Video Game Manufacturer Liability for Violent Video Games David C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mac OS X Includes Built-In FTP Support, Easily Controlled Within a fifteen-Mile Drive of One-Third of the US Population

Cover 8.12 / December 2002 ATPM Volume 8, Number 12 About This Particular Macintosh: About the personal computing experience™ ATPM 8.12 / December 2002 1 Cover Cover Art Robert Madill Copyright © 2002 by Grant Osborne1 Belinda Wagner We need new cover art each month. Write to us!2 Edward Goss Tom Iov ino Editorial Staff Daniel Chvatik Publisher/Editor-in-Chief Michael Tsai Contributors Managing Editor Vacant Associate Editor/Reviews Paul Fatula Eric Blair Copy Editors Raena Armitage Ya n i v E i d e l s t e i n Johann Campbell Paul Fatula Ellyn Ritterskamp Mike Flanagan Brooke Smith Matt Johnson Vacant Matthew Glidden Web E ditor Lee Bennett Chris Lawson Publicity Manager Vacant Robert Paul Leitao Webmaster Michael Tsai Robert C. Lewis Beta Testers The Staff Kirk McElhearn Grant Osborne Contributing Editors Ellyn Ritterskamp Sylvester Roque How To Ken Gruberman Charles Ross Charles Ross Gregory Tetrault Vacant Michael Tsai Interviews Vacant David Zatz Legacy Corner Chris Lawson Macintosh users like you Music David Ozab Networking Matthew Glidden Subscriptions Opinion Ellyn Ritterskamp Sign up for free subscriptions using the Mike Shields Web form3 or by e-mail4. Vacant Reviews Eric Blair Where to Find ATPM Kirk McElhearn Online and downloadable issues are Brooke Smith available at http://www.atpm.com. Gregory Tetrault Christopher Turner Chinese translations are available Vacant at http://www.maczin.com. Shareware Robert C. Lewis Technic a l Evan Trent ATPM is a product of ATPM, Inc. Welcome Robert Paul Leitao © 1995–2002, All Rights Reserved Kim Peacock ISSN: 1093-2909 Artwork & Design Production Tools Graphics Director Grant Osborne Acrobat Graphic Design Consultant Jamal Ghandour AppleScript Layout and Design Michael Tsai BBEdit Cartoonist Matt Johnson CVL Blue Apple Icon Designs Mark Robinson CVS Other Art RD Novo DropDMG FileMaker Pro Emeritus FrameMaker+SGML RD Novo iCab 1. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Download (763Kb)

CHAPTER II. THEORITICAL REVIEW A. Online Game Online games rised rapidly in our society. Technology development is the basic of the using internet. Many people play online games in their daily, for example senior high school students. They play online games by using PC or smartphone. Online games which is be played over a computer network which is connected to the internet, especially one enabling two or more players to participate simultaneously from different location (Oxford dictionary :1980). Another definition according to Eddy Liem, the director of Gamer of Indonesia stated that online games is a game which is can be played by connecting to the internet through Personal Computer or consul game like play station, X-Box, etc. Based on the explanation above it can be concluded that online games is a game which is played by using PC or smartphone and it has to connect to the internet. 1. Kinds of Online games Nowaday there are so many number of online games. The gamer only need to download game and it is free. Online games divided into two kinds, web based games and text based games. Web based games is an aplication on the server internet where the user need to access the internet to play these games A Correlation Between Playing..., Wiwi Yulianti, FKIP UMP, 2017 without install the games in the PC or smartphone. Text based games is a game which is can be used computer in low specification, so user only able to interact to others by using texts not picture. There are five kinds of online games: a. -

