Eric Ewazen's Trio for Clarinet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Performer's Analysis of Eric Ewazen's Sonata for Trumpet and Piano

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 A Performer's Analysis of Eric Ewazen's Sonata for Trumpet and Piano Joseph Daniel McNally III University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation McNally, Joseph Daniel III, "A Performer's Analysis of Eric Ewazen's Sonata for Trumpet and Piano" (2008). Dissertations. 1110. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1110 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi A PERFORMER'S ANALYSIS OF ERIC EWAZEN'S SONATA FOR TRUMPET AND PIANO by Joseph Daniel McNally, A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY JOSEPH DANIEL MCNALLY, 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi A Performer's Analysis of Eric Ewazen's Sonata for Trumpet and Piano by Joseph Daniel McNally, III Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT A PERFORMER'S ANALYSIS OF ERIC EWAZEN'S SONATA FOR TRUMPET AND PIANO By Joseph Daniel McNally, III May 2008 Eric Ewazen is a prolific composer whose works are becoming standard repertoire for not only trumpet players but also for brass quintets, soloists, and wind ensembles alike. -

Eric Ewazen Was Born in 1954 in Cleveland, Ohio. Receiving a B.M. at the Eastman School of Music, and M.M

Eric Ewazen was born in 1954 in Cleveland, Ohio. Receiving a B.M. At the Eastman School of Music, and M.M. and D.M.A. degrees from The Juilliard School, his teachers include Milton Babbitt, Samuel Adler, Warren Benson, Joseph Schwantner and Gunther Schuller. He is a recipient of numerous composition awards and prizes. His works have been commissioned and performed by many soloists, chamber ensembles and orchestras in the U.S. and overseas. His works are recorded on Summit Records, d'Note Records, CRS Records, New World, Clique Track, Helicon, Hyperion, Cala, Albany and Emi Classics. Two of his solo CD's featuring his chamber music are available on Well-Tempered Productions. Three additional solo CD's, one featuring his orchestral music, another his music for low brass instruments, and a third, his music for string orchestra, are available on Albany Records. A sixth solo Cd of his music for percussion is available on Resonator Records. New World Records has released his concerto for brass quintet, "Shadowcatcher" with the American Brass Quintet and The Juilliard Wind Ensemble, conducted by Mark Gould of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Individual works of Eric Ewazen have recently been released by the Ahn Trio, Julie Giacobassi of the San Francisco Symphony, Charles Vernon of the Chicago Symphony, Koichiro Yamamoto of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Ronald Barron of the Boston Symphony, Doug Yeo of the Boston Symphony, Steve Witser of the Cleveland Orchestra, Joe Alessi and Philip Smith of the New York Philharmonic, the Horn Section of the New York Philharmonic, the Summit Brass Ensemble and the American Brass Quintet. -

School of Music Compact Presents O\SC ~~E 200 5 UNIVERSI1Y OFWASHINGTON 2.-11 CONCERT BAND

University of Washington' 2004-2005 ' School of Music COMPAcT Presents O\SC ~~e 200 5 UNIVERSI1Y OFWASHINGTON 2.-11 CONCERT BAND UNIVERSI1YOFWASHINGTON CHAMBER WINDS Timothy Salzman, conductor UNIVERSI1YOFWASHINGTON SYMPHONIC BAND Dr. 1. Bradley McDavid, conductor Featuring the music ofcomposer-in-residence ERIC EWAZEN and a world premiere of HABoo by GREGORYYOUTZ - 7:30 PM February 17, 2005 MEANY THEATER .~ .... ~.. ,... ,'" -'f;ti'~'" \ ' ,;. : '" '., . 't,., . .. ;::i .......... UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON CONCERT BAND CD \4;,~P-\ .::J. /; if r ;. - ill FLOURISH FOR GWRloUSJOHN(1957) .............. RALPH VAUGHAN WIU.IAMS (1872-1958) Matthew Kruse, conductor G~ ONA HYMNSONG OF PHIliP BliSS (1989) .........~'~3 :.................... DAVID HOLSINGER (b. 1945) Ben Clark, conductor ffi RE/OUISSANCE (1983) .............?.:}.'f ......................:............. JAMES CURNOW (b. 1943) Melia McNatt, conductor B3 CCJ).1i\~n I 5ViJz..WlGlvl1- E'WCtUv) . tsJ1YMNFOR THE LOSTAND THE LIVING (2002) .........<].:.':f.1............. ERIC EWAZEN (b. 1954) Mitchell Lutch, conductor UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON CHAMBER WINDS Timothy Saizman, conductor CDILj,gl5"' ill DOWN A RIVER OF TIME, a Concerto for Oboe and Chamber Winds (200 I). ERIC EWAZEN II. ...and sorrows It;;; '-t 8 Ill. ...and memories of tomorrow Jennifer Muehrcke, oboe, UW student soloist @ C<.:.JYt\ W\,MI\1'7 I (2"WC{ Z£.-v\ UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON SYMPHONIC BAND Dr. J. Bradley McDavid, conductor l4J C.O'WHt1t\..f,.,.,1T." Wl cVCI VI cf ZO'O-=j 13 HABOO (2005) ........................................... :.......................... GREOORY YOUTz (b. 1956) @LEGACY............. r.1.'1.r.e ........................................................................... ERIC EWAZEN I. ... ofa Fortress over a River Valley Born in 1954 in Cleveland, Ohio, Composer-in-Residence Erie Ewazen studied under Samuel Adler, Milton Babbitt, Warren Benson, Gunther Schuller and Joseph Schwantner at the Eastman School of Music, Tan glewood and The Juilliard School where he has been a member of the faculty since 1980. -

