A Terrible Honesty: the Development of a Personal Voice in Music Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Napa Valley Dixieland Jazz Society at Grant Hall

The Napa Valley Dixieland Jazz Society presents . New Orleans Jazz, on November 10, 2019 1:00 - 4:00 At Grant Hall - Veterans’ Home Yountville, CA . President’s Message The Flying Eagles We are looking forward a dandy afternoon with The Flying Eagles Jazz Band on Sunday, Nov 10. With all the power outages, the hor- ...The Flying Eagles Jazz rific fire and all the upset, it will be good to lift spirits with this lively, Band was formed at the high energy and talented band. Sacramento Trad Jazz Adult Camp in 2010. While this As you know from our last gig, the tavern is open - however, be sure band was the “new kid on to keep in mind that alcohol is not allowed outside the tavern, so the block,” the band plays must be consumed in the tavern. We are working to have it avail- as if they have been to- able during our gigs in Grant Hall, but that is still up in the air. But, it's great to have the bar open and drinks available to all who gether for years! The style want to imbibe. Water will be provided in Grant Hall. runs the gamut of Tradi- tional Jazz styles, from the Original Dixieland Jazz Band to King I am hopeful that food will be available in the cafe/tavern, but don't Oliver, Fats Waller to a more modern-style Dixieland made famous have a definite word yet, so if you want to bring food, you're wel- by Kenny Ball. The band also plays slow blues favorites, up- come to do so - or take the chance the cafe will finally be open. -

Fill Your Summer with Music Draft

FILL YOUR SUMMER WITH MUSIC DRAFT SUMMER 2020 CLASSICAL | JAZZ | FOLK | POP | WORLD = THE MEMORABLE ROCKPORT MUSIC EXPERIENCES EXPERIENCE DEMAND AN INSPIRED • World-class artists EXCEPTIONAL from around the globe • stellar acoustics SPACE. • engaging and accessible community events for all ages INTIMATE • A warm, inviting setting for an unparalleled "…beautiful to the eye concert experience as well as the the ear" The New York Times • Salon-like setting evoking ©Acadia Mezzofanti ©Acadia late night cabarets, jazz clubs and Celtic sessions CONTENTS 5 SEASIDE 39th Annual • Gorgeous harbor views ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL • Picturesque New England June 12–July 12 | August 7-9 coastal village 18 Ten years ago, the opening of the Shalin Liu 9th Annual ROCKPORT JAZZ FESTIVAL Performance Center brought a much-anticipated July 26–August 2 dream to reality for Rockport Music. Originally founded as a chamber music festival in the 80’s, 21 Rockport Music’s new concert hall has truly SUMMER AT ROCKPORT surpassed all expectations. With the opening of Jazz, Folk, Pop & World the hall, the organization has seen exponential May–September growth into multiple musical genres, hosted 28 broadcast events from around the world, and is 2nd Annual ROCKPORT CELTIC FESTIVAL YEAR-ROUND considered “one of the most beautiful halls in OFFICIAL the country.” This year we celebrate the 10th August 27–30 PARTNERS EXCLUSIVE REALTOR anniversary of its opening with a spectacular 30 OFFICIAL HOTEL OFFICIAL TRANSPORTATION summer gala on June 5. We hope you'll join us! -

