Somalia – a Very Special Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Degradation of the Environment As the Cause of Violent Conflict

Mohamed Sahnoun, Algeria. A thematic essay which speaks to Principle 16 on using the Earth Charter to resolve the root causes of violent conflict in Africa Degradation of the Environment as the Cause of Violent Conflict Mohamed Sahnoun has had a distinguished diplo- water and grazing land. Before, the fighting was with sticks; matic career serving as Adviser to the President of now it is with Kalashnikovs. That is the terrible thing about it. Algeria on diplomatic affairs, Deputy Secretary- There is no difference there; they are the same people. General of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), and Deputy Secretary-General of the League of I am often a witness in my work of the linkage between the Arab States in charge of the Arab-Africa dialogue. degradation of the environment and the spread of violent con- He has served as Algeria’s Ambassador to the flicts. We tend to underestimate the impact of degradation of United States, France, Germany, and Morocco, as well as to the United the environment on human security everywhere. Repeated Nations (UN). Mr. Sahnoun is currently Secretary General Kofi Annan’s droughts, land erosion, desertification, and deforestation Special Adviser in the Horn of Africa region. Previously, he served as brought about by climate change and natural disasters compel Special Adviser to the Director General of the United Nations Scientific large groups to move from one area to another, which, in turn, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for the Culture of Peace increases pressure on scarce resources, and provokes strong Programme, Special Envoy of the Secretary-General on the reaction from local populations. -

Preventive Diplomacy and Ethnic Conflict: Possible, Difficult, Necessary

ISSN 1088-2081 Preventive Diplomacy and Ethnic Conflict: Possible, Difficult, Necessary Bruce W. Jentleson University of California, Davis Policy Paper # 27 June 1996 The author and IGCC are grateful to the Pew Charitable Trusts for generous support of this project. Author’s opinions are his own. Copyright © 1996 by the Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation CONTENTS Defining Preventive Diplomacy ........................................................................................5 CONCEPTUAL PARAMETERS FOR A WORKING DEFINITION....................................................6 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN MEASURING SUCCESS AND FAILURE.....................8 The Possibility of Preventive Diplomacy .........................................................................8 THE PURPOSIVE SOURCES OF ETHNIC CONFLICT ..................................................................8 CASE EVIDENCE OF OPPORTUNITIES MISSED........................................................................9 CASE EVIDENCE OF SUCCESSFUL PREVENTIVE DIPLOMACY ...............................................11 SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................12 Possible, but Difficult.......................................................................................................12 EARLY WARNING................................................................................................................12 POLITICAL WILL .................................................................................................................14 -

International Organizations

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY (E.S.A.) Headquarters: 8–10 Rue Mario Nikis, 75738 Paris, CEDEX 15, France phone 011–33–1–5369–7654, fax 011–33–1–5369–7651 Chairman of the Council.—Alain Bensoussan (France). Director General.—Antonio Rodota (Italy). Member Countries: Austria Germany Portugal Belgium Ireland Spain Denmark Italy Sweden Finland Netherlands Switzerland France Norway United Kingdom Cooperative Agreement.—Canada. European Space Operations Center (E.S.O.C.), Robert Bosch-Strasse 5, 61, Darmstadt, Germany, phone 011–49–6151–900, telex: 419453, fax 011–49–6151–90495. European Space Research and Technology Center (E.S.T.E.C.), Keplerlaan 1, 2201, AZ Noordwijk, Zh, Netherlands, phone 011–31–71–565–6565; Telex: 844–39098, fax 011–31–71–565–6040. Information Retrieval Service (E.S.R.I.N.), Via Galileo Galilei, Casella Postale 64, 00044 Frascati, Italy. Phone, 011–39–6–94–18–01; Telex: 610637, fax 011–39–94–180361. Washington Office (E.S.A.), Suite 7800, 955 L’Enfant Plaza SW. 20024. Head of Office.—I.W. Pryke, 488–4158, fax: (202) 488–4930, [email protected]. INTER-AMERICAN DEFENSE BOARD 2600 16th Street 20441, phone 939–6041, fax 939–6620 Chairman.—MG Carl H. Freeman, U.S. Army. Vice Chairman.—Brigadier General Jose´ Mayo, Air Force, Paraguay. Secretary.—Col. Robert P. Warrick, U.S. Air Force. Vice Secretary.—CDR Carlos Luis Rivera Cordova, Navy. Deputy Secretary for Administration.—LTC Frederick J. Holland, U.S. Army. Conference.—Maj. Robert L. Larson, U.S. Army. Finance.—Maj. Stephen D. Zacharczyk, U.S. Army. Information Management.—Maj. -

