Downloaded from Downloaded on 2019-12-02T14:35:12Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viola Lawrence Film Editor

Viola Lawrence film editor This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on 2018-10-22 Finding aid written in English Describing Archives: A Content Standard University Archives and Special Collections Pollak Library South 800 N. State College Blvd. Fullerton, , CA 92831-3599 [email protected] http://www.library.fullerton.edu/services/special-collections.php Viola Lawrence film editor Table Of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents note ........................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical ........................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ........................................................................................................................... 3 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Trophy ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Film Industry Magazines, 1936 - 1971 ...................................................................................................... 4 Viola Lawrence Photographs .................................................................................................................... -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum 4079 Albany Post Road, Hyde Park, NY 12538-1917 www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu 1-800-FDR-VISIT October 14, 2008 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cliff Laube (845) 486-7745 Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library Author Talk and Film: Susan Quinn Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times HYDE PARK, NY -- The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is pleased to announce that Susan Quinn, author of Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times, will speak at the Henry A. Wallace Visitor and Education Center on Sunday, October 26 at 2:00 p.m. Following the talk, Ms. Quinn will be available to sign copies of her book. Furious Improvisation is a vivid portrait of the turbulent 1930s and the Roosevelt Administration as seen through the Federal Theater Project. Under the direction of Hallie Flanagan, formerly of the Vassar Experimental Theatre in Poughkeepsie, New York, the Federal Theater Project was a small but highly visible part of the vast New Deal program known as the Works Projects Administration. The Federal Theater Project provided jobs for thousands of unemployed theater workers, actors, writers, directors and designers nurturing many talents, including Orson Welles, John Houseman, Arthur Miller and Richard Wright. At the same time, it exposed a new audience of hundreds of thousands to live theatre for the first time, and invented a documentary theater form called the Living Newspaper. In 1939, the Federal Theater Project became one of the first targets of the newly-formed House Un-American Activities Committee, whose members used unreliable witnesses to demonstrate that it was infested with Communists. -

A History of Production

A HISTORY OF PRODUCTION 2020-2021 2019-2020 2018-2019 Annie Stripped: Cry It Out, Ohio State The Humans 12 Angry Jurors Murders, The Empty Space Private Lies Avenue Q The Wolves The Good Person of Setzuan john proctor is the villain As It Is in Heaven Sweet Charity A Celebration of Women’s Voices in Musical Theatre 2017-2018 2016-2017 2015-2016 The Cradle Will Rock The Foreigner Reefer Madness Sense and Sensibility Upton Abbey Tartuffe The Women of Lockerbie A Piece of my Heart Expecting Isabel 9 to 5 Urinetown Hello, Dolly! 2014-2015 2013-2014 2012-2013 Working The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later The Miss Firecracker Contest Our Town The 25th Annual Putnam County The Drowsy Chaperone Machinal Spelling Bee Anna in the Tropics Guys and Dolls The Clean House She Stoops to Conquer The Lost Comedies of William Shakespeare 2011-2012 2010-2011 2009-2010 The Sweetest Swing in Baseball Biloxi Blues Antigone Little Shop of Horrors Grease Cabaret Picasso at the Lapin Agile Letters to Sala How I Learned to Drive Love’s Labour’s Lost It’s All Greek to Me Playhouse Creatures 2008-2009 2007-2008 2006-2007 Doubt Equus The Mousetrap They’re Playing Our Song Gypsy Annie Get Your Gun A Midsummer Night’s Dream The Importance of Being Earnest Rumors I Hate Hamlet Murder We Wrote Henry V 2005-2006 2004-2005 2003-2004 Starting Here, Starting Now Oscar and Felix Noises Off Pack of Lies Extremities 2 X Albee: “The Sandbox” and “The Zoo All My Sons Twelfth Night Story” Lend Me a Tenor A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the The Triumph of Love Ukraine Babes in Arms -

