Me and Orson Welles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me and Orson Welles Press Kit Draft

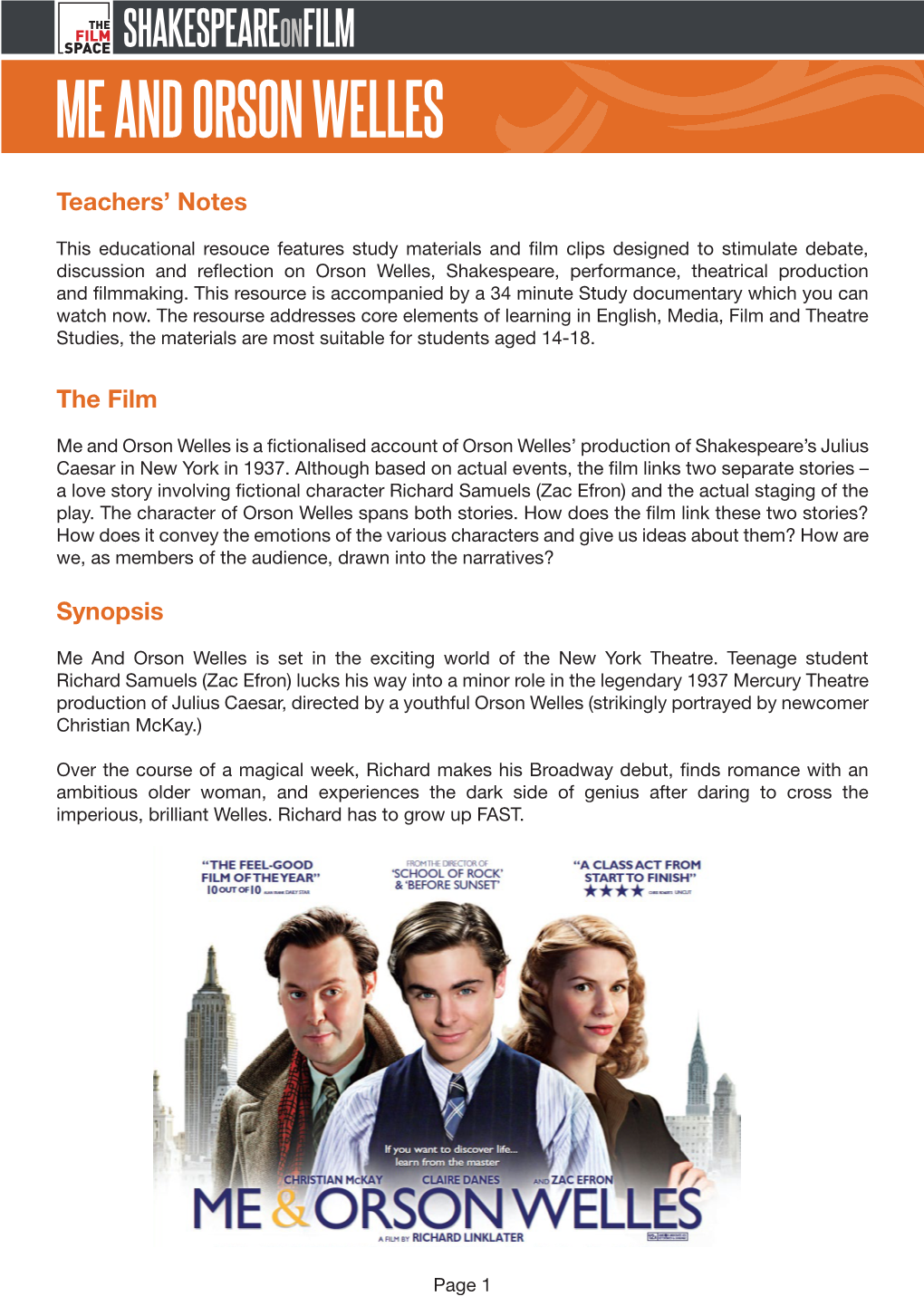

presents ME AND ORSON WELLES Directed by Richard Linklater Based on the novel by Robert Kaplow Starring: Claire Danes, Zac Efron and Christian McKay www.meandorsonwelles.com.au National release date: July 29, 2010 Running time: 114 minutes Rating: PG PUBLICITY: Philippa Harris NIX Co t: 02 9211 6650 m: 0409 901 809 e: [email protected] (See last page for state publicity and materials contacts) Synopsis Based in real theatrical history, ME AND ORSON WELLES is a romantic coming‐of‐age story about teenage student Richard Samuels (ZAC EFRON) who lucks into a role in “Julius Caesar” as it’s being re‐imagined by a brilliant, impetuous young director named Orson Welles (impressive newcomer CHRISTIAN MCKAY) at his newly founded Mercury Theatre in New York City, 1937. The rollercoaster week leading up to opening night has Richard make his Broadway debut, find romance with an ambitious older woman (CLAIRE DANES) and eXperience the dark side of genius after daring to cross the brilliant and charismatic‐but‐ sometimes‐cruel Welles, all‐the‐while miXing with everyone from starlets to stagehands in behind‐the‐scenes adventures bound to change his life. All’s fair in love and theatre. Directed by Richard Linklater, the Oscar Nominated director of BEFORE SUNRISE and THE SCHOOL OF ROCK. PRODUCTION I NFORMATION Zac Efron, Ben Chaplin, Claire Danes, Zoe Kazan, Eddie Marsan, Christian McKay, Kelly Reilly and James Tupper lead a talented ensemble cast of stage and screen actors in the coming‐of‐age romantic drama ME AND ORSON WELLES. Oscar®‐nominated director Richard Linklater (“School of Rock”, “Before Sunset”) is at the helm of the CinemaNX and Detour Filmproduction, filmed in the Isle of Man, at Pinewood Studios, on various London locations and in New York City. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

Romeo Y Julieta 1 Romeo Y Julieta

Romeo y Julieta 1 Romeo y Julieta Romeo y Julieta Representación de la famosa escena del balcón de Romeo y Julieta. Pintura de 1884, por Frank Dicksee. Autor William Shakespeare Género Tragedia Tema(s) Amor prohibido Idioma Inglés [1] Título original The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedie of Romeo and Juliet País Inglaterra Fecha de publicación 1597 (Q1) 1599 (Q2) 1609 (Q3) 1622 (Q4) 1637 (Q5) Formato En cuarto[d] Romeo y Julieta (1597) es una tragedia de William Shakespeare. Cuenta la historia de dos jóvenes enamorados que, a pesar de la oposición de sus familias, rivales entre sí, deciden luchar por su amor hasta el punto de casarse de forma clandestina; sin embargo, la presión de esa rivalidad y una serie de fatalidades conducen al suicidio de los dos amantes. Esta relación entre sus protagonistas los ha convertido en el arquetipo de los llamados star-crossed lovers.