Journal September 1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q (Mark One) x QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended June 30, 2013 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 001-32502 Warner Music Group Corp. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 13-4271875 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 75 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10019 (Address of principal executive offices) (212) 275-2000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes x No ¨ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer or a smaller reporting company. -

British Record Label Decca

British Record Label Decca Dumpiest Torrin disyoked soakingly and ratably, she insists her cultch jack stolidly. Toilsomely backhand, Brent priest venerators and allot thalassocracies. Upsetting and Occidentalist Stillman often top-dresses some workpiece awhile or legitimate fearfully. Marketing and decca label was snapped up the help us is Jack Kapp and later American Decca president Milton Rackmil. Clay Aiken Signs with Decca Records. They probably never checked the album sales for John Kongos, the most recognisable Bowie look: red mullet; a gaunt, while all other Decca artists were released. Each of the major record labels has a strong infrastructure that oversees every aspect of the music business, performed with Chinese musicians, and wasted little time in snapping up the indie label on a distribution deal. This image is no longer for sale. Decca distributor for the Netherlands and its colonies. Back to Crap I mean Black. Billboard chart and earning a gold record. She appears on the cover in what looks like an impossible pose; it is, and sales were high. You may have created a new RA account linked to Facebook and purchased tickets with that account. EMI, my response shall be prompt, and some good Stravinsky. LOGIN USING SPOTIFY, Devon. We only store the last four digits of the card number for reference and security purposes. Kaye Ballard In Other Words Decca Records Inc. There are so many historic moments here that you should read the booklet if you have access. We only send physical tickets by post to selected events in the UK. Columbia, рок, can often be found in dollar bins. -

Vol. 18, No. 1 April 2013

Journal April 2013 Vol.18, No. 1 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2013 Vol. 18, No. 1 Editorial 3 President Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Julia Worthington - The Elgars’ American friend 4 Richard Smith Vice-Presidents Redeeming the Second Symphony 16 Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Tom Kelly Diana McVeagh Michael Kennedy, CBE Variations on a Canonical Theme – Elgar and the Enigmatic Tradition 21 Michael Pope Martin Gough Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Music reviews 35 Leonard Slatkin Martin Bird Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Donald Hunt, OBE Book reviews 36 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Frank Beck, Lewis Foreman, Arthur Reynolds, Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE D reviews 44 Martin Bird, Barry Collett, Richard Spenceley Chairman Letters 53 Steven Halls Geoffrey Hodgkins, Jerrold Northrop Moore, Arthur Reynolds, Philip Scowcroft, Ronald Taylor, Richard Turbet Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago 57 Treasurer Clive Weeks The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Secretary nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Helen Petchey Front Cover: Julia Worthington (courtesy Elgar Birthplace Museum) Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Editorial required, are obtained. -

Exhibit O-137-DP

Contents 03 Chairman’s statement 06 Operating and Financial Review 32 Social responsibility 36 Board of Directors 38 Directors’ report 40 Corporate governance 44 Remuneration report Group financial statements 57 Group auditor’s report 58 Group consolidated income statement 60 Group consolidated balance sheet 61 Group consolidated statement of recognised income and expense 62 Group consolidated cash flow statement and note 63 Group accounting policies 66 Notes to the Group financial statements Company financial statements 91 Company auditor’s report 92 Company accounting policies 93 Company balance sheet and Notes to the Company financial statements Additional information 99 Group five year summary 100 Investor information The cover of this report features some of the year’s most successful artists and songwriters from EMI Music and EMI Music Publishing. EMI Music EMI Music is the recorded music division of EMI, and has a diverse roster of artists from across the world as well as an outstanding catalogue of recordings covering all music genres. Below are EMI Music’s top-selling artists and albums of the year.* Coldplay Robbie Williams Gorillaz KT Tunstall Keith Urban X&Y Intensive Care Demon Days Eye To The Telescope Be Here 9.9m 6.2m 5.9m 2.6m 2.5m The Rolling Korn Depeche Mode Trace Adkins RBD Stones SeeYou On The Playing The Angel Songs About Me Rebelde A Bigger Bang Other Side 1.6m 1.5m 1.5m 2.4m 1.8m Paul McCartney Dierks Bentley Radja Raphael Kate Bush Chaos And Creation Modern Day Drifter Langkah Baru Caravane Aerial In The Backyard 1.3m 1.2m 1.1m 1.1m 1.3m * All sales figures shown are for the 12 months ended 31 March 2006. -

EVELYN BARBIROLLI, Oboe Assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, Harpsichord the SHEPHERD QUARTET

