John Guare's Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

ACTRESS: LUCIA MÉTRAILLER/Imdb

ACTRESS: LUCIA MÉTRAILLER/IMDb NOTE: Text highlighted in yellow are clickable links HEADSHOTS / WEBSITE: http://www.actlucia.com WEB PAGE: https://www.actlucia.com/pages/pgfcvdtsrr.html CELL PHONE: (412) 726-2208 EMAIL: [email protected] (Website contains over 30 film/22 voiceover demo reels & headshots) FILMS/TV & WEB SERIES LITTLE MOUSE - (Horror/Feature Film) - April Larimer/Grandmother/Support Role/Director: Delaney Hathaway/Before I Wake Productions APPARITIONAL - (Psychological Thriller) - Suzanne/Psychic/Lead Role/Director: Lauren Keller/Point Park University Intermediate Directing Class NIAGRA FALLS - (Comedy/Web Series) - Eunice/Elderly Lady/Support Role/Director: Dayne Jefferson PAXI - (Psychological Thriller) - Dr. Rose Williams/Psychiatric Doctor/Lead Role/Director: Benjamyn/Point Park University THE ROUTES OF WILD FLOWERS - (IMDb/Adventure/Feature) - Janet/Divorced Mother/Lead Role/ Director: Jon M. Brence/Veriyoung Productions MISSED CUES - (IMDb/Comedy/Feature) - Ellen Taylor/News Anchor/Support Role/Director: Lisa Seelinger/ Seelinger Productions REFERENCE POINT- (IMDb/TV Series) - SEASON 2/EPISODE 2 - ONE YEAR EARLIER - Copier Killer/Copier Protector/ John Cantine REFERENCE POINT - (IMDb/TV Series) - SEASON 1/EPISODE 2 - LIKE A HAWK - Copier Killer/Copier Protector/ John Cantine REFERENCE POINT - (IMDb/TV Series) - SEASON 1/EPISODE 1 - NEW LIBRARIAN - Copier Killer/Copier Protector/ John Cantine WRONG NUMBER - (IMDb/Drama/Crime) - Rosemary/Mother/Support Role/Director: Eric Rogers/Screenwriter for NYPD Blue FIVE MINUTE MAKEOVER - (Comedy Series) - Lucia Smithe/British Nutritionist/Support Role/Director: Sola Oyinkansola Carnegie Mellon University SPACE AND TIME - (Sci Fi/Drama) - Older Sally/Sister dying in hospital/Support Role/Director: Ryan Sobota/Point Park University DOLORES CLAIBORNE - (Crime/Drama/Mystery) - Dolores Claiborne/Maid/Lead Role/Director: Jacob E. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Current Season Poster

2019-2020 PERFORMANCE SEASON MainstageMainstage SeriesSeries TheThe HouseHouse ofof BlueBlue LeavesLeaves by John Guare It’s 1965, the day Pope Paul VI came to New York City. For Artie Shaughnessy of Sun- nyside, Queens, this historic moment is an omen for change. Artie dreams of leaving his zookeeper job to pursue a life as a songwriter in Hollywood with his new girlfriend, Bunny. However, a few things stand in his way, such as his wife, Bananas; a GI son drafted into Vietnam gone AWOL; a grieving movie producer; and a group of over-ex- cited nuns. When these worlds collide, hilarity ensues. This dark comedy explores the theme of the American Dream at a moment in U.S. history ripe with change. November 1- 2 @7PM and November 2-3 @2PM . $10 General Admission, $8 Seniors, Faculty, & Staff, $5 Students CelebratingCelebrating thethe Green:Green: ChristmasChristmas BellesBelles Jewell Theatre Company and Jazz Band collaborate to present a classic holiday story combining reader’s theatre with live music. The performance is part of Jewell’s annual winter holiday events for the entire campus and community. Free performance. November 22, Following the Lighting of the Quad Free Admission or Donation November 23 @ 2PMZ A Pay What You Wish Event AA Gentleman’sGentleman’s GuideGuide toto LoveLove andand MurderMurder book and lyrics by Robert L. Freedman & the music and lyrics by Steven Lutvak When the humble Monty Navarro learns that he is eighth in line for an earldom in the D’Ysquith family fortune, he plans to knock off his unsuspecting relatives to become the ninth Earl of Highhurst. -