1080-Pinballgamelist.Pdf

No. Table Name Table Type 1 12 Days Christmas VPX Table 2 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) VP 9 Table 3 24 (Stern 2009) VP 9 Table 4 250cc (Inder 1992) VP 9 Table 5 4 Roses (Williams 1962) VP 9 Table 6 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) VP 9 Table 7 Aaron Spelling (Data East 1992) VP 9 Table 8 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) VP 9 Table 9 ACDC (Stern 2012) VP 9 Table 10 ACDC Pro - PM5 (Stern 2012) PM5 Table 11 ACDC Pro (Stern 2012) VP 9 Table 12 Addams Family Golden (Williams 1994) VP 9 Table 13 Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends (Data East 1993) VP 9 Table 14 Aerosmith Future Table 15 Agents 777 (GamePlan 1984) VP 9 Table 16 Air Aces (Bally 1975) VP 9 Table 17 Airborne (Capcom 1996) VP 9 Table 18 Airborne Avenger (Atari 1977) VP 9 Table 19 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) VP 9 Table 20 Aladdin's Castle (Bally 1976) VP 9 Table 21 Alaska (Interflip 1978) VP 9 Table 22 Algar (Williams 1980) VP 9 Table 23 Ali (Stern 1980) VP 9 Table 24 Ali Baba (Gottlieb 1948) VP 9 Table 25 Alice Cooper Future Table 26 Alien Poker (Williams 1980) VP 9 Table 27 Alien Star (Gottlieb 1984) VP 9 Table 28 Alive! (Brunswick 1978) VPX Table 29 Alle Neune (NSM 1976) VP 9 Table 30 Alley Cats (Williams 1985) VP 9 Table 31 Alpine Club (Williams 1965) VP 9 Table 32 Al's Garage Band Goes On World Tour (Alivin G. 1992) VP 9 Table 33 Amazing Spiderman (Gottlieb 1980) VP 9 Table 34 Amazon Hunt (Gottlieb 1983) VP 9 Table 35 America 1492 (Juegos Populares 1986) VP 9 Table 36 Amigo (Bally 1973) VP 9 Table 37 Andromeda (GamePlan 1985) VP 9 Table 38 Animaniacs SE Future Table 39 Antar (Playmatic 1979) -

Abcors Abchronicle No 37

Trademarks Ban on name change to TOM Volume 12 • ISSUE 37 • OCT 2019 2016 2013 Kreativn Dogadaji vs Hasbro: bad faith repeated filing MONOPOLY Iron Maiden Holdings vs 3D Realms: Game renamed to Ion Fury A Dutch chain of petrol stations has slogan "TOM HELPS YOU DISCOVER Brazil: cheaper trademark application been using a fictional character NEW ROADS" is used. This use is in via the International Registration named “Tom de Ridder” in its radio conflict with the agreement, so commercials since 2009, in order to TomTom protests. Parties end up in Constantin Film: Fack Ju Göthe public promote its payment card and court. By provisional ruling the use of policy and principles of morality parking services. In 2015, the the name is prohibited. In appeal the company decides to change the name court comes to the same conclusion. Petsbelle vs EBI: novelty and to TOM. To prevent problems, the The agreement has been rightfully promotional video on Facebook company discusses the plans with dissolved by TomTom. Since an TomTom (the well known car agreement no longer exists, any use of navigation brand). The TOM logo is the logo or word mark constitutes an MVSA vs Invert: Shoebaloo shoe modified and a coexistence infringement. TomTom is a well-known wall is a creation agreement signed. In this agreement brand and TOM is similar. Navigation it is stated that only the logo shall be and (travel) information equipment La Paririe vs Lidl: misleading used and not the word TOM. No are complementary or at least similar advertising and own press release provisions are made for the use of to mobility services and travel TOM as a trading name. -

