Machine Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Regional Economic Development Council Awards

2015 Regional Economic Development Council Awards Governor Andrew M. Cuomo 1 2 Table of Contents Regional Council Awards Western New York .........................................................................................................................12 Finger Lakes ...................................................................................................................................28 Southern Tier ..................................................................................................................................44 Central New York ..........................................................................................................................56 Mohawk Valley ...............................................................................................................................68 North Country .................................................................................................................................80 Capital Region ................................................................................................................................92 Mid-Hudson ...................................................................................................................................108 New York City ............................................................................................................................... 124 Long Island ................................................................................................................................... -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE JANUARY 2019 Name: Alejandro Garcia Address: 303 Crawford Avenue Syracuse, NY 13224 Telephone: Office: (315) 443-5569 Born: Brownsville, Texas April 1, 1940 Academic Unit: School of Social Work Academic Specialization: Social Policy, Gerontology, Human Diversity Education: Ph.D., Social Welfare Policy, The Heller School for Advanced Studies in Social Welfare, Brandeis University (1980) Dissertation title: "The Contribution of Social Security to the Adequacy ` of Income of Elderly Mexican Americans." Adviser: Professor James Schulz. M.S.W., Social Work, School of Social Work, California State University at Sacramento (1969) B.A., The University of Texas at Austin (1963) Graduate, Virginia Satir's International AVANTA Process Institute, Crested Butte, Colorado (1987) Membership in Professional and Learned Societies: Academy of Certified Social Workers American Association of University Professors Council on Social Work Education The Gerontological Society of America National Association of Social Workers Association of Latino and Latina Social Work Educators Professional Employment: October 2015-present Jocelyn Falk Endowed Professor of Social Work, School of Social Work Syracuse University 1983 to present: Professor (Tenured), School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 1994-2002 Chair, Gerontology Concentration, School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Garcia cv p. 2 1999, 2000 Adjunct faculty, Smith College School for Social Work Northampton, MA 1984-91 Faculty, Elderhostel, Le Moyne College, Syracuse, NY 1978-1983 Associate Professor, School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 1975-1978 Instructor, Graduate School of Social Work Boston College, Boston, MA 1977-1978 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Social Work, Graduate School of Social Work, Boston University, Boston, MA 1977-1978 Special Lecturer in Social Policy. -

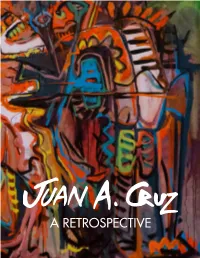

A Retrospective

A RETROSPECTIVE A RETROSPECTIVE This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition Juan A. Cruz: A Retrospective Organized by DJ Hellerman and on view at the Everson Museum of Art, May 4 – August 4, 2019 Copyright Everson Museum of Art, 2019 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019946139 ISBN 978-0-9978968-3-1 Catalogue design: Ariana Dibble Photo credits: DJ Hellerman Cover image: Juan Cruz, Manchas, 1986, oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches, Everson Museum of Art; Gift of Mr. John Dietz, 86.89 Inside front image by Dave Revette. Inside back image by Julie Herman. Everson Museum of Art 401 Harrison Street Syracuse, NY 13202 www.everson.org 2 LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Honorable Minna R. Buck Stephen and Betty Carpenter The Dorothy and Marshall M. Reisman Foundation The Gifford Foundation Laurence Hoefler Melanie and David Littlejohn Onondaga Community College Neva and Richard Pilgrim Punto de Contacto – Point of Contact Samuel H. Sage Dirk and Carol Sonneborn Martin Yenawine 3 FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Spanning five decades, Juan A. Cruz: A Retrospective presents the work of one of Syracuse’s most beloved artists. Juan Cruz settled in Syracuse in the 1970s and quickly established himself as an important part of the local community. He has designed and painted numerous murals throughout the city, taught hundreds of children and teens how to communicate their ideas through art, and assumed the role of mentor and friend to too many to count. Juan’s art, and very person, are part of the fabric of Syracuse, and it is an honor to be able to share his accomplishments with the world through his exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art. -