New Books FALL + WINTER 2020 PAGE Contents 11 African American Studies

New Books FALL + WINTER 2020 PAGE contents 11 African American Studies ..... 2, 13 Civil Rights ...............1, 4, 9 Folklore ......................11 Literary Studies ..............15–18 Memoir ......................4 Music ........................5 Rhetoric ..................19–20 South Carolina ...1–3, 5–7, 9–10, 12 Southern History ...........8, 10 PAGE World History ..............13–14 4 FALL + WINTER 2020 New in Ebook .............. 21–24 HIGHLIGHTS Cover Image: Leaders of the 1969 Mother’s Day March, a hospital workers' strike, in Charleston (by Cecil J. Williams.), from Stories of Struggle. Above: S. H. Kress and Co. in Orangeburg removed the seats of its counter stools to thwart student sit-ins (by Cecil J. Williams), from Stories of Struggle. SOUTH CAROLINA / CIVIL RIGHTS In this pioneering study of the long and arduous struggle for civil rights in South Carolina, journalist Claudia Smith Brinson details the lynchings, beatings, cross burn- ings, and venomous hatred that black South Carolinians endured—as well as the astonishing courage, dignity, and com- passion of those who risked their lives for equality. Through extensive research and interviews with more than 150 civil rights activists, Brinson chronicles twenty pivotal years of petitioning, picketing, boycotting, marching, and holding sit-ins. These intimate stories of courage, both heartbreaking and inspiring, shine a light on the progress achieved by nonviolent civil rights activists while also revealing white South Carolinians’ often violent resistance to change. Although significant racial dis- parities remain, the sacrifices of these brave Stories of men and women produced real progress— and hope for the future. Struggle CLAUDIA SMITH BRINSON, a South Car- The Clash over Civil Rights in olina journalist for more than thirty years, South Carolina has won more than thirty awards, including Knight Ridder’s Award of Excellence and an CLAUDIA SMITH BRINSON O. -

Feminist Theory and Postwar American Drama

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 Feminist Theory and Postwar American Drama Gayle Austin The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2149 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

Oregon Shakespeare Festival Production History = 1990S 1991

Oregon Shakespeare Festival Production History = 1990s 1991 saw the retirement of Jerry Turner, and the appointment of Henry Woronicz as the third Artistic Director in the Festivals 56 year history. The year also saw our first signed production, The Merchant of Venice. The Allen Pavilion of the Elizabethan Theatre was completed in 1992, providing improved acoustics, sight-lines and technical capabilities. The Festival’s operation in Portland became an independent theatre company — Portland Center Stage — on July 1, 1994. In 1995 Henry Woronicz announces his resignation and Libby Appel is named the new Artistic Director of the Festival. The Festival completes the canon for the third time in 1997, again with “Timon of Athens.” The Festival’s production of Lillian Garrett-Groag’s The Magic Fire plays at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC from November 10 through December 6, 1998, and is selected by Time Magazine as one of the year’s Ten Best Plays. In this decade the Festival produced these World Premieres, including adaptations: 1990 - Peer Gynt,1993 - Cymbeline, 1995 - Emma’s Child, 1996 - Moliere Plays Paris, 1996 – The Darker Face of the Earth, 1997 - The Magic Fire, 1998 - Measure for Measure, 1999 - Rosmersholm,1999 - The Good Person of Szechuan Year Production Director Playwright Theatre 1990 Aristocrats Killian, Philip Friel, Brian Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 At Long Last Leo Boyd, Kirk Stein, Mark Black Swan 1990 The Comedy of Errors Ramirez, Tom Shakespeare, William Elizabethan Theatre 1990 God's Country Kevin, Michael Dietz, Steven Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 Henry V Edmondson, James Shakespeare, William Elizabethan Theatre 1990 The House of Blue Leaves McCallum, Sandy Guare, John Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 The Merry Wives of Windsor Patton, Pat Shakespeare, William Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 Peer Gynt Turner, Jerry Ibsen, Henrik Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 The Second Man Woronicz, Henry Behrman, S.N. -

