The Wheels Keep on Turning: Is the End of Rail Franchising in Britain in Sight?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia

Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Contents Foreword 3 Looking Ahead 5 Priorities in Detail • Great Eastern Main Line 6 • West Anglia Main Line 6 • Great Northern Route 7 • Essex Thameside 8 • Branch Lines 8 • Freight 9 A five county alliance • Norfolk 10 • Suffolk 11 • Essex 11 • Cambridgeshire 12 • Hertfordshire 13 • Connecting East Anglia 14 Our counties connected 15 Foreword Our vision is to release the industry, entrepreneurship and talent investment in rail connectivity and the introduction of the Essex of our region through a modern, customer-focused and efficient Thameside service has transformed ‘the misery line’ into the most railway system. reliable in the country, where passenger numbers have increased by 26% between 2005 and 2011. With focussed infrastructure We have the skills and enterprise to be an Eastern Economic and rolling stock investment to develop a high-quality service, Powerhouse. Our growing economy is built on the successes of East Anglia can deliver so much more. innovative and dynamic businesses, education institutions that are world-leading and internationally connected airports and We want to create a rail network that sets the standard for container ports. what others can achieve elsewhere. We want to attract new businesses, draw in millions of visitors and make the case for The railways are integral to our region’s economy - carrying more investment. To do this we need a modern, customer- almost 160 million passengers during 2012-2013, an increase focused and efficient railway system. This prospectus sets out of 4% on the previous year. -

Firstgroup Vies with Virgin in West Coast Rail Bidding War | Business | Guardian.Co.Uk Page 1 of 2

FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war | Business | guardian.co.uk Page 1 of 2 Printing sponsored by: FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war Aberdeen-based group is frontrunner, along with incumbent, in battle to secure 14-year franchise contract Dan Milmo, industrial editor guardian.co.uk, Sunday 15 July 2012 14.13 BST Virgin, the current holders of the west coast franchise, pay an annual premium of £150m to the government. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian FirstGroup has emerged as a frontrunner for the multibillion-pound west coast rail franchise alongside incumbent Virgin Trains, with the contest now a two-horse race between the experienced operators. Aberdeen-based FirstGroup is vying with Virgin despite announcing last year that it is handing back its Great Western rail contract three years ahead of schedule, avoiding more than £800m in payments to the government. The Department for Transport is expected to bank a considerable windfall from the new 14-year west coast contract, with Virgin currently paying an annual premium of about £150m to the state. Both bidders are expected to promise an even bigger number over the life of the new franchise. The winner is expected to be announced next month. It is understood that FirstGroup and Virgin are still in talks with the DfT, but two foreign-owned bidders on the four-strong shortlist are no longer considered likely contenders. They are a joint venture between public transport operator Keolis and SNCF, the French state rail group, and a bid from Abellio, which is controlled by the Dutch national rail operator. -

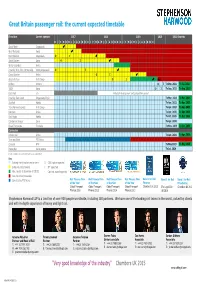

Great Britain Passenger Rail: the Current Expected Timetable

Great Britain passenger rail: the current expected timetable Franchise Current operator 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Onwards DJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASOND South West Stagecoach West Midlands Govia East Midlands Stagecoach O I South Eastern Govia O I Wales & Borders Arriva InterCity W.C./W.C. Partnership Virgin/Stagecoach O I Cross Country Arriva OI Great Western First Group OI Apr. Chiltern Chiltern OITo Dec. 2021 To Jul. 2022 TSGN Govia O I To Sep. 2021 To Sep. 2023 East West n/a Potential development and competition period InterCity East Coast Stagecoach/Virgin To Mar. 2023 To Mar. 2024 ScotRail Abellio To Apr. 2022 To Apr. 2025 TransPennine Express First Group To Apr. 2023 To Apr. 2025 Northern Arriva To Apr. 2025 To Apr. 2026 East Anglia Abellio To Oct. 2025 To Oct. 2026 Caledonian Sleeper Serco To Apr. 2030 Essex Thameside Trenitalia To Nov. 2029 To Jun. 2030 Concession London Rail Arriva To Apr. 2024 To Apr. 2026 Tyne and Wear PTE Nexus Crossrail MTR To May 2023 To May 2025 MerseyRail Serco/Abellio To Jul. 2028 Based on publicly available information as at 1 April 2017 Key Existing franchise/concession term O OJEU notice expected Extension/direct award I ITT expected Max. length at discretion of DfT/TS Contract award expected New franchise/concession Operated by PTE Nexus Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail of the Year of the Year of the Year of the Year Finance Franchising Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Chambers UK 2015 The Legal 500 Chambers UK 2017 Finance 2016 Finance 2015 Finance 2014 Finance 2013 UK 2016 Stephenson Harwood LLP is a law firm of over 900 people worldwide, including 150 partners. -

