SRC 24 Interviewee: Jean Chalmers Interviewer: Brian Ward Date: March 15, 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Paul Andrew Ortiz Director, Associate Professor, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program Department of History 245 Pugh Hall 210 Keene-Flint Hall P.O. Box 115215 P.O. Box 117320 University of Florida University of Florida Gainesville, Florida, 32611 Gainesville, Florida 32611 352-392-7168 (352) 392-6927 (Fax) http://www.history.ufl.edu/oral/ [email protected] Affiliated Faculty: University of Florida Center for Latin American Studies and African American Studies Program Areas of Specialization U.S. History; African American; Latina/o Studies; Oral History; African Diaspora; Social Documentary; Labor and Working Class; Race in the Americas; Social Movement Theory; U.S. South. Former Academic Positions/Affiliations Founding Co-Director, UCSC Center for Labor Studies, 2007-2008. Founding Faculty Member, UCSC Social Documentation Graduate Program, 2005-2008 Associate Professor of Community Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2005-2008 Participating Faculty Member, Latin American and Latino Studies; Affiliated Faculty Member, Department of History. Assistant Professor of Community Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2001-2005. Visiting Assistant Professor in History and Documentary Studies, Duke University, 2000-2001. Research Coordinator, "Behind the Veil: Documenting African American Life in the Jim Crow South," National Endowment for the Humanities-Funded Oral History Project, Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, 1996—2001. Visiting Instructor, African American Political Struggles and the Emergence of Segregation in the U.S. South, Grinnell College, Spring, 1999. (Short Course.) Research Assistant, “Behind the Veil,” CDS-Duke University, 1993-1996. Education: Doctor of Philosophy (History) Duke University, May 2000. Bachelor of Arts, The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington, June 1990. -

Lassiter Cv March 2020 Copy

Curriculum Vitae Matthew D. Lassiter Department of History (734) 546-0799 1029 Tisch Hall [email protected] University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Education __________________________________________________ Ph.D., Department of History, University of Virginia, Charlottesville VA, May 1999. Dissertation: “The Rise of the Suburban South: The ‘Silent Majority’ and the Politics of Education, 1945-1975.” M.A., Department of History, University of Virginia, Jan. 1994. Thesis: “Biblical Fundamentalism and Racial Beliefs at Bob Jones University.” B.A., History, summa cum laude, Furman University, Greenville SC, May 1992. Employment/Teaching ________________________________________ Professor of History, University of Michigan, 2017- Arthur F. Thurnau Professor (since 2015) Associate Professor of History, University of Michigan, 2006-2017 Assistant Professor of History, University of Michigan, 2000-2006 Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Michigan, 2017- Associate Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, 2006-2017 Director of Policing and Social Justice Lab, University of Michigan, 2018- Director of Undergraduate Studies, History Department, 2012-2014 Director of Graduate Studies, History Department, 2006-2008 History 202: “Doing History” (undergraduate methods seminar). History 261: “U.S. History Since 1865” (lecture). History 329: “Crime and Drugs in Modern America” (lecture/‘flipped’ class format). History 364: “History of American Suburbia” (lecture). History 467: “U.S. History Since 1945” (lecture). History/American Culture 374: “Politics and Culture of the Sixties” (lecture). History 196: “Political Culture of Cold War America” (undergraduate seminar). History 399: “Environmental Activism in Michigan” (undergraduate seminar). History 399: “Cold Cases: Police Violence, Crime, and Social Justice in Michigan” (undergraduate HistoryLab seminar) History 497: “War on Crime/War on Drugs” (undergraduate seminar). -

