H-Diplo Roundtable, Vol. XIV, No. 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argreportopt.Pdf

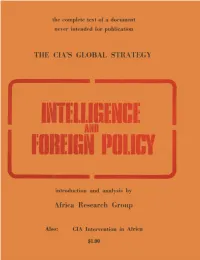

A NECESSARY INTRODUCTIQN PREFACE There are few people wi h any degree of. political literacy anywhere in the world. who have nQt heard about the CIA. Its n oriety is well deserved even if its precise functions in the service of the American Empire often isappear under a cloud of fictional images or crude conspiratorial theories. The Africa Research Gr up is now able to make available the text of a document which helps fill many of the existing ga in understanding the expanded role intelligence agellci~s play in plannin and executing f reign policy objectives. "Intelligence and Foreign Policy," as the document is titled, illumi tes the role of covert action. It enumerates the mechanisms which allow the United States t interfere, with almost routine regularity, in the internal affairs of sovereign nations through ut the world.- We are p~blishing it for many of th~ ,same reason that .American newspapers de ·ed governmel)t censorship to disclose the secret,o igins ,0 the War against the people of Indo hina. Unlike those newspapers, however, we feel the pu~lic ~as more than a "right to know"; it has the duty to struggle against the system which needs and uses the CIA. In addition to the docum nt, the second section of the pamphlet examines CIA inv~lve~ent in a specific setting: its role in the pacification of the Leftist opposition in Kenya, and its promotion of "cultural nationalism" i lother reas of Africa. The larger strategies spoken of in the document here reappear as the dail interventions of U.S. -

WISCONSIN MAGAZINE of HISTORY the State Historical Society Ofwisconsin • Vol

(ISSN 0043-6534) WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY The State Historical Society ofWisconsin • Vol. 75, No. 3 • Spring, 1992 fr»:g- •>. * i I'^^^^BRR' ^ 1 THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN H. NICHOLAS MULLER III, Director Officers FANNIE E. HICKLIN, President GERALD D. VISTE, Treasurer GLENN R. COATES, First Vice-President H. NICHOLAS MULLER III, Secretary JANE BERNHARDT, Second Vice-President THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN is both a state agency and a private membership organization. Founded in 1846—two years before statehood—and chartered in 1853, it is the oldest American historical society to receive continuous public funding. By statute, it is charged with collecting, advancing, and dissemi nating knowledge ofWisconsin and ofthe trans-Allegheny West The Society serves as the archive ofthe State ofWisconsin; it collects all manner of books, periodicals, maps, manuscripts, relics, newspapers, and aural and graphic materials as they relate to North America; it maintains a museum, library, and research facility in Madison as well as a statewide system of historic sites, school services, area research centers, and affiliated local societies; it administers a broad program of historic preservation; and publishes a wide variety of historical materials, both scholarly and popular. MEMBERSHIP in the Society is open to the public. Individual memhersh'ip (one per son) is $25. Senior Citizen Individual membership is $20. Family membership is $30. Senicrr Citizen Family membership is $25. Suppcrrting memhershvp is $100. Sustaining membership is $250. A Patron contributes $500 or more. Life membership (one person) is $1,000. MEMBERSHIP in the Friends of the SHSW is open to the public. -

John F. Kennedy, Ghana and the Volta River Project : a Study in American Foreign Policy Towards Neutralist Africa

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-1989 John F. Kennedy, Ghana and the Volta River project : a study in American foreign policy towards neutralist Africa. Kurt X. Metzmeier 1959- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Metzmeier, Kurt X. 1959-, "John F. Kennedy, Ghana and the Volta River project : a study in American foreign policy towards neutralist Africa." (1989). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 967. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/967 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN F. KENNEDY, GHANA AND THE \\ VOLTA RIVER PROJECT A Study in American Foreign Policy towards Neutralist Africa By Kurt X. Metzmeier B.A., Universdty of Louisville, 1982 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 1989 JOHN F. KENNEDY, GHANA AND THE VOLTA RIVER PROJECT A Study in American Foreign Policy Towards Neutralist Africa By Kurt X. Metzmeier B.A., University of Louisville, 1982 A Thesis• Approved on April 26, 1989 (DATE) By the following Reading Committee: Thesis Director 11 ABSTRACT The emergence of an independent neutralist Africa changed the dynamics of the cold war. -