Ryedale Jazz Festival 2014 Ryedale Jazz Festival 2014

RYEDALE JAZZ FESTIVAL 2014 RYEDALE JAZZ Sun 20th Spirituals Concert, 2.30 St Peter & St Pauls Thurs 24th 7.30pm Swale Valley Stompers Ryedale Jazz, formed in 2000, are the resident band of Started in 1978, and still with two founder members FESTIVAL 2014 Ryedale Jazz Society. Their growing reputation has earned playing, their Trad Jazz style has evolved to include them appearances at Barnsley and Leeds jazz clubs, and elements of swing and other rhythms. Their resultant blend Sunday 20th: St Peter & St Pauls Church at Staithes and Ryedale Festivals, as well as many local of music creates a relaxed and happy style guaranteed to All other performances take place at the private and charity events. After last year’s very successful please both purists and jazz ‘newbies’. SVS have appeared Pickering Memorial Hall YO18 8AA Church Concert they are invited back to give another set of at festivals at home and abroad, and still maintain their spirituals and gospel music their straightforward ‘trad jazz’ Osmotherly residency. interpretation. Find out more from www.ryedalejazz.com . Fri 25th 2pm The Vieux Carré Jazzmen Ryedale Jazz Festival MEMORIAL HALL An extremely busy band maintaining three weekly Mon 21st 7:30pm Gavin Lee’s New Orleans Jazz Band residencies, and many festival appearances, this group Durham-based clarinettist Gavin Lee leads this nationally- has been going since 1954. They play with verve and acclaimed band which specializes in the authentic traditional enthusiasm and their repertoire covers the whole spectrum jazz music of the “Crescent City”. Their energetic and of traditional jazz, from rags and pop to blues and original interpretations of rarely-heard classic tunes are marches, with influences from such greats as Armstrong perfect for listening - and dancing! and Williams. -

Decades of Jazz

k UNIVERSITYOF NEW HAI'PSHIRE OUR THIRTY-FOURTHPROGRAM RAY SMITH'S DECADESOF JAZZ Featurlng: JIMMYMAZZY ..... Banio,Vocals JEFFHUGHES ... Cornel JOHN BATTIS .. Clarinel RICHARDGIORDANO .... Piano ALEHRENFRIED .... .. ... Bass RAYSMITH ...... Drums SPONSOREDBY THE DEPARTMENTOF MUSIC, AND THENEW HAMPSHIRE LIBBABYOF TRADITIONALJAZZ 8 PM. MONDAY MARCH1'1, 1985 STRAFFORDROOM MEMORIALUNION DUBHAM,NEW HAMPSHIRE THE ARTISTS RAYSMITH'S DECADES OF JAZZ To the uninitiated,the nom de plumeol tonight'sensemble might seem puzzling; despite the imaginaliveif seldomaccuratery descriptive designations attached to popurir groupsof today,it is hardlycommon to namea jazzcombo for a time span.The secret.of course. liesin anolherof the mullipleprofessional identities of its leader.Rav smith's radio oro- gram,similarly titled, has beenbroadcast weekly on WGBH-FMin Bbstonfor 13vears (Fridayevenings at 6:30),forrowing an equivalentnumber of yearson suburbansiations. lt servesas a modelof intelligentand interestingprogramming; jazz emerges as a diverse panoramaof individualand collectiveeftorts far richerin varietvand detailthan the star- consciousmentality of so many currentpresentations ever reveals. And Ray'sprimary source ot material is his copious personalrecord collection, a resourcehe has been devel- oping with loveand wisdomsince 1936. Tonight'sprogram will certainlybe informedby the samebreadth ot perspectiveand good humor that is found in Bay'sbroadcasts, and his commentsabout each selection will illumi- nateus aboutthe wealthot the heritage.Many of us -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

Norway's Jazz Identity by © 2019 Ashley Hirt MA

Mountain Sound: Norway’s Jazz Identity By © 2019 Ashley Hirt M.A., University of Idaho, 2011 B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Musicology. __________________________ Chair: Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz __________________________ Dr. Bryan Haaheim __________________________ Dr. Paul Laird __________________________ Dr. Sherrie Tucker __________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong-Cruz The dissertation committee for Ashley Hirt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: _____________________________ Chair: Date approved: ii Abstract Jazz musicians in Norway have cultivated a distinctive sound, driven by timbral markers and visual album aesthetics that are associated with the cold mountain valleys and fjords of their home country. This jazz dialect was developed in the decade following the Nazi occupation of Norway, when Norwegians utilized jazz as a subtle tool of resistance to Nazi cultural policies. This dialect was further enriched through the Scandinavian residencies of African American free jazz pioneers Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and George Russell, who tutored Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek. Garbarek is credited with codifying the “Nordic sound” in the 1960s and ‘70s through his improvisations on numerous albums released on the ECM label. Throughout this document I will define, describe, and contextualize this sound concept. Today, the Nordic sound is embraced by Norwegian musicians and cultural institutions alike, and has come to form a significant component of modern Norwegian artistic identity. This document explores these dynamics and how they all contribute to a Norwegian jazz scene that continues to grow and flourish, expressing this jazz identity in a world marked by increasing globalization. -