9New York State Days

NEW YORK 3 REGIONS. 3 NIGHTS EACH. 9 INCREDIBLE DAYS. Explore a brand new self driving tour from New York City all STATE IN the way across the state, including the Hudson Valley, Syracuse and Buffalo Niagara. Countless sites. Countless memories. DAYS See New York State in 9 days. To book your reservation, contact your local travel agent or tour provider. DAY 1-3 HUDSON VALLEY DAY 4-6 SYRACUSE DAY 7-9 BUFFALO NIAGARA 9DAYS 1-3 IN THE HUDSON VALLEY Dutchess County Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Hudson River views, Great Estates, farms & farm markets, FDR Presidential Library & Museum is America’s first events and festivals, cultural & culinary attractions, presidential library and the only one used by a sitting president. boutique & antique shopping – only 90 minutes from NYC! FDR was the 32nd President of the U.S. and the only president dutchesstourism.com elected to four terms. He was paralyzed by polio at age 39, led the country out of the Great Depression, and guided America The Culinary through World War II. fdrlibrary.org Institute of Eleanor Roosevelt’s Val-Kill is the private cottage home of one America of the world’s most influential women. nps.gov/elro The premier culinary Vanderbilt Mansion is Frederick W. Vanderbilt’s Gilded Age home school offers student- surrounded by national parkland on the scenic Hudson River. guided tours and dining nps.gov/vama at four award-winning restaurants. Walkway Over ciarestaurantgroup.com the Hudson The bridge (circa 1888) is a NY State Historic Park; 64.6m above the Hudson and 2.06km across, making it the world’s longest elevated pedestrian bridge. -

800 & 801 Van Rensselaer Street

800 & 801 Van Rensselaer Street Syracuse | New York PARCEL A PARCEL B Executive Summary OfferingOverview Property Overview Market Overview PARCEL A PARCEL B Executive Summary OfferingOverview Property Overview Market Overview Syracuse, New York Jones Lang LaSalle Brokerage, Inc. (Seller’s Agent) is the exclusive agent for owner and seller (“Seller”) of two (2) land sites consisting of 5.10 and 3.47 acres respectively and located in Syracuse, New York (“Property”). Please review, execute and return the Confidentiality Agreement to receive access to the confidential property information. Please contact us if you have any questions. The designated agent for the Seller is: James M. Panczykowski Senior Vice President Jones Lang LaSalle Brokerage, Inc. 551-404-8834 [email protected] Executive Summary OfferingOverview Property Overview Market Overview Disclaimer This Brochure is provided for the sole purpose of allowing a potential investor to evaluate whether there is interest in proceeding with further discussions regarding a possible purchase of or investment in the subject property (the Property). The potential investor is urged to perform its own examination and inspection of the Property and information relating to same, and shall rely solely on such examination and investigation and not on this Brochure or any materials, statements or information contained herein or otherwise provided. Neither Jones Lang LaSalle, nor any of its partners, directors, officers, employees and agents (Sales Agent), nor the owner, its partners or property manager, make any representations or warranties, whether express or implied, by operation of law or otherwise, with respect to this Brochure or the Property or any materials, statements (including financial statements and projections) or information contained herein or relating thereto, or as to the accuracy or completeness of such materials, statements or information, or as to the condition, quality or fitness of the Property, or assumes any responsibility with respect thereto. -

Circuit : a Video Invitational at the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York»