1 Keith Andrew Wailoo July 2013 Mailing Address

Keith Andrew Wailoo July 2013 Mailing Address: Department of History 136 Dickinson Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 phone: (609) 258-4960 e-mail: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT July 2013-present Princeton University Vice Dean Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs July 2010-present Princeton University Townsend Martin Professor of History and Public Affairs Department of History Program in History of Science Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs Center for Health and Wellbeing Sept 09-Jun 2010 Princeton University, Visiting Professor Center for African-American Studies Program in History of Science Center for Health and Wellbeing July 2006-June 2010 Rutgers, State University of New Jersey – New Brunswick Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of History Department of History Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research July 2006-Dec2010 Founding Director, Center for Race and Ethnicity, Rutgers University (An academic unit spanning all disciplines in School of Arts and Sciences, as well as professional schools and campuses, reporting to Vice-President for Academic Affairs) July 2006-Jun2010 P2 (Distinguished Professor), Rutgers University 2006-2007 Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences – Stanford, CA June 2001- Rutgers, State University of New Jersey – New Brunswick June 2006 P1 (Full Professor) Dept. of History/Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research July 1998- Harvard University – Cambridge, MA June 1999 Visiting Professor Dept. of the History of Science/Department of Afro-American Studies 1 July 1992- University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, NC June 2001 Asst. Prof (1992-1997); Assoc Prof (1997-1999); Prof (1999-2001) Department of Social Medicine, School of Medicine Department of History, Arts and Sciences EDUCATION 1992 Ph.D., Department of History and Sociology of Science (M.A. -

Joseph Crespino Jimmy Carter Professor Department of History Emory University

Joseph Crespino Jimmy Carter Professor Department of History Emory University 561 Kilgo St. [email protected] 221 Bowden Hall, 404-727-6555 w Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-4959 f Employment Jimmy Carter Professor of American History, Emory 2014-present University, Atlanta, Georgia Professor, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 2012-2014 Associate Professor, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 2008-2012 Assistant Professor, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 2003-2008 Social Studies Teacher, Gentry High School, Indianola 1994-1996 School District, Indianola, Mississippi Education Stanford University, Stanford, California M.A., Ph.D., Department of History 1996-2002 University of Mississippi, Oxford, Mississippi M.Ed. Secondary School Education 1994-1996 Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois B.A. American Culture 1990-1994 Fellowships, Grants, & Awards Distinguished Lecturer, Organization of American Historians 2012-present Senior Fellow, Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry, 2016-2017 Emory University Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, 2014 Joseph Crespino 2 University of Tübingen, Germany Awards for Strom Thurmond’s America: 2013-2104 Deep South Book Prize, Summersell Center, University of Alabama; Georgia Author of the Year, Biography Prize; Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters, Nonfiction Book Prize National Endowment for the Humanities Summer 2009 Stipend Award Emory University Center for Teaching and Curriculum, Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching Award 2009 Awards for In Search of Another Country: 2008 Lillian Smith Book Award; McLemore Prize, Mississippi Historical Society; Nonfiction Award, Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Ellis Hawley Prize, Journal of Policy History, for 2008 “The Best Defense is a Good Offense: The Stennis Amendment and the Fracturing of Liberal School Desegregation Policy” National Academy of Education/ Spencer Foundation 2006-2007 Postdoctoral Fellowship J.N.G. -

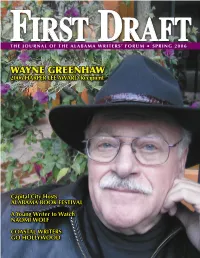

Vol. 12, No.2 / Spring 2006

THE JOURNAL OF THE ALABAMA WRITERS’ FORUM FIRST DRAFT• SPRING 2006 WAYNE GREENHAW 2006 HARPER LEE AWARD Recipient Capital City Hosts ALABAMA BOOK FESTIVAL A Young Writer to Watch NAOMI WOLF COASTAL WRITERS GO HOLLYWOOD FY 06 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBER PAGE President LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn Words have been my life. While other Vice-President ten-year-olds were swimming in the heat of PHILIP SHIRLEY Jackson, MS summer, I was reading Gone with the Wind on Secretary my screened-in porch. While my friends were JULIE FRIEDMAN giggling over Elvis, I was practicing the piano Fairhope and memorizing Italian musical terms and the Treasurer bios of each composer. I visited the local library DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery every week and brought home armloads of Writers’ Representative books. From English major in college to high JAMES A. BUFORD, JR. school English teacher in my early twenties, Auburn I struggled to teach the words of Shakespeare Writers’ Representative and Chaucer to inner-city kids who couldn’t LINDA C. SPALLA read. They learned to experience the word, even Huntsville Linda Spalla serves as Writers’ Repre- DARYL BROWN though they couldn’t read it. sentative on the AWF Executive Com- Florence Abruptly moving from English teacher to mittee. She is the author of Leading RUTH COOK a business career in broadcast television sales, Ladies and a frequent public speaker. Birmingham I thought perhaps my focus would be dif- JAMES DUPREE, JR. fused and words would lose their significance. Surprisingly, another world of words Montgomery appeared called journalism: responsibly chosen words which affected the lives of STUART FLYNN Birmingham thousands of viewers. -