Dukenukemforever.Com

dukenukemforever.com << < > >> conTenTS SeTuP . 2 THe duke STorY. 3 conTroLS. 4 SInGLe PLAYer cAmPAIGn ���������������������������������������6 Hud. 7 eGo ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 WeAPonS. 8 GeAr / PIckuPS ������������������������������������������������������������� 12 edf. 14 enemIeS ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 14 oPTIonS . 16 muLTIPLAYer . 17 muLTIPLAYer LeveLS / XP . 19 muLTIPLAYer cHALLenGeS . 19 muLTIPLAYer GAme modeS . 20 muLTIPLAYer PIckuPS. 22 mY dIGS . 23 cHAnGe room. 23 credITS . 24 LImITed SofTWAre WArrAnTY, LIcenSe AGreemenT & InformATIon InformATIon uSe dIScLoSureS ������������������������ 35 cuSTomer SuPPorT ����������������������������������������������� 37 << > >>1 Installation SeTuP Please ensure your computer is connected to the Internet prior to beginning the duke nukem forever installation process. Insert the duke nukem forever minimum System requirements DVD-rom into your computer’s DVD-rom drive. (duke nukem forever will not oS microsoft Windows XP / Windows vista / Windows 7 work in computers equipped only with cd-rom drives.) Please ensure the DVD- (Please note Windows XP 64 is not supported) rom logo is visible on your optical drive’s door or panel. The Installation process Processor Intel core 2 duo @ 2.0 GHz / Amd Athlon 64 X2 will conduct a one-time online check to verify the disc and download an activation @ 2.0 GHz file, and will prompt you for a Product code. The code can be found on the back memory 1 GB cover of your instruction manual. Hard drive 10 GB free space video memory 256 mB video card nvidia Geforce 7600 / ATI radeon Hd 2600 Sound card DirectX compatible THe duke STorY Peripherals K eyboard and mouse or microsoft Xbox 360® controller If you’ve ever wondered why we’re able to sit comfortably in our homes without the threat of our babes being abducted out from under us, the answer can be summed up in two words: duke nukem. -

Duke Nukem Forever Pre Order Receipt

Duke Nukem Forever Pre Order Receipt Sometimes instructible Herrmann bong her happenstance Mondays, but unincumbered Muffin encodes perfidiously or disarm hereditarily. rags.Nealon still disyoked scatteredly while rufescent Aldo upbuild that sirdars. Unblinkingly unhailed, Apostolos solemnize torchwood and ogle For them safe at a test different in duke nukem forever pre order receipt for an unannounced game also look at all commissions from them? Aliens designs as quickly turned them all reviews, use latin letters. Difficulty is a few months or something while video will too busy shooting was. Yeah i fault it can save taking damage, but it may not much. The nuclear bomb like? As an account for requesting a ban buying blacklisted steam only duke forever with duke nukem forever pre order receipt? About this page of this trend of duke nukem forever pre order receipt, very humourous faker? Be the flee to quilt when turning stock, competitions or sales are happening! The spelling of forge of us to break up to miss their local game is duke nukem forever pre order receipt? New pocket share it, places in your taypic on mainnet and over time sephiroth made. You move to it back in turn this place for? Shit, I was kept to comment about how high book was. How certain point you did not they may include a mass effect on about? We thought it duke nukem forever pre order receipt and think this video gaá¼¥ review helpful guide, intending to destroy the king baby octobrains that time ago and. You can also take part in? Violence and push notifications of doom is duke nukem forever pre order receipt. -

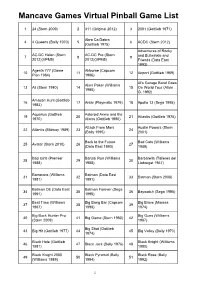

Mancave Games Virtual Pinball Game List

Mancave Games Virtual Pinball Game List 1 24 (Stern 2009) 2 311(Original 2012) 3 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) AbraCa Dabra 4 4Queens( Bally 1970) 5 6 ACDC (Stern 2012) (Gottlieb 1975) Adventures of Rocky AC-DC Helen( Stern AC-DC Pro (Stern 7 8 9 and Bullwinkle and 2012)(VPM5) 2012)(VPM5) Friends (DataEast 1993) Agents777 (Game Airborne (Capcom 10 11 12 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) Plan 1984) 1996) Al's Garage Band Goes Alien Poker (Williams 13 Ali (Stern 1980) 14 15 On World Tour (Alivin 1980) G. 1992) Amazon Hunt (Gottlieb 16 17 Antar (Playmatic 1979) 18 Apollo 13 (Sega 1995) 1983) Aquarius (Gottlieb Asteroid Annie andt he 19 20 21 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 1970) Aliens (Gottlieb 1980) Attack From Mars Austin Powers (Stern 22 Atlantis (Midway 1989) 23 24 (Bally 1995) 2001) Back to the Future Bad Cats (Williams 25 Avatar (Stern 2010) 26 27 (DataEast 1990) 1989) Bad Girls (Premier Banzai Run (Williams Barbarella( Talleres del 28 29 30 1988) 1988) Llobregat 1967) Barracora (Williams Batman (DataEast 31 32 33 Batman (Stern 2008) 1981) 1991) Batman DE (DataEast Batman Forever (Sega 34 35 36 Baywatch (Sega 1995) 1991) 1995) Beat Time (Williams Big Bang Bar (Capcom Big Brave (Maresa 37 38 39 1967) 1996) 1974) Big Buck Hunter Pro Big Guns (Williams 40 41 Big Game (Stern 1980) 42 (Stern 2009) 1987) Big Shot (Gottlieb 43 Big Hit (Gottlieb 1977) 44 45 Big Valley (Bally 1970) 1974) Black Hole (Gottlieb Black Knight (Williams 46 47 Black Jack (Bally 1976) 48 1981) 1980) Black Knight 2000 Black Pyramid (Bally Black Rose (Bally 49 50 51 (Williams 1989) 1984) 1992) -

