From the Douro Valley to Oporto Cellars: the Port Wine Value Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belo Portugal: Wine, History and Landscapes Along the Douro River

How To Register: Participants must first pre-register with New York State United Teachers Retiree Council 10. Pricing includes $50 registration fee for members having paid RC10 sustaining membership fee. Guests and members not having paid the sustaining membership Belo Portugal: Wine, History and fee, add $50. To pre-register, contact Karen Maher by phone at (518) 477-6746 or via email at [email protected]. Landscapes Along the Douro River To enroll in this adventure, please call Road Scholar toll free at (800) 322-5315 and reference Program #15893, “Belo Portugal: An Exclusive Learning Adventure for Wine, History and Landscapes Along the Douro River,” starting Sept. 2, 2017 and say that you are a member of New York State New York State United Teachers Retiree Council 10 United Teachers Retiree Council 10. SEPT. 2–14, 2017 Program Price: • Category 1: DBL $3,695 Upper-deck cabin with 2 twin beds convertible to 1 double bed; 129 sq. ft. • Category 2: DBL $3,595 | SGL $4,195 Middle-deck cabin with 2 twin beds convertible to 1 double bed; 129 sq. ft. Roommate matching available in this category. • Category 3: DBL $3,395 Main Deck Cabin with 2 twin beds convertible to 1 double bed; 129 sq. ft. Payment/Cancellation Schedule: Should you need to cancel from this program, please refer to the chart below for schedule and refund information. Payment Schedule Deposit Payment $500 (due upon enrollment) Final payment due May 25, 2017 Cancellation Policy Fee per person Cancel up to 120 Days Prior to Program Start Date (applies from date of enroll- -

Full Details (PDF)

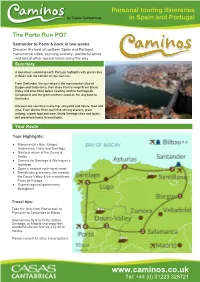

The Porto Run PO7 Santander to Porto & back in two weeks Discover the best of northern Spain and Portugal; monumental cities, stunning scenery, wonderful wines - and lots of other special treats along the way. Summary A round tour combining north Portugal highlights with grand cities in Spain with the comfort of your own car. From Santander, the tour takes in the monumental cities of Burgos and Salamanca, then dives into the magnificent Douro Valley and onto Porto before heading north to Santiago de Compostela and the green northern coast on the way back to Santander. Discover two countries in one trip; vineyards and nature, food and wine. From start to finish you’ll find striking scenery, great walking, superb food and wine, World Heritage cities and lovely, well preserved towns to investigate. Your Route Tour Highlights: • Monumental cities, Burgos, Salamanca, Porto and Santiago • Glorious wines of the Duero & Douro • Camino de Santiago & Wellington’s footsteps • Spain’s verdant north-west coast • Breath-taking scenery, the meseta, the Douro Valley & the magnificent Picos de Europa • Superb regional gastronomy throughout Travel tips: Take the ferry from Portsmouth or Plymouth to Santander or Bilbao. Alternatively fly into Porto, Bilbao, Santiago, or Madrid and enjoy this wonderful circular tour as a fly-drive holiday. Please consult for other travel options www.caminos.co.uk Tel: +44 (0) 01223 328721 Itinerary Overview Stage Itinerary Region Location Hotel, Room * Travel/drive time Arriving Santander or Bilbao 1 Day 1 & 2 Burgos Burgos -

Duero-Douro River Transnational Route Development, Management and Promotion of the Riverside Territory in Spain and Portugal

Duero-Douro River Transnational Route development, management and promotion of the riverside territory in Spain and Portugal Jesús Rivas Iberian Association of Riverside Municipalities of Duero River [email protected] 7 February, 2019 |Cultural Routes Webinar Duero-Douro River Transnational Route Duero-Douro is a transnational route based on the shared identity factors with which the Duero river marks the Spanish and Portuguese regions it passes through: • unique landscapes, • high-quality wine production conditions, • exceptional conditions for the practice of nature tourism and sports, • rich ethnographic (cultural) and natural heritage. 2 Duero-Douro River Transnational Route Source: Urbions’ mountain range (Spain) Mouth: Porto & Vila Nova de Gaia (Portugal) 927km divided in 26 stages (35km average distance) passing through 150 municipalities of Castile and Leon and of the North of Portugal regions Long distance European footpath GR14 3 Duero-Douro River Transnational Route Joining together different stakeholders for the establishment of coherent and common strategies and policies for the Duero river area development Promoting cross-borderWORK cooperation IN between PROGRESS! them (especially between local administrations) and with the support of Interreg A Spain-Portugal. 4 Duero-Douro River Transnational Route 2006 – until today Coordination of the local administrations tourism policies. Valorisation, protection and promotion of the historical and natural cross- border/shared heritage. Development of GPS tracks, for walking -

