2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acute Toxicity of Cyanide in Aerobic Respiration: Theoretical and Experimental Support for Murburn Explanation

BioMol Concepts 2020; 11: 32–56 Research Article Open Access Kelath Murali Manoj*, Surjith Ramasamy, Abhinav Parashar, Daniel Andrew Gideon, Vidhu Soman, Vivian David Jacob, Kannan Pakshirajan Acute toxicity of cyanide in aerobic respiration: Theoretical and experimental support for murburn explanation https://doi.org/10.1515/bmc-2020-0004 received January 14, 2020; accepted February 19, 2020. of diffusible radicals and proton-equilibriums, explaining analogous outcomes in mOxPhos chemistry. Further, we Abstract: The inefficiency of cyanide/HCN (CN) binding demonstrate that superoxide (diffusible reactive oxygen with heme proteins (under physiological regimes) is species, DROS) enables in vitro ATP synthesis from demonstrated with an assessment of thermodynamics, ADP+phosphate, and show that this reaction is inhibited kinetics, and inhibition constants. The acute onset of by CN. Therefore, practically instantaneous CN ion-radical toxicity and CN’s mg/Kg LD50 (μM lethal concentration) interactions with DROS in matrix catalytically disrupt suggests that the classical hemeFe binding-based mOxPhos, explaining the acute lethal effect of CN. inhibition rationale is untenable to account for the toxicity of CN. In vitro mechanistic probing of Keywords: cyanide-poisoning; murburn concept; CN-mediated inhibition of hemeFe reductionist systems aerobic respiration; ATP-synthesis; hemoglobin; was explored as a murburn model for mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase; mitochondria; diffusible reactive oxidative phosphorylation (mOxPhos). The effect of CN oxygen species (DROS). in haloperoxidase catalyzed chlorine moiety transfer to small organics was considered as an analogous probe for phosphate group transfer in mOxPhos. Similarly, Introduction inclusion of CN in peroxidase-catalase mediated one- electron oxidation of small organics was used to explore Since the discovery of the dye Prussian blue (ferric electron transfer outcomes in mOxPhos, leading to water ferrocyanide, Fe7[CN]18) and the volatile prussic acid formation. -

Juvenile Spondyloarthropathies: Inflammation in Disguise

PP.qxd:06/15-2 Ped Perspectives 7/25/08 10:49 AM Page 2 APEDIATRIC Volume 17, Number 2 2008 Juvenile Spondyloarthropathieserspective Inflammation in DisguiseP by Evren Akin, M.D. The spondyloarthropathies are a group of inflammatory conditions that involve the spine (sacroiliitis and spondylitis), joints (asymmetric peripheral Case Study arthropathy) and tendons (enthesopathy). The clinical subsets of spondyloarthropathies constitute a wide spectrum, including: • Ankylosing spondylitis What does spondyloarthropathy • Psoriatic arthritis look like in a child? • Reactive arthritis • Inflammatory bowel disease associated with arthritis A 12-year-old boy is actively involved in sports. • Undifferentiated sacroiliitis When his right toe starts to hurt, overuse injury is Depending on the subtype, extra-articular manifestations might involve the eyes, thought to be the cause. The right toe eventually skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract and heart. The most commonly accepted swells up, and he is referred to a rheumatologist to classification criteria for spondyloarthropathies are from the European evaluate for possible gout. Over the next few Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG). See Table 1. weeks, his right knee begins hurting as well. At the rheumatologist’s office, arthritis of the right second The juvenile spondyloarthropathies — which are the focus of this article — toe and the right knee is noted. Family history is might be defined as any spondyloarthropathy subtype that is diagnosed before remarkable for back stiffness in the father, which is age 17. It should be noted, however, that adult and juvenile spondyloar- reported as “due to sports participation.” thropathies exist on a continuum. In other words, many children diagnosed with a type of juvenile spondyloarthropathy will eventually fulfill criteria for Antinuclear antibody (ANA) and rheumatoid factor adult spondyloarthropathy. -