Earth Charter Values and Principles for a Sustainable Future

The Earth Charter Values and Principles for a Sustainable Future Why is the Earth Charter important? and development of the document reflects the progress of the worldwide dialogue on the Earth At a time when major changes in how we think Charter. Beginning with the Benchmark Draft and live are urgently needed, the Earth Charter issued by the Commission following the Rio+5 challenges us to examine our values and to Forum in Rio de Janeiro, drafts of the Earth choose a better way. It calls on us to search for Charter were circulated internationally as part of common ground in the midst of our diversity and the consultation process. Meeting at the to embrace a new ethical vision that is shared by UNESCO Headquarters in Paris in March, 2000, growing numbers of people in many nations and the Commission approved a final version of the cultures throughout the world. Earth Charter. What is the history of the Earth What are the sources of Earth Charter? Charter values? In 1987 the United Nations World Commission on Together with the Earth Charter consultation Environment and Development issued a call for process, the most important influences shaping creation of a new charter that would set forth fun- the ideas and values in the Earth Charter are con- damental principles for sustainable development. temporary science, international law, the teach- The drafting of an Earth Charter was part of the he Earth Charter is a ings of indigenous peoples, the wisdom of the unfinished business of the 1992 Rio Earth world’s great religions and philosophical tradi- Tdeclaration of fundamental Summit. -

Toward a Great Ethics Transition: the Earth Charter at Twenty Brendan Mackey

Toward a Great Ethics Transition: The Earth Charter at Twenty Brendan Mackey Opening Comment for a GTN Discussion January 2, 2020 *Pre-Release: Not for Distribution* Why a Common Ethical Framework Seventy-two years ago, in 1948, the newly created United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. With a catastrophic war fresh in people’s memory, the recognition of the “inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family” augured a sound ethical foundation for a hopeful future. Although the subsequent decades saw the tension and tumult of the Cold War (and some hot ones), a new internationalism was also on the upswing. Since then, a profusion of declarations and charters have sought to establish normative ethics based on universal values and principles presumed to be shared by all people, nations, and cultures. This includes, among others, the Stockholm Declaration (1972), the World Charter for Nature (1982), the Rio Declaration (1992), the Earth Charter (2000), the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), the Draft Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth (2010), and the Principles of Climate Justice (2011). The proposition that there are universal ethical values and principles shared among all the Peoples of the world remains contested and, in some respects, rightly so. Post-modernist critics warn us that a single idea universally applied can ignore local contexts and swallow up the diverse values that reside in the richly textured tapestry that is the hallmark of human society and our biocultural relationships. -

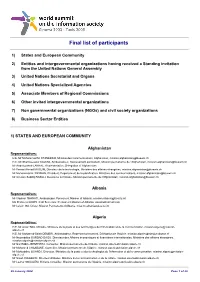

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

The UN Security Council and the Responsibility to Protect

The UN Security Council and the Responsibility to Protect FAVORITA PapeRs 01/2010 01/2010 S The UN Security Council PAPER A and the Responsibility to Protect FAVORIT Policy, Process, and Practice DA 39th IPI VIenna SemInar BN 978-3-902021-67-0 s I "FAVORITA PAPERS" OF THE DIPLOMATIC ACADEMY OF VIENNA The ‘Favorita Papers’ series is intended to complement the academic training for international careers which is the core activity of the Diplomatic Academy. It reflects the expanding conference and public lectures programme of the Academy by publishing substantive conference reports on issues that are of particular relevance to the understanding of contemporary international problems and to the training for careers in diplomacy, international public service and business. The series was named ‘Favorita Papers’ after the original designation of the DA’s home, the imperial summer residence ‘Favorita’ donated by Empress Maria Theresia to the ‘Theresianische Akademie’ in 1749. Contributions to this series come from academics and practitioners actively engaged in the study, teaching and practice of international affairs. All papers reflect the views of the author. THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT: POLICY, PROCESS, AND PRACTICE 39th IPI Vienna Seminar Diplomatic Academy of Vienna Favorita Papers 01/2010 Edited by: Hans Winkler (DA), Terje Rød-Larsen (IPI), Christoph Mikulaschek (IPI) ISBN 978-3-902021-67-0 ©2010 The Diplomatic Academy of Vienna The Diplomatic Academy of Vienna is one of Europe’s leading schools for post-graduate studies in international relations and European affairs. It prepares young university graduates for the present-day requirements of successful international careers in diplomacy, public administration and business. -

Determinants of Success of the United Nations Peace Operations in a Stateless Terrain: the Lessons of Sierra Leone and Somalia

DETERMINANTS OF SUCCESS OF THE UNITED NATIONS PEACE OPERATIONS IN A STATELESS TERRAIN: THE LESSONS OF SIERRA LEONE AND SOMALIA By Olga Kuzmina Submitted to Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Political Science Supervisor: Professor András Bozóki CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary (2016) Abstract The present thesis has pursued the goal of making an empirical contribution to the literature on the United Nations peacekeeping, and, in particular, on the determinants of success in the United Nations peace operations. It is assumed that there is a set of necessary factors, apart from conflict pre- conditions, that are jointly sufficient for a successful multidimensional UN peace operation. In order to assess success in UN peacekeeping, the complex formula, combining the completion of mission’s mandate, progress in achieving a stable political solution, and providing a secure environment for civilians and the UN personnel, was elaborated. The study focuses on two cases of the UN involvement in civil wars: The United Nations Peacekeeping Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM) and the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL). Building on existing scholarly literature, UN documents, press materials, interviews with senior UN officials, digital materials and statistical data, the factors, attributed to successful peace operations by scholars, are tested in a comparative perspective. The study concludes that necessary factors that are jointly sufficient for a successful UN peace operation are: a group of administrative factors (competent leadership and personnel, and clear command structures; internal and external co-ordination; sufficient duration; communications and logistical support), a group of local factors (sense of security of the parties; ownership; credibility of UN forces), and addressing real causes of the conflict, moderate UNSC interest, and organizational learning. -

