Steve Brown's Bunyip and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One and Only

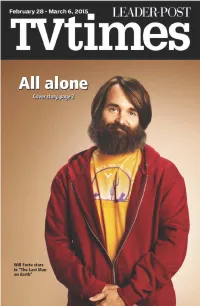

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Reflections on the Pinery Fire

Reflections on the Pinery fire 25 November 2015 Thank you Thank you very much to everyone who contributed material to this book, including written reflections, photographs, poems and art pieces. Due to space limitations it was not possible to include every submission. Copyright of each piece remains with the contributor. Language warning Some articles contain coarse language. This is noted at the beginning of the article. This book was compiled and edited by Nicole Hall, Project Officer, State Recovery Office on behalf of the Pinery Fire Community Action Group. Printed by Bunyip Print & Copy, Commercial Lane, Gawler with funding provided by State and Commonwealth Governments. 2 Contents Foreword.................................................. 4 All about people ....................................... 5 In memory ................................................ 6 HELL ON EARTH .................................... 7 Maps and statistics .................................. 8 Close calls, emotions and memories ..... 19 ROAD TO RECOVERY ......................... 41 Local Recovery Committee .................... 42 Volunteers.............................................. 44 Projects .................................................. 63 Community events ................................. 75 Good news and kind hearts ................... 84 Finance and fundraising ........................ 92 Impact .................................................... 98 One year on ......................................... 110 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..................... -

Gawler an Annotated Bibliography of Historical

GAWLER AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HISTORICAL, TECHNICAL AND SCIENTIFIC SOURCES IN SEVEN VOLUMES compiled by Phillip V. Thomas, M.A. Department of History University of Adelaide for The Corporation of the Town of Gawler VOLUME 4 Religion, Sport, Entertainment 1997 1 RELIGION, SPORT, ENTERTAINMENT (A) RELIGIOUS DENOMINATIONS, CHURCHES AND CHURCH BURIALS PRIMARY SOURCES British and Foreign Bible Society, Gawler Branch Annual Report of the Gawler Branch of the South Australian Auxiliary of the British and Foreign Bible Society . Published by the Branch (Adelaide, 1868). In this, the fourteenth report of the Gawler Branch, are the main report on numbers of Bibles sold, subscriptions and donations lists, balance sheet, and laws and regulations of the society. It is interesting to note that the President of the Branch is one Walter Duffield. Location: Mortlock Library Periodicals 206/B862a Gawler Methodist Church, Gawler Beacon: monthly newsletter of the Gawler Methodist Circuit (Gawler, 1961-1979). Continued by Beacon: Gawler Parish Magazine of the Uniting Church (Gawler, 1979-1987). Two boxes of unbound material relating to Methodist Church issues, news and views. Location: Mortlock Library Periodicals 287a Gawler Parish Magazine . W. Barnet, Printer (Gawler, 1948-1977). The Gawler Parish Magazine consists of parish notes and advertisements for: St. George's ChurchGawler, the Church of the Transfiguration, Gawler South and St. Michael and All Angels Church, Barossa. Location: Mortlock Library Periodicals 283.94232/G284 Hocking, Monica, St. George's Burial Records 1861-1886 . This is a copy from the book of the original curator, William Barrett. Handwritten records, with annotations for number of internment, burial plots, undertakers, names, year of death and place of residence. -

It Comes from the People: Community Development and Local Theology. REPORT NO ISBN-1-56639-212-8 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 408P.; Photographs May Not Reproduce Adequately

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 629 RC 026 443 AUTHOR Hinsdale, Mary Ann; And Others TITLE It Comes from the People: Community Development and Local Theology. REPORT NO ISBN-1-56639-212-8 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 408p.; Photographs may not reproduce adequately. AVAILABLE FROMTemple University Press, 1601 N. Broad St., USB-Room 305, Philadelphia, PA 19122 (clothbound, ISBN-I-56639-211-X; paperback, ISBN-1-56639-212-8). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Community Action; Community Development; *Community Education; *Community Leaders; *Consciousness Raising; Cultural Activities; *Females; Participatory Research; *Religious Factors; Rural Areas; Small Towns; Values IDENTIFIERS Bible Study; Community Renewal; Liberation Theology; Rituals; *Virginia (Ivanhoe) ABSTRACT The closing of local mines and factories collapsed the economic and social structure of Ivanhoe, Virginia, a small rural town once considered a dying community. This book is a case study that tells how the people of Ivanhoe organized to revitalize their town. It documents the community development process--a process that included hard work, a community consciousness raising experience that was intentionally sinsitive to cultural and religious values, and many conflicts. It tells the story.of the emergence and education of leaders, especially women, and the pain and joy of their growing and learning. Among these leaders is Maxine Waller,*a dominant, charismatic woman who gave the townspeople inspiration and a sense of their capabilities and of their rights as human beings. Part I covers the community development process and includes chapters on historical background, community mobilization, confrnnting and using power, community education, using culture in corlimuniLy development, leadership and organizational development, and the relationship between insiders and outsiders in participatory research. -

