Freedman, Mark Stewart Follow—Up of Physical Education Graduates Froh a Teacher Preparation Program: a Descriptive Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

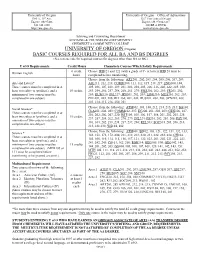

University of Oregon U of O Basic Courses

University of Oregon University of Oregon – Office of Admissions 1385 E. 13th Ave. 1217 University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97406 Eugene, OR 97304-1217 541-346-1000 800-BE-A-DUCK https://uoregon.edu [email protected] Advising and Counseling Department ADVISING & COUNSELING DEPARTMENT CHEMEKETA COMMUNITY COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF OREGON (Eugene) BASIC COURSES REQUIRED FOR ALL BA AND BS DEGREES (See reverse side for required courses for degrees other than BA or BS.) U of O Requirements Credit Hours Chemeketa Courses Which Satisfy Requirements 6 credit Choose WR121 and 122 (with a grade of C- or better) WR121 must be Written English hours completed before transferring. Choose from the following: ART201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 289; Arts and Letters* ASL211, 212, 213; COMM100, 111, 112, 115, 218, 219; ENG100, 104, These courses must be completed in at 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 201, 202, 204, 205, 206, 216, 220, 222, 245, 250, least two subjects (prefixes), and a 15 credits. 253, 254, 256, 257, 258, 260, 261, 275; FMS201, 202, 203; FR201, 202, minimum of two courses must be 203; HUM120; JNL227; JPN201, 202, 203; LING210; MUS201, 202, 203, completed in one subject. PHL201, 203, 206; REL160, 201, 202; RUS201, 202, 203; SPN201, 202, 203, 214, 215, 216, 250, 251 Choose from the following: ATH102, 103, 180, 212, 214, 215, 231; BA101; Social Science* CLA201, 202, 203; COMM212, 237; EC200, 201, 202, 203; GEG106, 107, These courses must be completed in at 201, 202, 206, 207, 220; HST104, 105, 106, 157, 158, 201, 202, 203, 228, least two subjects (prefixes), and a 15 credits. -

![Address: Biology Department Gilbert Hall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: (650) 725-2460 [Lab 723-0881]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8328/address-biology-department-gilbert-hall-stanford-university-stanford-ca-94305-phone-650-725-2460-lab-723-0881-418328.webp)

Address: Biology Department Gilbert Hall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: (650) 725-2460 [Lab 723-0881]

Curriculum Vitae Russell Dawson Fernald Address: Biology Department Gilbert Hall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: (650) 725-2460 [Lab 723-0881] Education: Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA, B.S., 9/59-6/63 University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, Ph.D., 9/63-1/68 (Biophysics) Max-Planck-Institut fur Psychiatrie, Munich, West Germany, Post-doctoral Fellowship, 1969-71 (Neurophysiology) Academic Awards: Ford Foundation Pre-doctoral Fellowship, 1963-64 NIH Pre-doctoral Fellowship, 1964-68 Max Planck Institut Post-doctoral Fellowship, 1969-71 NIH Research Career Development Award, 1978-83 NIH Fogarty Senior International Fellowship, 1985-86 (Medical Research Council, London) Hilgard Visiting Professorship, Stanford University, 1988-89 Benjamin Scott Crocker Professor of Human Biology, Stanford University, 1994- Javits Neuroscience Investigator Award, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 1999-2006 Fellow-American Association for Advancement of Science, 2003 Rank Prize in Vision/Opto-electronics, 2004 Javits Neuroscience Investigator Award, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2007-2014 Mimi and Peter Haas Fellow in Undergraduate Education, 2003- American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Elected 2011 R.D. Fernald, Curriculum vita p.2 Professional Experience: Doctoral student (with Dr. George Gerstein), University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, 1963-68. Max-Planck Postdoctoral Fellow (with Professor Otto Creutzfeldt), Max-Planck- Institute for Psychiatry, Munich, W.Germany, 1969-71. Institute Scientist, Max-Planck-Institute for Behavioral Physiology, (with Professor Konrad Z. Lorenz), Seewiesen, W. Germany, 1971-73. Staff Scientist, Max-Planck-Institute for Behavioral Physiology, Seewiesen, W. Germany, 1973-76. Assistant Professor, Department of Biology, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, 1976-80. Associate Professor, Department of Biology and Institute of Neuroscience, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, 1980-86. -