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected]

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected] CASTING DIRECTOR (selected) Holler If Ya Hear Me (Todd Kreidler) Palace Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon (upcoming) Casa Valentina (Harvey Fierstein) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello (upcoming) Commons of Pensacola (Amanda Peet) Manhattan Theater Club dir. Lynne Meadow The Snow Geese (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan All New People (Zach Braff) Second Stage Theatre dir. Peter DuBois Water By The Spoonful (Quiara Hudes) Second Stage Theatre dir. Davis McCallum My Name Is Rachel Corrie Minetta Lane/Off-Broadway dir. Alan Rickman Complicit (Joe Sutton) Old Vic/London dir. Kevin Spacey Orphans (Lyle Kessler) Schoenfeld Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan Lonely I’m Not (Paul Weitz) Second Stage Theatre dir. Trip Cullman Tales of the City: the musical American Conservatory Theatre dir: Jason Moore Romantic Poetry (John P. Shanley) MTC/Off-Broadway dir: John P. Shanley Trip to Bountiful (Horton Foote) Sondheim Theatre/ Broadway dir. Michael Wilson Dead Accounts (Theresa Rebeck) Music Box Theatre/ Broadway dir. Jack O’Brien Fences (August Wilson) Cort Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon Sweet Bird of Youth (T. Williams) Goodman Theatre/ Chicago dir. David Cromer The Other Place (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello Seminar (Theresa Rebeck) Golden Theatre/ Broadway dir. Sam Gold Grace (Craig Wright) Court Theatre/ Broadway dir. Dexter Bullard Bengal Tiger … (Rajiv Josef) Richard Rodgers/ Broadway dir. Moises Kaufman Stick Fly (Lydia Diamond) Cort Theatre/ Broadway dir. Kenny Leon The Columnist (David Auburn) Freidman Theatre/Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan The Royal Family (Ferber) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. -

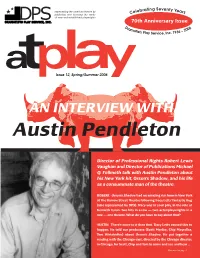

At Play Spring-Summer 06.Indd

rating Seventy Y representing the american theatre by eleb ears publishing and licensing the works C of new and established playwrights 70th Anniversary Issue D ram 06 ati – 20 sts Play Service, Inc. 1936 Issue 12, Spring/Summer 2006 AN INTERVIEW WITH Austin Pendleton Director of Professional Rights Robert Lewis Vaughan and Director of Publications Michael Q. Fellmeth talk with Austin Pendleton about his New York hit, Orson’s Shadow, and his life as a consummate man of the theatre. ROBERT. Orson’s Shadow had an amazing run here in New York at The Barrow Street Theatre following Tracy Letts’ fantastic Bug (also represented by DPS). Tracy was in your play, in the role of Kenneth Tynan. Two hits in a row — two actor/playwrights in a row — one theatre. What do you have to say about that? AUSTIN. There’s more to it than that. Tracy Letts caused this to happen. He told our producers (Scott Morfee, Chip Meyrelles, Tom Wirtshafter) about Orson’s Shadow. He put together a reading with the Chicago cast, directed by the Chicago director, in Chicago, for Scott, Chip and Tom to come and see and hear … Continued on page 3 NEWPLAYS Serving the American Theatre Since 1936: A Brief History of Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Rob Ackerman DISCONNECT. Goaded by the women they love “The Dramatists Play Service came into being at exactly the right moment and haunted by memories they can no longer for the contemporary playwright and the American theatre at large.” suppress, two men at a dinner party confront the —Audrey Wood, renowned agent to Tennessee Williams lies of their lives. -

