone in our communities has the nutritious food they need every day. Last year we made possible fifty-five million meals in Ashland, Ashtabula, Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, and Richland Counties. This is not an isolated effort- instead, we partner with more than one thousand food pantries, hot meal programs, libraries, churches, schools, senior centers, and other nonprofits to get food out to those in need. This emergency hunger relief is done in partnership with the eleven other food banks throughout our state, collectively making up the Ohio Association of Foodbanks. Thank you for your longstanding support of the Ohio Food Program and the Ohio Agricultural Clearance Program. These two programs are critical to the health and wellbeing of food-insecure families who lack access to enough food for an active, healthy lifestyle. The need was already high in the Greater Cleveland area before the pandemic began. In 2019, Cleveland had the highest child poverty rate among the fifty largest U.S. -

WR4 Ep 1 Shooting Script Script

WR4 Episode 1 Lilac Amendments 15 07 08 1. 1 SCENE 1 INT HOSPITAL ROOM ANYTIME DAY A 1 THE LIGHTING IS MILKY AND WASHED-OUT AS RACHEL WAKES UP IN HER HOSPITAL BED, WEARING HER HOSPITAL GOWN. SHE LOOKS CONFUSED. THE SILENCE IN THE ROOM IS DEATHLY. SHE THROWS BACK THE SHEETS AND SWINGS HER LEGS OUT OF THE BED. WOOZY, SHE WALKS ACROSS THE ROOM AND OPENS THE DOOR... CUT TO: WR4 Episode 1 Lilac Amendments 15 07 08 2. 2 SCENE 2 INT HOSPITAL CORRIDOR ANYTIME DAY A 2 SHE HAS TO SUPPORT HERSELF ON THE DOOR FRAME AS SHE COMES INTO THE DESERTED, EERILY SILENT CORRIDOR. RACHEL Hello? SHE STARTS TO WALK DOWN THE CORRIDOR AND HESITANTLY PUSHES OPEN ONE OF THE SIDE DOORS AS... RACHEL (cont’d) Is there anyone there? CUT TO: WR4 Episode 1 Lilac Amendments 15 07 08 3. 3 SCENE 3 INT MAIN CORRIDOR ANYTIME DAY A 3 SHE IS SURPRISED WHEN SHE COMES OUT INTO THE MAIN SCHOOL CORRIDOR. CONFUSED AND STILL WEARING HER HOSPITAL GOWN, RACHEL WALKS DOWN THE DESERTED CORRIDOR TOWARDS SOME OPEN DOORS. THE LIGHTS ARE TOO BRIGHT, TOO WHITE. SHE IS ALMOST FLOATING NOW - PROPELLED TOWARDS THE DOORS WHICH LEAD... CUT TO: WR4 Episode 1 Lilac Amendments 15 07 08 4. 4 SCENE 4 INT SCHOOL HALL ANYTIME DAY A 4 ...STRAIGHT INTO THE SCHOOL HALL WHICH IS FULL OF PUPILS AND STAFF - ALL FACING THE FRONT. HOWEVER, AS RACHEL DRIFTS DOWN THE CENTRAL AISLE SOME PEOPLE STARE AT HER WITH OBVIOUS HOSTILITY - BOLTON, DAVINA, JANEECE, TOM, MATT ETC. -

Maternity Matters: Choice, Access and Continuity of Care in a Safe Service DH INFORMATION READER BOX

Maternity Matters: Choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service DH INFORMATION READER BOX Policy Estates HR/Workforce Performance Management IM & T Planning Finance Clinical Partnership Working Document purpose Policy Gateway reference 7586 Title Maternity Matters: Choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service Author Department of Health/Partnerships for Children, Families and Maternity Publication date April 2007 Target audience PCT CEs, NHSS Trust CEs, SHA CEs, Care Trust CEs, Foundation Trust CEs, Medical Directors, Directors of PH, Directors of Nursing, Local Authority CEs, Directors of Adult SSs, PCT PEC Chairs, NHSS Trust Board Chairs, Special HA CEs, Directors of HR, Directors of Finance, Allied Health Professionals, GPs, Communications Leads, Emergency Care Leads, Directors of Children’s SSs, Royal Colleges, Heads of Midwifery, Commissioners, Obstetricians, Midwives Circulation list Voluntary Organisations/NDPBs Description Maternity Matters: Choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service outlines a national framework for local improvements to choice, access and continuity of care in maternity services. It highlights how commissioners, providers and maternity professionals will be able to use the health reform agenda to shape provision to meet the needs of women and their families. A self-assessment tool for commissioners to identify the needs of their population accompanies the document. Cross reference National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services; Every Child Matters: Change for Children; Making it Better: For Mother and Baby Superseded documents N/A Action required N/A Timing N/A Contact details Pat Parris Partnerships for Children, Families and Maternity Wellington House 135–155 Waterloo Road, London SE1 8UG Tel 020 7972 1301 For recipient’s use Contents Foreword 2 Executive summary 5 1. -