Athletics Department Overview

ATHLETICS DEPARTMENT OVERVIEW 1 FY14 REVENUE OVERVIEW ∆ From % Revenues By Category FY14 % of Budget FY13 Change Gifts/Donations 29,907,000 32.2% (1,093,000) ‐3.5% Ticket Sales 25,606,000 27.5% 456,500 1.8% PAC 12/NCAA 18,756,796 20.2% 328,246 1.8% Sponsorship, Royalties 6,621,600 7.1% 925,600 16.3% Food & Beverage 4,359,000 4.7% (342,975) ‐7.3% Ticket‐Related Fees 3,240,000 3.5% (461,423) ‐12.5% Incidental Fees 1,715,099 1.8% 191,099 12.5% Miscellaneous 1,088,000 1.2% (302,000) ‐21.7% Rentals 535,000 0.6% 189,000 54.6% Guarantees 415,000 0.4% 405,000 4050.0% Special Events 395,000 0.4% (81,613) ‐17.1% Parking 274,000 0.3% (175,000) ‐39.0% Interest Income 100,000 0.1% 25,000 33.3% Lottery 0 0.0% (918,207) ‐100.0% Total 93,012,495 100.0% (853,772) ‐0.9% 2 FY2014: Total Revenue = $93M Revenues By Type Food & Beverage 4.69% Broadcast, Sponsorship Gifts/Donations 7.12% 32.15% PAC 12/NCAA 20.17% Ticket Sales 27.53% 3 FY2014: Total Revenue = $93M REVENUES BY SPORT/AREA General Support 4.7% Outside Events 1.2% Legacy Fund 12.4% Other Sports 2.8% Men's Basketball 12.4% Football 66.6% 4 FY14 EXPENSE OVERVIEW % OF % EXPENSE BY TYPE FY14 ∆ FROM FY13 BUDGET CHANGE Salaries/Benefits 32,429,120 34.9% (8,294) 0.0% Debt Service 19,126,984 20.6% (1,609) 0.0% Scholarships 10,406,200 11.2% 505,776 5.1% Support Operations 10,034,607 10.8% (875,839) ‐8.0% Sport Operations 8,674,947 9.3% 441,443 5.4% Facilities/Event Operations 7,427,192 8.0% 233,035 3.2% Campus Assessments 2,289,793 2.5% 311,239 15.7% Game Guarantees 1,721,540 1.9% (1,510,060) ‐46.7% Reserve/Contingencies -

Curriculum Vitae EVAN N. SHENKIN Department of Sociology Email

Curriculum Vitae EVAN N. SHENKIN Department of Sociology Email: [email protected] University of Alaska Phone: 541.579.1207 Anchorage AK, 99508 Office: SSB 364 PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2019 Pre-Professoriate Fellow, Department of Sociology, University of Anchorage, Alaska 2019 Instructor, Department of Sociology, Oregon State University, Oregon 2018 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Willamette University, Oregon EDUCATION 2018 Ph.D., Sociology, University of Oregon 2014 M.A., Sociology, University of Oregon 2009 M.A., International Studies, University of Oregon 2009 Graduate Certificate, Not-For-Profit Management, University of Oregon 2006 B.A., Cultural Anthropology, University of Oregon 2003 A.A.O.T., Lane Community College TEACHING EXPERIENCE 8/26/2019 - present Environmental Activism & Indigenous Land Rights 4/1/2019 - 6/14/2019 Social Issues and Problems, Oregon State University 1/22/2018 - 5/10/19 Sociology of Education, Willamette University 9/24 - 12/11/2018 Development & Social Change in Latin America 8/20/18 - 8/29/2018 Introduction to International Issues 8/2018 - 9/2018 Climate Change and Development in the Anthropocene 6/2018 - 7/2018 Introduction to Sociology 3/2018 - 6/2018 Urban Sociology 1/2018 - 3/2018 Systems of War and Peace 9/2017 - 12/2017 Community, Environment and Society 7/2017 - 8/2017 Social Inequality 6/15 - 7/15 2009 Global Environmental Issues TEACHING ASSISTANT / ADVISING EXPERIENCE 9/2015 - 6/2017 Introduction to Sociology, Social Inequality, Sociology of Work and Occupations, Community, -

