Countywide Pedestrian Plan in 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alameda County Board of Supervisors Personnel, Administration, and Legislation (PAL) Committee LEGISLATIVE POSITION REQUEST FORM

Alameda County Board of Supervisors Personnel, Administration, and Legislation (PAL) Committee LEGISLATIVE POSITION REQUEST FORM Submission deadline is noon on the Monday two weeks prior to the PAL meeting. See FAQ for additional instructions. Title (Bill/Reg. No., Bill/Reg. Title, Author): AB-125 (Rivas) Equitable Economic Recovery, Healthy Food Access, Climate Resilient Farms, and Worker Protection Bond Act of 2022. Version (Date amended): 04/15/2021 Position Requested: Support Current Status of Bill/Regulation (Has the bill been This is a two-year bill currently in the Assembly Committee on referred to committee, or set for hearing? If so, Natural Resources. It has not received a hearing date. when and what committee? Next hearing?) (Where relevant include comment period dates/deadlines): Alignment Shared Visions 10X Goals Operating Principles with Vision ☒ Thriving & Resilient Population ☒ Employment for All ☒ Collaboration 2026: ☐ Safe & Livable Communities ☐ Eliminate Homelessness ☒ Equity ☒ Healthy Environment ☒ Eliminate Poverty and Hunger ☐ Fiscal Stewardship ☐ Prosperous & Vibrant Economy ☐ Crime Free County ☐ Innovation ☐ Healthcare for All ☒ Sustainability ☒ Accessible Infrastructure ☒ Access Alignment with Legislative Platform (i.e. “issue”/plank or Employment for All / “Transition to Circular Economy,” N/A if not in legislative platform) Eliminate Poverty and Hunger / “Food/Nutrition Security,” Accessible Infrastructure / “Climate Change Adaption” Summary (Summary of item, use Legislative Counsel’s Digest, Bill Analysis, -

2010 Urban Water Management Plan

2010 URBAN WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN December 15, 2010 Zone 7 Water Agency Livermore, CA 2010 URBAN WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared by: Zone 7 Water Agency 100 North Canyons Parkway Livermore, CA 94551 (925) 454-5000 Version: December 15, 2010 ZONE 7 WATER AGENCY Report Contributors: Kurt Arends, P.E. – Assistant General Manager of Engineering Boni Brewer – Public Information Officer Jarnail Chahal, P.E. – Principal Engineer Jill Duerig, P.E. – General Manager Amparo Flores, P.E. – Associate Engineer JaVia Green – Staff Analyst Matt Katen, P.G. – Principal Engineer Brad Ledesma, P.E. – Associate Engineer Robyn Navarra – Water Conservation Coordinator Sal Segura, P.E. – Associate Engineer Vince Wong, P.E. - Assistant General Manager of Operations Report Contact: Amparo Flores, (925) 454-5019, [email protected] or Brad Ledesma, (925) 454-5038, [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Previous Urban Water Management Plans ........................................................................ 1-1 1.2 The Purpose of the 2010 UWMP ....................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 Plan Contents and Organization......................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Changes from the 2005 UWMP ......................................................................................... 1-2 2. General Service Area ........................................................................................................ -

United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey Geologic Map of the Las Positas, Greenville, and Verona Faults, Easte

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LAS POSITAS, GREENVILLE, AND VERONA FAULTS, EASTERN ALAMEDA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA By DARRELL G, HERD Open-file report 77-689 INTRODUCTION Livermore Valley, a large east-trending valley in eastern Alameda County, California, approximately 50 kn east of San Francisco, is unique in the central Coast Ranges, where all other major valleys trend northwest* Bounded on the west and east by two major right-lateral strike-slip fault zones the Calaveras-Sunol and the Greenville, Liverraore Valley was originally believed to be crossed by other northwest-trending faults, inferred from ground-water level differences and geophysical anomalies (California Dept. Water Resources, 1963, 1966, 1974; Wight, 1974). Recent mapping in Liverraore Valley and surrounding areas (Herd, 1975) has revealed the existence of the Las Positas fault zone, a high-angle, northeast- trending fault zone that forms the southern limit of the valley and extends from La Costa Valley, east of the Calaveras-Sunol fault zone, northeastward to the Greenville fault zone. The Las Positas fault zone is the first reported northeast-trending fault zone in the central Coast Ranges of California with a history of Quaternary movement. Purpose of map This map depicts the geologic setting of the Las Positas and Greenville fault zones, which bound Livermore Valley on the south and east, and the Verona fault, which lies southwest of Liverraore Valley. The map presents a new interpretation of the geology of Livermore Valley and adjoining areas, and contains new subdivisions of the Quaternary stratigraphy. The recency and recurrence of displacements along the three faults is assessed and an interpretation of the tectonic setting of Livermore Valley proposed. -

