It Comes from the People: Community Development and Local Theology. REPORT NO ISBN-1-56639-212-8 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 408P.; Photographs May Not Reproduce Adequately

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

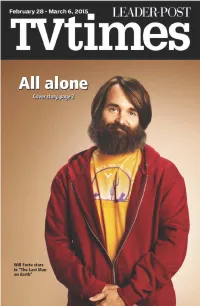

One and Only

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

Leedstown.Lwp

Leedstown and Fincastle Jim Glanville Copyright 2010 All rights reserved Blue links in the footnotes are clickable The Winter 2010 Newsletter of the Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Society announced a February 27th, 2010 reenactment of the 243rd anniversary of the Leedstown Resolutions1 saying: "History will come to life along the streets of Tappahannock as NNVHS and the Essex County Museum and Historical Society combine to present dramatic reenactments of the famous 1766 Tappahannock Demonstrations to enforce the Leedstown Resolutions, against the wealthy and insolent Archibald Ritchie2 and the Scotsman Stamp Collector, Archibald McCall, who was tarred and feathered for his refusal to comply." Because I am interested in, and have written about, the pre-revolutionary-period Virginia County Resolutions I decided to attend. This article tells about the 1766 Leedstown Resolutions (adopted in Westmoreland County) and their February 2010 reenactment in Tappahannock. It also tells about the role of Richard Henry Lee during the buildup to revolution in Virginia and explores the connections between Westmoreland County and Fincastle County, which existed briefly from 1772-1776. Reenacting an event of 244 years earlier, Richard Henry Lee Richard Henry Lee confronts Archibald McCall (portrayed (portrayed by Ted Borek) acting on behalf of the Westmoreland by Dan McMahon) and his wife (portrayed by Judith Association confronts Archibald Ritchie (portrayed by Bob Bailey) Harris) on the steps of the extensively restored at Ritchie's front door in Tappahannock. Samuel Washington Brockenbrough-McCall House4 that is today a part of (portrayed by John Harris) stands with a cane. Bailey as Ritchie present day St. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third and last installment of the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans, to be republished in JBS. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement BY RICHARD OSBORN Patriot (1775-1778) Revolutions ultimately conclude with a large scale resolution in the major political, social, and economic issues raised by the upheaval. During the final two years of the American Revolution, William Preston struggled to anticipate and participate in the emerging American regime. For Preston, the American Revolution involved two challenges--Indians and Loyalists. The outcome of his struggles with both groups would help determine the results of the Revolution in Virginia. If Preston could keep the various Indian tribes subdued with minimal help from the rest of Virginia, then more Virginians would be free to join the American armies fighting the English. But if he was unsuccessful, Virginia would have to divert resources and manpower away from the broader colonial effort to its own protection. The other challenge represented an internal one. A large number of Loyalist neighbors continually tested Preston's abilities to forge a unified government on the frontier which could, in turn, challenge the Indians effectivel y and the British, if they brought the war to Virginia. In these struggles, he even had to prove he was a Patriot. Preston clearly placed his allegiance with the revolutionary movement when he joined with other freeholders from Fincastle County on January 20, 1775 to organize their local county committee in response to requests by the Continental Congress that such committees be established. -

William Campbell of King's Mountain David George Malgee

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 8-1983 A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain David George Malgee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Malgee, David George, "A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain" (1983). Master's Theses. 1296. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses/1296 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain by David George Malgee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Richmond In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in History August, 1983 A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the Graduate School of the University of Richmond by David George Malgee Approved: Introduction . l Chapter I: The Early Years ........................................ 3 Chapter II: Captain Campbell ...................................... 22 Chapter III: The Outbreak of the American Revolution .............. 39 Chapter IV: The Quiet Years, 1777 - 1778 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 56 Chapter V: The Critical Months, April 1779 - June 1780 ............ 75 Chapter VI: Prelude to Fame . 97 Chapter VII: William Campbell of King's Mountain .................. 119 Chapter VIII: Between Campaigns, November - December 1780 ......... 179 Chapter IX: The Guilford Courthouse Campaign ...................... 196 Chapter X: General William Campbell, April - August 1781 ......... -

