Ronald A. Beghetto Bharath Sriraman Editors Cross Disciplinary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View the Conference Program

11TH BIENNIAL INTERNATIONAL MEANING CONFERENCE International Network on I N PERSONAL P M MEANING VIRTUAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM | AUG 6 – 8, 2021 FROM VULNERABILITY TO RESILIENCE & WELLBEING DURING THE PANDEMIC: ADVANCES IN EXISTENTIAL POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY (PP2.0) 11TH BIENNIAL INTERNATIONAL MEANING CONFERENCE (INPM 2021) Sponsored by Conference Program | 1 11TH BIENNIAL INTERNATIONAL MEANING CONFERENCE MISSION STATEMENT AND VISION The International Network on Personal Meaning (INPM) is dedicated to advancing the well-being of individuals and society through research, education, and positive applied psychology with a focus on the universal human question for meaning and purpose. WHO WE ARE The INPM is an international, multidisciplinary, learned society founded by Paul T. P. Wong in 1998 to expand the legacy of Dr. Viktor Frankl. It was incorporated as a non-profit organization with the Federal Government of Canada in 2001. The INPM is governed by a Board of Directors. The professional arm of the INPM is the International Society for Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy. OBJECTIVES AND ACTIVITIES 1. To advance scientific research of meaning and the movement of second wave positive psychology (PP 2.0) through Biennial International Meaning Conferences and the International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology. 2. To advance the scholarship and practice of meaning-centered approach to coaching, counselling, psychotherapy, management, and education through Summer Institutes, Meaning Conferences, certification programs, and our website (www.meaning.ca). 3. To educate the public regarding the broad application of the principles of meaningful living based on research through the Positive Living Newsletter, and the Meaningful Living Meetup Groups, website, and social media. All the activities of the INPM are funded entirely by membership dues, donations, and revenue from teaching and conference events. -

Kaufman-CV.Pdf

Scott Barry Kaufman, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Address: New York University Department of Psychology 6 Washington Place, Room 158 New York, New York 10003 Email: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.scottbarrykaufman.com EDUCATION Yale University (New Haven, CT) Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology, 2009 M. Phil & M.S. in Cognitive Psychology, 2007 Dissertation Title: Beyond general intelligence: The dual-process theory of human intelligence Advisors: Jeremy R. Gray & Robert J. Sternberg University of Cambridge (Cambridge, UK) M. Phil in Experimental Psychology, 2005 Gates Cambridge Scholar Thesis Title: The relationship between intelligence and working memory: An individual differences approach Advisor: Nicholas J. Mackintosh Carnegie Mellon University (Pittsburgh, PA) B.S., Psychology (Honors) and Human Computer Interaction, 2003 Minor: Music Performance Honors Thesis Title: The relationship between expertise and the performance of traditional vs. music series completion problems Mentors: Anne Fay, Herbert Simon, Randy Paunch EMPLOYMENT Fall 2010-ongoing Adjunct Assistant Professor of Psychology Department of Psychology New York University Fall 2009-Fall 2010 Post-doctoral fellow Center Leo Apostel for Interdisciplinary Studies Free University of Brussels (Belgium) AFFILIATIONS Fall 2009-Fall 2010 Visiting Scholar Department of Psychology New York University SERVICE Co-founder, The Creativity Post (http://creativitypost.com) (2011-ongoing) Chief Science Advisor, The Future Project (http://thefutureproject.org) (2011- ongoing) Student Representative, (2005-2007), Division 10, American Psychological Association Society for the Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts TRAINING Pre-doctoral fellow, The Edward Zigler Center in Child Development and Social Policy, School of Medicine, Yale University (2005-2008) GRANTS AND AWARDS 2012 Mensa Excellence in Research Award 2011 Daniel E. -

Angela Duckworth Researcher Co-Founder of the Character Lab; Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania

Angela Duckworth Researcher Co-Founder of the Character Lab; Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania Angela Duckworth is a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and a 2013 MacArthur fellow. She is also the founder and scientific director of the Character Lab, a nonprofit whose mission is to advance the science and practice of character development. Angela studies grit and self-control, two attributes that are distinct from IQ and yet powerfully predict success and well-being. Previously, Angela founded a summer school for low-income children that was profiled as a Harvard Kennedy School case study and, in 2012, celebrated its twentieth anniversary. She has also been a McKinsey management consultant and a math and science teacher. Angela completed her undergraduate degree in Advanced Studies Neurobiology at Harvard, an MSc in Neuroscience from Oxford University, and a PhD in Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. Angela’s first book,Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, debuted May 3, 2016. w: http://angeladuckworth.com Susan Engel Researcher Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Founding Director of the Program in Teaching at Williams College Susan Engel is Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Founding Director of the Program in Teaching at Williams College. Her research interests include the development of curiosity, children’s narratives, play, and more generally, teaching and learning. Her current research looks at whether students learn to think well in college. Her scholarly work has appeared -

[email protected]