Vito Acconci, New York David Atwood, Boston John Baldessari, Santa Monica, California Born 1940, New York Born 1942 . Boston Born 1931, National City, California Cal Arts Faculty Sonnabend Gallery, New York WGBH-TV, Boston Face Off (15 min . B&W ), Overtone (15 min . B&W) selections from Mixed Bag. Jeremy Steig, and, The Birth of Art and Other Sacred Tales (30 min . Maipieri Quartet (20 min . C) B&W I CIRCUIT: A VIDEO INVITATIONAL AT THE EVERSON MUSEUM OF ART, SYRACUSE, NEW YORK The rapid development of video as an accessible artist's medium has exhibition of this 32 hour package was held in the Spring of 1973 at the raised the question of its practicality in a system with no real support or Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York ; the Henry Gallery of the distribution structure and hence a limited viewing public . The lack of University of Washington in Seattle ; and at the Cranbrook Academy of applicable models, petty rivalries and grant competition are minor Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan . These showings are to be problems compared to the lack of an inexpensive distribution format . followed by exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum, The Green- Many artists have found they have over-estimated their demand by ville County Museum in South Carolina, and other museums still un- support industries (cable television and audio recording concerns), confirmed as of this writing . Additional financing was also provided by and that these industries intend to develop these systems at a pace The New York State Council on the Arts . -

Everson Museum of Art Communications Audit Syracuse University PRSSA EDGE Program

Everson Museum of Art Communications Audit Syracuse University PRSSA EDGE Program 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary . 2 Social Media . 3 Internal Partnerships . 5 External Partnerships . 7 Business Development . 8 Conclusion . 12 2 Executive Summary The following report is the initial communications audit conducted by the Syracuse University Public Relations Student Society of America EDGE Program. Freshmen and sophomore students for the EDGE program conducted the following communications audit to outline the current communications practices by it's client, the Everson Museum of Art. The audit is divided into four sections: social media, internal partnerships, external partnerships and business development. Each section outlines the Everson Museum’s current practices in that area. Moving forward, students will take their findings from this audit to develop communications strategies for the Everson Museum. 3 Social Media The social media team conducted the following audit: Instagram • 8,665 followers • #eversonmuseum has 1000+ posts • Diverse feed - Features different art pieces - Features community events • Feed promotes special events • Page follows 1,363 other pages • Address and #eversonmuseum in bio • No link to museum website in bio Facebook • Their rating on Facebook is 4.4 out of 5 (Based on 221 ratings) • 10,384 people like the page • 10,824 people follow this • 2,950 check-ins • Photos include both pictures of the art and community involvement • They also promote events on the page Twitter • 4,619 followers • Follows 454 • Bio: “Modern and contemporary American art with world renowned ceramics collection. First museum designed by I. M. Pei.” • #eversonmuseum #AtTheE • Last Post today (received 2 likes and 0 retweets) • Promotes art and special events 4 LinkedIn • 274 followers • Listed as “Museums and Institutions” • Bio: Modern and contemporary American art museum with a world-renowned ceramics collection. -

Art Resume Plain

ELIZABETH LEADER RESUME Studio: Tri-Main Center, Suite 507 2495 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14214 Home: 160 Huntington Avenue Buffalo, NY 14214 716-517-1186 [email protected] www.elizabethleader.com SELECTED SOLO & TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 Glenn & Awdry Flickenger Arts Center, Nichols School, A Rising Tide, Buffalo, NY 2017 Studio Hart, CODA (with David Buck and Bob Collignon), Buffalo, NY 716-GAL-LERY, Larkinville, The Secret Life of City Crows, Buffalo, NY 2016 Peter A. and Mary Lou Vogt Art Gallery, Canisius College, Discarded Ancestors, Buffalo, NY 2015 Octagon Gallery, Patterson Library, Crossings, (with Ann Parker), Westfield, NY 2013 Larkin at Exchange Gallery, Out of the Rust-Belt, Buffalo, NY 2011 WNY Book Arts Center, A Sense of Place, (with Amy Greenan), Buffalo, NY Niagara County Community College, Troubled Waters, Sanborn, NY 2010 Center for Coastal Studies, Troubled Waters, Provincetown, MA 2009 Bis4Books, Little Adventures, Orchard Park, NY Garret Club, An Outsider’s View, Buffalo, NY 2008 C.G. Jung Gallery, The Underground River, Buffalo, NY SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 Castellani Art Museum, Niagara University, 20/20 Vision: Women Artists in Western New York, Niagara, NY Carnegie Art Center Buffalo Society of Artists Spring Exhibition, North Tonawanda, NY 2019 Sisti Gallery, Buffalo Society of Artists 125th Catalogue Exhibition, Pendleton, NY River Art Gallery, Mixed Media, North Tonawanda, NY 2018 Rochester Contemporary Art Center, 6x6x2018, Rochester, NY 2017 Schenectady County Historical Society, Life on the -