United Kingdom-London: Railway Transport Prior Information Notice for a Public Service Contract

United Kingdom-London: Railway transport Prior information notice for a public service contract Form for notification under Article 7(2) of Regulation 1370/2007, as amended by the Regulation (EC) No 1370/2007 (Public Service Obligations in Transport) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020, to be published one year before the launch of the invitation to tender procedure or direct award on the Department’s website. Competent authorities may decide not to publish this information where a public service contract concerns an annual provision of less than 50 000 kilometres of public passenger transport services. Section I: Competent authority I.1 Name and addresses Department for Transport Great Minster House, 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR United Kingdom Contact person: E-mail: [email protected] NUTS code: UKI32 Westminster Internet address(es): Main address: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-transport 2 I.2 Contract award on behalf of other competent authorities I.3 Communication Additional information can be obtained from the above-mentioned address I.4 Type of competent authority Ministry or any other national or federal authority, including their regional or local subdivisions Section II: Object II.1 Scope of the procurement II.1.1 Title Contract for West Coast Partnership Rail Services. Currently operated by First Trenitalia West Coast Rail Limited II.1.2 Main CPV code 60200000 Railway transport services II.1.3 Type of contract Services Areas covered by the public transport services: Rail transport services II.2 Description II.2.2 Additional CPV code(s) 60210000 Public transport services by railways II.2.3 Place of performance NUTS code: UKI LONDON NUTS code: UKD NORTH WEST (ENGLAND) NUTS code: UKG WEST MIDLANDS (ENGLAND) NUTS code: UKM SCOTLAND 3 NUTS code: UKL WALES NUTS code: UK UNITED KINGDOM NUTS code: UKJ SOUTH EAST (ENGLAND) Main site or place of performance: West Coast Partnership rail services link London Euston, the West Midlands, North West England, North Wales and Scotland. -

Draft Portfolio Holder Decision Notice

PHD674 Ward(s): General DRAFT PORTFOLIO HOLDER DECISION NOTICE PROPOSED INDIVIDUAL DECISION BY THE PORTFOLIO HOLDER FOR HIGH QUALITY ENVIRONMENT) TOPIC – STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION SOUTH WESTERN RAIL FRANCHISE PROCEDURAL INFORMATION The Access to Information Procedure Rules – Part 4, Section 22 of the Council’s Constitution provides for a decision to be made by an individual member of Cabinet. In accordance with the Procedure Rules, the Chief Operating Officer, the Chief Executive and the Chief Finance Officer are consulted together with Chairman and Vice Chairman of The Overview and Scrutiny Committee and any other relevant overview and scrutiny committee. In addition, all Members are notified. Five or more of these consulted Members can require that the matter be referred to Cabinet for determination. If you wish to make representation on this proposed Decision please contact the relevant Portfolio Holder and the following Democratic Services Officer by 5.00pm on Wednesday 10 February 2016. Contact Officers: Case Officer: Dan Massey, Tel: 01962 848534, Email: [email protected] Democratic Services Officer: Nancy Graham, Tel: 01962 848235, Email: [email protected] SUMMARY The South Western rail franchise is a vital part of the national rail network that serves a market extending from central and south west London to major towns and cities in Berkshire, Devon, Dorset, Hampshire, Surrey and Wiltshire; it also provides services on the Isle of Wight. The franchise area serves a diverse market providing connectivity that includes airports, ports, universities, sporting and cultural centres, theme parks and National Parks. The South Western rail franchise supports commuters, businesses, and local communities, as well as providing services for the tourist and leisure markets. -