Black Power Beyond Borders Conference

CAUSECENTER FOR AFRICANAMERICAN URBAN STUDIES AND THE ECONOMY BLACK POWER BEYOND BORDERS CONFERENCE ApRIL 8TH - 9TH, 2011 BLACK POWER BEYOND BORDERS This conference aims to expand our understanding of the black power movement geographically, chronologically, and thematically. By examining black power beyond geographic and chronological borders, Black Power Beyond Borders will investigate the multiple meanings of black power both within and beyond the United States. FRIDAY, APRIL 8TH RECEPTION AND REFRESHMENTS 4 PM WELCOME 4:45 PM Dean John Lehoczky, Joe W. Trotter, Nico Slate KEYNOTE ADDRESS 5:00-6:30 PM Barbara Ransby Professor of History and African-American Studies, The University of Illinois at Chicago SATURDAY, APRIL 9TH CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST 8:30 AM PANEL ONE 9:00-10:30 AM Black Power Before “Black Power” Carol Anderson Associate Professor of African American Studies, Emory University (Atlanta, GA) Yevette Richards Jordan Professor of Women’s History, African American History, Labor Studies, and Pan-Africanism George Mason University (Fairfax, VA) Chair: Edda Fields-Black PANEL TWO 10:45-12:15 PM The Panthers Abroad 2 Black Power Beyond Borders Oz Frankel Associate Professor of History, The New School (New York, NY) Robbie Shilliam Senior Lecturer, School of History, Philosophy, Political Science & International Relations Victoria University (Wellington, New Zealand) Chair: Joe W. Trotter LuNCH 12:15 PM PANEL THREE 1:30-3:00 PM Global Black Power from Inside Out Donna Murch Associate Professor of History, Rutgers University (New -

Curriculum Vitae

Keith Andrew Wailoo July 2020 Mailing Address: Department of History 216 Dickinson Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 phone: (609) 258-4960 e-mail: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT July 2010-present Princeton University 2017-present Henry Putnam University Professor of History and Public Affairs Department of History Program in History of Science Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (SoPIA) Center for Health and Wellbeing 2017-2020 Chair, Department of History July 2013-June 2015 Vice Dean, Princeton School of Public and International Affairs 2010-2017 Townsend Martin Professor of History and Public Affairs Sept 09-Jun 2010 Princeton University, Visiting Professor Center for African-American Studies Program in History of Science Center for Health and Wellbeing July 2006-June 2010 Rutgers, State University of New Jersey – New Brunswick Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of History Department of History Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research July 2006-Dec2010 Founding Director, Center for Race and Ethnicity, Rutgers University (An academic unit spanning all disciplines in School of Arts and Sciences, as well as professional schools, reporting to Vice-President for Academic Affairs) July 2006-Jun2010 P2 (Distinguished Professor), Rutgers University 2006-2007 Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences – Stanford, CA June 2001- Rutgers, State University of New Jersey – New Brunswick June 2006 P1 (Full Professor) Dept. of History/Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research July 1998- Harvard University – Cambridge, MA June 1999 Visiting Professor Dept. of the History of Science/Department of Afro-American Studies July 1992- University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, NC June 2001 Asst. -