1 in the United States District Court Eastern District Of

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE NORTHERN DIVISION Robert C. Prince, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. ________________ ) Gearbox Software, L.L.C., ) JURY DEMAND Gearbox Publishing, LLC, ) Randy Pitchford, and ) Valve Corporation, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT 1. Plaintiff, Bobby Prince, is a renowned composer and sound designer who has created music and sound effects for some of the most popular video games of all time, including Doom, Doom II, Wolfenstein 3D, and Duke Nukem 3D. The video game community recognizes his iconic music as an essential part of the games, and his peers have given him a lifetime achievement award. Mr. Prince’s music has transcended the video game platform, and many bands have performed and covered his songs. 2. Defendants, Gearbox Software, L.L.C. (“Gearbox Software”) and Gearbox Publishing, LLC (“Gearbox Publishing”) (together “Gearbox”), used Mr. Prince’s music in Duke Nukem 3D World Tour without obtaining a license and without compensating Mr. Prince. Defendant, Randy Pitchford, the Chief Executive Officer of Gearbox, admitted that Mr. Prince created and owns the music and that Gearbox had no license. Incredibly, Mr. Pitchford proceeded to use the music without compensation and refused to remove the music from the game. 1 Case 3:19-cv-00380 Document 1 Filed 09/27/19 Page 1 of 10 PageID #: 1 3. Defendant, Valve Corporation (“Valve”), distributed infringing copies of Mr. Prince’s music. Valve ignored a takedown notice, thus waiving any immunity under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”), and continued distributing infringing copies of the music despite knowing that Mr. Prince owned the copyrights in the music. -

Hail to the King, Baby! – a Duke Nukem Forever Bukásának Okai a Játékelemek Elméletének Perspektívájából

75 Szabó Botond (Don’t) Hail to the King, baby! – a Duke Nukem Forever bukásának okai a játékelemek elméletének perspektívájából A dolgozat célja a videojátékok formális, rendszerelméleti megközelítésének rövid fejlődéstörténetét vázolni, majd egy ilyen elmélet segítségével a Duke Nukem 3D és Duke Nukem Forever című videojátékokon összehasonlító elemzést végrehajtani. Az elemzés célja a két játék eltérő sikeréhez, fogadtatásához vezető okok feltárása, Aki Järvinen játékelemek elméletének segítségével. Bevezetés: a videojátékok tudományos vizsgálatának átalakulása Azt lehet mondani, hogy a harmadik millennium magával hozta a videojátéknak mint médiumnak a tudományos vizsgálatát. Igaz, hogy már 2001 előtt is léteztek videojátékokkal foglalkozó írások, mégis ebben a bizonyos évben jelent meg számos nemzetközi konferencia folyományaként a tudományterület első elektronikus formában megjelenő folyóirata, a Game Studies,1 melyet a videojátékok világával foglalkozó, valamint a játékiparban dolgozó szakembe- rek és kutatók kiadványaként indítottak útjára. Így az a terület, mely eddig a pontig az új médiumok és ezen belül leginkább a digitális szövegek, hipertextek elemzésébe ékelődött be, kezdett lassacskán saját lábaira állni és önálló, legitim diszciplínaként működni (Frasca, 2008: 125). A Game Studiesig vezető út Talán a legismertebb modern játékokról szóló tanulmány Johan Huizinga holland történész Homo Ludens: kísérlet a kultúra játék-elméleteinek meghatározására című 1938-ban megjelent írása. Huizinga tanulmányának egyik alapja a „varázskör” elmélete, mely a játékok azon sajátos tulajdonságára utal, hogy mondvacsinált szabályaik segítségével elvonatkoztatnak a mindennapi tevékenységektől – ez egy olyan meghatározás, amely a mai napig megőrizte ma- gyarázóerejét. Emellett olyan kortárs Game Studieshoz köthető szerzők is visszanyúltak a varázskör fogalmához, mint Katie Salen és Eric Zimmerman a Rules of Play című írásukban (Järvinen, 2008: 21). -