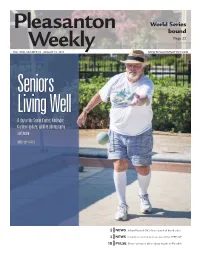

World Series Bound Page 22

World Series bound Page 22 VOL. XVIII, NUMBER 29 • AUGUST 11, 2017 WWW.PLEASANTONWEEKLY.COM Seniors Living Well A day at the Senior Center, Kottinger Gardens update, wildlife photography and more INSIDE THIS ISSUE 5 NEWS School board OKs first round of bond sales 5 NEWS County earns innovation award for STEP-UP 10 PULSE Driver arrested after injury crash on Foothill SIMON COHEN Optical Engineer Severe back pain stopped his life Spine surgery started it again Now he’s back on track Four years ago, Simon injured his back. He tried everything to stop the pain— chiropractors, injections, massage —and nothing worked. After extensive research into spine surgeons and area hospitals, Simon chose a surgeon at Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare, where the team is highly experienced in the latest techniques. His herniated disc was repaired with a small incision and his back pain was gone. Today, his life is back in gear. See his story and find a doctor: ValleyCare.com/Spine Or call: 844-530-0640 Page 2 • August 11, 2017 • Pleasanton Weekly AROUND PLEASANTON PLEASANTON BY JEB BING Rotary: Doing good in Pleasanton he Rotary Club of Pleasanton Winners are invited to attend a Ro- has awarded 12 Pleasanton tary lunch meeting where they are Thigh school students schol- honored for their accomplishment. Life arships totaling $31,950, with an- The two Pleasanton Interact clubs, other $3,000 in scholarship fund- with the one at Amador Valley High ing given to three students by the School sponsored by Downtown Ro- Pleasanton’s annual resource guide coming Rotary Club of Pleasanton North. -

AT Dublin Project Water Supply Assessment

DUBLIN SAN RAMON SERVICES DISTRICT Board of Directors NOTICE OF REGULAR MEETING TIME: 6 p.m. DATE: Tuesday, February 20, 2018 PLACE: Regular Meeting Place 7051 Dublin Boulevard, Dublin, CA AGENDA Our mission is to provide reliable and sustainable water, recycled water, and wastewater services in a safe, efficient, and environmentally responsible manner. 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. PLEDGE TO THE FLAG 3. ROLL CALL – Members: Duarte, Halket, Howard, Misheloff, Vonheeder-Leopold 4. SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS/ACTIVITIES 5. PUBLIC COMMENT (MEETING OPEN TO THE PUBLIC) At this time those in the audience are encouraged to address the Board on any item of interest that is within the subject matter jurisdiction of the Board and not already included on tonight’s agenda. Comments should not exceed five minutes. Speakers’ cards are available from the District Secretary and should be completed and returned to the Secretary prior to addressing the Board. The President of the Board will recognize each speaker, at which time the speaker should proceed to the lectern, introduce him/herself, and then proceed with his/her comment. 6. REPORTS 6.A. Reports by General Manager and Staff Event Calendar Correspondence to and from the Board 6.B. Joint Powers Authority and Committee Reports 6.C. Agenda Management (consider order of items) 7. APPROVAL OF MINUTES 7.A. Regular Meeting Minutes of February 6, 2018 Recommended Action: Approve by Motion 8. CONSENT CALENDAR Matters listed under this item are considered routine and will be enacted by one Motion, in the form listed below. There will be no separate discussion of these items unless requested by a Member of the Board of Directors or the public prior to the time the Board votes on the Motion to adopt. -

MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION for the Tesla Road

Draft INITIAL STUDY/ MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION for the Tesla Road Winery ALAMEDA COUNTY CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Alameda County CDA Planning Division Prepared by: Denise Duffy & Associates Contact: Denise Duffy 947 Cass St. Suite 5 Monterey, California 93940 July 31, 2015 This page left intentionally blank. MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Project: Tesla Road Winery Lead Agency: Alameda County PROJECT DESCRIPTION This Mitigated Negative Declaration (MND), supported by the attached Initial Study (IS), evaluates the environmental effects of a proposed multi‐use wine facility at the northeast corner of the Greenville Road and Tesla Road intersection outside of Livermore, within unincorporated Alameda County, California. The applicant, RAO Company, is proposing the construction of a new 19,944 square foot (sq. ft.) building on the the property. The building’s primary function would be to provide space for wine tasting, tours, and special events, and administrative offices for employees. The building would provide a dedicated space to process wine, serve customers, and hold events. Alameda County is the lead agency for this project and has prepared this MND. FINDINGS An IS has been prepared to assess the projects potential effects on the environment and the significance of those effects. Based on the Initial Study, it has been determined that the proposed project would not have any significant effects on the environment once mitigation measures are implemented. This conclusion is supported by the following findings: 1. The proposed project would have no impact related to greenhouse gas emissions, aesthetics, agricultural resources, hazards/hazardous materials, land use/planning mineral resources, population/housing, public services, and recreation. -

I-680 Sunol SMART Carpool Lane Joint Powers Authority Meeting Agenda Monday, November 4, 2013, 9:30 A.M

Meeting Notice Commission Chair Supervisor Scott Haggerty, District 1 I-680 Sunol Smart Carpool Commission Vice Chair Councilmember Rebecca Kaplan, City of Oakland Lane Joint Powers Authority AC Transit Director Elsa Ortiz Monday, November 4, 2013, 9:30-10:30 a.m. Alameda County 1111 Broadway, Suite 800 Supervisor Richard Valle, District 2 Supervisor Wilma Chan, District 3 Supervisor Nate Miley, District 4 Oakland, CA 94607 Supervisor Keith Carson, District 5 BART Director Thomas Blalock City of Alameda Mission Statement Mayor Marie Gilmore City of Albany The mission of the Alameda County Transportation Commission Mayor Peggy Thomsen (Alameda CTC) is to plan, fund and deliver transportation programs and City of Berkeley projects that expand access and improve mobility to foster a vibrant Councilmember Laurie Capitelli and livable Alameda County. City of Dublin Mayor Tim Sbranti City of Emeryville Public Comments Councilmember Ruth Atkin City of Fremont Public comments are limited to 3 minutes. Items not on the agenda are Mayor William Harrison covered during the Public Comment section of the meeting, and items City of Hayward specific to an agenda item are covered during that agenda item Councilmember Marvin Peixoto discussion. If you wish to make a comment, fill out a speaker card, hand City of Livermore Mayor John Marchand it to the clerk of the Commission, and wait until the chair calls your City of Newark name. When you are summoned, come to the microphone and give Councilmember Luis Freitas your name and comment. City of Oakland Vice Mayor Larry Reid Reminder City of Piedmont Mayor John Chiang Please turn off your cell phones during the meeting. -