Codeof Conduckt

UNIVERSITY OF OREGON ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT The UO Athletic Department is dedicated to MEN’S BASKETBALL* providing a safe and enjoyable experience for all Oregon Men's Basketball tickets are generally distributed by guests and athletes at all events. With this goal in home stand (usually two games at a time). A diagram of McArthur mind, we ask that everyone observe the following Court is included in this brochure showing student seating sec- Code Of guidelines. tions (indicated by gray areas). For the majority of games, a total of 1,323 tickets per game are available for UO students. For games Respect all attendees and refrain from disruptive behavior, including foul language, obscene gestures or messages, and physical harm contested during the winter break, student seating will be limited ConDUCKt or threats. to section 10. Sit only in your ticketed seats and be prepared to show your ticket GOOD SPORTS INITIATIVE when requested. *Note: standing on seats is not allowed and may result in loss of Comply with requests from event staff regarding stadium policies student seating. and emergency procedures. Use tobacco only in designated areas. The 2009-10 home schedule will be available at a later date on GoDucks.com. In the event that the distribution schedule results The UO values the support of all DAF donors, season ticket holders, students and guests visiting our facilities each season and thanks you in advance for in distribution of football and men’s basketball tickets on the being a good egg. If you observe any violations of stadium guidelines, please same day, football shall begin distribution on the Sunday prior to immediately contact the nearest event staff or TEXT ‘BAD DUCK’ to call GODUCKS (4638257). -

Global Supply Chain Management/Transportation Building a Global Network of Scholars and Educators Phase II

Global Supply Chain Management/Transportation Building a Global Network of Scholars and Educators Phase II Final report By Paul Hong, Ph.D., CMA Professor Information Operations Technology Management Department College of Business and Innovation The University of Toledo Prepared for The University of Toledo University Transportation Center and the U.S. Department of Transportation April 2012 DISCLAIMER The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. From March 8-10, The University of Toledo faculty (Mark Vonderembse, Paul Hong, Monideepa Tarafdar, Udayan Nandkelyor, Sachin Modi, David Dobrzykowski) and two doctoral students (Ryan Skiver and Vincent Whitelock) have attended the 5th Conference on International Supply Chain Management in Tokyo, Japan. Financial support of UT/UTC grants ($12,000 +) made this conference quite successful in a number of ways. This conference has achieved the following objectives. For more details, please check the 5th International Supply Chain Management Symposium and Workshop . First, initially there was a concern about the safety issues of having this international conference in Tokyo, Japan since serious natural disaster and nuclear reactor accidents in Fukushima took more than several months to resolve. However, with the cooperation of Japanese government and University of Tokyo, the issues were adequately addressed and thus this International conference in Tokyo occurred as planned. -

Anna E. Skubel 621 Commonwealth Ave. Boston, MA 02215 (703) 975-2516

Anna E. Skubel 621 Commonwealth Ave. Boston, MA 02215 (703) 975-2516 Education Boston University, Wheelock College of Education and Human Development, Boston, MA Doctor of Philosophy in Counseling Psychology and Applied Human Development Applied Human Development Track Expected May 2024 Vanderbilt University, Peabody College, Nashville, TN Master of Education in Child Studies, May 2018 Clinical and Developmental Research Track New York University, New York, NY Bachelor of Arts in Politics, cum laude, January 2015 Minors in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Studies and History Research Experience Doctoral Research Assistant at Boston University 2019-Present Boston University, Boston, MA PI: Dr. Tina Durand • Conduct and write literature review on LatCrit and Puerto Rican ethnic identity for manuscript on qualitative study regarding school context and identity for Puerto Rican middle schoolers. Doctoral Research Assistant for The Kids FACE FEARS Study 2019-Present Boston, MA PI: Dr. Lisa Fortuna and Dr. Michelle Porche • Format and translate multiple workbooks for a research-based, anxiety intervention program (Cool Kids Program) from English into Spanish for a randomized- controlled, multi-site, PCORI-funded project. Doctoral Research Assistant for the Center for Promise 2018- Present Boston University, Boston, MA PI: Dr. Jonathan Zaff • Conduct qualitative and quantitative research projects highlighting youth perspectives on a range of education and development topics, such as school reengagement, social and emotional learning, and work-force development. • Create research questions, semi-structured interview protocols, surveys, and coding schemes for research projects. • Collect data from youth and adults by leading focus groups and individual interviews. • Analyze qualitative data using open and axial coding methods. -