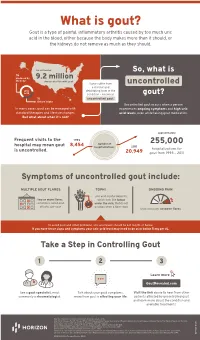

Uncontrolled Gout Fact Sheet

What is gout? Gout is a type of painful, inflammatory arthritis caused by too much uric acid in the blood, either because the body makes more than it should, or the kidneys do not remove as much as they should. An estimated So, what is ⅔ produced by 9.2 million the body Americans live with gout Some suffer from uncontrolled a chronic and uric debilitating form of the acid condition – known as gout? ⅓ uncontrolled gout. dietary intake Uncontrolled gout occurs when a person In many cases, gout can be managed with experiences ongoing symptoms and high uric standard therapies and lifestyle changes. acid levels, even while taking gout medication. But what about when it’s not? approximately Frequent visits to the 1993 number of 255,000 hospital may mean gout 8,454 hospitalizations 2011 is uncontrolled. hospitalizations for 20,949 gout from 1993 – 2011 Symptoms of uncontrolled gout include: MULTIPLE GOUT FLARES TOPHI ONGOING PAIN uric acid crystal deposits, two or more flares, which look like lumps sometimes called gout under the skin, that do not attacks, per year go away when a flare stops that continues between flares To avoid gout and other problems, uric acid levels should be 6.0 mg/dL or below. If you have these signs and symptoms your uric acid level may need to be at or below 5 mg per dL. Take a Step in Controlling Gout 1 2 3 Learn more GoutRevealed.com See a gout specialist, most Talk about your gout symptoms, Visit the link above to hear from other commonly a rheumatologist. -

Effects of Febuxostat on Autistic Behaviors and Computational Investigations of Diffusion and Pharmacokinetics

Effects of Febuxostat on Autistic Behaviors and Computational Investigations of Diffusion and Pharmacokinetics Jamelle M. Simmons Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Engineering Yong W. Lee, Chair Luke E. Achenie Hampton C. Gabler Alexei Morozov Aaron S. Goldstein John H. Rossmeisl November 27, 2018 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, Xanthine Oxidase, Reactive Oxygen Species, Pharmacokinetics, Animal Behavior Copyright 2019, Jamelle M. Simmons Effects of Febuxostat on Autistic Behaviors and Computational Investigations of Diffusion and Pharmacokinetics Jamelle M. Simmons (ABSTRACT) Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong disability that has seen a rise in prevalence from 1 in 150 children to 1 in 59 between 2000 and 2014. Patients show behavioral ab- normalities in the areas of social interaction, communication, and restrictive and repetitive behaviors. As of now, the exact cause of ASD is unknown and literature points to multiple causes. The work contained within this dissertation explored the reduction of oxidative stress in brain tissue induced by xanthine oxidase (XO). Febuxostat is a new FDA approved XO- inhibitor that has been shown to be more selective and potent than allopurinol in patients with gout.The first study developed a computational model to calculate an effective diffu- sion constant (Deff ) of lipophilic compounds, such as febuxostat, that can cross endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by the transcellular pathway. In the second study, male juvenile autistic (BTBR) mice were treated with febuxostat for seven days followed by behavioral testing and quantification of oxidative stress in brain tissue compared to controls. -

Zurampic (Lesinurad)