Gloria Swanson

Gloria Swanson: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Title: Gloria Swanson Papers [18--]-1988 (bulk 1920-1983) Dates: [18--]-1988 Extent: 620 boxes, artwork, audio discs, bound volumes, film, galleys, microfilm, posters, and realia (292.5 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this well-known American actress encompass her long film and theater career, her extensive business interests, and her interest in health and nutrition, as well as personal and family matters. Call Number: Film Collection FI-041 Language English. Access Open for research. Please note that an appointment is required to view items in Series VII. Formats, Subseries I. Realia. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase (1982) and gift (1983-1988) Processed by Joan Sibley, with assistance from Kerry Bohannon, David Sparks, Steve Mielke, Jimmy Rittenberry, Eve Grauer, 1990-1993 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Film Collection FI-041 Biographical Sketch Actress Gloria Swanson was born Gloria May Josephine Swanson on March 27, 1899, in Chicago, the only child of Joseph Theodore and Adelaide Klanowsky Swanson. Her father's position as a civilian supply officer with the army took the family to Key West, FL and San Juan, Puerto Rico, but the majority of Swanson's childhood was spent in Chicago. It was in Chicago at Essanay Studios in 1914 that she began her lifelong association with the motion picture industry. She moved to California where she worked for Sennett/Keystone Studios before rising to stardom at Paramount in such Cecil B. -

An Educational Guide Filled with Youthful Bravado, Welles Is a Genius Who Is in Love with and Welles Began His Short-Lived Reign Over the World of Film

Welcome to StageDirect Continued from cover Woollcott and Thornton Wilder. He later became associated with StageDirect is dedicated to capturing top-quality live performance It’s now 1942 and the 27 year old Orson Welles is in Rio de Janeiro John Houseman, and together, they took New York theater by (primarily contemporary theater) on digital video. We know that there is on behalf of the State Department, making a goodwill film for the storm with their work for the Federal Theatre Project. In 1937 their tremendous work going on every day in small theaters all over the world. war effort. Still struggling to satisfy RKO with a final edit, Welles is production of The Cradle Will Rock led to controversy and they were This is entertainment that challenges, provokes, takes risks, explodes forced to entrust Ambersons to his editor, Robert Wise, and oversee fired. Soon after Houseman and Welles founded the Mercury Theater. conventions - because the actors, writers, and stage companies are not its completion from afar. The company soon made the leap from stage to radio. slaves to the Hollywood/Broadway formula machine. These productions It’s a hot, loud night in Rio as Orson Welles (actor: Marcus In 1938, the Mercury Theater’s War of the Worlds made appear for a few weeks, usually with little marketing, then they disappear. Wolland) settles in to relate to us his ‘memoir,’ summarizing the broadcast history when thousands of listeners mistakenly believed Unless you’re a real fanatic, you’ll miss even the top performances in your early years of his career in theater and radio. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume8,Number 1 Spring1990 Kurt Weill IN THIS ISSUE 1990 KURT W EILL FESTIVAL IN NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 7 (Re-) Unification? by Christopher Hailey 9 Der Kuhhandel by Michael Morley 11 Niederrheinische Chorgemeinschaft review by Jurgen Thym 12 KURT-WED.,L-FESTIVAL Robert-Schumann-Hochschule concert review by Gunther Diehl 13 Teacher Workshops in Heek 13 Exhibitions 14 Press Clippings 15 COLUMNS News in Brief 2 Letters to the Editor 5 New Publications 16 Selected Performances 27 BooKs Studien zur Berliner Musikgeschichte edited by Traude Ebert-Obermeier 18 PERFORMANCES Street Scene at the English National Opera 20 Sinfonia San Francisco 21 Lady in the Dark at Light Opera Works 22 \-.il!N'! ~pt.-a.hl~ll~ail Seven Deadly Sins atTheJuilliard School 23 l,,lllll•~-'ll~,l......,._1,_.. ,,.,,..._,'ftt~nt '\1l~.11,....,..'(11tt lt11.-.....t.., 3-ld•llrilrll ..-•1fw......... Ji,d~(ontllldilt , l""NNW"a.....iK,..1 11.-fw-,.,,,...,t ~,\ Downtown Chamber and Opera Players 24 RECORDINGS Die Dreigroschenoper on Decca/London 25 7 North Rhine Westphalia Christopher Hailey analyzes th e significance of the festival and symposium, Mich ael Morley critiques Der Kuhha ndel, J u rgen Thym an d Gunt h er Diehl report on concerts. Also news articles, p hotos, and p ress clippings. 2 The American Musical Theater Festival opens the first professional revival of Love Life on 10 June at the Walnut Theatre in Philadelphia. The show runs through 24 June, with Almeida Festival in London performances at 8:00 PM Tuesday-Saturday and matinees on 13, 16, 20, and 24 June at 2:00 PM. -