Andrew H. Morris Curriculum Vitae

Andrew H. Morris Curriculum vitae Contact 335 Pacific Hall 860-670-4130 Information Eugene, OR 97403 [email protected] Education Ph.D. University of Oregon, Biology Expected 2021 M.S. Penn State University, Soil Science 2017 B.S. Cornell University, Plant Sciences 2014 Research NSF Graduate Research Fellow 2016 to present Appointments ARCS Scholar 2017-2020 Graduate Employee, University of Oregon 2017-2018 Graduate Research Assistant, Penn State University 2015-2017 Research Assistant, University of Delaware 2015 Publications 1. Morris, A. H., Isbell, S. A., Saha, D., and Kaye, J. P. 2021. \Mitigating nitrogen pollution with undersown legume-grass cover crop mixtures in winter cereals" in press at Journal of Environmental Quality doi:10.1002/jeq2.20193 2. Isbell, S. A., Bradley, B. A., Morris, A. H., Wallace, J. M., Kaye, J. P. 2021. \Nitrogen dynamics in grain cropping systems integrating multiple ecologically- based management strategies" Ecosphere doi:10.1002/ecs2.3380 3. Meyer, K. M., Morris, A. H., Webster, K., Klein, A., Kroegerv, M. E., Meredith, L. K., Brændholt, A., Nakamurat, F., Venturinit, A., Fonseca de Souzat, L., Shek, K. L., Danielson, R., van Haren, J., Barbosa de Camargot, P., Tsait, S. M., Dini- Andreote, F., N¨usslein, K., Saleska, S. R., Rodrigues, J. L. M., Bohannan, B. J. M. 2020. \Belowground changes to community structure alter methane-cycling dynamics in Amazonia" Environment International doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.106131 4. Meyer, K. M., Hopple, A. M., Klein, A., Morris, A.H., Bridgham, S. D., Bohannan, B. J. M. 2020. \Community structure{ecosystem function relation- ships in the Congo Basin methane cycle depend on the physiological scale of function." Molecular Ecology. -

Abraham J.B. Cable [email protected]

Abraham J.B. Cable [email protected] TEACHING EXPERIENCE University of California, Hastings College of the Law 2011 through present Professor University of California, Berkeley School of Law Spring 2014; Summer 2016 Visiting Professor Willamette University College of Law Spring 2011 Adjunct Professor University of Oregon School of Law 2008 through 2010 Adjunct Professor EXPERTISE Business Associations, Legal Ethics, Mergers & Acquisitions, Securities Regulation, Venture Capital PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Miller Nash LLP Partner 2008 through 2011 Associate 2000 through 2007 EDUCATION Harvard Law School, J.D., 2000 Cum laude Harvard Law Review, Editor and Articles Committee University of Puget Sound, B.A., in History with honors, 1997 PUBLICATIONS "Fool’s Gold? Equity Compensation & the Mature Startup," 11 Virginia Law & Business Review (forthcoming 2017) "Institutionalized Disruption: The Rise of the Reformer Startup," 12 Hastings Business Law Journal 1 (2015) "Opportunity-Cost Conflicts in Corporate Law," 66 Case Western Reserve Law Review 51 (2015) "Mad Money: Rethinking Private Placements," 71 Washington & Lee Law Review 2253 (2014) "Startup Lawyers at the Outskirts," 50 Willamette Law Review 163 (2014) "Incubator Cities: Tomorrow’s Economy, Yesterday’s Start-Ups," 2 Michigan Journal of Private Equity & Venture Capital Law 195 (2013) "Fending for Themselves: Why Securities Regulations Should Encourage Angel Groups," 13 University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law 107 (2010) Recent Cases, "Tenth Circuit Holds That City -