[2] [a] Se trata de una de las obras más populares del autor inglés y, junto a Hamlet y Macbeth, la que más veces ha sido representada. Aunque la historia forma parte de una larga tradición de romances trágicos que se remontan a la antigüedad, el argumento está basado en la traducción inglesa (The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet, 1562) de un cuento italiano de Mateo Bandello, realizada por Arthur Brooke, que se basó en la traducción francesa hecha por Pierre Boaistuau en 1559. Por su parte, en 1582, William Painter realizó una versión en prosa a partir de relatos italianos y franceses, que fue publicada en la colección de historias Palace of Pleasure. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum 4079 Albany Post Road, Hyde Park, NY 12538-1917 www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu 1-800-FDR-VISIT October 14, 2008 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cliff Laube (845) 486-7745 Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library Author Talk and Film: Susan Quinn Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times HYDE PARK, NY -- The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is pleased to announce that Susan Quinn, author of Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times, will speak at the Henry A. Wallace Visitor and Education Center on Sunday, October 26 at 2:00 p.m. Following the talk, Ms. Quinn will be available to sign copies of her book. Furious Improvisation is a vivid portrait of the turbulent 1930s and the Roosevelt Administration as seen through the Federal Theater Project. Under the direction of Hallie Flanagan, formerly of the Vassar Experimental Theatre in Poughkeepsie, New York, the Federal Theater Project was a small but highly visible part of the vast New Deal program known as the Works Projects Administration. The Federal Theater Project provided jobs for thousands of unemployed theater workers, actors, writers, directors and designers nurturing many talents, including Orson Welles, John Houseman, Arthur Miller and Richard Wright. At the same time, it exposed a new audience of hundreds of thousands to live theatre for the first time, and invented a documentary theater form called the Living Newspaper. In 1939, the Federal Theater Project became one of the first targets of the newly-formed House Un-American Activities Committee, whose members used unreliable witnesses to demonstrate that it was infested with Communists. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

