What Does It Mean That PRIMES Is in P? Popularization and Distortion Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

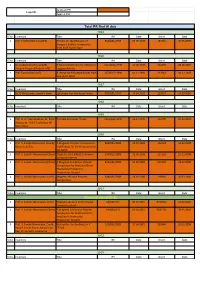

Patent Filed, Commercialized & Granted Data

Granted IPR Legends Applied IPR Total IPR filed till date 1995 S.No. Inventors Title IPA Date Grant Date 1 Prof. P K Bhattacharya (ChE) Process for the Recovery of 814/DEL/1995 03.05.1995 189310 05.05.2005 Inorganic Sodium Compounds from Kraft Black Liquor 1996 S.No. Inventors Title IPA Date Grant Date 1 Dr. Sudipta Mukherjee (ME), A Novel Attachment for Affixing to 1321/DEL/1996 12.08.1996 192495 28.10.2005 Anupam Nagory (Student, ME) Luggage Articles 2 Prof. Kunal Ghosh (AE) A Device for Extracting Power from 2673/DEL/1996 02.12.1996 212643 10.12.2007 to-and-fro Wind 1997 S.No. Inventors Title IPA Date Grant Date 1 Dr. D Manjunath, Jayesh V Shah Split-table Atm Multicast Switch 983/DEL/1997 17.04.1997 233357 29.03.2009 1998 S.No. Inventors Title IPA Date Grant Date 1999 1 Prof. K. A. Padmanabhan, Dr. Rajat Portable Computer Prinet 1521/DEL/1999 06.12.1999 212999 20.12.2007 Moona, Mr. Rohit Toshniwal, Mr. Bipul Parua 2000 S.No. Inventors Title IPA Date Grant Date 1 Prof. S. SundarManoharan (Chem), A Magnetic Polymer Composition 858/DEL/2000 22.09.2000 216744 24.03.2008 Manju Lata Rao and Process for the Preparation of the Same 2 Prof. S. Sundar Manoharan (Chem) Magnetic Cro2 – Polymer 933/DEL/2000 22.09.2000 217159 27.03.2008 Composite Blends 3 Prof. S. Sundar Manoharan (Chem) A Magneto Conductive Polymer 859/DEL/2000 22.09.2000 216743 19.03.2008 Compositon for Read and Write Head and a Process for Preparation Thereof 4 Prof. -

Poly-Time Blackbox Identity Testing for Sum of Log-Variate Constant-Width Roabps

Poly-time blackbox identity testing for sum of log-variate constant-width ROABPs Pranav Bisht ∗ Nitin Saxena † Abstract Blackbox polynomial identity testing (PIT) affords ‘extreme variable-bootstrapping’ (Agrawal et al, STOC’18; PNAS’19; Guo et al, FOCS’19). This motivates us to study log-variate read-once oblivious algebraic branching programs (ROABP). We restrict width of ROABP to a constant and study the more general sum-of-ROABPs model. We give the first poly(s)-time blackbox PIT for sum of constant-many, size-s, O(log s)-variate constant-width ROABPs. The previous best for this model was quasi-polynomial time (Gurjar et al, CCC’15; CC’16) which is comparable to brute-force in the log-variate setting. Also, we handle unbounded-many such ROABPs if each ROABP computes a homogeneous polynomial. Our new techniques comprise– (1) an ROABP computing a homogeneous polynomial can be made syntactically homogeneous in the same width; and (2) overcome the hurdle of unknown variable order in sum-of-ROABPs in the log-variate setting (over any field). 2012 ACM CCS concept: Theory of computation– Algebraic complexity theory, Fixed parameter tractability, Pseudorandomness and derandomization; Computing methodologies– Algebraic algorithms; Mathematics of computing– Combinatoric problems. Keywords: identity test, hitting-set, ROABP, blackbox, log variate, width, diagonal, derandom- ization, homogeneous, sparsity. 1 Introduction Polynomial Identity Testing (PIT) is the problem of testing whether a given multivariate polynomial is identically zero or not. The input polynomial to be tested is usually given in a compact representation– like an algebraic circuit or an algebraic branching program (ABP). -