Cpage Paper 5 Marae Sept 30

2002 - 5 FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Media Ownership Working Group Program Diversity and the Program Selection Process on Broadcast Network Television By Mara Einstein September 2002 Executive Summary: This paper examines the extent to which program diversity has changed over time on prime time, broadcast network television. This issue is assessed using several different measurement techniques and concludes that while program diversity on prime time broadcast network television has fluctuated over time, it is not significantly different today than it was in 1966. The paper also explores the factors used by broadcast networks in recent years in program selection. It finds that networks’ program selection incentives have changed in recent years as networks were permitted to take ownership interests in programming. 2 A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON PROGRAM DIVERSITY Mara Einstein Department of Media Studies Queens College City University of New York The views expressed in this paper are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Communications Commission, any Commissioners, or other staff. 3 Introduction This paper analyzes the correlation between the FCC’s imposition of financial interest and syndication rules and program diversity on prime time broadcast network television. To demonstrate this, diversity will be examined in terms of 1) content diversity (types of programming) and 2) marketplace diversity (suppliers of programming). This analysis suggests that the structural regulation represented by the FCC’s financial interest and syndication rules have not been an effective means of achieving content diversity. Study Methodology By evaluating the content of programming over the periods surrounding the introduction and elimination of the financial interest and syndication rules, we will measure the trend in program diversity during the time when the financial interest and syndication (“fin-syn”) rules were in effect. -

Business Wire Catalog

Asia-Pacific Media Pan regional print and television media coverage in Asia. Includes full-text translations into simplified-PRC Chinese, traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean based on your English language news release. Additional translation services are available. Asia-Pacific Media Balonne Beacon Byron Shire News Clifton Courier Afghanistan Barossa & Light Herald Caboolture Herald Coast Community News News Services Barraba Gazette Caboolture News Coastal Leader Associated Press/Kabul Barrier Daily Truth Cairns Post Coastal Views American Samoa Baw Baw Shire & West Cairns Sun CoastCity Weekly Newspapers Gippsland Trader Caloundra Weekly Cockburn City Herald Samoa News Bay News of the Area Camden Haven Courier Cockburn Gazette Armenia Bay Post/Moruya Examiner Camden-Narellan Advertiser Coffs Coast Advocate Television Bayside Leader Campaspe News Collie Mail Shant TV Beaudesert Times Camperdown Chronicle Coly Point Observer Australia Bega District News Canberra City News Comment News Newspapers Bellarine Times Canning Times Condobolin Argus Albany Advertiser Benalla Ensign Canowindra News Coober Pedy Regional Times Albany Extra Bendigo Advertiser Canowindra Phoenix Cooktown Local News Albert & Logan News Bendigo Weekly Cape York News Cool Rambler Albury Wodonga News Weekly Berwick News Capricorn Coast Mirror Cooloola Advertiser Allora Advertiser Bharat Times Cassowary Coast Independent Coolum & North Shore News Ararat Advertiser Birdee News Coonamble Times Armadale Examiner Blacktown Advocate Casterton News Cooroy Rag Auburn Review -

Gawler-Bib-Vol-6.Pdf

GAWLER AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HISTORICAL, TECHNICAL AND SCIENTIFIC SOURCES IN SEVEN VOLUMES compiled by Phillip V. Thomas, M.A. Department of History University of Adelaide for The Corporation of the Town of Gawler VOLUME 6 Local Government Issues: Development , Community Conditions, Infrastructure and Heritage 1997 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ISSUES: DEVELOPMENT, COMMUNITY CONDITIONS, INFRASTRUCTURE AND HERITAGE (A) BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Adelaide Region (Excluding the metropolitan Area) South Australia Present and Future Development . Commonwealth Bank (Adelaide?, 1952). Gawler is reviewed on pp. 28-29 of this study which analysed the possibilities of metropolitan development after World War Two. In 1947 Gawler's population was 4,450. Prospects for development, district industries, rainfall, livelihood and the town's relation to other centres are discussed briefly. Location: Gawler Public Library LH/TP/21 Note : A near-identical report for the Light Region, north of Gawler, was undertaken by the Commonwealth Bank Research Department in 1951. A copy of this is located at the Gawler Public Library LH/TP/22. "Blueprint for town of 50,000", The Bunyip , 1 November (1995), pp. 1, 2. Phil Sarin, Environment and Planning Services Manager, promotes the strategic plan on business and residential development prepared for the Gawler Town Council by Rust PPK Pty. Ltd. The article includes two maps. One is the overall strategy plan, the other is the access and transport plan. Location: Northern Suburbs Family Resource Centre The Bunyip Scrapbook Note : See the entry for Rust PPL Pty. Ltd.'s publication. Corporation of the Town of Gawler, Community Information Directory/Business and Information Directory . Corporation of the Town of Gawler (Gawler, 1981-1994). -

