Defining the Big Thicket: Prelude to Preservation James Cozine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The TEXAS ARCHITECT INDEX

Off1cial Publication of the TEXAS ARCHITECT The Texas Society of ArchitiiCU TSA IS the off•cu11 organization of the Texas VOLUME 22 / MAY, 1972 / NO. 5 Reg•on of the Amer1c:an lnst1tut10n of Archllecu James D Pfluger, AlA Ed1t0r Taber Ward Managmg Ed110r Banny L Can1zaro Associate Eduor V. Raymond Smith, Al A Associate Ed1tor THE TEXAS ARCH ITECT " published INDEX monthly by Texas Society of Architects, 904 Perry Brooks Buildtng, 121 East 8th Street, COVER AND PAGE 3 Austen, Texas 78701 Second class postage pa1d at Ausun, Texas Application to matl at Harwood K. Sm 1th and Partners second clan postage rates Is pend1ng ot Aunen, Texas. Copynghtcd 1972 by the TSA were commissioned to design a Subscription price, $3.00 per year, In junior college complex w1th odvuncc. initial enrollment of 2500 Edllonal contnbut1ons, correspondence. and students. The 245-acre site w1ll advertising material env1ted by the editor Due to the nature of th publlcauon. editorial ultimately handle 10,000 full-time conuulbullons cannot be purchoscd students. Pub11sher g•ves p rm1ss on for reproduction of all or part of edatonal matenal herem, and rcQulllts publication crcd1t be IJIVCn THE PAGE 6 TEXAS ARCHITECT, and Dllthor of matenol when lnd•C3ted PubiJcat•ons wh1ch normally The Big Thicket - a wilderness pay for editon I matenal are requested to grvc under assault. Texans must ac conStdcrat on to the author of reproduced byhned feature matenal cept the challenge of its surv1val. ADVERTISERS p 13 - Texas/Unicon Appearance of names and p1ctures of products and services m tither ed1torlal or PAGE 11 Structures. -

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas Texans Outdoors: An Analysis of 1985 Participation in Outdoor Recreation Activities By Kathryn N. Nichols and Andrew P. Goldbloom Under the Direction of James A. Deloney November, 1989 Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, Texas 78744 (512) 389-4900 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Conducting a mail survey requires accuracy and timeliness in every single task. Each individualized survey had to be accounted for, both going out and coming back. Each mailing had to meet a strict deadline. The authors are indebted to all the people who worked on this project. The staff of the Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division, deserve special thanks. This dedicated crew signed letters, mailed, remailed, coded, and entered the data of a twenty-page questionnaire that was sent to over twenty-five thousand Texans with over twelve thousand returned completed. Many other Parks Division staff outside the branch volunteered to assist with stuffing and labeling thousands of envelopes as deadlines drew near. We thank the staff of the Information Services Section for their cooperation in providing individualized letters and labels for survey mailings. We also appreciate the dedication of the staff in the mailroom for processing up wards of seventy-five thousand pieces of mail. Lastly, we thank the staff in the print shop for their courteous assistance in reproducing the various documents. Although the above are gratefully acknowledged, they are absolved from any responsibility for any errors or omissions that may have occurred. ii TEXANS OUTDOORS: AN ANALYSIS OF 1985 PARTICIPATION IN OUTDOOR RECREATION ACTIVITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................... -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District ANDERSON 396 - XXX D PALESTINE PICNIC AND CAMPING PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $136,086.77 C 8/23/1976 3/1/1979 2 719 - XXX D COMMUNITY FOREST PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $275,500.00 C 8/23/1979 8/31/1985 2 ANDERSON County Total: $411,586.77 County Count: 2 ANDREWS 931 - XXX D ANDREWS MUNICIPAL POOL CITY OF ANDREWS $237,711.00 C 12/6/1984 12/1/1989 19 ANDREWS County Total: $237,711.00 County Count: 1 ANGELINA 19 - XXX C DIBOLL CITY PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $174,500.00 C 10/7/1967 10/1/1971 2 215 - XXX A COUSINS LAND PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $113,406.73 C 8/4/1972 6/1/1973 2 297 - XXX D LUFKIN PARKS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $49,945.00 C 11/29/1973 1/1/1977 2 512 - XXX D MORRIS FRANK PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $236,249.00 C 5/20/1977 1/1/1980 2 669 - XXX D OLD ORCHARD PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $235,066.00 C 12/5/1978 12/15/1983 2 770 - XXX D LUFKIN TENNIS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $51,211.42 C 6/30/1980 6/1/1985 2 879 - XXX D HUNTINGTON CITY PARK CITY OF HUNTINGTON $35,313.56 C 9/26/1983 9/1/1988 2 ANGELINA County Total: $895,691.71 County Count: 7 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 2 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. -