Análisis Territorial De Castilla Y León Inglés-Español-14-9-17Actualizado

Territorial analysis and identification of Castilla y León 1 This Territorial analysis and identification template is intended to help you to develop your teriitorial analysis. Each section is set up for you to add information that meets your requirements. Table of contents The template comprises five steps in the creation of this analysis: Table of contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 1 Landscape and heritage characterisation ................................................................................. 3 2 Existing knowledge, material and approaches ......................................................................... 10 3 Existing policies on landscape and heritage ............................................................................. 11 4 Ongoing policy development processes .................................................................................. 12 5 looking forward to 2018 Cultural Heritage Year ...................................................................... 13 2 1 Landscape and heritage characterisation Castilla y León, with its 94,147 km2, is an inland region of vast plains bordered by mountains. From east to west crosses the Douro River, whose basin occupies 82% of the territory. The river network dense in mountainous areas, weaker in the central plains, delimits towns and cities and is the lifeblood of the old and new agricultural landscapes, and largely also the landscapes of the industrial era. Rivers, -

'Terroir' the Port Vineyards Are Located in the North East of Portugal in The

Geography and ‘terroir’ The Port vineyards are located in the north east of Portugal in the mountainous upper reaches of the Douro River Valley. This region lies about 130 kilometres inland and is protected from the influence of the Atlantic Ocean by the Marão mountains. The vineyard area is hot and dry in summer and cold in winter, excellent conditions for producing the concentrated and powerful wines needed to make port. The coastal area is humid and temperate, providing the ideal conditions in which to age the wine. The grapes are grown and turned into wine in the vineyards of the Douro Valley. In the spring following the harvest, the wine is brought down to the coast to be aged in the warehouses of the Port houses, known as ‘lodges’. The ‘lodges’ are located in Vila Nova de Gaia, a town located on the south bank of the River Douro facing the old city of Oporto. Until about sixty years ago, the wine was brought down the river from the vineyards to the coast in traditional boats called ‘barcos rabelos’. Most of the vineyards are planted on the steep hillsides of the Douro River valley and those of its tributaries, such as the Corgo, the Távora and the Pinhão. The oldest vineyards are planted on ancient walled terraces, some made over two hundred years ago. These have been classified as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The Douro Valley is considered to be one of the most beautiful and spectacular vineyard areas in the world. The soil of the Douro Valley is very stony and is made up of schist, a kind of volcanic rock. -

Cruise the Douro River August 6Th, 2016- August 15Th, 2016

Cruise the Douro River August 6th, 2016- August 15th, 2016 $2,999 price per person, based on double occupancy, Includes round-trip airfare from Boston to Porto. Visit Lisbon, Sintra, Estoril, Obidos, Fatima and 4 nights cruise in the Douro River. This tour program includes 22 Meals, Fado and Flamenco Show, Wine tasting, all excursions, transfers from airport to hotel and cruise to Porto. 2 Nights at 4 Star Hotel in Lisbon, 4 Night aboard the Spirit of Chartwell and 2 Nights at 4 Star Hotel in Porto. 761 Bedford Street, Fall River, MA 02723 www.sagresvacations.com Ph# 508-679-0053 Indulge your passion for fine dining, culture, and music as you discover the warmth of Portugal and Spain. Experience the “sunny side” of Europe, starting in radiant seaside Lisbon, then follow the Douro River through Portugal and into Spain. Feel the warm sun on your skin as you cruise past terraced hills, quaint villages and acres of ripe vineyards. From taking in a traditional flamenco show to visiting a local café and enjoying authentic Portuguese cuisine and wine tastings, this Sagres Vacations program gives you the very best of the region. August 6th, 2016- Overnight Flight- Board your overnight flight to Lisbon, Portugal. Medieval castles, cobblestone villages, captivating cities and golden-sand beaches, rich in history and natural beauty, experience its charm as the Portuguese welcome you with open arms, and invite you to their “casa”. August 7th, 2016-Lisbon in its glory Enjoy a city tour of Lisbon, Portugal’s rejuvenated capital. Lisbon offers all the delights you’d expect of Portugal’s star attraction, a modern city rooted in century old traditions. -