A Tale of Two Alabamas

File: Hamill Macro Updated Created on: 5/22/2007 2:37 PM Last Printed: 5/22/2007 2:38 PM BOOK REVIEW A TALE OF TWO ALABAMAS Susan Pace Hamill* ALABAMA IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY. By Wayne Flynt.** Awarded the 2004 Anne B. and James McMillan Prize. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 2004. Pp. 602. Illustrations. $39.95. * Professor of Law, University of Alabama School of Law. Professor Hamill gratefully acknowl- edges the support of the University of Alabama Law School Foundation, the Edward Brett Randolph Fund, the William H. Sadler Fund, and the staff at the Bounds Law Library, especially Penny Gibson, Creighton Miller, and Paul Pruitt, and also appreciates the hard work and insights from her “Alabama team” of research assistants, led by Kevin Garrison and assisted by Greg Foster and Will Walsh. I am especially pleased that this Book Review is appearing in the issue honoring my colleague Wythe Holt, whose example and support expanded for me the realm of what scholarship can be and do. ** Professor Emeritus, Auburn University; formerly Distinguished University Professor of History, Auburn University. Flynt is the author of eleven books, which have won numerous awards, including the Lillian Smith Book Award for nonfiction, the Clarence Cason Award for Nonfiction Writing, the Out- standing Academic Book from the American Library Association, the James F. Sulzby, Jr., Book Award (three times), and the Alabama Library Association Award for nonfiction (twice). His most important books include ALABAMA: THE HISTORY OF A DEEP SOUTH STATE (1994), a book he co-authored that is widely viewed as the finest single-volume history of an individual state and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, POOR BUT PROUD: ALABAMA’S POOR WHITES (1989), which also was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and DIXIE’S FORGOTTEN PEOPLE: THE SOUTH’S POOR WHITES (1979), which was reissued in 2004. -

Trouble No More Anthony Grooms Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Faculty Publications 1-2006 Trouble No More Anthony Grooms Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facpubs Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Grooms, Anthony. Trouble No More. Kennesaw GA: Kennesaw State Univ Pr, 2006. Print. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anthony Grooms’s first collection of stories takes place mostly in the South of the 1960s, a time when the “colored” sign at a fast-food restaurant may have been removed, but “still people knew which line was which.” And the talk that animates these vignettes—from lunch counters to juke joints to family dinner tables—is an affecting reminder of the quiet courage, ingrained wariness, and rueful humor with which such individual decisions reshaped an uncertain community. —Alida Becker, The New York Times Book Review These stories all take risks by going into virtually unexplored corners of race relations at a time when critics have declared the subject mined out… Grooms’s stories take us to the center of the phenomenon with an honesty and courage long overdue. —Phil Garner, Atlanta Journal and Constitution It is to Grooms’s credit that he has demonstrated in this collection the insider’s profound knowledge of the history and the struggles of African Americans, while consistently managing to circumscribe his breadth of understanding with a tender story-telling art. -

A Tale of Two Alabamas Book Review

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Essays, Reviews, and Shorter Works Faculty Scholarship 2006 A Tale of Two Alabamas Book Review Susan Pace Hamill University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_essays Recommended Citation Susan P. Hamill, A Tale of Two Alabamas Book Review, 58 Ala. L. Rev. 1103 (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_essays/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Essays, Reviews, and Shorter Works by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. BOOK REVIEW A TALE OF Two ALABAMAS Susan Pace Hamill* ALABAMA IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY. By Wayne Flynt.** Awarded the 2004 Anne B. and James McMillan Prize. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 2004. Pp. 602. Illustrations. $39.95. * Professor of Law, University of Alabama School of Law. Professor Hamill gratefully acknowl- edges the support of the University of Alabama Law School Foundation, the Edward Brett Randolph Fund, the William H. Sadler Fund, and the staff at the Bounds Law Library, especially Penny Gibson, Creighton Miller, and Paul Pruitt, and also appreciates the hard work and insights from her "Alabama team" of research assistants, led by Kevin Garrison and assisted by Greg Foster and Will Walsh. I am especially pleased that this Book Review is appearing in the issue honoring my colleague Wythe Holt, whose example and support expanded for me the realm of what scholarship can be and do. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Raymond Gavins 1. Education Virginia Union