JULIET B. SCHOR Department of Sociology Ph: 617-552-4056 Boston College

JULIET B. SCHOR Department of Sociology ph: 617-552-4056 Boston College fax: 617-552-4283 531 McGuinn Hall email: [email protected] 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 PERSONAL DATA Born November 9, 1955; citizenship, U.S.A. POSITIONS Professor of Sociology, Boston College, July 2001-present. Department Chair, July 2005- 2008. Director of Graduate Studies, July 2011-January 2013. Associate Fellow, Tellus Institute. 2020-present. Matina S. Horner Distinguished Visiting Professor, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies, Harvard University, 2014-2015. Visiting Professor, Women, Gender and Sexuality, Harvard University, 2013. Visiting Professor, Yale School of Environment and Forestry, 2012, Spring 2010. Senior Scholar, Center for Humans and Nature, 2011. Senior Lecturer on Women’s Studies and Director of Studies, Women's Studies, Harvard University, 1997-July 2001. Acting Chair, 1998-1999, 2000-2001. Professor, Economics of Leisure Studies, University of Tilburg, 1995-2001. Senior Lecturer on Economics and Director of Studies in Women’s Studies, Harvard University, 1992-1996. Associate Professor of Economics, Harvard University, 1989-1992. Research Advisor, Project on Global Macropolicy, World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER), United Nations, 1985-1992. Assistant Professor of Economics, Harvard University, 1984-1989. Assistant Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University, 1983-84. Assistant Professor of Economics, Williams College, 1981-83. Research Fellow, Brookings Institution, 1980-81. 1 Teaching Fellow, University of Massachusetts, 1976-79. EDUCATION Ph.D., Economics, University of Massachusetts, 1982. Dissertation: "Changes in the Cyclical Variability of Wages: Evidence from Nine Countries, 1955-1980" B.A., Economics, Wesleyan University, 1975 (Magna Cum Laude) HONORS AND AWARDS Management and Workplace Culture Book of the Year, Porchlight Business Book Awards, After the Gig, 2020. -

U.S.-Cuban Talks in '63 Described

urinal states aeregate to the United Nations, the late Adlai 1 E. Stevenson, and to Ambas- -U.S.-CUBAN TALKS sador W. Averell Harriman. He added: "On Sept. 19, Harriman. told IN '63 DESCRIBED me he was "advmoz.esome' 0, 12,nilx.41 :/4 enough to favor the idea, but suggested I discuss it with Bob ,Book SeesKennedyC ut Kennedy because of-it5•polbtical on Castro Move for Ties iniplications. Stevenson, mein while, had mentioned it 'to.the President, who' approved t talking to Dr. Carlos 'Ledhuga, By HENRY RAYMONT the chief Cuban delegate; so A detailed account of Presi- long as I made it clear we were dent Kennedy's cautious but not soliciting discussions.", favorable response to overtures Terms Not Proposed by Premier Fidel Castro of Cu- Mr. Attwood suggested that ba for,, a resumption of diplo- the AdministratiCor never . ex- matic relations is disclosed in a plicitly proposed the terms of a. book to be published this month. settlement beyond . reiterating The secret diplomatic ex- its official position, that. Pre- changes between the two Gov- mier Castro should sever • all military ties with the Soviet ernments began in September, Union and Peking and renounce 1963, and ended with Mr. Ken- his proclaimed attempts to.sub- nedy's assassination. vert 'other Latin-American, gciv- Long withheld by fetiner ernnients. members of the Kennedy Ad: However, the book'' strongly suggests that the Kennedy Ad- WIUL ur. iscnuga, who ministration, the details of the ministration agreed . with his confidential talks appear in has- since been shifted to the estimate that a deal- was pos- Cuban Ministry of Culture, he "The Reds and the Blacks" by sible. -