IRS 2016 Proposal Valladolid, Spain

CANDIDATE TECHNICAL DOSSIER FOR International Radiation Symposium IRS2016 In VALLADOLID (SPAIN), August 2016 Grupo de Optica Atmosférica, GOA-UVA Universidad de Valladolid Castilla y León Spain 1 INDEX I. Introduction…………………………………………………………............. 3 II. Motivation/rationale for holding the IRS in Valladolid………………....….. 3 III. General regional and local interest. Community of Castilla y León…......... 4 IV. The University of Valladolid, UVA. History and Infrastructure………….. 8 V. Conference environment …………………………………………………. 15 VI. Venue description and capacity. Congress Centre Auditorium …….…… 16 VII. Local sites of interest, universities, museums, attractions, parks etc …... 18 VIII. VISA requirements …………………………………………………….. 20 2 IRS’ 2016, Valladolid, Spain I. Introduction We are pleased to propose and host the next IRS at Valladolid, Spain, in August of 2016, to be held at the Valladolid Congress Centre, Avenida de Ramón Pradera, 47009 Valladolid, Spain. A view of the city of Valladolid with the Pisuerga river II. Motivation/rationale for holding the IRS in Valladolid Scientific Interest In the last decades, Spain has experienced a great growth comparatively to other countries in Europe and in the world, not only in the social and political aspects but also in the scientific research. Certainly Spain has a medium position in the world but it potential increases day by day. The research in Atmospheric Sciences has not a long tradition in our country, but precisely, its atmospheric conditions and geographical location makes it one of the best places for atmospheric studies, in topics as radiation, aerosols, etc…. , being a special region in Europe to analyse the impact of climate change. Hosting the IRS’2016 for the first time in Spain would produce an extraordinary benefit for all the Spanish scientific community, and particularly for those groups working in the atmospheric, meteorological and optics research fields. -

Portugal and the Douro River Cruise AIRFARE

Tourcy FREE AIRFARE See back for details 11 DAY RIVER CRUISE HOLIDAY Including two nights in Lisbon, Portugal Portugal and the Douro River Cruise Departure Date: October 13, 2021 Portugal and the Douro River Cruise 11 Days • 22 Meals Spend two nights exploring Lisbon, then set sail through the Portuguese Frontier. Visit Spain’s walled city of Salamanca, and the quaint and historic towns of Portugal along the Douro River. EXCEPTIONAL INCLUSIONS E 22 Meals (9 breakfasts, 5 lunches and 8 dinners) E Airport transfers on tour dates when air is provided by Mayflower Cruises & Tours E Visit two countries E Two-night hotel stay and touring in Lisbon, Portugal before cruising Monument to the Discoveries overlooks the harbor in Lisbon, Portugal E Seven-night cruise on the Emerald Radiance E First-class service by an English-speaking crew E Shore excursions with English-speaking local guides DAY 1 – Depart the USA E All gratuities included Depart the USA on your overnight flight to Lisbon, Portugal. E Personal listening device for onboard excursions E Many meals included onboard with a variety of international DAY 2 – Lisbon, Portugal cuisine Upon arrival, you will be met by a Mayflower Tours representative E Complimentary regional wines, beer and soft drinks and transferred to your hotel. The remainder of the day is at leisure accompany onboard lunches and dinners to explore Lisbon. This evening, join your Mayflower staff and fellow travelers for an included dinner. Meal: D E Onboard Activity Manager will support all EmeraldACTIVE excursions and host daily onboard wellness activities, games, DAY 3 – Discover Lisbon classes and evening entertainment After breakfast, an included tour highlights the famous sites of the E Complimentary bottled water in your stateroom city. -

Application for Geotourism Charter

Application for Geotourism Charter Thank you for the interest in geotourism as a long-term strategy to foster wisely managed tourism and enlightened destination stewardship. National Geographic’s Center for Sustainable Destinations applauds your desire to help protect the world’s distinctive places. The Geotourism Charter is available to any destination that demonstrates a proven track record or credible commitment to pursue development in keeping with the Geotourism Principles (see Appendix I), and defines specific, credible programs to continue destination stewardship and wisely managed tourism. Signing a Geotourism Charter does not require collaboration or partnership with National Geographic Society, unless Society services and recognition are desired. To assist in determining eligibility for a Geotourism Charter, the Center for Sustainable Destinations (CSD) developed this questionnaire. The exercise is useful for any destination seeking to map out an economically beneficial tourism program focused on sustaining and enhancing unique endemic assets. I. Define the geographic boundary of the area represented in this Charter application: The geographic boundary of the Douro Valley Tourism area is defined by the Douro Valley Tourism Plan, which integrates 24 municipalities. The highlights of the many tourist attractions in the region are those classified by UNESCO as World Heritage sites, namely, the “Alto Douro Wine Region” (classified in 2001 by UNESCO as a “living and evolving cultural landscape”), where one of the most significant wines in human history – Port Wine - was born) and “the rock paintings at Foz Côa Valley” (recognized by UNESCO in 1998). In the Douro Valley basin there are also more 2 sites classified as World Heritage by UNESCO: the historical old section of the city of Porto, delineated by the medieval market town (in 1996) and the historical section of Guimarães city. -