ECAP Best Practices & Resources for High School

EDUCATION AND CAREER ACTION PLAN (ECAP) BEST PRACTICES & RESOURCES Listed below are best practices that may be implemented to strengthen your district’s/school’s ECAP process. Under each practice, you will see components of a quality ECAP process that align to each practice. For the complete list of these key components, please see the Quality ECAP Process document, available here or at the end of this list. The Quality ECAP Process tool is designed to assist your district/school in assessing your level of ECAP implementation as well as identifying inhibiting and promoting factors. Keep in mind, there are numerous resources and examples that can assist your district/school in your ECAP process found on the Arizona Department of Education’s ECAP website as well as Dr. V. Scott Solberg’s ILP How-To Guide. ADVISORY PERIODS Self-Exploration Activities (1) AzCIS – Employability Skills Survey, intoCareers, University of Oregon AzCIS – Learning Styles Survey, intoCareers, University of Oregon O*NET Ability Profiler, O*NET, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration O*NET Interest Profiler, O*NET, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (also in AzCIS) Skill and Ability Videos, CareerOneStop, sponsored by the United States Department of Labor Six Core Work Values, O*NET, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration Arizona Career Information System (AzCIS), intoCareers, University of Oregon Going to College: My Place, Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Workplace Supports and Job Retention, Virginia Commonwealth University Career Exploration Activities (2) Interest Assessment, CareerOneStop, sponsored by the U.S. -

News04-1Vpyy0s.Pdf

Chemistry News COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES · DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY · 2004 7 Chemistry Demonstrations INSIDE Randy Sullivan makes the SPECIAL EDITION General and Introductory concepts come alive in the Chemistry—Gateways to classroom Innovations in First-Year the Sciences 8 The Teaching Effective- ness Program Where 3 Message from the faculty learn new skills Chemistry Education Department Head for teaching general and 4 Charles J. and M. Monte- Introductory Chemistry Editor’s Preface ith Jacobs Instructional 8 Chemistry Department emember your days in General Chemistry? You would Endowment Breaks New Reaches Out to Com- Rstill recognize the classrooms, but much else has Ground in Support of munity Promoting the Undergraduate Educa- changed. Our lead article describes General Chemistry discipline of chemistry, lecture and laboratory, and the SUPeR Chemistry tutoring tion Charles J. Jacobs, the department, and the ’34, Establishes the First university through con- available for students needing individual help. Following are Undergraduate peer tutor tacts with elementary and short descriptions of some of the other resources available endowment in chemistry middle school students to entering students: Introductory Chemistry, Pathways, the 4 Honors General Chem- 9 Student Affiliates of ACS istry—The Gateway for Chemistry Resource Center, and the Teaching Effective- Sweep National Awards ness Program. Space limitations preclude coverage of many Advanced Students Undergraduates win four 5 Honors General Chemistry awards and grants additional resources provided by the university, such as Laboratory—Something counseling and special services for students with disabilities, Regular Features and News Special for the Advanced all of which contribute to making the freshman experience a Student Small groups 10 Donor’s Honor Roll positive one. -

A HISTORY of ANTI-WARACTIVITY at the UNIVERSITY of OREGON

A HISTORY Of ANTI-WAR ACTIVITY AT THE UNIVERSITY Of OREGON 1964-1970 by GARY BARNUM Presented to the Department of History and the Honors College of the University of Oregon in partial fUlfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honors College) June 1977 -------------------- f "What makes Washington policy makers think the American people are going to support for long a war effort that is merely an upholding of a mistake? How many Americans are willing to spend and die for that?" Senator Wayne Morse From the floor of the U.S. Senate June 2, 1964 " •••administrative policy will not be made in the streets." Vice President Spiro Agnew In response to the first Moratorium October 16, 1969 ---------------------, TABLE OF CONTENTS "Prefacell Ulntroduction" Chapter I "1964-1966" page 1-8 Chapter II "1966-Summer 1968" page 9-22 Chapter III "Summer 1968-1970" page 23-35 Chapter IV "Winter and Spring 1970" page 36-44 Chapter V "After Kent State" page 45-47 Chapter VI IlConclusion" page 48-50 flAppendixlt page IU-A40 1t8ibliography" Preface The University is quiet this year. The stillness has been broken by small outcries against tuition increases and apartheid, or for child care, but these seem to be ghostly remnants of a bygone era. ROTC men are once more found in uniform on campus, the Greek organizations have revived and dormitories filled again, and education has once more ap peared 'relevant.' In this quiescent atmosphere one is apt to forget or, worse still, log into anecdotal memory the not so distant past, when the radicalized faculty and students of the 1960s dominated campus life.