1256 Waterloo Road Suffield Ohio 44260 Robert L. Rasnick, Chief Phone 330-628-9240 FAX 330-628-5000 Suffieldfire @ AOL.Com

1256 Waterloo Road Suffield Ohio 44260 Robert L. Rasnick, Chief Phone 330-628-9240 FAX 330-628-5000 SuffieldFire @ AOL.com This is a copy of a letter given to residents when a burning complaint is logged with us. We are here due to a complaint that was received about your open burning. The Akron Regional Air Quality Management District is the enforcing agency pertaining to all types of open burning in our township. The attached brochure contains the regulations that apply in Suffield Township. Please specifically remember the following: We are considered to be “Outside a village or city” (A) No person or property owner shall cause or allow open burning in an unrestricted area except as provided in paragraphs (b) to (c) or this rule or in Section 3704.11 of the Revised Code. (B) Open burning shall be allowed for the following purposes without notification to or permission from the Ohio EPA: (1) Cooking for human consumption (2) Disposal of residential waste or agricultural waste generated on the premises if all of the following conditions are observed: (a) The fire does not create a visibility hazard on the roadways, railroad tracks or air fields; (b) The fire is located at a point on the premises no less than 1000 feet from any inhabited building not located on said premises; (c) The wastes are stacked and dried to provide the best practicable condition for efficient burning; and (d) No materials are burned which contain rubber, grease, asphalt or liquid petroleum products. If you have any questions concerning these regulations, or wish to report someone for illegal open burning, please contact the Air Quality Control Office at 330-375-2480. -

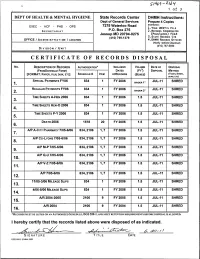

Certificate of Records Disposal

1 of 3 DEPT OF HEALTH & MENTAL HYGIENE State Records Center DHMH Instructions: Dept of General Services Prepare 4 Copies Distribution: EXEC - HCF - PHS - OPS 7275 Waterloo Road P.O. Box 275 I.YOUR UNIT=s FILE SECRETARIAT 2.RECORDS COORDINATOR Jessup MD 20794-0275 (PRGM/ADMIN) FILE (410) 799-1379 3.STATE RECORDS CTR OFFICE / ADMINISTRATION / LOCATION 4.DHMH RECORDS OFFICER (Notify before Disposal) (410) 767-5934 DIVISION / UNIT CERTIFICATE OF RECORDS DISPOSAL No. DESCRIPTION OF RECORDS AUTHORIZATION* INCLUSIVE VOLUME DATE OF DISPOSAL (FROMSCHEDULE FORM) DATES (FT3) DISPOSAL METHOD (TRASH, SHRED, [FORMAT: PAPER, FILM, DISK, ETC] SCHEDULE # ITEM OFRECORDS (BOXES) BURN,ETC) SPECIAL PAYMENTS FY06 834 FY 2006 BINDER 1" JUL-11 SHRED REGULAR PAYMENTS FY06 834 FY 2006 JUL-11 SHRED 2. BINDER 2" TIME SHEETS A-HEN 2006 834 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED TIME SHEETS HEN-0 2006 834 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED TIME SHEETS P-Y 2006 834 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED DEATH 2006 1518 20 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED A/P A-CITY PHARMACY 7/05-6/06 834,2106 1,7 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED A/P CO-LYONS 7/05-6/06 834,2106 1,7 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED 8. A/P M-P 7/05-6/06 834,2106 1,7 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED 9. A/P Q-U 7/05-6/06 834,2106 1,7 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED 10. A/P V-Z 7/05-6/06 834,2106 1,7 FY 2006 1.5 JUL-11 SHRED 11. -