March Newsletter 2021

March 2021 CCAASSTTIILLLLAA YY LLEEÓÓNN [inspira] https://www.turismocastillayleon.com/turismocyl/en Río Duero y Puente Románico, Toro, Zamora THE DUERO ROUTE The Duero Route is one of the most important cultural routes in the south of Europe. This route's itinerary splits the region in two and allows tourists to experience the nature, art and gastronomy that the area has to offer. 80% of this route passes through Soria, Burgos, Valladolid, Zamora and Salamanca, 5 of the provinces making up Castilla y León. The river Duero was an important crossroads for the Peninsula in the past. During the time of the Reconquista, it became a border line. This would explain how a large number of its listed buildings, including the castles and monasteries that had been built, determined the future of the surrounding villages. The Duero Route takes tourists to areas of natural beauty that have been formed by the natural course of the river and become important environmental and fauna reserves. The river Duero is also responsible for irrigating the vineyards of southern Europe's most famous grape and wine growing area. It is also the ideal choice for aquatic activities as cruises along the river and water sports in the dams that have been constructed along the river. TOURISM IDEAS IN CASTILLA Y LEÓN CHERRY BLOSSOM BLOOMING IN THE TIÉTAR VALLEY The Tiétar Valley in the south of Ávila is a true paradise protected from the cold by the Sierra de Gredos mountain range. The differences in altitude between the peaks and the bottom of the valley favour the formation of multiple habitats rich in flora and fauna. -

Seasonal and Interannual Variability of the Douro Turbid River Plume, Northwestern Iberian Peninsula

Remote Sensing of Environment 194 (2017) 401–411 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Remote Sensing of Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rse Seasonal and interannual variability of the Douro turbid river plume, northwestern Iberian Peninsula Renato Mendes a,⁎,GonzaloS.Saldíasb,c, Maite deCastro d, Moncho Gómez-Gesteira d, Nuno Vaz a, João Miguel Dias a a CESAM, Departamento de Física, Universidade de Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal b College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA c Centro FONDAP de Investigación en Dinámica de Ecosistemas Marinos de Altas Latitudes (IDEAL), Valdivia, Chile d EPhysLab (Environmental Physics Laboratory), Universidade de Vigo, Facultade de Ciencias, Ourense, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Douro River represents the major freshwater input into the coastal ocean of the northwestern Iberian Pen- Received 17 February 2016 insula. The seasonal and interannual variability of its turbid plume is investigated using ocean color composites Received in revised form 10 March 2017 from MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) sensor aboard the Aqua and Terra satellites Accepted 5 April 2017 (2000–2014) and long-term records of river discharge, wind and precipitation rate. Regional climate indices, Available online xxxx namely the Eastern Atlantic (EA) and North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), were analyzed to identify the influence Keywords: of atmospheric variability on the generation of anomalous turbid river plume patterns. The connection River plumes between the monthly time series of normalized water leaving radiance at 555 nm (nLw(555)) and river discharge MODIS imagery is high (r = 0.81), which indicates a strong link between river outflow and turbidity levels in the river plume. -

A Case Study of Porto and the Northern Region of Portugal

Marketing and Communication of Tourism Organizations on Social Media: A Case Study of Porto and the Northern Region of Portugal by João Neves Introduction The Turismo do Porto e Norte de Portugal (TEM) is the main statist institution dedicated This report is based on a case study12 to the management and promotion of about the impact of social networks on tourism in the Northern region of Portugal; tourism organizations’ marketing and it was created in 2012, resulting from a communication in the Northern region of reform of the tourism sector, which divided Portugal and especially in the city of Porto. continental Portugal into five main tourism The methodology applied in this study was regions. TEM has a tourism promotion based on a selection of relevant entities strategy aimed at seven major segments: (mostly public) that are responsible for the business tourism; city and short breaks; promotion of tourism in Porto and in the gastronomy and wines; nature tourism; Northern Region of Portugal, which have religious tourism; cultural, heritage and a good SEO reputation: they appeared on landscape tourism and well-being and the top positions on the Google search. health tourism. The TEM is present on the The selected entities were Turismo do web through their institutional website3, Porto e Norte de Portugal (a public entity that has content in Portuguese, Spanish of the central administration with a and English, but also on Facebook, Twitter regional focus on the North of Portugal); and YouTube. Visit Porto. (a public web interface of the