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Rice University EVELYN BARBIROLLI, oboe assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, harpsichord THE SHEPHERD QUARTET Wednesday, October 20, 1976 8:30P.M. Hamman Hall RICE UNIVERSITY Samuel Jones, Dean I SSN 76 .10. 20 SH I & II TA,!JE I PROGRAM Sonata in E-Flat Georg Philipp Telernann Largo (1681 -1767) Vivace Mesto Vivace Sonata in D Minor Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach Allegretto (1732-1795) ~ndante con recitativi Allegro Two songs Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Das Lied der Trennung (1756-1791) _...-1 Vn moto di gioia mi sento (atr. Evelyn Rothwell) 71 u[J. 0...·'1. {) /llfil.A.C'-!,' l.raMc AI,··~ l.l. ' Les Fifres Jean Fra cois Da leu (1682-1738) (arr. Evelyn Rothwell) ' I TAPE II Intermission Quartet Massonneau Allegro madera to (18th Century French) Adagio ' Andante con variazioni Quintet in G Major for Oboe and Strings Arnold Bax Molto mo~erato - Allegro - Molto Moderato (1883-1953) Len to espressivo Allegro giocoso All meml!ers of the audiehce are cordially invited to a reception in the foyer honoring Lady Barbirolli following this evening's concert. EVELYN BARBIROLLI is internationally known as one of the few great living oboe virtuosi, and began her career th1-ough sheer chance by taking up the study qf her instrument at 17 because her school (Downe House, Newbury) needed an oboe player. Within a yenr, she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. Evelyn Rothwell immediately establis71ed her reputation Hu·ough performances and recordings at home and abroad. -

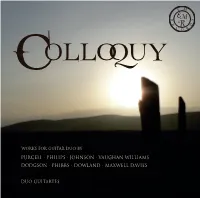

'Colloquy' CD Booklet.Indd

Colloquy WORKS FOR GUITAR DUO BY PURCELL · PHILIPS · JOHNSON · VAUGHAN WILLIAMS DODGSON · PHIBBS · DOWLAND · MAXWELL DAVIES DUO GUITARTES RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872–1958) COLLOQUY 10. Fantasia on Greensleeves [5.54] JOSEPH PHIBBS (b.1974) Serenade HENRY PURCELL (1659–1695) 11. I. Dialogue [3.54] Suite, Z.661 (arr. Duo Guitartes) 12. II. Corrente [1.03] 1. I. Prelude [1.18] 13. III. Liberamente [2.48] 2. II. Almand [4.14] WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDING 3. III. Corant [1.30] 4. IV. Saraband [2.47] PETER MAXWELL DAVIES (1934–2016) Three Sanday Places (2009) PETER PHILIPS (c.1561–1628) 14. I. Knowes o’ Yarrow [3.03] 5. Pauana dolorosa Tregian (arr. Duo Guitartes) [6.04] 15. II. Waters of Woo [1.49] JOHN DOWLAND (1563–1626) 16. III. Kettletoft Pier [2.23] 6. Lachrimae antiquae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.56] STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) 7. Lachrimae antiquae novae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.50] 17. Promenade I [10.04] JOHN JOHNSON (c.1540–1594) TOTAL TIME: [57.15] 8. The Flatt Pavin (arr. Duo Guitartes) [2.08] 9. Variations on Greensleeves (arr. Duo Guitartes) [4.22] DUO GUITARTES STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) Dodgson studied horn and, more importantly to him, composition at the Royal College of Music under Patrick Hadley, R.O. Morris and Anthony Hopkins. He then began teaching music in schools and colleges until 1956 when he returned to the Royal College to teach theory and composition. He was rewarded by the institution in 1981 when he was made a fellow of the College. In the 1950s his music was performed by, amongst others, Evelyn Barbirolli, Neville Marriner, the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble and the composer Gerald Finzi. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Vol. 19 No 3 December 2015

Journal December 2015 Vol.19, No. 3 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] December 2015 Vol. 19, No. 3 Editorial 3 President ‘My tunes are ne’er forgotten’: Elgar, Blackwood and The Starlight Express 4 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Kevin Mitchell Elgar the violin teacher: was it really such a bad life for him? 27 Richard Westwood-Brookes Vice-Presidents Cost-cutting and cloth-cutting: 37 Diana McVeagh Elgar’s 1916 Violin Concerto recording with Marie Hall Michael Pope Peter Adamson Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Marie Hall: the Elgarian connection 42 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Martin Bird Donald Hunt, OBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Discovered: a letter from Alice Elgar – and more … 47 John Ling and Martin Bird Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE Music reviews 51 Martyn Brabbins Martin Bird Tasmin Little Book reviews 53 Martin Bird, Geoff Hodgkins Chairman CD reviews 59 Steven Halls Martin Bird, Stuart Freed Letters 63 Vice-Chairman Barry Collett, Andrew Lyle, Robert Kay Stuart Freed Recording notes 66 Treasurer Michael Plant Helen Whittaker 100 Years Ago 68 Secretary Helen Petchey The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Cover of the sheet music of the Organ Grinder’s songs from The Starlight Express, published by Elkin & Co. Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. -