A Little More Than a Year After Suffering a Stroke and Undergoing Physical Therapy at Kessler Institute Buddy Terry Blows His Sax Like He Never Missed a Beat

Volume 39 • Issue 10 November 2011 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Saxman Buddy Terry made his first appearance with Swingadelic in more than a year at The Priory in Newark on September 30. Enjoying his return are Audrey Welber and Jeff Hackworth. Photo by Tony Mottola. Back in the Band A little more than a year after suffering a stroke and undergoing physical therapy at Kessler Institute Buddy Terry blows his sax like he never missed a beat. Story and photos on page 30. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Pee Wee Dance Lessons. 3 Jazz Trivia . 4 Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 Prez Sez September Jazz Social . 51 CD Winner . 52 By Laura Hull President, NJJS Crow’s Nest . 54 New/Renewed Members . 55 hanks to Ricky Riccardi for joining us at the ■ We invite you to mark your calendar for “The Change of Address/Support NJJS/Volunteer/JOIN NJJS . 55 TOctober Jazz Social. We enjoyed hearing Stomp” — the Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp about his work with the Louis Armstrong House that is — taking place Sunday, March 4, 2012 at STORIES Buddy Terry and Swingadelic . cover Museum and the effort put into his book — the Birchwood Manor in Whippany. Our Big Band in the Sky. 8 What a Wonderful World. These are the kinds of confirmed groups include The George Gee Swing Dan’s Den . 10 Orchestra, Emily Asher’s Garden Party, and Luna Stage Jazz. -

Jazzslam Jazz Supports Language Arts & Math

JazzSLAM Teacher’s Guide JazzSLAM Jazz Supports Language Arts & Math JazzSLAM TEACHERS: We hope that you and your students enjoyed the JazzSLAM presenta- tion at your school. This guide will help you reinforce some of the concepts we presented and will give you more information for your students about the music of jazz! What is Jazz and Where Did It Come From? Jazz and Blues are types of music that are totally American. Early jazz and blues tunes evolved out of the Southern slaves’ tradition of “call & response” work songs. Slave ships transported Africans to North America, South America, and the Caribbean islands. Many of the enslaved people came from the Congo and spread the Bamboula rhythm throughout the “New World” The people from the Congo brought the Bamboula rhythm and spread it throughout the Western Hemisphere. In colonial America the Africans worked on farms and plantations. While in the fields, they set a beat and communicated to each other through call-and-responses, called "Field Hollers." Spirituals also used the same strong African rhythms and call-and-response patterns. The simple Field Holler form soon evolved into the 12 bar Blues form. African Americans were freed after the Civil War, and many migrated into New Orleans, Louisiana, considered to be the birthplace of jazz. African-American and Creole musicians, who were either self-taught or schooled in the melodies and harmo- nies of European classical music, played in jazz bands, brass bands, military bands and minstrel shows in New Orleans. Field Hollers, Blues, and Spirituals are the roots of today's jazz and blues music. -

Moving the Big Band Online

Moving the Big Band Online Preparing your students for the future: Capitalizing on the opportunities presented by remote learning. Handout - use your phone camera I. Rationale II. Historical context III. Inertia IV. Student-Driven Possibilities Dr. Derek Ganong V. Opportunities Assistant professor of applied trumpet VI. Ideas and Resources Director of Jazz Boise State University Technology ❖ We live in a digital society ❖ “The Shattered Screen” mentality ❖ What are employers really looking for? ❖ Digital Natives vs. Digitally Enabled - I am the Oregon Trail Generation How Can Digital Audio Workstation Software Enhance Learning? ★ Continuous Reflective Practice ★ More Opportunities for Student Ownership ★ More Opportunities for Collaboration ★ More Room for Creativity ★ Progress can be Planned/Systematic ★ Validation of Musicianship Fundamentals ★ A/V Technology Competency = Career Mobility Ask Yourself! ❖ What value does a jazz band provide to a music department? ➢ The director's perspective ❖ What value does a jazz band represent to a high school? ➢ The administrator’s perspective ❖ What value does a jazz band represent externally? ➢ The parent’s perspective Value assessment: It’s not a surprise that the majority of time spent in a jazz band class is spent preparing for the performance. Typical Director’s Internal Dialogue ❏ Can we get through the tunes without a trainwreck? ❏ Does it sound clean and rehearsed? ❏ Is it obvious that we are doing the typical things that are evident to adjudicators? ❏ Do our soloists sound OK ❏ Are the trumpet bells up(!) ❏ Where the heck is <insert essential ensemble member> ❏ Where the heck is your <item essential to instrument function> ❏ Do we have enough music for the concert? ❏ Did I leave the trumpets with enough gas for pep band...? Nothing on this list is student focused. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