UE Theatre Viewbook

Department of Theatre 1800 Lincoln Avenue Evansville, Indiana 47722 theatre.evansville.edu [email protected] University of Evansville Theatre 812.488.2744 Educating future professionals. PERFORMANCE Bachelor of Fine Arts Bachelor of Science PEER GYNT, May Studio Theatre EXPERIENCE Performance majors experience in-depth UE THEATRE... classroom training in improvisation, games, clowning, voice and speech, movement, UE Theatre encourages students to explore the script analysis, character and scene study full breadth of career development opportunities (utilizing contemporary and classical texts), available to them throughout the entertainment as well as advanced audition techniques. industry. The mentoring of each student’s This comprehensive curriculum prepares HAMLET, Shanklin Theatre particular strengths and talents is coupled with them to work on a wide range of material practical experiences in auditions, mock job in multiple mediums. interviews, portfolio development, and a true desire to foster personal and professional success for Mainstage and studio productions, student- every graduate. directed projects, classroom work, and UE Theatre productions provide purposeful experiences tailored to challenge and cultivate growth in an staged readings, as well as a traveling individual student’s path as a theatre artist. Students have the opportunity to work in all three venues: Shakespeare troupe, allow actors to the 482-seat Shanklin Theatre, the versatile May Studio Theatre, and the newly created John David Lutz further develop and perfect their craft in a Theatre Lab. variety of hands-on settings. THE WOLVES, May Studio Theatre Theatre Studies majors must be of the highest THEATRE STUDIES academic caliber, possess demonstrated talent, THEATRE MANAGEMENT and exhibit an interest and proficiency in Bachelor of Science several areas of theatre. -

Cast Setting

Directed by Belinda (Be) Boyd CAST (in alphabetical order) Evan...........................................................................................BRYANT BENTLEY* Jason...........................................................................................AUSTIN CARROLL Chris........................................................................................DYLAN T. JACKSON* Cynthia.................................................................................TRACEY CONYER LEE* Stan...........................................................................JOHN LEONARD THOMPSON* Tracey.........................................................................................KIM COZORT KAY* Jessie...........................................................................................JENNIFER JONES Oscar........................................................................................GABRIELL SALGADO Brucie........................................................................................BRANDON MORRIS Stage Directions...........................................................................IAIN BATCHELOR* SETTING Reading, Pennsylvania 2000/2008 *Member of Actors’ Equity Association the union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States BRYANT BENTLEY (Evan) is a native TRACEY CONYER LEE (Cynthia) of Dayton, Ohio and now resides in appeared as Billie Holiday in PBD’s Columbus. He’s been a professional production of Lady Day at Emerson’s actor for 20 years, and is excited Bar & Grill. Recent -

PUMP BOYS and DINETTES

PUMP BOYS and DINETTES to star Jordan Dean, Hunter Foster, Mamie Parris, Randy Redd, Katie Thompson, Lorenzo Wolff Directed by Lear deBessonet; Choreographed by Danny Mefford Free Pre-Show Events Include Original Casts of “Pump Boys” and [title of show] July 16 – July 19 2014 Encores! Off- Center Jeanine Tesori, Artistic Director; Chris Fenwick, Music Director New York, N.Y., May 27, 2014 - Pump Boys and Dinettes, the final production of the 2014 Encores! Off-Center series, will star Jordan Dean, Hunter Foster, Mamie Parris, Randy Redd, Katie Thompson and Lorenzo Wolff. Pump Boys, running July 16 – 19, will be directed by Lear deBessonet and choreographed by Danny Mefford. Jeanine Tesori is the Encores! Off-Center artistic director; Chris Fenwick is the music director. Pump Boys and Dinettes was conceived, written and performed by John Foley, Mark Hardwick, Debra Monk, Cass Morgan, John Schimmel and Jim Wann. The show is a musical tribute to life on the roadside, with the actors accompanying themselves on guitar, piano, bass, fiddle, accordion, and kitchen utensils. A hybrid of country, rock and pop music, Pump Boys is the story of four gas station attendants and two waitresses at a small-town dinette in North Carolina. It premiered Off-Broadway at the Chelsea West Side Arts Theatre in July 1981 and opened on Broadway on February 4, 1982 at the Princess Theatre, where it played 573 performances and was nominated for both Tony and Drama Desk Awards for Best Musical. THE ARTISTS Jordan Dean (Jackson) appeared on Broadway in Mamma Mia!, Cymbeline and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.