Indian Roots of Cryptography

Algologic Technical Report # 2/2013 The Indian roots of cryptography S. Parthasarathy [email protected] Ref.: newcryptoroots.tex Ver. code: 20190123a Keywords : Alice, Bob, Sita, Rama, Vatsyayana, Kamasutra, Hemachan- dra, Fibonacci, Hindu, Arab, Numeral, Ramanujan, Agarwal, AKS, IITK Abstract This note is a sequel to my article [2] about the dramatis personae of cryptography. The article, provoked a world-wide reaction. In fact, a related Google search resulted in over 6 million hits, making me a kind of celebrity ! For those who care to be more reasonable and logical, here is some more evidence to strengthen the proposal I made earlier in my article about Sita and Rama. 1 The Indian roots of cryptography The article [2] about Alice and Bob, talks about the dramatis personae of cryptography, and proposes a much more meaningful alternative. The au- thor came across many situations when contributions by India are unfairly understated or ignored completely by the cryptography community. We take a quick look at some of them. One remarkable exception is the book by Kim Plofker [15], a well-documented book which is free of bias and exaggeration. Most books on cryptography invariably include the Caesar’s cipher as an example of substitution cipher. It is strange that they all ignore, or are unaware of another substitution cipher which was in use a few centuries before Caesar’s cipher. According to [1] Cryptography is recommended in the Kama Sutra (ca 400 BCE) as a way for lovers to communicate without inconvenient discovery. 1 The Signal Corps Association [3], gives an interesting explanation of the kama sutra cipher. -

Lipics-CCC-2021-11.Pdf (1

Deterministic Identity Testing Paradigms for Bounded Top-Fanin Depth-4 Circuits Pranjal Dutta # Ñ Chennai Mathematical Institute, India Department of Computer Science & Engineering, IIT Kanpur, India Prateek Dwivedi # Ñ Department of Computer Science & Engineering, IIT Kanpur, India Nitin Saxena # Ñ Department of Computer Science & Engineering, IIT Kanpur, India Abstract Polynomial Identity Testing (PIT) is a fundamental computational problem. The famous depth-4 reduction (Agrawal & Vinay, FOCS’08) has made PIT for depth-4 circuits, an enticing pursuit. The largely open special-cases of sum-product-of-sum-of-univariates (Σ[k]ΠΣ∧) and sum-product- of-constant-degree-polynomials (Σ[k]ΠΣΠ[δ]), for constants k, δ, have been a source of many great ideas in the last two decades. For eg. depth-3 ideas (Dvir & Shpilka, STOC’05; Kayal & Saxena, CCC’06; Saxena & Seshadhri, FOCS’10, STOC’11); depth-4 ideas (Beecken,Mittmann & Saxena, ICALP’11; Saha,Saxena & Saptharishi, Comput.Compl.’13; Forbes, FOCS’15; Kumar & Saraf, CCC’16); geometric Sylvester-Gallai ideas (Kayal & Saraf, FOCS’09; Shpilka, STOC’19; Peleg & Shpilka, CCC’20, STOC’21). We solve two of the basic underlying open problems in this work. We give the first polynomial-time PIT for Σ[k]ΠΣ∧. Further, we give the first quasipolynomial time blackbox PIT for both Σ[k]ΠΣ∧ and Σ[k]ΠΣΠ[δ]. No subexponential time algorithm was known prior to this work (even if k = δ = 3). A key technical ingredient in all the three algorithms is how the logarithmic derivative, and its power-series, modify the top Π-gate to ∧. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Theory of computation → Algebraic complexity theory Keywords and phrases Polynomial identity testing, hitting set, depth-4 circuits Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/LIPIcs.CCC.2021.11 Funding Pranjal Dutta: Google Ph. -

Classifying Polynomials and Identity Testing

Classifying polynomials and identity testing MANINDRA AGRAWAL1,∗ and RAMPRASAD SAPTHARISHI2 1Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India. 2Chennai Mathematical Institute, and Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India. e-mail: [email protected] One of the fundamental problems of computational algebra is to classify polynomials according to the hardness of computing them. Recently, this problem has been related to another important problem: Polynomial identity testing. Informally, the problem is to decide if a certain succinct representation of a polynomial is zero or not. This problem has been extensively studied owing to its connections with various areas in theoretical computer science. Several efficient randomized algorithms have been proposed for the identity testing problem over the last few decades but an efficient deterministic algorithm is yet to be discovered. It is known that such an algorithm will imply hardness of computing an explicit polynomial. In the last few years, progress has been made in designing deterministic algorithms for restricted circuits, and also in understanding why the problem is hard even for small depth. In this article, we survey important results for the polynomial identity testing problem and its connection with classification of polynomials. 1. Introduction its simplicity. For example, consider the polyno- mials The interplay between mathematics and computer ··· science demands algorithmic approaches to vari- (1 + x1)(1 + x2) (1 + xn) ous algebraic constructions. The area of computa- and tional algebra addresses precisely this. The most fundamental objects in algebra are polynomials x1x2 ···xn. and it is a natural idea to classify the polyno- mials according to their ‘simplicity’. The algorith- The former has 2n − 1 more terms than the later, mic approach suggests that the simple polynomials however, both are almost equally easy to describe are those that can be computed easily. -

Honours Number Theory : the Agrawal-Kayal-Saxena Primality Test

MATH 377 - Honours Number Theory : The Agrawal-Kayal-Saxena Primality Test Azeem Hussain May 4, 2013 1 Introduction Whether or not a number is prime is one of its most fundamental properties. Many branches of pure mathematics rely heavily on numbers being prime. Prime numbers are in some sense the purest. Irreducible (over Z), they are the building blocks of all other numbers. And yet, determining if a number is prime is not an easy task, certainly not if the number is very large. There are various algorithms for primality testing. For example, the Sieve of Eratos- thenes, developed in Ancient Greece. Reliable, it works on all inputs. The problem is that it takes very long. The running time is exponential in the size of the input. Miller devised a test for primality that runs in polynomial time [1]. The problem is that is assumes the extended Riemann hypothesis. Rabin adapted Miller’s test to yield a reliable polynomial time primality test, the Miller- Rabin test [2]. This test works well in practice. The problem is that the test is randomized and not guaranteed to work. However, the probability or error can be made miniscule by successive repetition. Nevertheless, to the mathematician, this leaves something to be desired. Ideally, the test will produce a certificate, a proof that the number is prime. This test can only say that the number is “probably prime.” Most primality tests fall into one of these three categories. Either they scale exponen- tially in time with the input, they rely on some conjecture, or they are randomized. -

CV (Nitin Saxena)

CV (Nitin Saxena) Personal Information Name: NITIN SAXENA Address: RM203, Department of CSE, IIT Kanpur, Kanpur-208016 ; +91-512-679-7588 E-address: [email protected] ; https://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/users/nitin/ Date and place of birth: 3rd MAY 1981, Allahabad/Prayagraj, India Nationality: INDIA Gender: M S Degree Subject Year University Additional No Particulars 1 B.Tech. Computer 2002 Indian Institute of Thesis: Towards a Science & Technology deterministic polynomial- Engineering, Kanpur time primality test (Won Algebra, the best BTech CSE Number theory Project Award 2002) 2 Ph.D. Computer 2006 Indian Institute of Thesis: Morphisms of Science & Technology Rings and Applications to Engineering, Kanpur Complexity (Won Algebra, Outstanding PhD Student Number theory Award of IBM India Research Lab 2005) Guide: Manindra Agrawal 3 Post-Doc Mathematics, 2006- CWI (Centrum Host: Prof.dr.Harry Research Informatics, 08 voor Wiskunde en Buhrman Quantum Informatica) complexity Amsterdam, Netherlands Date of joining the Institution (Designation & Scale): 05-Nov-2018, Professor (CSE), AcadLevel=14A, Basic=173900/- Positions held earlier (in chronological order): S Period Place of Employment Designation No 1 Jul'02- CSE, IIT Kanpur Infosys PhDFellow Jul'06 2 Sep'03- CS, Princeton University, USA Visiting Student Research Aug'04 Collaborator 3 Sep'04- CS, National University of Singapore Visiting Scholar Jun'05 4 Sep'06- CWI Amsterdam, The Netherlands Scientific Researcher Mar'08 5 Apr'08- Hausdorff Center for Mathematics, Professor W2, Mar'13 University of Bonn, Germany BonnJuniorFellow 6 Dec'14 UPMC Paris-6, France Visiting Professor 7 Aug'18- Chennai Mathematical Institute, H1, Adjunct Professor Jul'21 SIPCOT IT Park, Chennai. -

Chennai Mathematical Institute Annual Report 2011 - 2012 75 76 Chennai Mathematical Institute

Chennai Mathematical Institute Annual Report 2011 - 2012 H1, SIPCOT IT Park Padur Post, Siruseri, Tamilnadu 603 103. India. Chennai Mathematical Institute H1, SIPCOT IT Park Padur Post, Siruseri, Tamilnadu 603 103. India. Tel: +91-44-2747 0226, 2747 0227 2747 0228, 2747 0229, +91-44-3298 3441 - 3442 Fax: +91-44-2747 0225 WWW: http://www.cmi.ac.in Design and Printing by: Balan Achchagam, Chennai 600 058 Contents 01. Preface ....................................................................................................................... 5 02. Board of Trustees ..................................................................................................... 8 03. Governing Council ................................................................................................... 9 04. Research Advisory Committee ..............................................................................10 05. Academic Council ...................................................................................................11 06. Boards of Studies ....................................................................................................12 07. Institute Members .................................................................................................13 08. Faculty Profiles .......................................................................................................16 09. Awards ....................................................................................................................26 10. Research Activities -

Chennai Mathematical Institute Annual Report 2009 - 2010 75 76 Chennai Mathematical Institute

Chennai Mathematical Institute Annual Report 2009 - 2010 H1, SIPCOT IT Park Padur Post, Siruseri, Tamilnadu 603 103. India. Chennai Mathematical Institute H1, SIPCOT IT Park Padur Post, Siruseri, Tamilnadu 603 103. India. Tel: +91-44-2747 0226 - 0229 +91-44-3298 3441 - 3442 Fax: +91-44-2747 0225 WWW: http://www.cmi.ac.in Design and Printing by: Balan Achchagam, Chennai 600 058 Contents 1. Preface ................................................................................................................... 5 2. Board of Trustees ................................................................................................. 9 3. Governing Council ............................................................................................. 10 4. Research Advisory Committee .......................................................................... 11 5. Academic Council ............................................................................................... 12 6. Boards of Studies ................................................................................................ 13 7. Institute Members ............................................................................................. 14 8. Faculty Profiles ................................................................................................... 17 9. Awards ................................................................................................................. 25 10. Research Activities ............................................................................................ -

Lower-Bounding the Sum of 4Th-Powers of Univariates Leads to Derandomization and Hardness

Lower-bounding the sum of 4th-powers of univariates leads to derandomization and hardness Pranjal Dutta ∗ Nitin Saxena † Abstract We study the sum of fourth-powers (SO4) model to compute univariate polynomials over F = Q. We conjecture : the univariate polynomial (x + 1)d when written as a sum of o(d)-many fourth-powers requires W(d) distinct monomials. We show that the conjecture puts blackbox-PIT (polynomial identity testing) in P; and proves VP 6= VNP (under Gen- eralized Riemann Hypothesis). Thus, studying very simple polynomials, in very simple computational models, suffices to solve the major questions of algebraic complexity theory. Recently, (Dutta et al. , 2020), demonstrated such a connection for the sum of 25th-powers model. Our work optimizes the exponent (from 25 to 4). We achieve this by employing a new ‘CNF’ normal-form, for general circuits, that is highly specialized towards SO4 expression. Basically, it ‘reduces’ the intermediate degrees to 1/3rd before invoking the conjecture. 2012 ACM CCS concept: Theory of computation - Algebraic complexity theory, Problems, reduc- tions and completeness, Pseudorandomness and derandomization; Computing methodologies - Algebraic algorithms; Mathematics of computing - Combinatoric problems. Keywords: VP vs VNP,hitting set, circuit, CNF, normal form, univariate polynomial, 4th powers, PIT, lower bound, sparsity, monomials, support, CH, GRH. 1 Introduction An algebraic circuit over a field F is a layered directed acyclic graph that uses field operations f+, ×g and computes a polynomial. It can be thought of as an algebraic analog of boolean circuits. The leaf nodes are labeled with the input variables x1,..., xn and constants from F. -

Constructive Non-Commutative Rank Computation Is in Deterministic Polynomial Time∗

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SZTAKI Publication Repository Constructive Non-Commutative Rank Computation Is in Deterministic Polynomial Time∗ Gábor Ivanyos1, Youming Qiao2, and K Venkata Subrahmanyam3 1 Institute for Computer Science and Control, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary [email protected] 2 Centre for Quantum Software and Information,University of Technology Sydney, Australia [email protected] 3 Chennai Mathematical Institute, Chennai, India [email protected] Abstract Let B be a linear space of matrices over a field F spanned by n × n matrices B1,...,Bm. The non-commutative rank of B is the minimum r ∈ N such that there exists U ≤ Fn satisfying dim(U) − dim(B(U)) ≥ n − r, where B(U) := span(∪i∈[m]Bi(U)). Computing the non-commutative rank generalizes some well-known problems including the bipartite graph maximum matching problem and the linear matroid intersection problem. In this paper we give a deterministic polynomial-time algorithm to compute the non-com- mutative rank over any field F. Prior to our work, such an algorithm was only known over the rational number field Q, a result due to Garg et al, [20]. Our algorithm is constructive and produces a witness certifying the non-commutative rank, a feature that is missing in the algorithm from [20]. Our result is built on techniques which we developed in a previous paper [24], with a new reduction procedure that helps to keep the blow-up parameter small. There are two ways to realize this reduction. -

Convocation Brochure

Brochure Board of Governors Prof. Debajyoti Paul Earth Sciences Shri Koppillil Radhakrishnan Prof. Vimal Kumar Chairperson Economic Sciences Prof. R. M. Hegde Prof. Abhay Karandikar Electrical Engineering Director (Ex-officio Member) Prof. Braj Bhushan Humanities and Social Sciences Prof. Uday Shanker Dixit Prof. B. V. Phani Shri Deepak Ghaisas Industrial and Management Engineering Shri Rakesh Ranjan Prof. Monica Katiyar Prof. Shalabh Materials Science and Engineering Prof. T. N. Singh Prof. Amit Mitra Prof. Goutam Deo Mathematics and Statistics Dr. Mahesh Gupta Prof. Sameer Khandekar Mechanical Engineering Prof. R. Vijaya Key Institute Administrators Physics Prof. Abhay Karandikar Heads of Inter-Disciplinary Programmes Director and Chairperson, Senate Prof. S. Ganesh Prof. Bishakh Bhattacharya Deputy Director Cognitive Science Prof. Achla Misri Raina Prof. Nachiketa Tiwari Dean, Academic Affairs Design Programme Prof. Onkar Dikshit Prof. Rajeev Gupta Dean, Administration Materials Science Programme Prof. Ashish Dutta Prof. Sameer Khandekar Dean, Digital Infrastructure & Automation Nuclear Engineering and Technology Prof. Debasis Kundu Prof. H. Wanare Dean, Faculty Affairs Photonics Science and Engineering Programme Prof. Samit Ray Chaudhuri Dean, Infrastructure and Planning Chairpersons & Conveners of Standing Prof. Yogesh M. Joshi Committees of Senate Dean, International Relations Prof. A. R. Harish Prof. Abhay Karandikar Dean, Research & Development Chairperson, Senate Educational Policy Committee Prof. Jayant K. Singh Prof. Sandeep Sangal Dean, Reasearch & Alumni Chairperson, Senate Curriculum Development and Prof. Siddhartha Panda Monitoring Committee Dean, Students' Affairs Prof. R. Gurunath Shri K. K. Tiwari Convener, Senate Educational Policy Committee Registrar and Secretary, Senate & Board of Prof. Rajesh Srivastava Governors Chairperson, Senate Elections Committee Prof. Abhay Karandikar Heads of Departments Chairperson, Senate Honorary Degree Committee Prof.