National Forests & Grasslands in Texas

Cooperative Wildlife Management Areas Designated trails (in miles) (USFS/Texas Parks and Wildlife Department) Multi-use Angelina National Forest Ranger Multi-use Mountain NATIONAL FORESTS & Hiking non- District Motorized Bike Bannister 25,658 acres motorized Davy Crockett National Forest Angelina 2.7 GRASSLANDS IN TEXAS Davy Alabama Creek 14,561 acres Crockett 22 52 Sabine National Forest FINGERTIP FACTS Sabine 1 Moore Plantation 26,455 acres FOREST SUPERVISOR – Eddie Taylor Sam Houston 120 85 20 Caddo National Grassland Caddo/LBJ 0 92 4 Caddo 16,150 acres TOTALS 147.7 144 85 24 Sam Houston National Forest THE ORGANIZATION: Four National Forests and two National Grasslands comprising 675,816 Sam Houston 162,984 acres acres in 15 counties make up the National Minerals Forests & Grasslands in Texas. Forest Supervisor Permitted wells 299 Wilderness Areas Headquarters is in Lufkin. Approximately 140 Reserved/Outstanding Mineral Acres 203,339 Angelina National Forest employees make up the workforce. 2000 Soil Resource Inventory – Order II: 675,832 acres completed. Turkey Hill 5,473 acres This completes the Order II update for the NFGT. Upland Island 13,331acres Angelina National Forest Established in 1934 Davy Crockett National Forest Ranger District Office in Zavalla Designated miles of roads Big Slough 3,639 acres Acres: 153,334 State County USFS Sabine National Forest Acres per county: Angelina, 58,684; Jasper, 21,023; San Augustine, 64,389; Nacogdoches, 9,238 1,836 1,598 2,394 Indian Mounds 12,369acres Davy Crockett National Forest Sam Houston National Forest Established 1934 Ongoing research projects Little Lake Creek 3,855 acres Ranger District Office in Ratcliff Wildlife (8) & Fisheries (2) 10 Botanical 3 Acres: 160,467 Silvicultural 1 Insects 1 Acres per county: Houston, 93,155; Trinity, 67,312 Archeology 2 Chemical 0 Long-term Soil Productivity 1 TOTAL 18 Sabine National Forest Established 1934 Grazing – 5,000 AUMs graze on 17,438 acres. -

Big Thicket Reporter, Issue

BIG THICKET October-November-December 2013 Reporter Issue #120 BIG THICKET DAY, October 12 Big Thicket Day 2013 began with ences. She provided a litany of his a board and membership meeting achievements, including his 18-year with Jan Ruppel, President, presiding. summer workshops for Environ- mental Science Teachers, his publi- The keynote speaker was Dr. Ken cations, research, awards, and other Kramer, former Executive Direc- awards received and offi ces held. tor of the Lone Star Chapter, Sierra Club and current volunteer Water Mona Halvorsen reported on the Resources Chair and Legislative Thicket of Diversity, All Taxa Biodiversity Advisor, who addressed “Our State’s Inventory. (See Diversity Dispatch). Water Future – Progress and Chal- lenges.” Kramer noted that the Leg- Michael Hoke, Chair of the Neches islature made signifi cant eff orts this River Adventures Committee, pre- year to advance water conserva- sented a PowerPoint that included tion and to fi nance infrastructure, plans for curricula-based student use. and he outlined challenges ahead. Dr. Ken Kramer was the keynote Dr. James Westgate gave the elec- speaker for Big Thicket Day Ann Roberts, Chair of the Awards tion report for the Nominating Committee, presented the R.E. Committee. All nominees were After lunch, committees met to work Jackson Conservation Award to Dr. elected including Betty Grimes as on upcoming plans and projects. James Westgate, Lamar University Secretary plus two new directors — Professor of Earth and Space Sci- Leslie Dubey and Iolinda Gonzalez. Presidential Footnotes … By Jan Ruppel Because of the government shut- have a number of activities devel- the preservation and protection of down we held BTA’s 49th Big Thicket oping to celebrate throughout the the Big Thicket region and continue Day at First Baptist Church in Sara- year. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