Road Safety Audit Designers Response Baylis Road And

Road Safety Audit Designers Response Baylis Road and Waterloo Road, Cycle Grid Improvements Client: London Borough of Lambeth Document Reference: 1000004381/RSA1-2/SD Date: January 2018 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 This report contains the designer responses to the combined Stage 1/2 Road Safety Audit Report on the proposed cycle grid improvements to the junction of Baylis Road and Waterloo Road, within the London Borough of Lambeth. 1.2 A completed, signed copy by the Project Sponsor is required by the Audit Team Leader for attachment to the master copy of the Final Audit Report. 2 2. RESPONSE TO ITEMS RAISED AT THE STAGE 1 ROAD SAFETY AUDIT Problems Raised Designer’s Response Project Sponsor’s Response 3.1.1 Summary: Risk of side-swipe or shunt type collisions due to inadequate lane widths on Reject. approach to the junction. London Buses have been informally recommending Recommendation: Revisit the design to ensure lane widths of 3.25-3.2m. However, this completely lane widths are adequate on all approaches to contradicts and is overridden by TfLs own LCDS the junction. guidelines, which discourages lane widths between 3.2m-4m in order to prevent vehicles from passing cyclists too closely. The 3m lane widths indicated on Baylis Rd are more than sufficient to accommodate a 2.55m wide bus even when considering the additional clearance required for side wing mirrors. The existing Waterloo Road approaches do have sub-standard nearside lane widths. However the amended lane widths proposed are an improvement on the existing. The minimal difference in lane widths involved is unlikely to increase the risk of collisions. -

Motion Pictures

IAIN COOKE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS GUILD OF MUSIC SUPERVISORS AMY AWARD NOMINATION Best Music Supervision - Documentary GUILD OF MUSIC SUPERVISORS OASIS: SUPERSONIC AWARD Best Music Supervision - Documentary MOTION PICTURES THE BIRD CATCHER Lisa G. Black, Leon Clarance, prods. Garnet Girl Ross Clarke, dir. THE TIME OF THEIR LIVES Sarah Sulick, Azim Bolkiah, prods. Bright Pictures Roger Goldby, dir. COLLIDE Rory Aitken, Ben Pugh, Joel Silver, prods. 42 Films Eran Creevy, dir. OASIS: SUPERSONIC James Gay-Rees, Fiona Neilson, Simon Halfon, prods. Mint Pictures / On The Corner Mat Whitecross, dir. A HUNDRED STREETS Pippa Cross, Idris Elba, Ros Hubbard, prods. CrossDay Films Jim O’Hanlon, dir. BRAHMAN NAMAN Steve Barron, prod. Riley Productions Q, dir. AMY James Gay-Rees, prod. On the Corner Asif Kapadia, dir. DESERT DANCER Pippa Cross, prod. CrossDay Films Richard Raymond, dir. SECOND COMING Polly Leys, Kate Norrish, prods. Hillbilly Productions Debbie Tucker Green, dir. HELLO CARTER Fiona Neilson, prod. Revolution Films Anthony Wilcox, dir. SYRUP Cameron Lamb, prod. Aram Rappaport, dir. SPIKE ISLAND Fiona Nielson, Esther Douglas, prods. Fiesta Productions Matt Whitecross, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 IAIN COOKE TELEVISION WATERSHIP DOWN (mini-series) Rory Aitken, Cecil Kramer, prods. 42 Films / Netflix Noam Murro, dir. FREE REIN Vicki Lutas, Anna McCleery, creators Lime Pictures / Netflix RELLIK (series) Chris Clough, prod. BBC / New Pictures Sam Miller, dir. THE HALCYON (series) Andy Harries, Sharon Hughff, exec prods. Left Bank Pictures Chris Croucher, prod. DOCTOR FOSTER 2 (series) Kate Crowther, prod. Drama Republic Jeremy Lovering, dir. COLD FEET (series) Kenton Allen, Mike Bullen, exec prods. -

The Association Between Midwifery Staffing and Outcomes in Maternity Services in England: Observational Study Using Routinely Collected Data