Downloads Are Also Available at Cdbaby.Com and György Ligeti and Used for Itunes

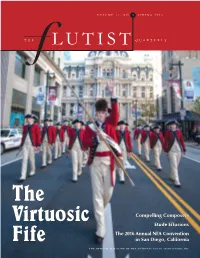

VOLUME 41, NO. 3 SPRING 2016 THE LUTIST QUARTERLY The Virtuosic Compelling Composers Etude Effusions The 2016 Annual NFA Convention Fife in San Diego, California THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION, INC CAROL WINCENC PLAYS BURKART BURKART.COM Carol_FullPageAd_FINISH.indd 1 6/2/15 7:34 PM Pearl’s Alto flute is a truly monumental instrument, The only Alto flute on the market to have our world renowned Pinless mechanism and One Piece Core Bar construction. In addition, the hand position is extremely comfortable, and the headjoint is highly responsive with amazing projection. The exceptionally efficient and highly dependable mechanism is complimented by Pearl’s KEVIN WILLIAMS devotion to exact intonation, wide THE REGIMENT HORNS dynamic spectrum and tonal flexibility. Only from Pearl. Alto Flutes are available with an All Sterling Tube (Model 207) Sterling Silver headjoint (Model 206) or with a Silver Plated headjoint with Sterling Silver Lip Plate (Model 201). Model PFA201SU Shown Above. Available with Straight, Curved, or both headjoints SPRING Table of Contents 2016 The Flutist Quarterly Volume 41, No. 3 Pearl’s Alto flute is a truly monumental instrument, The only Alto flute on the market to have our world renowned Pinless mechanism and One Piece DEPARTMENTS Core Bar construction. In addition, 13 From the President the hand position is extremely comfortable, 15 From the Editor and the headjoint is highly responsive with amazing projection. The exceptionally 16 High Notes efficient and highly dependable 45 Across the Miles mechanism is complimented by Pearl’s KEVIN WILLIAMS devotion to exact intonation, wide 48 From the 2016 Convention 20 30 40 THE REGIMENT HORNS dynamic spectrum and Program Chair tonal flexibility. -

Two Selected Works for Solo Trumpet Commissioned by The

TWO SELECTED WORKS FOR SOLO TRUMPET COMMISSIONED BY THE INTERNATIONAL TRUMPET GUILD: A STRUCTURAL AND PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS WITH A HISTORY OF THE COMMISSION PROJECT, WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY ARUTUNIAN, HAYDN, FASCH, CHAYNES AND OTHERS Gary Thomas Wurtz, B.M.E., M.M.E. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August, 2001 APPROVED: Leonard A. Candelaria, Major Professor Deanna Bush, Minor Professor Graham Phipps, Committee Member Thomas Clark, Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Wurtz, Gary Thomas, Two selected works for solo trumpet commissioned by the International Trumpet Guild: a structural and performance analysis with a history of the commission project, with three recitals of selected works by Arutunian, Haydn, Fasch, Chaynes and others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2001, 154 pp., 64 examples, 3 figures, bibliography, 90 titles, 1 appendix. An historical overview of the ITG commission project is presented, as well an analysis of formal organization and significant features for two of the commissioned works: Sonata for Trumpet and Piano by Norman Dello Joio and Sonata for Trumpet and Piano by Eric Ewazen. Complete histories of all works and information concerning their premieres is chronicled. The degree of difficulty of each composition is assessed through an investigation of tessitura, range, melodic contour, endurance factors, articulation, fingerings, and technical features of the accompaniment -