GOOSE ISLAND STATE PARK STATE ISLAND GOOSE Concession Building

PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Born out of the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps put young men to work in the 1930s. The jobs involved building parks and conserving natural resources across the country. Many of our state parks here in Texas display the CCC’s handiwork. Texas now has 29 CCC state parks. Some, like Garner and Palo Duro Canyon, are well known to travelers across the state. So here’s a list of some CCC parks you may not have visited … yet. By Dale Blasingame � PHOTO BY EARL NOTTINGHAM / TPWD PHOTO © LAURENCEPHOTO PARENT ABILENE STATE PARK PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Map and directions CCC enrollees used native limestone and 150 Park Road 32 red sandstone to build many of the park’s Tuscola, TX 79562 features, including the arched concession building (with observation tower) and the Latitude: 32.240731 water tower. The CCC also constructed the Longitude: -99.879139 swimming pool, with pyramidal poolside pergolas. Online reservations (325) 572-3204 Entrance Fees Adult Day Use: $5 Daily Child 12 and Under: Free Visit park website PHOTO BY TPWD BY PHOTO BONHAM STATE PARK PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Map and directions The CCC touch can be seen everywhere – 1363 State Park 24 from the earthen dam used to form the Bonham, TX 75418 65-acre lake to the boathouse and park headquarters. Visit the CCC-constructed Latitude: 33.546727 picnic area first, which houses my favorite Longitude: -96.144758 footbridge in all of Texas. Online reservations (903) 583-5022 Entrance Fees Adult Day Use: $4 Daily Child 12 and Under: Free Visit park website PHOTO BY CHASE FOUNTAIN / TPWD CHASE BY PHOTO FOUNTAIN � MORE � DAVIS MOUNTAINS STATE PARK PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Map and directions Indian Lodge, the pueblo-style hotel in PO Box 1707 Davis Mountains State Park, reflects the Fort Davis, TX 79734 history and culture of the region. -

(USDA) Forest Service Working with Partners for Bird Conservation

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service Appendix A Working with Partners for Bird Conservation Bird Conservation Accomplishments Published 2004 This appendix lists the bird conservation accomplishment projects by USDA Forest Service Deputy Areas: National Forest Systems, Research and Development, State and Private and International Programs. This is not a complete set of the many bird conservation actions that have been or are currently being implemented across Forest Service Deputy Areas. It represents bird conservation accomplishment projects from the administrative units that replied at the time of the request. Projects started before fiscal year 2000 that are ongoing or conducted annually (beyond 2002) are reported as “ongoing” or “annually”, with the date of inception included (when known). I. National Forest Systems Region 1 (R-1): Northern Region Regionwide Accomplishments Partnership Enhancement • Partners in Flight (PIF) and Bird Conservation Region (BCR) Plans. Forest Service biologists throughout the Northern Region participated in the development of PIF and BCR plans for Montana, Idaho, North Dakota, and South Dakota. Active participation is ongoing with PIF working groups, BCR coordinators, joint venture meetings, and other activities that promote bird conservation. Partners in these efforts include the American Bird Conservancy (ABC), Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks (MFWP), Idaho Department of Fish and Game 1 (Idaho Fish & Game), U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Potlatch Corp., Plum Creek Timber Co., local Audubon Society Chapters, and the Universities of Montana and Idaho. Ongoing since FY1993. • Montana Sage Grouse and Sagebrush Conservation Strategy. The Northern Region participated in the Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks-led effort to develop a statewide sage grouse and sagebrush conservation strategy. -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