Market Applicability Market DC GA KY MD NJ NY WA Applicable X X X X X X NA Zurampic (lesinurad) Override(s) Approval Duration Prior Authorization 1 year Quantity Limit Medications Quantity Limit Zurampic (lesinurad) May be subject to quantity limit APPROVAL CRITERIA Requests for Zurampic (lesinurad) may be approved if the following criteria are met: I. Individual has had a previous trial (medication samples/coupons/discount cards are excluded from consideration as a trial) and inadequate response (unable to achieve target serum uric acid levels) to one preferred xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol, febuxostat*); AND II. Individual has hyperuricemia associated with gout; AND III. Individual is unable to achieve target serum uric acid levels while on a xanthine oxidase inhibitor (such as allopurinol or febuxostat*); AND IV. Individual remains symptomatic (such as, but not limited to joint pain, swelling, limited range of motion, erythema) despite use of xanthine oxidase inhibitor; AND V. Individual will continue use of a xanthine oxidase inhibitor in conjunction with Zurampic. *requires prior authorization Zurampic (lesinurad) may not be approved for the following: I. Individual has severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min), end stage renal disease, is on dialysis or is a kidney transplant recipient; OR II. Individual has Lesch-Nyhan syndrome or tumor lysis syndrome. PAGE 1 of 2 08/14/2019 This policy does not apply to health plans or member categories that do not have pharmacy benefits, nor does it apply to Medicare. Note that market specific restrictions or transition-of-care benefit limitations may apply. CRX-ALL-0429-19 Market Applicability Market DC GA KY MD NJ NY WA Applicable X X X X X X NA Note: Zurampic (lesinurad) has a black box warning indicating risk of acute renal failure is more common when Zurampic is used without a xanthine oxidase inhibitor. -

Pegloticase: a New Biologic for Treating Advanced Gout

Drug Evaluation Pegloticase: a new biologic for treating advanced gout Although pharmacologic therapies for hyperuricemia in patients with gout have been well established and are reasonably effective, a small proportion of patients are refractory to treatment and/or present with articular disease so severe as to render standard treatments inadequate. Pegloticase, a PEGylated mammalian urate oxidase with a novel mechanism of action, was recently approved in the USA for the treatment of chronic gout in adult patients refractory to conventional therapy. This paper outlines the development of this unique agent and provides details of the Phase III clinical trial program. A discussion of patient selection, treatment considerations, and risk management for infused pegloticase follows. As a new class of biologic agent offering documented and dramatic effects on lowering serum uric acid and remarkably rapid outcomes in resolving tophi, pegloticase can provide safe and effective management of hyperuricemia and gout for many patients, particularly those who have a high disease burden or who have previously failed to respond to other therapies. KEYWORDS: biologic therapy n chronic gout n hyperuricemia n pegloticase Herbert SB Baraf* & Alan K Matsumoto Among the rheumatic diseases, few are as well have disease that is refractory to current thera- George Washington University, understood as gout. The cause of gout, prolonged pies. These patients often have a chronic, symp- Center for Rheumatology & Bone Research, a Division of Arthritis & hyperuricemia resulting from excess production tomatic, destructive arthropathy, frequent acute Rheumatism Associates, 2730 or decreased excretion of uric acid (UA), was first flares of joint pain and disfiguring tophaceous University Blvd West, Wheaton, MD 20902, USA described by Garrod in the mid-19th century [1]. -

ULORIC Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION -------------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS------------------- These highlights do not include all the information needed to use ULORIC safely and effectively. See full prescribing • Cardiovascular Death: In a CV outcomes study, there was a higher information for ULORIC. rate of CV death in patients treated with ULORIC compared to allopurinol; in the same study ULORIC was non-inferior to ULORIC (febuxostat) tablets, for oral use allopurinol for the primary endpoint of major adverse Initial U.S. Approval: 2009 cardiovascular events (MACE). Consider the risks and benefits of WARNING: CARDIOVASCULAR DEATH ULORIC when deciding to prescribe or continue patients on See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. ULORIC. (1, 5.1) • Gout patients with established cardiovascular (CV) disease • Gout Flares: An increase in gout flares is frequently observed treated with ULORIC had a higher rate of CV death compared to during initiation of anti-hyperuricemic agents, including ULORIC. If those treated with allopurinol in a CV outcomes study. (5.1) a gout flare occurs during treatment, ULORIC need not be discontinued. Prophylactic therapy (i.e., non-steroidal anti- • Consider the risks and benefits of ULORIC when deciding to inflammatory drug [NSAID] or colchicine upon initiation of prescribe or continue patients on ULORIC. ULORIC should only treatment) may be beneficial for up to six months. (2.4, 5.2) be used in patients who have an inadequate response to a maximally titrated dose of allopurinol, who are intolerant to • Hepatic Effects: Postmarketing reports of hepatic failure, allopurinol, or for whom treatment with allopurinol is not sometimes fatal. Causality cannot be excluded. -