Scott Barry Kaufman, Ph.D. Positive Psychology Center University of Pennsylvania 3701 Market St., Suite 217 Philadelphia, PA 19104 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Yale University (New Haven, CT) Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology, 2009 M. Phil & M.S. in Cognitive Psychology, 2007 Dissertation Title: Beyond general intelligence: The dual-process theory of human intelligence Advisors: Jeremy R. Gray & Robert J. Sternberg University of Cambridge (Cambridge, UK) M. Phil in Experimental Psychology, 2005 Gates Cambridge Scholar Thesis Title: The relationship between intelligence and working memory: An individual differences approach Advisor: Nicholas J. Mackintosh Carnegie Mellon University (Pittsburgh, PA) B.S., Psychology (Honors) and Human Computer Interaction, 2003 Minor: Music Performance Honors Thesis Title: The relationship between expertise and the performance of traditional vs. music series completion problems Mentors: Anne Fay, Herbert Simon, Randy Paunch Employment May 2014-ongoing Scientific Director The Imagination Institute Positive Psychology Center University of Pennsylvania (http://imagination-institute.org) Fall 2010-Spring-2013 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Psychology Department of Psychology New York University Fall 2009-Fall 2010 Post-doctoral fellow Center Leo Apostel for Interdisciplinary Studies Free University of Brussels (Belgium) Training Pre-doctoral fellow, The Edward Zigler Center in Child Development and Social Policy, School of Medicine, Yale University (2005-2008) Grants and Awards 2014 (in preparation) Imagination in Action: Documenting in Real Time Very Imaginative Projects of Very Imaginative People; Templeton Religion Trust (Proposed Amount: $5,700,000) 2014 (awarded) Advancing the Science of Imagination: Toward an “Imagination Quotient”; John Templeton Foundation ($5,647,094) 2012 Mensa Excellence in Research Award 2011 Daniel E. -

LEARNING& Thebrain®

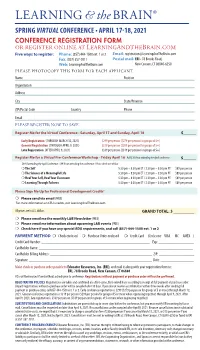

LEARNING & the BRAIN® SPRING VIRTUAL CONFERENCE • APRIL 17-18, 2021 CONFERENCE REGISTRATION FORM OR REGISTER ONLINE AT LEARNINGANDTHEBRAIN.COM Five ways to register: Phone: (857) 444-1500 ext. 1 or 2 Email: [email protected] Fax: (857) 357-7011 Postal mail: ERI • 78 Brooks Road, Web: LearningAndTheBrain.com New Canaan, CT 06840-6250 PLEASE PHOTOCOPY THIS FORM FOR EACH APPLICANT. Name Position Organization Address City State/Province ZIP/Postal Code Country Phone Email PLEASE REGISTER NOW TO SAVE. Register Me for the Virtual Conference - Saturday, April 17 and Sunday, April 18 $______ Early Registration (THROUGH MARCH 12, 2021) $299 per person ($279 per person for groups of 5+) General Registration (THROUGH APRIL 9, 2021) $319 per person ($299 per person for groups of 5+) Late Registration (AFTER APRIL 9, 2021) $339 per person ($319 per person for groups of 5+) Register Me for a Virtual Pre-Conference Workshop - Friday April 16 Add $10 if not attending the April conference $______ $89 if attending the April Conference. $99 if not attending the conference. Please check one of four: m The Self 5:30 pm – 8:30 pm ET / 2:30 pm – 5:30 pm PT $89 per person m The Science of a Meaningful Life 5:30 pm – 8:30 pm ET / 2:30 pm – 5:30 pm PT $89 per person m Heal Your Self, Heal Your Classroom 5:30 pm – 8:30 pm ET / 2:30 pm – 5:30 pm PT $89 per person m Learning Through Failures 5:30 pm – 8:30 pm ET / 2:30 pm – 5:30 pm PT $89 per person Please Sign Me Up for Professional Development Credits* m Please send via email (FREE) *For more information on CEUs credits, visit LearningAndTheBrain.com. -

Scott Barry Kaufman Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51806-2 - The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Scott Barry Kaufman Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence This volume provides the most comprehensive and up-to-date compendium of theory and research in the field of human intelligence. The 42 chapters are written by world-renowned experts, each in his or her respective field, and collectively, the chapters cover the full range of topics of contemporary interest in the study of intelligence. The handbook is divided into nine parts: Part I covers intelligence and its measurement; Part II deals with the development of intelligence; Part III discusses intelligence and group differences; Part IV concerns the biology of intelligence; Part V is about intelligence and information processing; Part VI discusses different kinds of intelligence; Part VII covers intelligence and society; Part VIII concerns intelligence in relation to allied constructs; and Part IX is the concluding chapter, which reflects on where the field is currently and where it still needs to go. Robert J. Sternberg is provost and senior vice president and professor of psychology at Oklahoma State University. He was previously dean of the School of Arts and Sciences and professor of psychology and education at Tufts University. His PhD is from Stanford and he holds 11 honorary doctorates. Sternberg is president of the International Association for Cognitive Education and Psychology and president-elect of the Federation of Associations of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. He was the 2003 president of the American Psychological Association and was the president of the Eastern Psychological Association.