Call to Artists Art Quilts XXVI: Stitching Stories Due Date: Monday, September 13 at Midnight MST Juror: Ellen M

Call to Artists Art Quilts XXVI: Stitching Stories Due Date: Monday, September 13 at midnight MST Juror: Ellen M. Blalock Ellen M. Blalock, Bang Bang You Dead (left), quilt, commercial cotton fabric, 2019, 44" x 43” Ellen M. Blalock, Middle Passage: America’s Legacy (right), quilt, hand painted silk and nonwoven pellon on canvas, 2020, 56 ¼” x 52” DESCRIPTION Quilts and storytelling have always complemented one another. Quilts are blanketed in the oral tradition from construction and deconstruction to concept, purpose culture and history. What stories do your quilts tell? Are they family stories? Utilitarian stories? Animal stories? Travel stories? Maybe a concept? Or maybe, “I got mad and cut it all up and sewed it back together” stories? Regardless of whether the narrative lies in the imagery of the quilt, the process in which you made it, or the significance of design or purpose, we want to see your story quilts. Submit your most significant work to this annual exhibition of contemporary art quilts, showcasing some of the finest textile art on display in the Southwestern United States. This exhibition will take place at both the Vision Gallery and the Chandler Center for the Arts. Now in its 26th year, this annual exhibition has grown from a local and regional quilt show to a respected vehicle for contemporary works. The yearly exhibition draws national and international entries and allows hundreds of visitors each year to experience quilting as an art form. ABOUT THE JUROR Ellen M. Blalock started quilting over 20 years ago to replace what was taken from her family. -

Arabic Gospels in Italy • Wangechi Mutu • Lorena

US $30 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas November – December 2014 Volume 4, Number 4 Arabic Gospels in Italy • Wangechi Mutu • Lorena Villablanca • Vishnu in the Netherlands • Ukiyo-e Heroes David Hockney • Connecting Seas • Yona Friedman • Ed Ruscha • Gauguin at MoMA • Prix de Print • News November – December 2014 In This Issue Volume 4, Number 4 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Globalism Associate Publisher Evelyn Lincoln 4 Julie Bernatz Gospel Lessons: Arabic Printing at the Tipografia Medicea Orientale Managing Editor Dana Johnson Zoe Whitley 11 International Geographic: Wangechi Mutu News Editor on Paper, Print and Printmaking Isabella Kendrick Carlos Navarrete 16 Manuscript Editor Everyday and Popular Imagery Prudence Crowther in the Prints of Lorena Villablanca Online Columnist Robert J. Del Bontà 20 Sarah Kirk Hanley Engraving India in 17th- and 18th-century Europe Design Director Skip Langer Christina Aube 26 Navigating Difference, Connecting Seas Editorial Associate Andrew Saluti 30 Michael Ferut Defenders of the Floating World Editor-at-Large Prix de Print, No. 8 34 Catherine Bindman Faye Hirsch Cartier Window by Stella Ebner Reviews Julia Beaumont-Jones 36 The Rake’s Progress Laurie Hurwitz 40 27 Square Meters, 1001 Nights Faye Hirsch 42 Ruscha’s Course of Empire Calvin Brown 45 Gauguin at MoMA On the Cover: Coenraet Decker, detail of Matsya (1672), copperplate engraving from Jaclyn Jacunski 49 Philippus Baldeaus, Afgoderye der Oost- Past Partisans Indisch heydenen (Pt. III of Naauwkeurige beschryvinge), Amsterdam: J. Janssonius v. John Murphy 50 Collective Brilliance Waasberge & J. v. Someren. Elleree Erdos 52 This Page: Wangechi Mutu, detail of The Proof: Lingen—Melby—Miller Original Nine Daughters (2012), series of nine etching, relief, letterpress, digital printing, News of the Print World 55 collage, pochoir, hand coloring and handmade Contributors 79 carborundum appliques. -