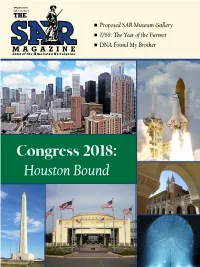

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Love & Wedding

651 LOVE & WEDDING THE O’NEILL PLANNING RODGERS BROTHERS – THE MUSIC & ROMANCE A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR YOUR WEDDING 35 songs, including: All at PIANO MUSIC FOR Book/CD Pack Once You Love Her • Do YOUR WEDDING DAY Cherry Lane Music I Love You Because You’re Book/CD Pack The difference between a Beautiful? • Hello, Young Minnesota brothers Tim & good wedding and a great Lovers • If I Loved You • Ryan O’Neill have made a wedding is the music. With Isn’t It Romantic? • My Funny name for themselves playing this informative book and Valentine • My Romance • together on two pianos. accompanying CD, you can People Will Say We’re in Love They’ve sold nearly a million copies of their 16 CDs, confidently select classical music for your wedding • We Kiss in a Shadow • With a Song in My Heart • performed for President Bush and provided music ceremony regardless of your musical background. Younger Than Springtime • and more. for the NBC, ESPN and HBO networks. This superb The book includes piano solo arrangements of each ______00313089 P/V/G...............................$16.99 songbook/CD pack features their original recordings piece, as well as great tips and tricks for planning the of 16 preludes, processionals, recessionals and music for your entire wedding day. The CD includes ROMANCE: ceremony and reception songs, plus intermediate to complete performances of each piece, so even if BOLEROS advanced piano solo arrangements for each. Includes: you’re not familiar with the titles, you can recognize FAVORITOS Air on the G String • Ave Maria • Canon in D • Jesu, your favorites with just one listen! The book is 48 songs in Spanish, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Ode to Joy • The Way You divided into selections for preludes, processionals, including: Adoro • Always Look Tonight • The Wedding Song • and more, with interludes, recessionals and postludes, and contains in My Heart • Bésame bios and photos of the O’Neill Brothers. -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

Fiction Fix 04 Melissa Milburn

University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons Fiction Fix Department of English Fall 2005 Fiction Fix 04 Melissa Milburn Sarah Clarke-Stuart Kristen Iannuzzi Vanessa Wells Nathan Holic See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/fiction_fix Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Suggested Citation Last, First. "Article Title." Fiction Fix 4 (2005): pages. Web. Date accessed. http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/fiction_fix/13 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fiction Fix by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © Fall 2005 All Rights Reserved Authors Melissa Milburn, Sarah Clarke-Stuart, Kristen Iannuzzi, Vanessa Wells, Nathan Holic, Joshua Kreis McTiernan, Ron Perline, Tina Helvie, Gavin Lambert, Jamie Hughes, Tim Gilmore, and April Fisher This book is available at UNF Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/fiction_fix/13 ® ~ ~ rrll\\®c~Ullil~rru choice award ~rr o ~U®D1l o~D1lD1lM~o W~01l®~~~ W®~~~ D1l~Ulh1~D1l lfu©~O@ ]©~lh1M~ ll\\rr®o~ mm@Uo®rrD1l~D1l ( [j'@[]1) [p)®rt'~001l® Uo01l~ lfu®~WO® ®~woD1l ~~mmlQJ®rru ]~mmo® lh1M@lh1®~ uomm ®o~mm©rr® ~[p)rro~ lfo~lfu®rr reader's choice award fourth inject ioll.\'Oillllll' 1\'.Ldl :2l)()=j I.:I 'OII~AUOS>fJD f X!.:f UO~.J.J~.:f 9002 U!JdS AI wn1oA X! ! !.:1 Copyright © 2006 by Fiction Fix All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Original Purchase Was Blood, and Mine Shall Seal the Surrender”: the Importance of Place in Botetourt County’S Resolutions, 1775