Nomination form International Memory of the World Register THE MONTREUX JAZZ FESTIVAL, CLAUDE NOBS’ LEGACY (Switzerland) 2012-15 1.0 Summary (max 200 words) « It’s the most important testimonial to the history of music, covering jazz, blues and rock ». These are the words that Quincy Jones pronounced to present the preservation and restoration project of one of the musical monuments from the 20th century, the Montreux Jazz Festival Archives. From Aretha Franklin or Ray Charles to David Bowie or Prince, more than 5,000 hours of concerts have been recorded both in audio and video, since the creation of the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1967, by the visionary Claude Nobs. This collection contains many of the greatest names in middle and mainstream Jazz, including Errol Garner, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson to Herbie Hancock. Most of them composed great number of improvised jam sessions extremely rare. Miles Davis played his last performance, conducted by Quincy Jones in 1991. Many artists, like Marvin Gaye, recorded their first and only performance for television in Montreux. This collection of “live” music recordings, ranging from 1967-2012, with universal significance and intercultural dimensions has no direct equal in the world. This musical library traces a timeline of stylistic influences from the early styles of jazz to the present day. In 2007, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) and the Montreux Jazz Festival have decided to join forces to create a unique and first of a kind, high resolution digital archive of the Festival. 2.0 Nominator 2.1 Name of nominator (person or organization) THIERRY AMSALLEM (MONTREUX JAZZ FESTIVAL FOUNDATION) 2.2 Relationship to the nominated documentary heritage MEMBER OF THE MONTREUX JAZZ FESTIVAL FOUNDATION BOARD & OWNER AND CURATOR OF THE MONTREUX JAZZ FESTIVAL AUDIOVISUAL LIBRARY 2.3 Contact person(s) (to provide information on nomination) M. -

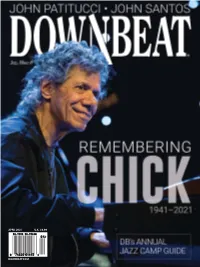

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Jazz Jazz Is a Uniquely American Music Genre That Began in New Orleans Around 1900, and Is Characterized by Improvisation, Stron

Jazz Jazz is a uniquely American music genre that began in New Orleans around 1900, and is characterized by improvisation, strong rhythms including syncopation and other rhythmic invention, and enriched chords and tonal colors. Early jazz was followed by Dixieland, swing, bebop, fusion, and free jazz. Piano, brass instruments especially trumpets and trombones, and woodwinds, especially saxophones and clarinets, are often featured soloists. Jazz in Missouri Both St. Louis and Kansas City have played important roles in the history of jazz in America. Musicians came north to St. Louis from New Orleans where jazz began, and soon the city was a hotbed of jazz. Musicians who played on the Mississippi riverboats were not really playing jazz, as the music on the boats was written out and not improvised, but when the boats docked the musicians went to the city’s many clubs and played well into the night. Some of the artists to come out of St. Louis include trumpeters Clark Terry, Miles Davis and Lester Bowie, saxophonist Oliver Nelson, and, more recently, pianist Peter Martin. Because of the many jazz trumpeters to develop in St. Louis, it has been called by some “City of Gabriels,” which is also the title of a book on jazz in St. Louis by jazz historian and former radio DJ, Dennis Owsley. Jazz in Kansas City, like jazz in St. Louis, grew out of ragtime, blues and band music, and its jazz clubs thrived even during the Depression because of the Pendergast political machine that made it a 24-hour town. Because of its location, Kansas City was connected to the “territory bands” that played the upper Midwest and the Southwest, and Kansas City bands adopted a feel of four even beats and tended to have long solos.