PWD MP P4506-001Fabilene.Ai

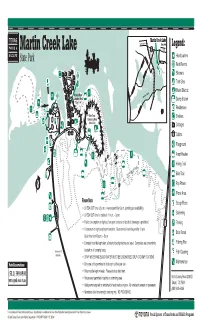

Martin Creek Lake To Henderson State Park Legend: 43 To Tatum Martin Creek Lake TEXAS FM 2144 Headquarters State Park CR 2183 Rest Rooms FM 2148 8 11 10 9 Power Showers 7 FM 2658 Plant 12 6 Tent Sites 13 5 14 4 FM 1251 Water/Electric 15 FM 2658 Broken Bowl k 16 Martin Cree Camping Area 55 54 56 53 Dump Station 17 52 Sites 1-34 57 18 34 51 3 33 32 31 66 67 Residences 19 58 65 68 69 50 22 30 70 FM 3231 20 2 23 64 24 Bee Tree 49 Shelters 59 Camping Area 71 1 25 21 29 Sites 35-81 72 48 60 63 2 47 Cottages 26 28 62 73 61 46 1 2 27 74 45 1 Cabins 81 75 80 35 76 44 36 37 79 Playground 38 78 77 39 43 42 Amphitheater 40 41 Hiking Trail Old Henderson Road Bike Trail Pay Phone Picnic Area Please Note: Group Picnic • CHECK OUT time is 2 p.m. or renew permit by 9 a.m. (pending site availability). • CHECK OUT time for cabins is 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Swimming 43 • Public consumption or display of an open container of alcoholic beverage is prohibited. TEXAS Parking • A maximum of eight people per campsite. Guests must leave the park by 10 p.m. Boat Ramp Quiet time from 10 p.m. – 6 a.m. • Campsite must be kept clean; all trash picked up before you leave. Dumpsters are conveniently Fishing Pier Harmony Hill located on all camping loops. -

Sustaining Our State's Diverse Fish and Wildlife Resources: Conservation Delivery Through the Recovering America's Wildl

Sustaining Our State’s Diverse Fish and Wildlife Resources Conservation delivery through the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act 2019 This report and recommendations were prepared by the TPWD Texas Alliance for America’s Fish and Wildlife Task Force, comprised of the following members: Tim Birdsong (TPWD Inland Fisheries Division) Greg Creacy (TPWD State Parks Division) John Davis (TPWD Wildlife Division) Kevin Davis (TPWD Law Enforcement Division) Dakus Geeslin (TPWD Coastal Fisheries Division) Tom Harvey (TPWD Communications Division) Richard Heilbrun (TPWD Wildlife Division) Chris Mace (TPWD Coastal Fisheries Division) Ross Melinchuk (TPWD Executive Office) Michael Mitchell (TPWD Law Enforcement Division) Shelly Plante (TPWD Communications Division) Johnnie Smith (TPWD Communications Division) Acknowledgements: The TPWD Texas Alliance for America’s Fish and Wildlife Task Force would like to express gratitude to Kim Milburn, Larry Sieck, Olivia Schmidt, and Jeannie Muñoz for their valuable support roles during the development of this report. CONTENTS 1 The Opportunity Background 2 The Rich Resources of Texas 3 The People of Texas 4 Sustaining Healthy Water and Ecosystems Law Enforcement 5 Outdoor Recreation 6 TPWD Allocation Strategy 16 Call to Action 17 Appendix 1: List of Potential Conservation Partners The Opportunity Background Passage of the Recovering America's Our natural resources face many challeng- our lands and waters. The growing num- Wildlife Act would mean more than $63 es in the years ahead. As more and more ber of Texans seeking outdoor experiences million in new dollars each year for Texas, Texans reside in urban areas, many are will call for new recreational opportunities. transforming efforts to conserve and re- becoming increasingly detached from any Emerging and expanding energy technol- store more than 1,300 nongame fish and meaningful connection to nature or the ogies will require us to balance new en- wildlife species of concern here in the outdoors. -

State No. Description Size in Cm Date Location

Maps State No. Description Size in cm Date Location National Forests in Alabama. Washington: ALABAMA AL-1 49x28 1989 Map Case US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service. Bankhead National Forest (Bankhead and Alabama AL-2 66x59 1981 Map Case Blackwater Districts). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Coronado National Forest (Nogales A: 67x72 ARIZONA AZ-1 1984 Map Case Ranger District). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B: 67x63 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Sierra Vista Ranger District). Side A : Coconino National Forest (North A:69x88 Arizona AZ-2 1976 Map Case Half). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:69x92 Side B : Coconino National Forest (South Half). Side A : Coronado National Forest (Sierra A:67x72 Arizona AZ-3 1976 Map Case Vista Ranger District. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:67x72 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Nogales Ranger District). Prescott National Forest. Washington: US Arizona AZ-4 28x28 1992 Map Case Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Kaibab National Forest (North Unit). Arizona AZ-5 68x97 1967 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Prescott National Forest- Granite Mountain Arizona AZ-6 67x48.5 1993 Map Case Wilderness. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Prescott National Forest (East Half). A:111x75 Arizona AZ-7 1993 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:111x75 Side B : Prescott National Forest (West Half). Arizona AZ-8 Superstition Wilderness: Tonto National 55.5x78.5 1994 Map Case Forest. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Arizona AZ-9 Kaibab National Forest, Gila and Salt River 80x96 1994 Map Case Meridian.