BOS Health Committee

ALAMEDA COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS' HEALTH COMMITTEE Monday, September 14, 2015 9:30 a.m. Supervisor Wilma Chan, Chair Location: Board of Supervisors Chambers – Room 512 5th floor Supervisor Keith Carson County Administration Building 1221 Oak Street, Oakland, CA 94612 Summary/Action Minutes I. “Shoo the Flu” Update Attachment Dr. Erica Pan, Director, Division of Communicable Disease Control & Prevention, Alameda County Public Health Department, presented a PowerPoint presentation on “Shoo the Flu”, a program to prevent flu and the spread of flu among children in Alameda County. In Alameda County, there are over 100,000 flu-related illnesses per year, and between 200 to 500 hospitalizations due to the flu. Expenses for flu-related illness in Alameda County are approximately $120 million annually. The flu is preventable thru vaccination. “Shoo the Flu” is a program provided by the Public Health Department in partnership with several other agencies to provide flu vaccination to school children from Pre-K to 5th grade, in select schools across Oakland. The program is free and it requires parental consent. The benefits to vaccinating children at school include: •Increased vaccine coverage in school-aged kids •Decreased community-wide transmission •Reduced absenteeism •Cost savings: direct health care costs and indirect: work days lost •Safe and convenient for parents This program is made possible through grant funding from the Page Foundation and this is the second year of a three-year grant. The State Department of Public Health provides the flu vaccines. Other partners include the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, the California Emerging Infections Program and the Oakland Unified School District. -

BOARD of SUPERVISORS' MEETING, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2019- PAGE 1 Week Not a : the Alameda County Internet Address Is Is Address Internet County Alameda the : LAMEDA

SUMMARY ACTION MINUTES BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Regular Meeting Tuesday, October 29, 2019 COUNTY ADMINISTRATION BUILDING SCOTT HAGGERTY DISTRICT 1 SUPERVISORS’ CHAMBERS RICHARD VALLE, PRESIDENT DISTRICT 2 1221 OAK STREET WILMA CHAN DISTRICT 3 FIFTH FLOOR, ROOM 512 NATE MILEY DISTRICT 4 OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA KEITH CARSON, VICE-PRESIDENT DISTRICT 5 SUSAN S. MURANISHI DONNA ZIEGLER COUNTY ADMINISTRATOR COUNTY COUNSEL MISSION TO ENRICH THE LIVES OF ALAMEDA COUNTY RESIDENTS THROUGH VISIONARY POLICIES AND ACCESSIBLE, RESPONSIVE, AND EFFECTIVE SERVICES. VISION ALAMEDA COUNTY IS RECOGNIZED AS ONE OF THE BEST COUNTIES IN WHICH TO LIVE, WORK AND DO BUSINESS. The Board of Supervisors welcomes you to its meetings and your interest is appreciated. If you wish to speak on a matter on the agenda or during public input, please fill out a speaker slip at the front of the Chambers and turn it in to the Clerk as soon as possible. When addressing the Board, please give your name for the record prior to your presentation. If you wish to speak on a matter not on the agenda, please wait until the President calls for public input at the end of the Regular Calendar. NOTE: Only matters within the Board of Supervisors’ jurisdiction may be addressed. Time limitations shall be at the discretion of the President of the Board. Pursuant to Board Policy: (1) Signs or demonstrations are prohibited during Board meetings; (2) Any Board Member may request a two-week continuance on any item appearing for the first time; (3) All agenda items shall be received by the County Administrator prior to 3 p.m. -

Communityconnection March/April2016 a Community Newsletter from the Alameda County Administrator’S Office

Alameda County CommunityConnection March/April2016 A Community Newsletter from the Alameda County Administrator’s Office CAO’s Corner By Susan S. Muranishi County Administrator Inside This Issue Welcome to our first edition of Alameda County Community Connection, our redesigned community newsletter! We launched Community Connection to bring a fresh, more streamlined look to our newsletter, which we hope will ap- peal to our readers. CAO’s Corner 1 Community Connection will strive to provide you with important information about Alameda County’s activities, along with interesting stories about our employees and departments. We hope you will enjoy this newsletter. Your comments and ideas are always welcome. Please submit any and all com- ments to Guy Ashley at [email protected] or call him at (510) 272-6569. First Responders Praised 1 Quick-Thinking Crucial in Response to Niles Canyon Train Derailment Alameda County Sheriff’s deputies and firefighters take pride in always being ready 12 Inducted into to provide assistance in some of the County’s loneliest and most remote stretches - even in the dead of night. The derailment of a commuter train in Niles Canyon on Women’s Hall of Fame 2 March 7 made it very clear why we are glad they’re out there. County public safety personnel led the emergency response to the incident involv- ing nearly 200 passengers, which turned a routine rainy Monday evening into a composure-testing, adrenaline-surging night shift they will never forget. Firefighter’s Picture Gets “That’s a call that comes over the radio once in a lifetime,’’ said Sheriff’s Deputy Anthony King, one of the first emergency responders to reach the Altamont Com- Worldwide Audience 3 muter Express (ACE) train that was knocked off its tracks by a landslide and sent tumbling into rain-swollen Alameda Creek. -