“The original purchase was blood, and mine shall seal the surrender”: The Importance of Place in Botetourt County’s Resolutions, 1775 Sarah E. McCartney On March 11, 1775, the Virginia Gazette published a statement of support and instruction from the freeholders of Botetourt County to their delegates at the upcoming Second Virginia Convention, scheduled to begin just nine days later.1 The Second Virginia Convention, held at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, is best remembered as the place of Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech; however, Henry’s passionate address and statement that he had “but one lamp by which my feet are guided; and that is the lamp of experience” were not the first stirring sentiments or emphasis on history and experience expressed in Virginia in 1775.2 Through the winter months of 1775, four counties—Augusta, Botetourt, Fincastle, and Pittsylvania—which were part of Virginia’s frontier region known as the “backcountry” and spanned the Shenandoah Valley and Allegheny Mountains, published resolutions articulating their agreement with the growing patriotic fervor.3 These resolutions also gave instructions to county delegates and Virginia’s patriot leaders to champion the revolutionary cause. This article specifically considers the resolutions from Botetourt County and situates those resolutions within the context of the region’s settlement history and experience, arguing for the importance of place as a foundational element of revolutionary-era sentiment in a frontier region where historians often focus on movement and impermanence. The Botetourt Resolutions Resolutions from Fincastle County, Botetourt County’s neighbor, were the first in a wave of statements issued by Virginia’s western counties through the winter months of 1775, and they have received substantial attention from historians;4 however, the Botetourt Resolutions (see Appendix) are less well known despite similar language and a compelling portrait of backcountry hardships and experience. -

An Examination of Contemporary Christian Music Success Within Mainstream Rock and Country Billboard Charts Megan Marie Carlan

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 8-21-2019 An Examination of Contemporary Christian Music Success Within Mainstream Rock and Country Billboard Charts Megan Marie Carlan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Music Business Commons An Examination of Contemporary Christian Music Success Within Mainstream Rock and Country Billboard Charts By Megan Marie Carlan Arts and Entertainment Management Dr. Theresa Lant Lubin School of Business August 21, 2019 Abstract Ranging from inspirational songs void of theological language to worship music imbued with overt religious messages, Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) has a long history of being ill-defined. Due to the genre’s flexible nature, many Christian artists over the years have used vague imagery and secular lyrical content to find favor among mainstream outlets. This study examined the most recent ten-year period of CCM to determine its ability to cross over into the mainstream music scene, while also assessing the impact of its lyrical content and genre on the probability of reaching such mainstream success. For the years 2008-2018, Billboard data were collected for every Christian song on the Hot 100, Hot Rock Songs, or Hot Country Songs in order to detect any noticeable trend regarding the rise or fall of CCM; each song then was coded for theological language. No obvious trend emerged regarding the mainstream success of CCM as a whole, but the genre of Rock was found to possess the greatest degree of mainstream success. Rock also, however, was shown to have a very low tolerance for theological language, contrasted with the high tolerance of Country. -

Cpage Paper 5 Marae Sept 30

2002 - 5 FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Media Ownership Working Group Program Diversity and the Program Selection Process on Broadcast Network Television By Mara Einstein September 2002 Executive Summary: This paper examines the extent to which program diversity has changed over time on prime time, broadcast network television. This issue is assessed using several different measurement techniques and concludes that while program diversity on prime time broadcast network television has fluctuated over time, it is not significantly different today than it was in 1966. The paper also explores the factors used by broadcast networks in recent years in program selection. It finds that networks’ program selection incentives have changed in recent years as networks were permitted to take ownership interests in programming. 2 A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON PROGRAM DIVERSITY Mara Einstein Department of Media Studies Queens College City University of New York The views expressed in this paper are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Communications Commission, any Commissioners, or other staff. 3 Introduction This paper analyzes the correlation between the FCC’s imposition of financial interest and syndication rules and program diversity on prime time broadcast network television. To demonstrate this, diversity will be examined in terms of 1) content diversity (types of programming) and 2) marketplace diversity (suppliers of programming). This analysis suggests that the structural regulation represented by the FCC’s financial interest and syndication rules have not been an effective means of achieving content diversity. Study Methodology By evaluating the content of programming over the periods surrounding the introduction and elimination of the financial interest and syndication rules, we will measure the trend in program diversity during the time when the financial interest and syndication (“fin-syn”) rules were in effect.