17T ANNUAL PACIFIC NORTHWEST MUSIC FESTIVAL

University of Washington 2004-2005 School ofMusic COM -c Presents the blSc t3 y Z-~5 17t ANNUAL 2-g PACIFIC NORTHWEST MUSIC FESTIVAL FESTIVAL C OORDINATOR M ITCHELL LUTCH GUEST CLINICIANS FRANK BATTISTI DAVID FuLLMER GARWOOD WHALEY JUNIOR HIGH/MIDDLE SCHOOL CONCERT BANDS Monday, February 7, 2005 'v ~ HIGH SCHOOL CONCERT BANDS Tuesday, February 8, 2005 UNIVERSITY OF W ASIDNGTON WIND ENSEMBLE Timothy Salzman, conductor OJ . ! VI BOGORODlTSE DEVO (J 915) ...................'2.2-0 ~ .................................. SERGEI RACHMANINOFF (1873-1943) MOTOWN METAL (1994) ...............~.: . ~.................................... MICHAEL DAUGHERTY (b. 1954) I . CONCERTO FOR TRUMPET (1950) ........j .................................. A LEXANDER ARUTUNlAN (b. 1920) Brian Chinn, trompet, UW student soloist DOWN A RiVER OF T TME, . -:;-. 1\ A CONCERTO FOR OBOE AND CHA MBER WINDS (2001) ............................... ERIC EWAZEN 111. ... and memories o/tomorrow (b. 1954) Jennifer Muehrcke, oboe, UW student oloist ? ~,) REDLINE TANGO (.004) ....................................................................... .. .JOHN MAcKEY (b. 1973) ( Lj SECOND SUITE IN F FOR MiLITARY B AND (1922) .......... :::........................ G USTAV IIOLST I. March (1874-1934) ll. Song Witholll Words Ill. Song 0/ the Blacksmith IV. Fantasia on 'The Dargason I Frank Battisti, guest onduclor 2005 Pacific Northwest Music Festival Monday. Febnlary 7, 2005 JUNIOR HIGH/MIDDLE SCHOOL CONCERT BAND DIVL lON School Warm-up Performancel Clinic ECKSTEIN MS,lntenn diate Band 7:30 -

2016-2017 New Music Festival

Eleventh Annual New Music Festival 3 events I 6 world premieres I 50 performers Eric Ewazen, Composer-in Residence Lisa Leonard, Director January 21 - January 23, 2017 2016-2017 Season SPOTLIGHT I: YOUNG COMPOSERS Friday, January 23 at 7:30 p.m. Reminiscent Waters (2016) Matthew Carlton (b. 1992) Sodienye Finebone, tuba Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Selections from String Quartet No.1 (2016) Evan Musgrave World Premiere (b. 1995) I. Grave II. Presto Katherine Baloff, Yordan Tenev, violins Andrew Baloff, viola Stephanie Barrett, cello NIcht Eine Kartoffel Tondichtung für Viola und Reciter (2016) World Premiere Alfredo Cabrera (b.1996) Text: Joseph Stroud Cameron Hewes, reciter Miguel Sonnak, viola Serenade for Strings (2016) Trevor Mansell World Premiere (b.1999) Natalia Hildalgo, Virginia Mangum, violins Kayla Williams, viola Trace Johnson, cello August Berger, bass INTERMISSION Suite from the film “The Life and Times of Merle Singer” (2016) World Premiere Matthew Carlton I. Journey to Duluth II. Divertimento III. Dave’s Story IV. The Lake Jared Harrison, flute; Walker Harnden, oboe Jackie Gillette, clarinet; Erika Andersen, bassoon James Currence, French horn; Yana Lyashko, harp; Soo Jung Kwon, celeste Yasa Poletaeva, Benita Dzhurkova, violins Kayla Williams, viola Trace Johnson, cello Sonata di Battaglia for Wind Sextet (2016) Anthony Trujillo World Premiere (b.1995) Jared Harrison, flute/piccolo Teresa Perrin, flute John Weisberg, oboe Cameron Hewes, clarinet Sean Murray, French horn Michael Pittman, bassoon In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni for String Quintet (2016) World Premiere Alfredo Cabrera I. Lovers at Twilight II. Demons and Joropo III. Torches 1 IV. Fireflies V. Torches 2 VI. -