Gloria Swanson

Gloria Swanson: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Title: Gloria Swanson Papers Dates: [18--]-1988 Extent: 620 boxes, artwork, audio discs, bound volumes, film, galleys, microfilm, posters, and realia (292.5 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this well-known American actress encompass her long film and theater career, her extensive business interests, and her interest in health and nutrition, as well as personal and family matters. Call Number: Film Collection FI-041 Language English. Access Open for research. Please note that an appointment is required to view items in Series VII. Formats, Subseries I. Realia. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase (1982) and gift (1983-1988) Processed by Joan Sibley, with assistance from Kerry Bohannon, David Sparks, Steve Mielke, Jimmy Rittenberry, Eve Grauer, 1990-1993 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Film Collection FI-041 Biographical Sketch Actress Gloria Swanson was born Gloria May Josephine Swanson on March 27, 1899, in Chicago, the only child of Joseph Theodore and Adelaide Klanowsky Swanson. Her father's position as a civilian supply officer with the army took the family to Key West, FL and San Juan, Puerto Rico, but the majority of Swanson's childhood was spent in Chicago. It was in Chicago at Essanay Studios in 1914 that she began her lifelong association with the motion picture industry. She moved to California where she worked for Sennett/Keystone Studios before rising to stardom at Paramount in such Cecil B. DeMille features as Male and Female (1919) and The Affairs of Anatol (1921). -

THE OTHER SIDE of the WIND; a LOST MOTHER, a MAVERICK, ROUGH MAGIC and a MIRROR: a PSYCHOANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE on the CINEMA of ORSON WELLES by Jack Schwartz

Schwartz, J. (2019). The Other Side of the Wind…A psychoanalytic perspective on the cinema of Orson Welles. MindConsiliums, 19(8), 1-25. THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND; A LOST MOTHER, A MAVERICK, ROUGH MAGIC AND A MIRROR: A PSYCHOANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE ON THE CINEMA OF ORSON WELLES By Jack Schwartz ABSTRACT Arguably, Orson Welles is considered America’s most artistic and influential filmmaker from the golden era of American movies, even though most people are only familiar with his first feature, Citizen Kane (1941). Any film buff can easily recognize his signature camera work, his use of lighting and overlapping dialogue, along with so many cinematic nuisances that define his artistry. Despite being on the “pantheon” (Sarris, 1969) of American directors, he never established any real sustaining commercial success. Even though he leaves behind many pieces of a giant beautiful cinematic puzzle, Welles will always be considered one of the greats. Prompted by Welles’ posthumously restored last feature The Other Side of the Wind (2018), the time is ripe for a psychoanalytic re-evaluation of Welles’ cinematic oeuvre, linking the artist’s often tumultuous creative journey to the dynamic structure of Welles’ early and later childhood experiences through the frame of his final film. INTRODUCTION From early in its invention, movies have offered the gift of escaping the grind of daily life, even when movies are sometimes about the grind of daily life. Movies move us, confront us, entertain us, break our hearts, help mend our broken hearts, teach us things, give us a place to practice empathy or express anger and point to injustice. -