Investor Report 01 01 16

Investor Report 1 July 2018 – 30 June 2019 1 Angel Trains Investor Report – 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012 1 GENERAL OVERVIEW Angel Trains Group (the “Group”) performed strongly during the period with EBITDA at £412.1m, an increase of £1.3m on the corresponding previous 12 month period. The Group has maintained credit metrics consistent with the Baa2 credit rating throughout the period, following the rating affirmation by Moody’s during December 2018. At 30 June 2019 the Group owned 4,421 vehicles. During the period, new leases were entered into with nine franchises (including four franchise extensions), accounting for 1,802 vehicles (40.8%) of the Group’s existing portfolio. Between 2019 and 2022 a further 1,376 vehicles are due for re- lease; excluding those which are covered by Section 54 undertakings. During the same period an additional 120 new bi-mode vehicles will be delivered. At the period end, 96.6% of the Group’s portfolio was on lease. The off-lease vehicles are a small number of Class 317 and HST vehicles. All are life expired with no further economic value attributed to them. A small number of Class 442 vehicles are earmarked for disposal. 2 SIGNIFICANT BUSINESS DEVELOPMENTS 2.1 New significant business developments for the period ending 30 June 2019 New Trains There were no new train procurements during the period. However, focus on project management delivery continues with regards the following new trains: Angel Trains is procuring 24 x 5-car AT300 bi-mode intercity trains (Class 802), which will be manufactured by Hitachi Rail Europe and utilised by FirstGroup on the TransPennine Express (“TPE”) franchise and by First Hull Trains. -

Railway Development Society Limited Is a Not-For-Profit Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England & Wales No.5011634

railse no. 132 June 2016 Railfuture in London and the South East quarterly branch newsletter The independent campaign for a bigger better passenger and freight rail network Railfuture campaign wins reopened National Infrastructure Commission east London station at Lea Bridge wants Crossrail 2 hybrid bill in 2019 Between Stratford and Tottenham Hale, opened on Lord Adonis and his team of seven Commissioners 15 September 1840, closed 8 July 1985 with the end of may only have been appointed since last October, and Stratford-Tottenham Hale shuttle services, reopened the CEO since December, but their output and current 31 years later on 15 May 2016 (officially on 16 May). casework is already substantial. For London and the South East there has been last November’s Call for Evidence on London’s Transport Infrastructure, to which Railfuture responded in January, and which in March resulted in two reports: ‘Transport for a World City’ and, from an independent panel of experts, the supporting ‘Review of the case for large scale transport investment in London’ both of which include a specific focus on Crossrail 2. The NIC calls for a hybrid bill deposit in autumn 2019 for line opening in 2033, to coincide with HS2 opening to Leeds and Manchester and the need for the double- ended Euston St. Pancras station to add distribution capacity. It also advocates deferral of the £4billion New Southgate branch, noting that it would enable the proposed eastern extension to be considered when the Lea Bridge station – looking south, towards Stratford second phase of the scheme is planned. It “would be more expensive, but could bring greater overall This is the culmination of a campaign which local benefits, particularly in relation to its impacts in Railfuture members, individual and affiliated, can justly unlocking housing and economic growth in the east of claim as their own. -

Drivers'union

The train ASLEF drivers’ union >>> Rail Franchise Handbook 2019 ASLEF Introduction Welcome to our new Rail Franchise Handbook. I hope you will find it as interesting, and useful, as I do and a valuable tool for the political and industrial work you do for our union. We put this handbook together to give our reps and decision makers the inside track on who really runs Britain’s railways, how they run our railways, and what they take out from our railway industry every year. Because we believe the facts and figures revealed in these pages show, with crystal clarity, the utter folly of our privatised, and fragmented, franchise system. A structure – set up by John Major, 25 years ago, and continued by Conservative governments ever since – that separates the wheels and steel and is underwritten by an enormous public subsidy from every taxpayer in this country, and sky high passenger fares, while tens of millions of pounds haemorrhage from the system into the pockets of shareholders in the form of profits and dividends, or increasingly due inefficiencies. In fact whilst the system has never worked for passengers or taxpayers, there are now signs that it doesn’t work for operators either. The franchising system has been put on hold for a couple of years now due to a lack of bidders. This means direct awards have been handed out leading to even less competition. So we now have a system that exists to maintain the system itself, not our railway. It isn’t true to say that all the train and freight operating fill the pockets of shareholders; some TOCs and FOCs are owned by public, not private, operators where shareholders do not skim the cream off the top of the milk. -