The association between midwifery staffing and outcomes in maternity services in England: observational study using routinely collected data. Preliminary report and feasibility assessment. Authors Date Vania Gerova Peter Griffiths Simon Jones Debra Bick December 2010 1 Acknowledgements This work was commissioned and financially supported by the Department of Health in England as part of the work of the policy research programme. The views expressed are those of the authors and not those of the Department of Health. We thank Rona McCandlish (Department of Health), Miranda Dodwell (BirthChoice UK) and Rod Gibson (Birth Choice UK) who acted as an advisory group for the work. Contact address for further information: National Nursing Research Unit Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery King‟s College London James Clerk Maxwell Building 57 Waterloo Road London SE1 8WA [email protected] http://www.kcl.ac.uk/schools/nursing/nnru i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................... i Overview ..................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................ 2 Initial objectives and planned work ............................................... 4 Actual work and data assessment ................................................. 4 Discussion ................................................................................... 9 Implications & Future work ........................................................ -

Motor Vehicles and Road Traffic Act

MINISTRY OF THELAWS ATTORNEY OF TRINIDAD GENERAL AND AND LEGAL TOBAGO AFFAIRS www.legalaffairs.gov.tt MOTOR VEHICLES AND ROAD TRAFFIC ACT CHAPTER 48:50 Act 42 of 1934 Amended by 2 of 1936 197/1957 6 of 1974 157/1983 21 of 2000 10 of 1937 115/1958 5 of 1975 4/1985 22 of 2000 37 of 1938 11 of 1959 6/1975 23/1985 2 of 2002 28 of 1944 12 of 1961 31 of 1976 198/1985 *19 of 2007 34 of 1944 11 of 1963 6 of 1977 1 of 1986 30 of 2007 24 of 1945 2/1963 44 of 1977 3/1986 1 of 2009 13 of 1946 21/1963 †8 of 1978 17 of 1986 8 of 2009 40 of 1946 32 of 1964 17 of 1978 *11 of 1988 5 of 2010 2 of 1948 11 of 1965 19 of 1978 37 of 1989 13 of 2010 33 of 1948 27/1966 20 of 1978 9 of 1990 2 of 2013 10 of 1949 36 of 1967 †21 of 1978 4 of 1992 37 of 1949 2/1968 28 of 1978 6 of 1992 5 of 2013 30 of 1951 6/1968 14 of 1979 6 of 1993 12 of 2014 32 of 1951 15 of 1968 47 of 1980 3 of 1994 48/2014 2 of 1952 3 of 1969 185/1980 226/1994 *2 of 2015 30 of 1952 146/1969 2 of 1982 5 of 1995 1 of 2016 47 of 1952 2/1973 8 of 1982 8 of 1996 7 of 2016 20 of 1953 11/1974 146/1982 9 of 1997 18/2016 47 of 1956 13/1974 3/1983 *25 of 1997 47/2016 35 of 1957 27/1974 20 of 1983 35 of 1998 61/2016 *See Note on page 4 †This Act was validated by Act No. -

The Dark Mile

in association with Presents THE DARK MILE Starring Rebecca Calder, Deirdre Mullins, Finlay Macmillan with Paul Brannigan & Sheila Hancock RUNNING TIME: 88 minutes UK THEATRICAL RELEASE: TBC PRESS CONTACT: To be confirmed. The Bridge Films Melanie Dicks M: 07775 912955 Index Logline 3 Synopsis 3 Long Synopsis 3 Production Story 4 What is The Dark Mile? 5 Q&A with Gary Love 6 Principle cast biographies 7 Production team biographies 8 Full cast & crew 10 2 The Dark Mile Production Notes Logline Who’s out there… Synopsis “Deliverance” meets “Rosemary’s Baby” – The Dark Mile is a psychological thriller built around a strong central relationship of two very different yet sympathetic characters. When London couple Louise and Clare book a boat trip to recover from personal tragedy - their trip of a lifetime through the Scottish Highlands soon descends into a hellish ordeal as they delve further into the wilds. They’re confronted by layer upon layer of jeopardy from a variety of sources, but neither our heroes nor the audience can tell which threat will ultimately prove decisive. With many twists along the way - we’re kept guessing until the very end. Combining character driven storytelling with more conventional genre set pieces against the powerfully cinematic Highland backdrop. Long Synopsis Six months on from the tragic miscarriage that buried their unborn daughter, London couple Louise and Claire journey to the waterways of the Great Glen in the Scottish highlands for a boating holiday following a new attempt at IVF. For Louise it is a chance to rest and recuperate from her physical and mental ordeal, and for Claire it is a chance to patch their fragmenting relationship.