Eric Ewazen's Concerto for Marimba, Orchestrated for Chamber

LASLEY, MICHAEL LEE, D.M.A. Eric Ewazen’s Concerto for Marimba, Orchestrated for Chamber Ensemble: A Performance Edition. (2008) Directed by Dr. Cort A. McClaren. 267 pp. Numerous concertos have been written for the marimba since 1940, the year that the first marimba concerto was written by Paul Creston. Some of these concertos are available with multiple accompaniments. The most frequently performed marimba concerto, Ney Rosauro’s Concerto for Marimba, has been documented as having more than half of the performances with piano and percussion ensemble over that of the original string orchestra accompaniment. One may infer that the increased availability of various accompaniments encourages more performances of marimba concertos. Performers may have more opportunities to perform with smaller ensembles rather than orchestras, the traditional venue for concerto performance. Although piano reductions are often an accepted alternative, such a venue may yield a loss of the original intent of the composition. Accompaniments including wind ensemble, reduced strings, and chamber settings may provide options that convey the original intent of the composer more closely than a piano reduction. American composer Eric Ewazen has a vast output of concertos for a number of different instruments and instrument combinations. Most of Ewazen’s concertos are available with multiple accompaniments. Ewazen composed the Concerto for Marimba and String Orchestra in 1999 for marimbist She-e Wu. The concerto has several published accompaniments scored by Ewazen and others. A variety of orchestrations of Ewazen’s marimba concerto may create additional performance opportunities outside of those with orchestral accompaniment. The result of this study is a chamber ensemble orchestration of Eric Ewazen’s Concerto for Marimba and String Orchestra scored for nine wind players and one contrabass. -

And Often the 'Highlight of the Program'

For this album of American music, ABQ has invited the esteemed music historian, Michael Grace, to provide liner notes. Dr. Grace is a professor at Colorado College and writes program notes for the Colorado College Summer Music Festival. An expert on music and art from many periods, his course topics include Renaissance culture, American music, and 20th Century music. A 'modern day master' and often the 'highlight of the program' (The New York Times), Robert Paterson's music is praised for its elegance, wit, structural integrity, and a wonderful sense of color. Paterson was named The Composer of The Year by the Classical Recording Foundation with a performance and celebration at Carnegie's Weill Hall in 2011. His music has been on the Grammy® ballot yearly, and his works were named ‘Best Music of 2012' on National Public Radio. His works have been played by the Louisville Orchestra, Minnesota Orchestra, American Composers Orchestra, Austin Symphony, Vermont Symphony, BargeMusic, the Albany Symphony Dogs of Desire, among others. Paterson’s choral works were recorded by Musica Sacra and Maestro Kent Tritle, with a world premiere performance at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. Notable awards include the Utah Arts Festival Award, the Copland Award, ASCAP Young Composer Awards, a three year Music Alive! grant from the League of American Orchestras and New Music USA, and yearly ASCAP awards. Fellowships include Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, and the Aspen Music Festival. Paterson holds degrees from the Eastman School of Music (BM), Indiana University (MM), and Cornell University (DMA). He regularly gives master classes at colleges and universities, including the Curtis Institute of Music, New York University, and the Cleveland Institute of Music. -

Samuel Adler Collection, Box 8, Folder 19, Sleeve 5

SAMUEL ADLER PAPERS (1999–2018 Gifts) RUTH T. WATANABE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SIBLEY MUSIC LIBRARY EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Processed by Gail E. Lowther, Spring 2019 1 Photograph of Joseph Polisi and Samuel Adler, at induction to the American Classical Music Hall of Fame (2008). From Samuel Adler Collection, Box 8, Folder 19, Sleeve 5. Photograph of Samuel Adler conducting an Eastman Ensemble. Photograph attributed to Louis Ouzer, from ESPA 30-7 (8x10). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of Collection . 4 Description of Series . 7 INVENTORY Series 1: Sheet Music Sub-series A: Original Compositions . 9 Sub-series B: Transcriptions and Edited Music . 18 Series 2: Papers Sub-series A: Correspondence . 18 Sub-series B: Papers . 144 Series 3: Publicity and Press Materials Sub-series A: Concert Programs and Publicity . 149 Sub-series B: Press Clippings . 152 Sub-series C: Scrapbook . 153 Series 4: Audio-Visual Materials . 153 Series 5: Oversized Sub-series A: Oversized Sheet Music . 155 Sub-series B: Oversized Papers . 156 Sub-series C: Oversized Publicity and Press Materials . 157 3 DESCRIPTION OF COLLECTION Shelf location: C4B 9,7 – 10,3 Extent: 30 linear feet Biographical Sketch Photograph from ESPA 30-10 (8x10). Samuel Adler was born on March 4, 1928, to American parents living in Mannheim, Germany. In 1939, his father, who had served as cantor in the Mannheim Synagogue, accepted a position in Worcester, Massachusetts. There, in Boston, the younger Adler studied composition with Herbert Fromm and later at Boston University with Karl Geiringer, Hugo Norden, and Paul Pisk. After completing a bachelor’s degree at Boston in 1949, he entered Harvard University, where he studied under Irving Fine, Walter Piston, and Randall Thompson. -