Rail Business Report PDF 3 MB

Transport Delivery Committee Date 06 January 2020 Report title Rail Business Report Accountable Director Malcolm Holmes, Director of Rail, Transport for West Midlands Email [email protected] Tel 0121 214 7058 Accountable Tom Painter, Head of Rail Franchising and Employee Partnerships, West Midlands Rail Executive Email [email protected] Tel: 07432104161 Report has been Councillor Roger Lawrence – Lead Member Rail and considered by Metro Recommendation(s) for action or decision: The Transport Delivery Committee is recommended to: Note the content of the report 1.0 Purpose To provide an update relating to the performance, operation and delivery of rail services in the West Midlands including on rail operator partnership agreements and West Midlands Rail Executive (WMRE) activity. 2.0 Section A – Background 2.1 Transport for West Midlands (TfWM) and WMRE currently work to influence the management and delivery of rail services and projects. Page 1 of 9 [PUBLIC] 2.2 This report provides a summary of rail activity in the TfWM and wider WMRE areas between September and December 2019. 3.0 Section B – Williams Rail Review, West Coast Franchise and HS2 Williams Rail Review 3.1 Publication of the William’s Review has now been delayed until after the election. West Coast Franchise 3.2 The new (FirstGroup / FS Trenitalia) Avanti West Coast company replaced Virgin Trains as the operator of the West Coast franchise from Sunday 8th December. 3.3 The West Coast Partnership franchise connects important West Midlands centres such as Rugby, Coventry, Birmingham Airport/NEC, Birmingham, Sandwell & Dudley, Wolverhampton and Stafford with London, the North West and Scotland. -

First MTR / South Western

Anticipated acquisition by First MTR South Western Trains Limited of the South Western Franchise Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6664/16 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 11 July 2017. Full text of the decision published on 24 July 2017. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. SUMMARY 1. On 27 March 2017, the Department for Transport (DfT) announced that First MTR South Western Trains Limited (FMSWTL), a joint venture between FirstGroup plc (First) and MTR Corporation (MTR and together with First, the Parties), was the successful bidder for the South Western Franchise. DfT and FMSWTL entered a franchise agreement and associated agreements confirming the award of the South Western Franchise to FMSWTL (the Franchise Award). The South Western Franchise is due to commence on 20 August 2017 for an initial term of seven years, expiring on 18 August 2024 (subject to a possible extension of 11 reporting periods1). 2. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) believes that it is or may be the case that the Parties’ enterprises have ceased to be distinct. The UK turnover of the South Western Franchise exceeds £70 million, so the turnover test in section 23(1)(b) of the Act is satisfied. The CMA therefore believes that it is or may be the case that a relevant merger situation has been created. 3. The Franchise Award also meets the thresholds under Council Regulation (EC) 139/2004 (the EU Merger Regulation) for review by the EU 1 44 weeks. -

CMA Discussion Document: Competition in Passenger Rail Services in Great Britain – Firstgroup Plc Response

CMA discussion document: competition in passenger rail services in Great Britain – FirstGroup plc response Contents Background ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Rail privatisation has delivered significant benefits ............................................................................... 2 Ongoing upheaval in the rail industry ..................................................................................................... 3 The industry is competitive ..................................................................................................................... 3 Capacity constraints ................................................................................................................................ 6 Open access ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................. 9 1 Background 1. FirstGroup plc (“First”) is a public limited company operating public transport services in the UK, Ireland and North America. It is listed on the London Stock Exchange and operates five business divisions: (a) First Student: this business division provides student transportation services in North America; (b) First Transit: this business division provides public transit management -

Dft West Coast Partnership -- Transform Scotland Briefing For

DfT ‘West Coast Partnership’ Transform Scotland Briefing for Bidders 13 November 2017 1. About Transform Scotland 1.1. Transform Scotland is the national alliance for sustainable transport, bringing together organisations from the private, public and voluntary sectors. We campaign for a society where everyone can have their travel needs met within the limits of a transport system that is environmentally sustainable, socially inclusive and economically responsible. 2. Introduction and General Comments 2.1. Transform Scotland welcomes the opportunity to comment on this important new Partnership for the West Coast Main Line (WCML) and the subsequent introduction of HS2 services. Our comments are confined to journeys between Scotland and England and within Scotland. 2.2. We initially ofered comments on the West Coast refranchising in April 2011. Referring back to those earlier comments, much of what we asked for at the time remains to be delivered. However, it is pleasing to note that some aspects have already been delivered by the current franchise holder, Virgin Trains. In particular electric traction with tilt has been introduced on the Edinburgh and Glasgow to Birmingham routes. These trains have been extended to London, thereby directly serving many more destinations from Scotland, which has resulted in significant passenger growth on these routes. We also sought direct trains from Scotland to Liverpool; these are to be delivered, albeit by the TransPennine Express (TPE) franchise. 2.3. Looking ahead, it remains the case that this key rail route ofers tremendous potential for modal shift to rail from both plane and car. It is a telling fact that people in the UK fly more per head of population than anywhere else in the world – including the US.