Eric E. Serritella I Ceramic Artist 1000 Smith Level Rd, #B2, Carrboro, NC 27510 919-240-7703 [email protected]

Eric E. Serritella I Ceramic Artist 1000 Smith Level Rd, #B2, Carrboro, NC 27510 919-240-7703 [email protected] www.ericserritella.com Public Collections • The Mint Museum, Charlotte, NC • Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA • Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY • Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, NY • Burchfield Penney Art Center, The Museum for Western NY Arts, Buffalo State College, NY • Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY • Kamm Teapot Foundation, USA • Cornell University Plantations Visitors Center, Ithaca, NY • Jingdezhen Sanbao Ceramic Arts Institute, China • Shui-Li Snake Kiln and Cultural Park, Taiwan • Bob “Hoff” Hoffman Harmonica Case Collection • The Kessler Collection, Asheville, NC Awards 2013 • Delhom Service League Purchase Award, Potters’ Market Invitational, The Mint Museum, Charlotte, NC 2012 • Award for Innovation, Strictly Functional Pottery National, Lancaster, PA • Finalist – NICHE Award, NICHE magazine, collaboration with glass artist Margaret Neher 2011 • Director’s Award, 73rd Regional Exhibition, Arnot Art Museum, Elmira NY • First Place, 3-D, Southern Tier Biennial, Cattaraugus County Arts Council, Olean, NY 2010 • First Place, Carved Vase Exhibition, Everson Museum and Clayscapes Gallery, Syracuse, NY 2009 • Emerging Artist ‘09, AmericanStyle magazine • Memorial Art Gallery Award of Excellence, Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition, Rochester, NY • Best of Show, 36th Annual Art Festival Beth El, St. Petersburg, FL • Finalist – NICHE Award, NICHE magazine 2008 • Exhibitors’ -

Le Moyne College Syracuse, NY Position Profile Endowed Mcdevitt

Le Moyne College Syracuse, NY Position Profile Endowed McDevitt Chair in Physics McDevitt Center December 2016 Prepared by: Summit Search Solutions, Inc. www.lemoyne.edu Le Moyne College Endowed McDevitt Chair in Physics THE INSTITUTION Sitting on a beautiful 160-acre tree lined campus and located just 10 minutes from downtown Syracuse, in the heart of the state of New York, lies Le Moyne College, an independent college established by the Jesuits in 1946. Its mission is to provide students with a values-based, comprehensive academic program designed to foster intellectual excellence and preparation for a life of leadership and service. Under dynamic presidential leadership, Le Moyne College is evolving into a nationally acclaimed college of liberal arts and sciences that draws students from across the U.S. and abroad. Le Moyne is the second youngest of the 28 Jesuit colleges and universities in the United States and the first to open as a co-ed institution. Le Moyne offers more than 700 courses leading to Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degrees in more than 30 different majors. Le Moyne also provides courses of study leading to a master’s in business administration, education, nursing, occupational therapy, physician assistant studies, arts administration, information systems, and family nurse practitioner. The College's Center for Continuing Education offers evening degrees, certificate programs and houses the Success for Veteran's Program. The College serves approximately 2,500 undergraduate and 600 graduate students. Le Moyne has a culture that values creativity, innovation, service, and thoughtfulness. • The Princeton Review ranked Le Moyne among the top 15 percent of colleges in the nation for the third consecutive year and included the College in its guide, The Best 380 Colleges: 2016 Edition.