The Chelmsfordian 2017 1

The Chelmsfordian 2017 1 2016 - 2017 The Chelmsfordian 2017 2 Contents 2 Introduction and Foreword 3 School Captain’s Report 4 Headmaster’s Report 7 Valete 8 Salvete 9 The Fallen 11 Otto Deutsch: A Eulogy 12 Assemblies 18 Miss Saigon Review 19 Essay: De Moribus 23 Essay: What Did Crusaders Hope to Achieve? 27 Combined Cadet Force 28 House Reviews 30 Sport Reviews 34 The KEGS Motto: An Exegesis 35 KEGS Hymnody and Music Review 36 Art Exhibition 2017 37 Monteverdi: 450 Years On 39 Editorials The Chelmsfordian 2017 3 Headmaster’s Introduction t gives me great pleasure to introduce this worked on it, and particularly to Mr Hugh year's Chelmsfordian magazine. I hope that Pattenden for his tireless work in leading and anybody reading this will find much of coordinating the venture. interest, and that it will also serve as part of Ithe historical record of King Edward VI Grammar School, Chelmsford. I am very grateful to all the Mr T. Carter contributors, to the editors Declan Hickey and Headmaster Oliver Parkes, and the other students who have Foreword ow in its 123rd year, the the tone of the school from all perspectives. It is Chelmsfordian continues to record clear from the diverse collection of reports; and celebrate the events of the historical records; reviews; assemblies and topical school. Whilst each edition will bear pieces, that KEGS has undergone significant Nthe greatest relevance to its contemporary changes in its transition into the twenty-first readership as a record of achievements over the century, but that the tone of the school remains year in drama, sport, and academics, it is important centred on an awareness of our past, respect for to recognise the historical importance of this others, and academic excellence. -

Ambassadorial Nominations

AMBASSADORIAL NOMINATIONS y 4 GOVERNMENT . r 7*/ 2- Storage Am j/Z- H E A R IN G S BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE EIGH TY -SE VE NT H CONG RESS FIRS T SESSION ON THE AMBASSADORIAL NOMINATIONS OF EDW IN O. REISCH- AUER—JAPAN, ANTHONY J. DREXEL BIDDLE —SPAIN, WILLIAM ATTWOOD—GUINEA, AARON S. BROWN—NICA RAGUA, J. KEN NET H GALBRAITH—INDIA, EDWARD G. STOCKDALE—IRELAND, WILLIAM McCORMICK BLAIR, JR.— DENMARK, JOH N S. RICE—TH E NETHERLANDS, AND KEN NETH TODD YOUNG—THAILAND MARCH 23 AND 24, 1961 Printed fo r the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 67590 WASHINGTON : 1961 v • * r* '» * -A : i m\S CO M M IT TEE ON FOR EIG N R ELA TIO N S J. W . F U L B R IG H T , A rk an sas, C h a ir m a n JO HN SPAR KM A N , Alab am a A L E X A N D E R W IL E Y , Wisc on sin H U B E R T H. H UM PH REY, M inne sota BO U RKE B. H IC KEN LO O PER, Iowa M IK E M A N SFIE LD , M on tana GEORGE D. A IK E N , Ve rm on t W AYN E M ORS E, Oregon HOMER E, CA PE H A R T , In di an a R U SS E L L B. LO NG , Lou isiana F R A N K CA RLS ON, K an sa s A L B E R T GO RE , Te nn essee JO HN J. -

We Love Big Brother: an Analysis of the Relationship Between Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four and Modern Politics in the United S