Book 1 26, 27 and 28 February 2002

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 1 26, 27 and 28 February 2002 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Health............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education Services and Minister for Youth Affairs......... The Hon. M. M. Gould, MLC Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Energy and Resources and Minister for Ports.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Minister for State and Regional Development, Treasurer and Minister for Innovation........................................ The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Workcover............ The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Senior Victorians and Minister for Consumer Affairs....... The Hon. C. M. Campbell, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Environment and Conservation.......................... The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections........................................ The Hon. A. Haermeyer, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs............ The Hon. K. G. Hamilton, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Manufacturing Industry and Minister for Racing............................................ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Minister for Education and Training................................ The Hon. L. J. Kosky, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Industrial Relations.............. The Hon. J. J. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Queensland eSpace AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 36 February 2006 Compiled for the ANHG by Rod Kirkpatrick, 13 Sumac Street, Middle Park, Qld, 4074. Ph. 07-3279 2279. E-mail: [email protected] 36.1 COPY DEADLINE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for next Newsletter: 30 April 2006. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the “Publications” link of the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/journ-comm/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://eprint.uq.edu.au/) CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: METROPOLITAN 36.2 DEATH OF KERRY PACKER Kerry Francis Bullmore Packer died in his sleep on 26 December 2005, aged 68. Packer, who was Australia’s wealthiest citizen, was a sometime newspaper owner (mainly regional newspapers, but also the Canberra Times, 1987-89), and the principal shareholder in Publishing & Broadcasting Ltd (PBL), which runs, amongst other enterprises, the biggest stable of magazines in Australia and the Nine television network. He was the third-generation member of the Packer media dynasty. His father, Sir Frank Packer, owned the Daily Telegraph from 1936-72 and started Channel 9 in both Sydney and Melbourne; and Kerry’s grandfather, Robert Clyde Packer, was a newspaper manager and owner whose fortunes received a wonderful boost when he was given a one-third interest in Smith’s Weekly. On 28 December and on succeeding days, Australian newspapers gave extensive coverage to the death of Kerry Packer and its implications for the future of PBL, but especially the Nine Network. -

CBC's Hit Original Drama Coroner Begins Production on Season 4

CBC’s hit original drama Coroner begins production on Season 4 July 27, 2021 Greg David From a media release: Muse Entertainment, Cineflix Studios, and Back Alley Films are thrilled to announce that production has started in Toronto and Ontario on season four (12×60) of the CBC original series and audience favourite CORONER, starring Serinda Swan (Inhumans, Ballers) as coroner Dr. Jenny Cooper with Roger Cross (Dark Matter, Caught) as Detective Donovan McAvoy. Inspired by the best-selling series of books by M.R. Hall and created for television by Morwyn Brebner (Saving Hope, Rookie Blue), the new season will debut on CBC and the CBC Gem streaming service in Winter 2022. This season, Serinda Swan will feature her talents behind the camera for her television series directorial debut. Swan joins a dynamic and acclaimed group of directors including Adrienne Mitchell (Durham County, Bellevue), Ruba Nadda (Frankie Drake Mysteries), Farhad Mann (Murdoch Mysteries), Samir Rehem (Tiny Pretty Things), Cory Bowles (Pretty Hard Cases) and Liz Farrer (Coroner). Award-winning writer/producer Adriana Maggs (Caught, Grown Up Movie Star) will lead the series as Showrunner with a celebrated and illustrious writing team including Noelle Carbone (Wynonna Earp), Shannon Masters (Cardinal), Laura Good (Burden of Truth), Nathalie Younglai (Super Zee), Seneca Aaron (Nurses), Wendy ‘Motion’ Brathwaite (Akilla’s Escape), JP Larocque (Another Life), Mazi Khalighi (Foraldraskap) and Lindsey Addawoo (Promise Me). CORONER stars Serinda Swan as Dr. Jenny Cooper with Roger Cross as Detective Donovan McAvoy; Ehren Kassam (Degrassi, Next Class) as Ross; Nicholas Campbell (Da Vinci’s Inquest, Bad Blood) as Gordon Cooper; Jennifer Dale (SurrealEstate) as Margaret ‘Peggy’; Andy McQueen (Station Eleven) as Malik Abed; Kiley May (It Chapter Two) as River Baitz; Shawn Ahmed (Awake) as Alphonse; and Jon de Leon (Downsizing) as Dennis Garcia. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

The offices of the Bunyip, Gawler, South Australia, on 29 January 2003 when the ANHG editor visited to interview editor John Barnet and brother Craig. The Barnets, who had owned the paper since helping to found it in 1863, sold the paper on 31 March 2003 to the Taylor family, of the Murray Pioneer, Renmark. The Bunyip celebrated its 150th anniversary on 5 September this year. It began as a monthly satirical journal under the title of the Bunyip; or Gawler Humbug Society’s Chronicle, Flam! Bam!! Sham!!! It omitted the Humbug Society guff from its title in 1864, appeared twice a month in 1865 and weekly from 1866. William Barnet, the founding printer and owner, died in 1895. The Barnets’ possible sale of the Bunyip had been discussed since soon after the death of third-generation owner Kenneth Lindley Barnet on 16 May 2000. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 74 October 2013 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, PO Box 8294 Mount Pleasant Qld 4740. Ph. +61-7-4942 7005. Email: [email protected]/ Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra. Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 9 December 2013. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. A composite index of issues 1 to 75 of ANHG is being prepared.