Adult Still's Disease

44 y/o male who reports severe knee pain with daily fevers and rash. High ESR, CRP add negative RF and ANA on labs. Edward Gillis, DO ? Adult Still’s Disease Frontal view of the hands shows severe radiocarpal and intercarpal joint space narrowing without significant bony productive changes. Joint space narrowing also present at the CMC, MCP and PIP joint spaces. Diffuse osteopenia is also evident. Spot views of the hands after Tc99m-MDP injection correlate with radiographs, showing significantly increased radiotracer uptake in the wrists, CMC, PIP, and to a lesser extent, the DIP joints bilaterally. Tc99m-MDP bone scan shows increased uptake in the right greater than left shoulders, as well as bilaterally symmetric increased radiotracer uptake in the elbows, hands, knees, ankles, and first MTP joints. Note the absence of radiotracer uptake in the hips. Patient had bilateral total hip arthroplasties. Not clearly evident are bilateral shoulder hemiarthroplasties. The increased periprosthetic uptake could signify prosthesis loosening. Adult Stills Disease Imaging Features • Radiographs – Distinctive pattern of diffuse radiocarpal, intercarpal, and carpometacarpal joint space narrowing without productive bony changes. Osseous ankylosis in the wrists common late in the disease. – Joint space narrowing is uniform – May see bony erosions. • Tc99m-MDP Bone Scan – Bilaterally symmetric increased uptake in the small and large joints of the axial and appendicular skeleton. Adult Still’s Disease General Features • Rare systemic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology • 75% have onset between 16 and 35 years • No gender, race, or ethnic predominance • Considered adult continuum of JIA • Triad of high spiking daily fevers with a skin rash and polyarthralgia • Prodromal sore throat is common • Negative RF and ANA Adult Still’s Disease General Features • Most commonly involved joint is the knee • Wrist involved in 74% of cases • In the hands, interphalangeal joints are more commonly affected than the MCP joints. -

Joint Pain Or Joint Disease

ARTHRITIS BY THE NUMBERS Book of Trusted Facts & Figures 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................4 Medical/Cost Burden .................................... 26 What the Numbers Mean – SECTION 1: GENERAL ARTHRITIS FACTS ....5 Craig’s Story: Words of Wisdom What is Arthritis? ...............................5 About Living With Gout & OA ........................ 27 Prevalence ................................................... 5 • Age and Gender ................................................................ 5 SECTION 4: • Change Over Time ............................................................ 7 • Factors to Consider ............................................................ 7 AUTOIMMUNE ARTHRITIS ..................28 Pain and Other Health Burdens ..................... 8 A Related Group of Employment Impact and Medical Cost Burden ... 9 Rheumatoid Diseases .........................28 New Research Contributes to Osteoporosis .....................................9 Understanding Why Someone Develops Autoimmune Disease ..................... 28 Who’s Affected? ........................................... 10 • Genetic and Epigenetic Implications ................................ 29 Prevalence ................................................... 10 • Microbiome Implications ................................................... 29 Health Burdens ............................................. 11 • Stress Implications .............................................................. 29 Economic Burdens ........................................ -