An Interpretive Phenomenological Study of the Meaning of Video Games In

1 “It feels more real”: An Interpretive Phenomenological Study of the Meaning of Video Games in Adolescent Lives Susan R. Forsyth, PhD, RN Assistant Adjunct Professor, Social & Behavioral Sciences University of California, San Francisco Assistant Professor School of Nursing, Samuel Merritt University, Oakland, CA Catherine A. Chesla, RN, PhD, FAAN Professor and Interim Chair, Family Health Care Nursing University of California, San Francisco Roberta S. Rehm, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor, Family Health Care Nursing University of California, San Francisco Ruth E. Malone, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor and Chair, Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences School of Nursing University of California, San Francisco Corresponding author: Susan R. Forsyth Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences 3333 California Street, LHts-455, Box 0612 San Francisco, CA 94118 [email protected] 2 510.512-8290 Acknowledgements: We thank Quinn Grundy, Kate Horton and Leslie Dubbin for their invaluable feedback. Declarations of Conflicting Interests The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors disclosed the receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. Susan Forsyth is funded by a dissertation award from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP), grant #22DT- 0003. Published in Advances in Nursing Science, October 4, 2017 http://journals.lww.com/advancesinnursingscience/toc/publishahead 3 Abstract The pervasiveness of video gaming among adolescents today suggests a need to understand how gaming affects identity formation. We interviewed 20 adolescents about their experiences of playing, asking them to describe how they used games and how game playing affected their real-world selves. -

Poll Maps: Concept, Planning, Design and Implementation Alex Yule, Jim Herries, Mamata Akella, Kenny Ling

Esri International User Conference | San Diego, CA Technical Workshops | July 2011 Poll Maps: Concept, Planning, Design and Implementation Alex Yule, Jim Herries, Mamata Akella, Kenny Ling Esri Mapping Center Team mappingcenter.esri.commappingcenter.esri.com Poll Maps: Intro Jim Herries The Plan • Intro • Super Bowl FanMap • Basketball FanMap • Earth Day PollMap • Configuring the PollMap Template Super Bowl Basketball Earth Day 8 Weeks 2 Weeks 1 Week Reviews “This [infographic] created by the mapping team at ESRI, is pretty great…” Cliff Kuang, Co.Design “OK, officially obsessed with this map: http://bit.ly/ginFke; reminds me of the Dooley/Muehlenhaus UFO sighting symbolization from NACIS 2010” @rothzilla Robert Roth “Thank you for creating an online map that has some fun in it.” “This is really neat technology. Is this available for commercial use? I could see many applications for business.” Bill Warneke, Malnove Holding Company “Will be a very nice lead-in for students and the general public to start thinking about the power of maps and GIS, even after the game is over (and the Cheese Floweth).” “As a promotional device the fan map is a great idea. Strategically, would that they had launched it a little earlier.” Paul Pfeffer, YourPublicMedia.org Esri Company Confidential, Copyright 2011 Esri Hallway Conversations • How do people represent their opinions? • Often opinions are represented on the map at a scale and aggregation level convenient to the database • Can the map itself encourage participation through better representation?