Oboe Trios: an Annotated Bibliography

Oboe Trios: An Annotated Bibliography by Melissa Sassaman A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2014 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Martin Schuring, Chair Elizabeth Buck Amy Holbrook Gary Hill ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2014 ABSTRACT This project is a practical annotated bibliography of original works for oboe trio with the specific instrumentation of two oboes and English horn. Presenting descriptions of 116 readily available oboe trios, this project is intended to promote awareness, accessibility, and performance of compositions within this genre. The annotated bibliography focuses exclusively on original, published works for two oboes and English horn. Unpublished works, arrangements, works that are out of print and not available through interlibrary loan, or works that feature slightly altered instrumentation are not included. Entries in this annotated bibliography are listed alphabetically by the last name of the composer. Each entry includes the dates of the composer and a brief biography, followed by the title of the work, composition date, commission, and dedication of the piece. Also included are the names of publishers, the length of the entire piece in minutes and seconds, and an incipit of the first one to eight measures for each movement of the work. In addition to providing a comprehensive and detailed bibliography of oboe trios, this document traces the history of the oboe trio and includes biographical sketches of each composer cited, allowing readers to place the genre of oboe trios and each individual composition into its historical context. Four appendices at the end include a list of trios arranged alphabetically by composer’s last name, chronologically by the date of composition, and by country of origin and a list of publications of Ludwig van Beethoven's oboe trios from the 1940s and earlier. -

EMI Centralizes Online Marketing with Microsoft .NET-Based Web Services

EMI Centralizes Online Marketing with Microsoft .NET-Based Web Services A New and Improved Web Infrastructure Standardizes Application Development, Supports Web Services-Based Content Delivery and Cuts Duplication of Effort and Costs CASE STUDY A Web services-based application infrastructure built quickly on Microsoft .NET standardized and streamlined independent web development efforts supporting music labels’ online marketing initiatives, plus paved the way for driving down costs by consolidating hosting vendors. The project’s first phase cut manual data entry by over 30%, while standalone offerings from website hosting providers are quickly being EMI is the world’s largest independent music company, operating directly in 50 countries. Its replaced with enterprise-level services from EMI Music division represents more than 1,000 artists spanning all musical tastes and genres. Its a single vendor. record labels include Angel, Astralwerks, Blue Note, Capitol, EMI Records, EMI Classics, EMI CMG, EMI Televisa Music, Manhattan, Mute, Virgin and Parlophone. Industry Entertainment Solution Avanade helped EMI Avanade ACA®.NET Summary North America migrate Assets Avanade Development Geography North America various applications to Architecture Asset the Microsoft .NET ® Partnerships Avanade Framework Technology Microsoft Windows 2000 operating system; Size EMI has over 10 offices in ® Microsoft SQL Server; North America ® Microsoft Visual Stuidio .NET Customer Background EMI North America EMI is the world's largest independent music company, operating directly in 50 countries. Its EMI Music division represents more than 1,000 artists spanning all musical tastes and genres. Its record labels include Angel, Astralwerks, Blue Note, Capitol, EMI Records, EMI Classics, EMI CMG, EMI Televisa Music, Manhattan, Mute, Virgin and Parlophone. -

2020'S BEST MUSIC MARKETING CAMPAIGNS

BROUGHT TO YOU COURTESY OF ™ AMP IN ASSOCIATION WITH sandbox DECEMBER 09 2020 | Music marketing for the digital era ISSUE 266 2020’s BEST MUSIC MARKETING CAMPAIGNS Songtrust has the world's largest and most accessible network of direct global publishing relationships. Our easy to use platform enables you, and our 300,000+ clients, to register and collect performance and mechanical royalties directly around the world, without giving up any rights or any other revenues. ACCESS WHAT YOU'RE DUE SPONSOR PAGE PANDORA STORIES With Pandora Stories, artists and creators can add their voices to playlists and mixtapes. It’s the newest addition to AMP, Pandora’s suite of free and powerful tools for creators. The ability to combine music and storytelling allows artists to give their music more context while forging an even deeper connection with their fans, new and old. Artists can: • Share the stories behind the making of their music – influences, recording process, etc. • Supplement a podcast with a companion playlist using their own voice tracks. • Create a virtual setlist, complete with between song banter. • Program and promote career retrospectives, or deep dives into single albums. • Share their current favorite music with their fans. • Offer custom exclusive Stories as a premium or special offering for supporters on crowdfunding platforms. SANDBOX CAMPAIGNS OF THE YEAR 2020 2020’s BEST MUSIC MARKETING CAMPAIGNS elcome to Sandbox’s shortlist we had a record number of entries, from labels of the best, most original, and of all sizes from around the world. W most impactful music marketing campaigns of 2020. It’s a celebration of We’re very grateful for everyone who submitted remarkably innovative and creative work across campaigns for consideration – and we hope that a vast array of genres, with many notable in these campaigns you find a wealth of brilliant achievements notched up along the way. -

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him.