1 Curriculum Vitae Raymond Gavins 1. Education Virginia Union University, History, B.A. magna cum laude, 1964 University of Virginia, American History, M.A., 1967 University of Virginia, American History, Ph.D., 1970 2. Employment and Experience United States Department of State: Summer Intern, 1964 Henrico County, Virginia Public Schools: U.S. History & Government Instructor, 1965-66 Charlottesville-Albemarle Community Action Organization: Instructor, 1968 University of Virginia, Upward Bound Program: Instructor, 1969 Duke University: Assistant, 1970-76, Associate, 1977-91, and Professor of History, 1992-Present Co-Director of Research Project, “Behind the Veil: Documenting African American Life in the Jim Crow South,” Center for Documentary Studies, 1991-Present Director of Graduate Studies, Department of History, 1995-98 Director of Senior Honors Thesis Program, Department of History, 2005-08 3. Awards, Fellowships, and Honors University of Virginia, Cincinnati Historical Fellowship, 1966-67 Southern Fellowships Fund Fellowship, 1968-70 Duke Research Council Regular Grant, 1970-72 National Endowment for the Humanities Younger Humanist Fellowship, 1974 Whitney M. Young, Jr. Memorial Foundation Summer Fellowship, 1975 Rockefeller Foundation Humanities Fellowship, 1978-79 Ford Foundation Minority Postdoctoral Fellowship, 1984-85 Postdoctoral Fellowship, Carter G. Woodson Institute for Afro-American and African Studies, University of Virginia, 1989-90 Julian Francis Abele Award, Duke Black Graduate and Professional Student Association, 1998 Co-recipient, Oral History Association Distinguished Oral History Project Award, 1996 Co-recipient, Multicultural Review Carey McWilliams Book Award, 2002 Co-recipient, Southern Regional Council Lillian Smith Book Award, 2002 Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Fellowship, 2003-04 (Declined) Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy Fellowship, 2003-04 (Declined) Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Fellowship, 2003-04 John W. -

Eight Special Alabamians to Be Honored at Celebration of the Arts Awards on May 22

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 22, 2019 Contact: Barbara Reed Public Information Officer 334-242-5153 [email protected] EIGHT SPECIAL ALABAMIANS TO BE HONORED AT CELEBRATION OF THE ARTS AWARDS ON MAY 22 MONTGOMERY, ALA. - The Alabama State Council on the Arts will honor eight outstanding Alabamians at the “Celebration of the Arts” awards ceremony on Wednesday, May 22, 2019 at 7:30 p.m. The event will take place at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, located at 1 Festival Drive, Montgomery. A coffee and dessert reception will immediately follow the awards ceremony in the lobby of the theatre. The event is FREE and open to the public, but reservations and tickets are required. The Council's “Celebration of the Arts” award program shines a spotlight on the arts in Alabama and on individuals who have made important contributions to our state’s rich cultural landscape. Elliot Knight, Executive Director of the Council stated, "These individuals represent the state’s immense artistic talent, leadership, and generosity that are an integral part of the cultural landscape of Alabama." This year ASCA will be presenting awards to: A Motown recording legend; an acclaimed and prolific author; an educator/poet/prison arts innovator; a story quilt-maker; a visionary mayor; an Indian Classical Dancer and two long-time patrons for the arts. This year's recipients are: Martha Reeves, Eufaula/Detroit, MI – Alabama’s Distinguished Artist Award Jim and Elmore Inscoe, Montgomery – Jonnie Dee Riley Little Lifetime Achievement Award Frye Gaillard, Mobile – Governor's Arts Award Kyes Stevens, Waverly/Auburn – Governor's Arts Award Yvonne Wells, Tuscaloosa – Governor's Arts Award Sudha Raghuram, Montgomery – The Alabama Folk Heritage Award Mayor Tommy Battle, Huntsville – The Council Legacy Award The Alabama Distinguished Artist Award honors a professional artist who is considered a native or adopted Alabamian and who has earned significant national acclaim for their art over an extended period.