The Responsibility to Protect: Locating Norm Entrepreneurship

This is a repository copy of The Responsibility to Protect: Locating Norm Entrepreneurship. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/177566/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Stefan, CG orcid.org/0000-0002-0706-2082 (2021) The Responsibility to Protect: Locating Norm Entrepreneurship. Ethics & International Affairs, 35 (2). pp. 197-211. ISSN 0892- 6794 https://doi.org/10.1017/s0892679421000216 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Dear Contributor, Enclosed please find page proofs for your article scheduled to be published in Ethics & International Affairs. Please follow these procedures: Please list the corrections in an email, citing page number, paragraph number, and line number. Send the corrections to Katrina Swartz ([email protected]) and Adam Read-Brown ([email protected]). You are responsible for correcting your proofs. Errors not found may appear in the published journal. The proof is sent to you for correction of typographical errors only. -

Is Humanitarianism Part of the Problem? Nine Theses

Is Humanitarianism Part of the Problem? Nine Theses Roberto Belloni 2005-03 April 2005 CITATION AND REPRODUCTION This document appears as Discussion Paper 2005-03 of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. BCSIA Discussion Papers are works in progress. Comments are welcome and may be directed to the author at [email protected]. This paper may be cited as: Roberto Belloni. “Is Humanitarianism Part of the Problem? Nine Theses.” BCSIA Discussion Paper 2005-03, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, April 2005. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and publication does not imply their endorsement by BCSIA and Harvard University. This paper may be reproduced for personal and classroom use. Any other reproduction is not permitted without written permission of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. To obtain more information, please contact: Sarah B. Buckley, International Security Program, 79 JFK Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, telephone (617) 495-1914; facsimile (617) 496-4403; email [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Roberto Belloni is currently a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) at the School of Politics and International Studies at Queens University, Belfast, Northern Ireland. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Denver, Colorado, and between 2002–2004 was a Research Fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and the Program on Intra-state Conflict at Harvard University. He has extensive work and research experience in southeastern Europe, and he is currently completing a book manuscript tentatively titled “Building Peace in Bosnia.” TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Nine Theses 1. -

The Responsibility to Protect: from Document to Doctrine - but What of Implementation

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2006 The Responsibility to Protect: From Document to Doctrine - But What of Implementation Rebecca Hamilton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT: FROM DOCUMENT TO DOC- TRINE-BUT WHAT OF IMPLEMENTATION? BACKGROUND Between 1990 and 1994, the United Nations Security Council passed twice as many resolutions as had been passed in the entire history of the United Nations ("U.N."),' as the notion of what constituted a "threat to international peace and security" under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter was expanded to include humanitarian concerns. 2 The decade following the end of the Cold War saw Security Council resolutions authorizing Chapter VII interventions in Somalia, 3 Liberia,4 Rwanda, 5 Haiti,6 Sierra Leone, 7 and Kosovo. 8 This led many to posit the emergence of a challenge to the assumed inviolability of state sovereignty.9 However, the interventions of the 1990s were inconsistent, lacking any coherent theory with which to justify the infringement of sovereignty in each case. 10 In his Millennium Report, Secretary-General Kofi Annan issued a challenge: "[I1f humanitarian intervention is, indeed, an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica-to gross and systematic violations of human rights that offend every precept of our common humanity?"'"I In December 2001, the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty ("ICISS") published its response in a report entitled The Re- sponsibility to Protect ("R2P"). -

Brookings Corrected 041904.Qxd

Global Governance Initiative Annual Report 2004 Global Governance Initiative Annual Report 2004 The views expressed in the articles in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Economic Forum. © 2004 World Economic Forum ISBN 0-9741108-3-3 Designed, edited and produced by Communications Development Incorporated, Washington, D.C., with Grundy Northedge, London Global Governance Initiative Developed in partnership with Expert group chairs and members Peace and security Mahmoud Fathalla, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chair: Gareth Evans, President, International Crisis Group (Australia) Assiut University (Egypt) Ellen Laipson, President, Henry L. Stimson Center (USA) Cesar Victora, Professor of Epidemiology, Federal University of Mohamed Sahnoun, Special Representative of the UN Pelotas (Brazil) Secretary-General for the Sudan (Algeria) Rick Steketee, Chief, Malaria Epidemiology Branch, Centers for Andrew Mack, Director, Human Security Centre, University of Disease Control and Prevention (USA) British Columbia (Australia) Tom Coates, Professor of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School Jane Nelson, Director, Business Leadership and Strategy, Prince of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles (USA) of Wales International Business Leaders Forum, and Fellow, Center for Business and Government, Harvard University (UK) Ramesh Thakur, Senior Vice Rector for Peace and Governance, Human rights United Nations University (India) Chair: Robert Archer, Executive Director, International Council on Human Rights