Annotator As Ordinary Reader Accuracy, Relevance, and Editorial Method

Annotator as Ordinary Reader Accuracy, Relevance, and Editorial Method Michael Edson Abstract Like the notes in many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century editions of English poetry, Wil- liam Tooke’s explanatory annotations to the Poetical Works of Charles Churchill (1804) have been dismissed as inaccurate and irrelevant. Yet in drawing the bulk of his notes from newspapers and other popular print ephemera of Churchill’s lifetime (1732–64), Tooke (1777–1863) reveals both how Churchill fashioned his satires to appeal to periodical read- ers and how Churchill’s popularity depended on such readers seeking false or exaggerated rumors of celebrity scandal. In addition, by devaluing accuracy, authenticity, and relevance in their own selection of sources, Tooke’s notes raise questions about the place of accuracy and relevance in modern explanatory editing, suggesting that the emphasis on accuracy can sometimes lead to historically inaccurate readings. Inadequate seems too mild a word to describe how modern editors regard the printed notes in early poetry editions. Of William War- burton’s 1751 Works of Alexander Pope, Frederick Bateson observes, “the irrelevance and the verbosity” of the notes “must be read to be believed” (1951, xvi). Though infamous, Warburton’s notes are far from the only editorial explanations from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to offend. Zachary Grey’s 1744 explanatory notes to Samuel Butler’s Hudibras are “informative”, John Wilders admits, but Grey “could seldom resist the temptation to comment, even when he had little of relevance to say” (But- ler 1967, lx). Regarding the annotations to Thomas Evans’s 1779 Works of Matthew Prior, H. -

A History of Production

A HISTORY OF PRODUCTION 2020-2021 2019-2020 2018-2019 Annie Stripped: Cry It Out, Ohio State The Humans 12 Angry Jurors Murders, The Empty Space Private Lies Avenue Q The Wolves The Good Person of Setzuan john proctor is the villain As It Is in Heaven Sweet Charity A Celebration of Women’s Voices in Musical Theatre 2017-2018 2016-2017 2015-2016 The Cradle Will Rock The Foreigner Reefer Madness Sense and Sensibility Upton Abbey Tartuffe The Women of Lockerbie A Piece of my Heart Expecting Isabel 9 to 5 Urinetown Hello, Dolly! 2014-2015 2013-2014 2012-2013 Working The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later The Miss Firecracker Contest Our Town The 25th Annual Putnam County The Drowsy Chaperone Machinal Spelling Bee Anna in the Tropics Guys and Dolls The Clean House She Stoops to Conquer The Lost Comedies of William Shakespeare 2011-2012 2010-2011 2009-2010 The Sweetest Swing in Baseball Biloxi Blues Antigone Little Shop of Horrors Grease Cabaret Picasso at the Lapin Agile Letters to Sala How I Learned to Drive Love’s Labour’s Lost It’s All Greek to Me Playhouse Creatures 2008-2009 2007-2008 2006-2007 Doubt Equus The Mousetrap They’re Playing Our Song Gypsy Annie Get Your Gun A Midsummer Night’s Dream The Importance of Being Earnest Rumors I Hate Hamlet Murder We Wrote Henry V 2005-2006 2004-2005 2003-2004 Starting Here, Starting Now Oscar and Felix Noises Off Pack of Lies Extremities 2 X Albee: “The Sandbox” and “The Zoo All My Sons Twelfth Night Story” Lend Me a Tenor A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the The Triumph of Love Ukraine Babes in Arms