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-4-2018 We Love Big Brother: An Analysis of the Relationship between Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty- Four And Modern Politics in the United States and Europe Edward Pankowski [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Pankowski, Edward, "We Love Big Brother: An Analysis of the Relationship between Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four And Modern Politics in the United States and Europe" (2018). Honors Scholar Theses. 559. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/559 We Love Big Brother: An Analysis of the Relationship between Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four And Modern Politics in the United States and Europe By Edward Pankowski Professor Jennifer Sterling-Folker Thesis Adviser: Professor Sarah Winter 5/4/2018 POLS 4497W Abstract: In recent months since the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency of the United States in November 2016, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four has seen a resurgence in sales, and terms invented by Orwell or brought about by his work, such as “Orwellian,” have re- entered the popular discourse. This is not a new phenomenon, however, as Nineteen Eighty-Four has had a unique impact on each of the generations that have read it, and the impact has stretched across racial, ethnic, political, and gender lines. This thesis project will examine the critical, popular, and scholarly reception of Nineteen Eighty-Four since its publication 1949. Reviewers’ and commentators’ references common ideas, themes, and settings from the novel will be tracked using narrative theory concepts in order to map out an understanding of how the interpretations of the novel changed over time relative to major events in both American and Pankowski 1 world history. -

Table of Contents

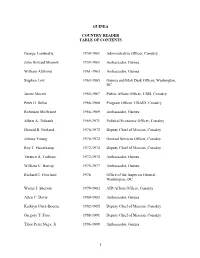

GUINEA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George Lambrakis 1959-1961 Administrative Officer, Conakry John Howard Morrow 1959-1961 Ambassador, Guinea William Attwood 1961-1963 Ambassador, Guinea Stephen Low 1963-1965 Guinea and Mali Desk Officer, Washington, DC James Moceri 1965-1967 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Conakry Peter O. Sellar 1966-1968 Program Officer, USAID, Conakry Robinson McIlvaine 1966-1969 Ambassador, Guinea Albert A. Thibault 1969-1971 Political/Economic Officer, Conakry Donald R. Norland 1970-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Johnny Young 1970-1972 General Services Officer, Conakry Roy T. Haverkamp 1972-1974 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Terence A. Todman 1972-1975 Ambassador, Guinea William C. Harrop 1975-1977 Ambassador, Guinea Richard C. Howland 1978 Office of the Inspector General, Washington, DC Walter J. Sherwin 1979-1982 AID Affairs Officer, Conakry Allen C. Davis 1980-1983 Ambassador, Guinea Kathryn Clark-Bourne 1982-1985 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Gregory T. Frost 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Tibor Peter Nagy, Jr. 1996-1999 Ambassador, Guinea 1 Joyce E. Leader 1999-2000 Ambassador, Guinea GEORGE LAMBRAKIS Administrative Officer Conakry (1959-1961) George Lambrakis was born in Illinois in 1931. After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Princeton University in 1952, he went on to earn his master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University in 1953 and his law degree from Tufts University in 1969. His career has included positions in Saigon, Pakse, Conakry, Munich, Tel Aviv, and Teheran. Mr. Lambrakis was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in June 2002. LAMBRAKIS: Bill Lewis was my immediate boss. And after two years in INR I was given my choice of three African assignments, I chose Conakry because it was a brand new post, and I spoke French. -

Fighting Back Against the Cold War: the American Committee on East-West Accord And

Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat from Détente A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Benjamin F.C. Wallace May 2013 © 2013 Benjamin F.C. Wallace. All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat from Détente by BENJAMIN F.C. WALLACE has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Chester J. Pach Associate Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT WALLACE, BENJAMIN F.C., M.A., May 2013, History Fighting Back Against the Cold War: The American Committee on East-West Accord and the Retreat From Détente Director of Thesis: Chester J. Pach This work traces the history of the American Committee on East-West Accord and its efforts to promote policies of reduced tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. This organization of elite Americans attempted to demonstrate that there was support for policies of U.S.-Soviet accommodation and sought to discredit its opponents, especially the Committee on the Present Danger. This work argues that the Committee, although largely failing to achieve its goals, illustrates the wide-reaching nature of the debate on U.S.-Soviet relations during this period, and also demonstrates the enduring elements of the U.S.-Soviet détente of the early 1970s. -