New Therapeutic Agents Marketed in 2015: Part 4 Amy M

CPE New therapeutic agents marketed in 2015: Part 4 Amy M. Lugo and Brian Park Amy M. Lugo, PharmD, BCPS, BC-ADM, Abstract FAPhA, Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Pharmacy Operations Division, Formu- lary Management Branch, Defense Health Objective: To provide information about the most important properties of new Agency, San Antonio therapeutic agents approved by FDA and first marketed in 2015. Brian Park, PharmD candidate, University of Data sources: Product labeling supplemented selectively with published stud- New England College of Pharmacy, Portland, ies and drug information reference sources. ME Data synthesis: This review covers 11 new therapeutic agents approved by FDA Correspondence: Amy M. Lugo, 7800 and first marketed in the United States in 2015: selexipag, cobimetinib, osimertinib, IH-10 W, Ste. 335, San Antonio, TX 78230; necitumumab, alectinib, insulin degludec, lesinurad, mepolizumab, brexpiprazole, [email protected] cariprazine, and flibanserin. Indications and information on dosage and adminis- Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts tration for these agents are reviewed, as well as efficacy, safety, the most important of interest or financial interests in any product or service mentioned in this article. pharmacokinetic properties, drug interactions, and other precautions. Practical considerations for use of these new agents also are discussed. Whenever possible, Department of Defense (DoD) disclaimer: The information discussed here represents properties of the new drugs are compared with those of older agents marketed for the views of the author and does not neces- the same indications. sarily reflect the views of DoD or the Depart- Summary: Selexipag is the second oral prostacyclin agonist for the treatment ments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. -

Caffeine in the Treatment of Pain

Rev Bras Anestesiol ARTIGOS DE REVISÃO 2012; 62: 3: 387-401 ARTIGOS DE REVISÃO Cafeína para o Tratamento de Dor Cristiane Tavares, TSA 1, Rioko Kimiko Sakata, TSA 2 Resumo: Tavares C, Sakata RK – Cafeína para o Tratamento de Dor. Justificativa e objetivos: A cafeína é uma substância amplamente consumida com efeitos em diversos sistemas e que apresenta farmacoci- nética e farmacodinâmica características, causando interações com diversos medicamentos. O objetivo deste estudo é fazer uma revisão sobre os efeitos da cafeína. Conteúdo: Nesta revisão, são abordados a farmacologia da cafeína, os mecanismos de ação, as indicações, as contraindicações, as doses, as interações e os efeitos adversos. Conclusões: Faltam estudos controlados, randomizados e duplos-cegos para avaliar a eficácia analgésica da cafeína nas diversas síndromes dolorosas. Em pacientes com dor crônica, é necessário ter cautela em relação ao desenvolvimento de tolerância, abstinência e interação medi- camentosa no uso crônico de cafeína. Unitermos: ANALGESIA; DOR; DROGAS, Alcaloide/cafeína. ©2012 Elsevier Editora Ltda. Todos os direitos reservados. INTRODUÇÃO Estrutura química A cafeína foi isolada em 1820, mas a estrutura correta des- A cafeína é um alcaloide presente em mais de 60 espécies ta metilxantina foi estabelecida na última década do século de plantas 4. Sua estrutura molecular pertence a um grupo XIX. Os efeitos não foram claramente reconhecidos até 1981, de xantinas trimetiladas que incluem seus compostos inti- quando o bloqueio de receptores adenosina foi correlacio- mamente relacionados: teobromina (presente no cacau) e nado às propriedades estimulantes da cafeína e de seus teofilina (presente no chá) 1. Quimicamente, esses alcaloides análogos 1. Provavelmente a cafeína é uma das substâncias são semelhantes a purinas, xantinas e ácido úrico, que são psicoativas mais utilizadas no mundo, promovendo efeitos compostos metabolicamente importantes 4. -

Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 BR 111 / 2017 The Minister responsible for health, in exercise of the power conferred by section 48A(1) of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979, makes the following Order: Citation 1 This Order may be cited as the Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017. Repeals and replaces the Third and Fourth Schedule of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 2 The Third and Fourth Schedules to the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 are repealed and replaced with— “THIRD SCHEDULE (Sections 25(6); 27(1))) DRUGS OBTAINABLE ONLY ON PRESCRIPTION EXCEPT WHERE SPECIFIED IN THE FOURTH SCHEDULE (PART I AND PART II) Note: The following annotations used in this Schedule have the following meanings: md (maximum dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered at any one time. 1 PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 mdd (maximum daily dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance that is contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered in any period of 24 hours. mg milligram ms (maximum strength) i.e. either or, if so specified, both of the following: (a) the maximum quantity of the substance by weight or volume that is contained in the dosage unit of a medicinal product; or (b) the maximum percentage of the substance contained in a medicinal product calculated in terms of w/w, w/v, v/w, or v/v, as appropriate.