Flight for Wind Ensemble

ERIC EWAZEN for Wind Ensemble Perusal Perusal FULL SCORE Eric Ewazen Flight for Wind Ensemble Commissioned in Celebration of the 100th Anniversary of Powered Flight INSTRUMENTATION 2-FULL SCORE 3-1st TRUMPET in Bb 1-DOUBLE BASS 1-PICCOLO 3-2nd TRUMPET in Bb 1-TIMPANI 6-1st FLUTE 3-3rd TRUMPET in Bb 2-1st PERCUSSION: Bell Tree, Tam- tam, Snare Drum, Crash and 6-2nd FLUTE 1-1st HORN in F 1-1st OBOE 1-2nd HORN in F Suspended Cymbals, Tom-toms 1-2nd OBOE 1-3rd HORN in F 2-2nd PERCUSSION: Bells, Crotales, Chimes, Snare Drum, 4-1st CLARINET in Bb 1-4th HORN in F Wood Blocks, Suspended Cymbals 4-2nd CLARINET in Bb 2-1st TROMBONE 1-3rd PERCUSSION: Vibraphone 4-3rd CLARINET in Bb 2-2nd TROMBONE 1-4th PERCUSSION: Marimba 2-BASS CLARINET IN Bb 2-BASS TROMBONE 1-CONTRA ALTO or CONTRA 2-EUPHONIUM in Treble Clef BASS CLARINET 3-EUPHONIUM in Bass Clef 1-1st BASSOON 6-TUBA 1-2nd BASSOON 2-1st ALTO SAXOPHONE in Eb 2-2nd ALTO SAXOPHONE in Eb 2-TENOR SAXOPHONE in Bb 1-BARITONE SAXOPHONE in Eb I. A View from the Heavens ................................ ........... 3 II. Above the Storm and the Fray ................................ 51 III. Through Azure Skies Toward a Golden Sun ..... 103 Duration: Approx. 19 Minutes Perusal (I. 5:45, II. 6:30, III. 6:15) Copyright © 2004 Southern Music Company (ASCAP). International Copyright secured. All rights reserved. Program Notes Flight, was commissioned in 2001 and is gratefully dedicated to the USAF Heritage of America Band and its conductor, Major Larry Lang, for the 100th anniversary of powered flight, December 17, 2003. -

ERIC EWAZEN Piano ERIC EWAZEN ERIC ERIC EWAZEN MUSIC for BASS TROMBONE BASS for MUSIC MUSIC for BASS TROMBONE

YOSSI ITSKOVICH BASS TROMBONE MEMBERS OF THE TENERIFE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERIC EWAZEN PIANO ERIC EWAZEN ERIC ERIC EWAZEN MUSIC FOR BASS TROMBONE BASS FOR MUSIC MUSIC FOR BASS TROMBONE WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1599 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2015 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. ERIC EWAZEN TROY1599 ERIC EWAZEN MUSIC FOR BASS TROMBONE MUSIC FOR BASS TROMBONE Quintet for Bass Trombone & Strings Trio for Horn, Bass Trombone & Piano 1 Allegro Ritmico [4:01] 8 Lento - Allegro Agitato [5:57] 2 Moderato [5:40] 9 Andante [6:39] 3 Allegro Molto [3:17] 10 Allegro [5:37] 4 Fugue [3:09] Inez Gonzales, HORN | Yossi Itskovich, BASS TROMBONE Juan Carlos Gómez & Eduardo Langarica Cavani, VIOLINS Eric Ewazen, PIANO Sviatoslav Belonogov, VIOLA | Gabrielle Zanetti, CELLO Yossi Itskovich, BASS TROMBONE 11 Ballade [12:55] Yossi Itskovich, BASS TROMBONE | Eric Ewazen, PIANO Trio for Tenor Trombone, Bass Trombone & Piano 5 Andante Teneremante [6:10] 12 Pastorale for Trumpet, Bass Trombone & Piano [7:44] 6 Barcarolle [8:00] Ingrid Rebstock, TRUMPET MUSIC FOR BASS TROMBONE [ ] Yossi Itskovich, BASS TROMBONE | Eric Ewazen, PIANO 7 Caprice 4:21 Dede Decker, TENOR TROMBONE Yossi Itskovich, BASS TROMBONE | Eric Ewazen, PIANO Total Time = 73:54 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1599 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TROY1599 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2015 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL.