25 August 2021 Aperto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: the Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers Daniela Danna

The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: The Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers Daniela Danna How to cite Danna, D. (2018). The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: The Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers. [Italian Sociological Review, 8 (2), 285-308] Retrieved from [http://dx.doi.org/10.13136/isr.v8i2.238] [DOI: 10.13136/isr.v8i2.238] 1. Author information Daniela Danna Department of Social and Political Science, University of Milan, Italy 2. Author e-mail address Daniela Danna E-mail: [email protected] 3. Article accepted for publication Date: February 2018 Additional information about Italian Sociological Review can be found at: About ISR-Editorial Board-Manuscript submission The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: The Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers Daniela Danna* Corresponding author: Daniela Danna E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the political debate on the legal recognition of same-sex couples and same-sex parenthood in Italy. It focuses on written sources such as documents and historiography of the LGBT movement (so called since the time of the World Pride 2000 event in Rome), and a press review covering the years 2013- 2016. The aim of this reconstruction is to show if and how sexual difference, rather important in matters of procreation, has been talked about within this context. The overwhelming majority of same-sex parents in couples are lesbians, but, as will be shown, lesbians have been seldom mentioned in the debate (main source: a press survey). -

Lega Nord and Anti-Immigrationism: the Importance of Hegemony Critique for Social Media Analysis and Protest

International Journal of Communication 12(2018), 3553–3579 1932–8036/20180005 Lega Nord and Anti-Immigrationism: The Importance of Hegemony Critique for Social Media Analysis and Protest CINZIA PADOVANI1 Southern Illinois University Carbondale, USA In this study, I implement Antonio Gramsci’s hegemony critique to analyze the anti- immigration rhetoric promoted by the Italian ultraright party Lega Nord [Northern League]. Specifically, this case study focuses on the discourse that developed on the microblogging site Twitter during the Stop Invasione [Stop Invasion] rally, organized by Matteo Salvini’s party on October 18, 2014, in Milan. I argue that hegemony critique is helpful to investigate political discourse on social media and to theorize the struggle surrounding contentious topics such as immigration. The method, which is multilayered and includes content analysis and interpretative analysis, allows for the exploration of a considerable data corpus but also an in-depth reading of each tweet. The result is a nuanced understanding of the anti-immigration discourse and of the discourse that developed in favor of immigration and in support of a countermarch, which progressive movements organized in response to Lega’s mobilization on the same day in Milan. Keywords: Lega Nord, ultraright media, far-right media, anti-immigrationism, Twitter, critical social media analysis, mobilization, Gramsci, hegemony critique The rise of ultraright movements in Western Europe and the United States is an indication of the continuous crisis of capitalism and neoliberal ideologies. The financial and economic downturn that plagued Europe and North America beginning in late 2008 and the consequent Brussels-imposed austerity in the European Union have exacerbated the rift between the haves and the have-nots. -

Everyday Intolerance- Racist and Xenophic Violence in Italy

Italy H U M A N Everyday Intolerance R I G H T S Racist and Xenophobic Violence in Italy WATCH Everyday Intolerance Racist and Xenophobic Violence in Italy Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-746-9 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org March 2011 ISBN: 1-56432-746-9 Everyday Intolerance Racist and Xenophobic Violence in Italy I. Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations to the Italian Government ............................................................ 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 4 II. Background ................................................................................................................. 5 The Scale of the Problem ................................................................................................. 9 The Impact of the Media ............................................................................................... -

Ricerca.Qxd 21-09-2007 19:38 Pagina 1 Ricerca.Qxd 21-09-2007 19:38 Pagina 2

ricerca.qxd 21-09-2007 19:38 Pagina 1 ricerca.qxd 21-09-2007 19:38 Pagina 2 Tutte le notizie e gli episodi riportati nella presente pubblicazione sono stati tratti da periodici, quotidiani nazionali e locali, da siti internet e dal monitoraggio continuo. ricerca.qxd 21-09-2007 19:38 Pagina 3 SOMMARIO Introduzione pag. 7 Fiamma Tricolore 11 Forza Nuova 21 Fronte Sociale Nazionale 31 Fascismo e Libertà 37 Alleanza Nazionale 41 Lega Nord 47 Il tradizionalismo cattolico 61 Lago di Garda 65 Associazionismo e musica 75 Cronologia delle azioni dei fascisti a Brescia e delle aggressioni 79 ricerca.qxd 21-09-2007 19:38 Pagina 4 ricerca.qxd 21-09-2007 19:38 Pagina 5 Questo lavoro di indagine, frutto di una ricerca a più mani e in continua evoluzione, nasce dall’esigenza forte di reagire ad una situazione nazionale e locale che vede le formazioni neofasciste prendere sempre più spazio nella società ed essere tol- lerate, se non addirittura legittimate, da settori sempre più ampi di istituzioni e opinione pubblica. Il contesto nazionale ci porta ad assistere ad un uso politico della storia, ad un bieco revisionismo che riabilita un passato che il capitale ha gestito e condizionato attraverso l’utilizzo di bombe, morti e incarcerazioni di compagni, verso posizioni che travalicano le parole d’ordine della pacificazione, anche da forze istituzionali di sinistra, per giungere ad una vera e propria legittimazione. Altro motivo che ci ha portato a redigere queste prime linee per un’inchiesta sul neofascismo locale deriva dalla preoccu- pante caratteristica violenta e squadrista che – da sempre – il fascismo porta con sé. -

Sottosegretari Di Stato Presso I Dicasteri

Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Sottosegretario di Stato Paolo Bonaiuti (per l'informazione e l'editoria) Ministeri senza portafoglio Riforme istituzionali e devoluzione Sottosegretari Aldo Brancher Antonio (Nuccio) Carrara Attuazione programma di governo Sottosegretario Giovanni Dell'Elce Funzione pubblica Sottosegretario Learco Saporito Affari regionali Sottosegretari Alberto Gagliardi Luciano Gasperini Rapporti con il Parlamento Sottosegretari Cosimo Ventucci Gianfranco Conte Ministeri con portafoglio Affari esteri Sottosegretari Roberto Antonione Margherita Boniver Alfredo Luigi Mantica Giampaolo Bettamio Giuseppe Drago Interno Sottosegretari Maurizio Balocchi Antonio D'Ali Alfredo Mantovano Michele Saponara Gianpiero D'Alia Giustizia Sottosegretari: Iole Santelli Giuseppe Valentino Luigi Vitali Pasquale Giuliano Economia e Finanze Vice Ministro: Mario Baldassarri Giuseppe Vegas Sottosegretari: Maria Teresa Armosino Manlio Contento Daniele Molgora Michele Vietti Attività produttive Vice Ministro Adolfo Urso Sottosegretari Giuseppe Galati Mario Valducci Roberto Cota Giovan Battista Caligiuri Istruzione, università e ricerca Vice Ministro Guido Possa Giovanni Ricevuto Sottosegretari Valentina Aprea Maria Grazia Siliquini Lavoro e politiche sociali Sottosegretari Alberto Brambilla Maurizio Sacconi Grazia Sestini Pasquale Viespoli Roberto Rosso Francesco Saverio Romano Difesa Sottosegretari Filippo Berselli Francesco Bosi Salvatore Cicu Rosario Giorgio Costa Politiche agricole e forestali Sottosegretari Paolo Scarpa Bonazza Buora -

Firmatari Appello 25Aprile.Pdf

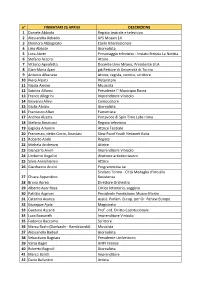

n° FIRMATARI 25 APRILE DESCRIZIONE 1 Daniele Abbado Regista teatrale e televisivo 2 Alessandra Abbado APS Mozart 14 3 Eleonora Abbagnato Etoile Internazionale 4 Lirio Abbate Giornalista 5 Luca Abete Personaggio televisivo - Inviato Striscia La Notizia 6 Stefano Accorsi Attore 7 Vittorio Agnoletto Docente Univ Milano, Presidente LILA 8 Gian Maria Ajani già Rettore di Università di Torino 9 Antonio Albanese Attore, regista, comico, scrittore 10 Piero Alciati Ristoratore 11 Nicola Alesini Musicista 12 Sabrina Alfonsi Presidente I° Municipio Roma 13 Franco Allegrini Imprenditore Vinicolo 14 Giovanni Allevi Compositore 15 Giulia Aloisio Giornalista 16 Francesco Altan Fumettista 17 Andrea Alzetta Portavoce di Spin Time Labs roma 18 Stefano Amatucci Regista televisivo 19 Gigliola Amonini Attrice Teatrale 20 Francesco, detto Ciccio, Anastasi Slow Food Youth Network Italia 21 Roberto Andò Regista 22 Michela Andreozzi Attrice 23 Giancarlo Aneri Imprenditore Vinicolo 24 Umberto Angelini direttore artistico teatro 25 Silvia Annichiarico Attrice 26 Gianfranco Anzini Programmista rai Sindaco Torino - Città Medaglia d'oro alla 27 Chiara Appendino Resistenza 28 Bruno Aprea Direttore Orchestra 29 Alberto Asor Rosa Critico letterario, saggista 30 Patrizia Asproni Presidente Fondazione Museo Marini 31 Caterina Avanza Assist. Parlam. Europ. per Gr. Renew Europe 32 Giuseppe Ajala Magistrato 33 Gaetano Azzariti Prof. ord. Diritto Costituzionale 34 Luca Baccarelli Imprenditore Vinicolo 35 Federico Baccomo Scrittore 36 Marco Bachi (Donbachi - Bandabardò) Musicista -

Berlusconi and His Crew Published on Iitaly.Org (

Berlusconi and His Crew Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Berlusconi and His Crew E. M. (May 09, 2008) Prime Minister Berlusconi inaugurates his fourth term and announces his ministerial posts. The choices for his circle of 21 ministers reveal some predictable tactical determinations, while a few of his newbies have yet to prove their political value. No one can accuse the PM of having assembled a boring cast The 60th Italian government since the end of the Second World War was sworn in on Thursday. In a ceremony led by President Giorgio Napolitano, Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and 21 ministers of his center-right cabinet pronounced a solemn oath on the Italian Constitution. It marks the media tycoon’s fourth non-consecutive term as head of government. Berlusconi’s new cabinet rallies figures from various right-wing parties, and among them, many familiar faces. Gianni Letta, the PM’s close business and political aide, was named Cabinet Secretary, and according to Berlusconi is “a gift from God to all Italians”. Umberto Bossi [2], famously at the helm of the anti-immigration Northern League [3] party—a man stalwartly and controversially in Page 1 of 3 Berlusconi and His Crew Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) favor of a federalist system that gives greater autonomy to the North—will be minister of reforms. Roberto Calderoli [4], also of the Northern League and Berlusconi’s former minister of reforms, is now in charge of “simplification” (in other words, simplifying the Parliament and reducing its costs). Calderoli is best known in the media for having upset Muslims when he proposed pigs be brought in to discourage plans for the construction of a new mosque in Bologna and unbuttoning his shirt to reveal underneath, a t-shirt bearing an offensive cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad, setting off violent demonstrations in Libya. -

The Case of Lega Nord

TILBURG UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF TRENTO MSc Sociology An integrated and dynamic approach to the life cycle of populist radical right parties: the case of Lega Nord Supervisors: Dr Koen Abts Prof. Mario Diani Candidate: Alessandra Lo Piccolo 2017/2018 1 Abstract: This work aims at explaining populist radical right parties’ (PRRPs) electoral success and failure over their life-cycle by developing a dynamic and integrated approach to the study of their supply-side. For this purpose, the study of PRRPs is integrated building on concepts elaborated in the field of contentious politics: the political opportunity structure, the mobilizing structure and the framing processes. This work combines these perspectives in order to explain the fluctuating electoral fortune of the Italian Lega Nord at the national level (LN), here considered as a prototypical example of PRRPs. After the first participation in a national government (1994) and its peak in the general election of 1996 (10.1%), the LN electoral performances have been characterised by constant fluctuations. However, the party has managed to survive throughout different phases of the recent Italian political history. Scholars have often explained the party’s electoral success referring to its folkloristic appeal, its regionalist and populist discourses as well as the strong leadership of Umberto Bossi. However, most contributions adopt a static and one-sided analysis of the party performances, without integrating the interplay between political opportunities, organisational resources and framing strategies in a dynamic way. On the contrary, this work focuses on the interplay of exogenous and endogenous factors in accounting for the fluctuating electoral results of the party over three phases: regionalist phase (1990-1995), the move to the right (1998-2003) and the new nationalist period (2012-2018). -

Download Download

Postcolonial Borderlands: Black Life Worlds and Relational Place in Turin, Italy Heather Merrill1 Africana Studies Hamilton College, Clinton, NY, USA [email protected] Abstract The emergence of Italy as a receiving country of postcolonial immigrants from all over Africa and other parts of the economically developing world involves the reproduction of deeply rooted prejudices and colonial legacies expressed in territorial concepts of belonging. Yet geographical discussions of borders seldom begin their explorations from the vantage point of what Hanchard has called, “Black life worlds”, complex experiences of place among African diasporic populations in relationship to race. This paper examines situated practices, negotiations, and meanings of place, identity and belonging among first generation African-Italians in Northern Italy whose experiences suggest that the borders between Africa and Europe are far more porous than they appear to be. This essay develops a theory of relational place to study the meaning of place in Black life worlds as indexed by the everyday materiality of bodies in relation to racial discourses and practices, and the profound interweavings of Africa and Europe through space and time. The essay examines African-Italo experiences in relation to the transformation of political culture in Turin, the rise of ethno-nationalism, and legacies of Italian colonialism. It is not just the dominant ideas and political practices, but the marginal, the implausible, and the popular ideas that also define an age. Michael Hanchard (2006, 8) 1 Published under Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Postcolonial Borderlands 264 Introduction Maria Abbebu Viarengo spent the first twenty years of her life in Ethiopia and Sudan before her father brought her to Turin, Italy in 1969. -

La Politica Estera Dell'italia. Testi E Documenti

AVVERTENZA La dottoressa Giorgetta Troiano, Capo della Sezione Biblioteca e Documentazione dell’Unità per la Documentazione Storico-Diplomatica e gli Archivi ha selezionato il materiale, redatto il testo e preparato gli indici del presente volume con la collaborazione della dott.ssa Manuela Taliento, del dott. Fabrizio Federici e del dott. Michele Abbate. MINISTERO DEGLI AFFARI ESTERI UNITÀ PER LA DOCUMENTAZIONE STORICO-DIPLOMATICA E GLI ARCHIVI 2005 LA POLITICA ESTERA DELL’ITALIA TESTI E DOCUMENTI ROMA Roma, 2009 - Stilgrafica srl - Via Ignazio Pettinengo, 31/33 - 00159 Roma - Tel. 0643588200 INDICE - SOMMARIO III–COMPOSIZIONE DEI GOVERNI . Pag. 3 –AMMINISTRAZIONE CENTRALE DEL MINISTERO DEGLI AFFARI ESTERI . »11 –CRONOLOGIA DEI PRINCIPALI AVVENIMENTI CONCERNENTI L’ITALIA . »13 III – DISCORSI DI POLITICA ESTERA . » 207 – Comunicazioni del Ministro degli Esteri on. Fini alla Com- missione Affari Esteri del Senato sulla riforma dell’ONU (26 gennaio) . » 209 – Intervento del Ministro degli Esteri Gianfranco Fini alla Ca- mera dei Deputati sulla liberazione della giornalista Giulia- na Sgrena (8 marzo) . » 223 – Intervento del Ministro degli Esteri on. Fini al Senato per l’approvazione definitiva del Trattato costituzionale euro- peo (6 aprile) . » 232 – Intervento del Presidente del Consiglio, on. Silvio Berlusco- ni alla Camera dei Deputati (26 aprile) . » 235 – Intervento del Presidente del Consiglio on. Silvio Berlusco- ni al Senato (5 maggio) . » 240 – Messaggio del Presidente della Repubblica Ciampi ai Paesi Fondatori dell’Unione Europea (Roma, 11 maggio) . » 245 – Dichiarazione del Ministro degli Esteri Fini sulla lettera del Presidente Ciampi ai Capi di Stato dei Paesi fondatori del- l’UE (Roma, 11 maggio) . » 247 – Discorso del Ministro degli Esteri Fini in occasione del Cin- quantesimo anniversario della Conferenza di Messina (Messina, 7 giugno) . -

M Franchi Thesis for Library

The London School of Economics and Political Science Mediated tensions: Italian newspapers and the legal recognition of de facto unions Marina Franchi A thesis submitted to the Gender Institute of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, May 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 88924 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help (if applicable) I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Hilary Wright 2 Abstract The recognition of rights to couples outside the institution of marriage has been, and still is, a contentious issue in Italian Politics. Normative notions of family and kinship perpetuate the exclusion of those who do not conform to the heterosexual norm. At the same time the increased visibility of kinship arrangements that evade the heterosexual script and their claims for legal recognition, expose the fragility and the constructedness of heteronorms. During the Prodi II Government (2006-2008) the possibility of a law recognising legal status to de facto unions stirred a major controversy in which the conservative political forces and the Catholic hierarchies opposed any form of recognition, with particular acrimony shown toward same sex couples. -

Y:\Cantieri\Rassegna Stampa\Rassegna Bcc\2011\6-12

PRESSToday Rassegna stampa 06/09/2011 : Notizie del mese Arena, L' Previdenza, Bossi resiste alle pressioni Avvenire Pensioni, ultimo assalto del premier a Bossi senza titolo........... Bresciaoggi(Abbonati) Il Quirinale gela la manovra: Servono misure più efficaci Previdenza, Bossi resiste alle pressioni Centro, Il allarme delle parti sociali su tasse e pensioni slitta la consulta del patto - fabio casmirro Gazzetta del Sud Doppio duello del premier con Tremonti (Iva) e Bossi (pensioni) Italia Oggi Intanto servizio militare e laurea si sono salvati Pensione più lontana per 17 mila Riscatti, c'era l'ok dell'Economia Troppi benefici finali per versamenti iniziali quasi simbolici Solidarietà dai baby pensionati Manifesto, Il Tre anni di tagli sono già troppi Milano Finanza (MF) Manovra, il Cav apre l'ombrello Iva Quel pasticciaccio sull'eliminazione del riscatto della laurea Repubblica, La il cavaliere e l'incubo della trappola "ora pensioni e iva o salta tutto" - (segue dalla prima pagina) francesco bei Sole 24 Ore, Il E adesso rispuntano contributo solidarietà e aumento dell'Iva Senza titolo Subito il collegamento con i costi standard 07/09/2011 : Notizie del mese Arena, L' Berlusconi blinda la manovra Sale l'Iva e colpo alle pensioni Iva, pensioni, supertassa: ecco la manovra blindata Siamo contrari sia all'aumento dell'età pensionabile per le donne, sia all'aumento dell'I... Cittadino, Il Nuova previdenza "rosa" a regime nel 2014 A regime l'intervento varrà 4 miliardi di euro Corriere della Sera Donne, Anticipato al 2014 l'Aumento (Graduale)