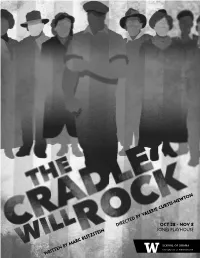

The Cradle Will Rock Program

THE CRADLE WILL ROCK written by Marc blitzstein directed by valerie curtis-newton^° Scenic Design Lighting Design Musical Directors Technical Director Stage Manager Jennifer Zeyl^ Kyle Soble* Scott Hafso^° Alex Danilchik^ Robin Obourn José Gonzales Costume Design Sound Design Fawn Bartlett* Jacob Israel * Member of the Master of Fine Arts Program in Design ^Alumnus/Alumna of UW Drama °Faculty of UW Drama Prop Master Asst. Costume Designer Costume Crew Jake Lemberg Andrea Bush^ Monica Gonzalez Lindsey Crocker Becky Su Emma Halliday Lingjiao Wang Assistant Stage Managers Asst. Lighting Designer Hannah Knapp-Jenkins Megan Bernovich Amber Parker* Caitlin Manske Photographer Aaron Jin Lina Phan Mike Hipple Model Builder House Manager Montana Tippett Laundry Tickets Monica Gonzalez ArtsUW Ticket Office Light Board Operator Samantha de Jong Asst. Scenic Designer Jacqueline Wagner Running Crew Julia Welch^ Gabi Boettner Ross Jackson Yuchen Jin Mercedes Larkin Special Thanks: 5th Avenue Theatre, ACT Theatre, Jerry Chambers, Seattle Children's Theatre, Seattle Opera, Seattle Repertory Theatre, Theatre Puget Sound, UW Student Technology Fee, Village Theatre *member of the Professional Actor Training Program (PATP) CAST ^Alumnus/Alumna of UW Drama °Faculty of UW Drama John Houseman....................................... Andrew McMasters^ Editor Daily.............................................. AJ Friday* Orson Welles............................................ Andrew Russell Yasha........................................................ Hazel Lozano* -

O PODER VAI DANÇAR (Cradle Will Rock) EUA, 1999

O PODER VAI DANÇAR (Cradle Will Rock) EUA, 1999. Cor, 35mm, 133 min. Oficina Cine-Escola e Filmes do Estação apresentam Ficha Técnica direção TIM ROBBINS roteiro TIM ROBBINS produção LYDIA DEAN PILCHER, JON KILIK e TIM ROBBINS fotografia JEAN-YVES ESCOFFIER direção de arte CHRISTA MUNRO edição GÉRALDINE PERONIA elenco JOHN TURTURRO, EMILY WATSON, JOHN CUSACK, JOAN CUSACK, VANESSA REDGRAVE, SUSAN SARANDON, ANGUS MACFADYEN E BILL MURRAY. O PODER VAI DANÇAR Sinopse Nos anos de 1930, Nova York vive um período de ebulição política e cultural. Sindicatos de trabalhadores lutam por melhores salários. Grandes industriais se aproximam do Fascismo Europeu. As políticas públicas são acusadas de promover o comunismo. Um então desconhecido diretor de teatro, Orson Welles, e sua equipe de atores preparam um musical sobre a opressão em uma pequena cidade e a luta de seus cidadãos para derrubar os corruptos do poder. Gênero: drama / histórico Classificação etária: 16 anos Tim Robbins nasceu na Califórnia, mas foi criado em Nova York. Iniciou sua carreira atuando na televisão e no teatro. Participava de uma trupe teatral chamada The Actors Gang, através da qual entrou em contato com o cinema. Ficou conhecido como ator de cinema a partir de O Jogador (1992), de Robert Altman. No mesmo ano, estreou atrás das câmaras, dirigindo e escrevendo o roteiro de Bob Roberts. Também assina a direção de Os Últimos Passos de um Homem (1995). Debate após a sessão com Rubim Aquino, professor e historiador. de Tim Robbins Grupo Estação: 20 anos projetando a diferença. Oficina Cine-Escola é um programa permanente de formação de público, Informações: que desde 1985 desenvolve ações que exploram o cinema como instrumento educativo. -

JO: . . . You Got on the Federal Theatre, How You Became Involved in It, and Why out in Roslyn

JO: . you got on the Federal Theatre, how you became involved in it, and why out in Roslyn. BE: Oh, well, I was--I had come from Alabama and gone to a dramatic school here in New York which no longer exists, called the Feagin School of Dramatic Arts. And on the faculty there were several people in the theatre. The person who taught stage design was a man named Dr. Milton Smith, who was the head of drama at Columbia University, and he taught there. Also a man who taught and directed was a man named Charles Hopkins, who I got to know at that time. And it was Charles Hopkins who had been--I don't know exactly what his title was. I think he was certainly, not New York City, but I think this area of New York State, head of the New York State Federal Theatre. I think they had been up in White Plains or some place before. But Hoppie, years before, had had a theatre in Roslyn which was called the Theatre of the Four Seasons, and he was very fond of that theatre. So he somehow moved the whole setup back to Roslyn, which was a charming little theatre, which is now the Public Library of Roslyn, I believe, that they took out the stage. And next to it was a beautiful 18th century farmhouse tithe middle of a park with a lake. He liked that and so that sort of became his seat at the time. And so he asked me to come out and design scenery there. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room.