The Research Network

THETHE CONNECTEDCONNECTED LEARNINGLEARNING CVCV RESEARCHRESEARCH NETWORKNETWORK ReflectionsReflections onon aa DecadeDecade ofof EngagedEngaged ScholarshipScholarship WrittenWritten by: by: MizukoMizuko Ito Ito RichardRichard Arum Arum DaltonDalton Conley Conley KrisKris Guttiérez Guttiérez BenBen Kirshner Kirshner SoniaSonia Livingstone Livingstone VeraVera Michalchik Michalchik WilliamWilliam Penuel Penuel KylieKylie Peppler Peppler NicholeNichole Pinkard Pinkard JeanJean Rhodes Rhodes KatieKatie Salen Salen Tekinbaş Tekinbaş JulietJuliet Schor Schor JulianJulian Sefton-Green Sefton-Green S.S. Craig Craig Watkins Watkins withwith contributions contributions from: from: AliciaAlicia Blum-Ross Blum-Ross LindseyLindsey “Luka” “Luka” Carfagna Carfagna CrystleCrystle Martin Martin R.R. Mishael Mishael Sedas Sedas NatNat Soti Soti This edition of The Connected Learning Research Network: Reflections on a Decade of Engaged Scholarship is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Unported 3.0 License (CC BY 3.0) http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0/ ISBN-13: 978-0-9887255-6-0 Published by the Connected Learning Alliance. Irvine, CA. February 2020. Portions of this report were originally published in Ito et al. 2013. A full-text PDF of this report is available as a free download from https://clalliance.org/publications/ Cover art by Nat Soti Suggested citation: Ito, Mizuko, Richard Arum, Dalton Conley, Kris Gutiérrez, Ben Kirshner, Sonia Livingstone, Vera Michalchik, William Penuel, Kylie Peppler, Nichole Pinkard, Jean Rhodes, Katie Salen -

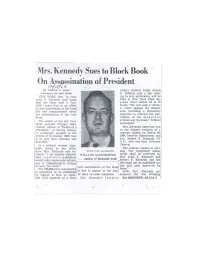

Mrs. Kennedy Sues to Block Book on Assassination of President by Andrew J

Mrs. Kennedy Sues to Block Book On Assassination of President By Andrew J. Glass foimer .Federal Judge Simon WWII/Wan Pod Staff Writer H Rifkind, said a suit seek- NEW YORK, Dec, 14—Mrs. ing to stop publication will be John F. Kennedy said today filed in New York State Su- that she must seek a "hor- preme Court within 48 to 72 rible" court trial in an effort hnurs. "We will seek a variety to halt publication of the book , of relief against the defend- she had commissioned about ants, including a temporary the assassination of her hus- injuction to restrain the pub- band. lication of the magazine The widow of the late Pres- reticles and the book," Rifkind ident accused William Man- announced. chester, author of "Death• of a Mrs. Kennedy based her suit President," of having written on the alleged violation of a "a premature account of the contract signed on March 26, events of November, 1963, that 1964, between Manchester and is in part both tasteless and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (D- distorted." N.Y.), who was then Attorney In a bitterly worded state- General. ment issued by her office The contract stated, in part, here, Mrs. Kennedy also de- Mitted PresK International that "the completed manu- clared: "I am equally shocked WILLIAM MANCHESTER script shall be reviewed by that reputable publishers Mrs. John F. Kennedy and . .. author of Kennedy book would take commercial advant- Robert F. Kennedy and the age of (Manchester's) failure text shall not be published un- to. keep his word." Hart serialization of the book less and until approved by The 350,000-word manuscript them." is scheduled to be published is due to appear in the Jan.