Recycled Water Trucking and Delivery

DUBLIN SAN RAMON SERVICES DISTRICT Board of Directors NOTICE OF REGULAR MEETING TIME: 6:00 p.m. DATE: Tuesday, September 1, 2015 PLACE: Regular Meeting Place 7051 Dublin Boulevard, Dublin, CA AGENDA (NEXT RESOLUTION NO. 67-15) (NEXT ORDINANCE NO. 338) Our mission is to provide reliable and sustainable water and wastewater services to the communities we serve in a safe, efficient and environmentally responsible manner. BUSINESS: REFERENCE __________________________ Recommended Anticipated Action Time 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. PLEDGE TO THE FLAG 3. ROLL CALL – Members: Duarte, Halket, Howard, Vonheeder-Leopold 4. SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS/ACTIVITIES 5. PUBLIC COMMENT (MEETING OPEN TO THE PUBLIC) At this time those in the audience are encouraged to address the Board on any item of interest that is within the subject matter jurisdiction of the Board and not already included on tonight’s agenda. Comments should not exceed five minutes. Speakers’ cards are available from the District Secretary and should be completed and returned to the Secretary prior to addressing the Board. The President of the Board will recognize each speaker, at which time the speaker should proceed to the lectern, introduce him/herself, and then proceed with his/her comment. 6. REPORTS A. Reports by General Manager and Staff • Event Calendar • Correspondence to and from the Board B. Agenda Management (consider order of items) C. Committee Reports Tri-Valley Water Policy Roundtable July 22, 2015 Financial Affairs August 4, 2015 7. APPROVAL OF MINUTES - Regular Meeting of Executive Services Approve August 4, 2015 Supervisor by Motion Dublin San Ramon Services District Board of Directors Agenda, Regular Meeting, September 1, 2015 Page 2 BUSINESS: REFERENCE __________________________ Recommended Anticipated Action Time 8. -

Alameda CTC Commission Resolution

Commission Chair Mayor Pauline Russo Cutter ALAMEDA COUNTY TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION City of San Leandro Resolution No. 20-007 Commission Vice Chair Councilmember John Bauters City of Emeryville Resolution of the Alameda County Transportation Commission AC Transit Amending the 2014 Transportation Expenditure Plan to Delete the Board Vice President Elsa Ortiz BART to Livermore Project and add the Valley Link Project Alameda County Supervisor Scott Haggerty, District 1 Supervisor Richard Valle, District 2 WHEREAS, by action of the governing body (“Commission”) of Supervisor Wilma Chan, District 3 Supervisor Nate Miley, District 4 Alameda County Transportation Commission (“Alameda CTC”) at a Supervisor Keith Carson, District 5 regular Commission meeting on January 23, 2014, Alameda CTC BART approved the 2014 Transportation Expenditure Plan (“2014 TEP”), and Director Rebecca Saltzman in November 2014, the voters of Alameda County approved City of Alameda Mayor Marilyn Ezzy Ashcraft Measure BB, a sales tax measure intended to provide funding for the 2014 TEP. City of Albany Mayor Nick Pilch WHEREAS, the 2014 TEP allocated $400 million to a project identified City of Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguin as “BART to Livermore,” constituting the first phase of a San Francisco City of Dublin Bay Area Rapid Transit District (“BART”) extension within the I-580 Mayor David Haubert Corridor to serve residents and businesses in that Corridor. City of Fremont Mayor Lily Mei WHEREAS, on May 24, 2018, the BART Board certified the Final City of Hayward Environmental Impact Report for the BART to Livermore project, but Mayor Barbara Halliday declined to approve the project as proposed nor any alternative for City of Livermore Mayor John Marchand the project.