08-1521 Mcdonald V. Chicago (06/28/2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Thinking Clearly

For Sabine The Art of Thinking Clearly Rolf Dobelli www.sceptrebooks.co.uk First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Sceptre An imprint of Hodder & Stoughton An Hachette UK company 1 Copyright © Rolf Dobelli 2013 The right of Rolf Dobelli to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. eBook ISBN 978 1 444 75955 6 Hardback ISBN 978 1 444 75954 9 Hodder & Stoughton Ltd 338 Euston Road London NW1 3BH www.sceptrebooks.co.uk CONTENTS Introduction 1 WHY YOU SHOULD VISIT CEMETERIES: Survivorship Bias 2 DOES HARVARD MAKE YOU SMARTER?: Swimmer’s Body Illusion 3 WHY YOU SEE SHAPES IN THE CLOUDS: Clustering Illusion 4 IF 50 MILLION PEOPLE SAY SOMETHING FOOLISH, IT IS STILL FOOLISH: Social Proof 5 WHY YOU SHOULD FORGET THE PAST: Sunk Cost Fallacy 6 DON’T ACCEPT FREE DRINKS: Reciprocity 7 BEWARE THE ‘SPECIAL CASE’: Confirmation Bias (Part 1) 8 MURDER YOUR DARLINGS: Confirmation Bias (Part 2) 9 DON’T BOW TO AUTHORITY: Authority Bias 10 LEAVE YOUR SUPERMODEL FRIENDS AT HOME: Contrast Effect 11 WHY WE PREFER A WRONG MAP TO NO -

Proceedings of the Democratic State Convention

ij >vl-C>6<£ Jl PROCEEDINGS. OT TH1 DEMOCRATIC STATE CONVENTION, WHICH ASSERaOBOLESD' AT LEWISTOWN, ©N Wednesday, *Way ®tk, IS 85* HARRISBURG: PRINTED BY CRABB dr BARRETT, £@35. A The delegates elected from the different counties of the common¬ wealth assembled at Levvistown on Wednesday, the 6th of May, 1835. On motion, Col. JOHN DICKEY, of Beaver, was called to the chair, and Andrew G. Miller, of Adams, H. G. Rogers, of Alleg¬ heny, and Henry Shoemaker, of the city of Philadelphia, Were ap¬ pointed Secretaries, for the purpose of organizing the convention. Pursuant to a resolution, the counties were called in alphabetical order, and the following named delegates appeared, presented their Credentials and took their seats: Adams.—Zephaniah Herbert, A. G. Miller, Thos. McCreery. Allegheny.—/Absalom Morris, Win. Caven, Patrick Mulvany, IX. G. Rogers, Linton Rogers. Armstrong.—Robert Robinson. Senatorial—David Reynolds. Beaver.—Jcfhn Dickey, John M. Lukens. Bedford.— James Patton. Berks.—Thomas Morris, Mark Darrah, Jacob Geehr, William Fisher, Le¬ wis W. Richards. Bradford 8f Tioga—Samuel Weeks, Dr. D. L. Scott. Senatorial—Dr. Seth Salisbury. Bucks.—Gen. S. A. Smith, David Todd, Hervey Matthias, John Comfort, Jr. Butler.—James Potts, jr. Senatorial—Samttel A. Gilmore. Centre fy Clearheld.—Dr. Constans Curten, Col. George Hubler. Senatorial —Thomas Hemphill. Chester.—John Morgan, Joseph Maekleduff, David Furey, Robert Cowan, Joseph Hemphill, ji. Columbia—John F. Derr, Col. Frederick Shirtz. Crawford.—'William McLaughlin. Senatorial—Samuel W. Magill. Cumberland.—Charles B. Penrose, Hugh Wallace. Senatorial—George Beaver. Dauphin.—John C. Bucher, Jacob Seal. Delaware.—Wm. B. Sill, A. T. Dick. Brie.—Henry Colt. -

The Visser Chronicles

1 Animorphs Chronicles 3 Visser K.A. Applegate *Converted to EBook by asmodeus *edited by Dace k 2 Prologue “Honey?” No answer. My husband was watching a game on television. He was preoccupied. “Honey?” I repeated, adding more urgency to my tone of voice. He looked over. Smiled sheepishly. “What’s up?” “Marco’s fever is down. I think he’s basically over this thing. He’s asleep. Anyway, I was thinking of getting some fresh air.” He muted the television. “Good idea. It’s tough when they’re sick, huh? Kids. He’s okay, though, huh?” “It’s just a virus.” “Yeah, well, take some time, you’ve been carrying the load. And if you’re going to the store- “ “Actually, I think I’ll go down to the marina.” He laughed and shook his head. “Ever since you bought that boat… I think Marco has some competition as the favorite child in this household.” He frowned. “You’re not taking it out, are you? Looks kind of gloomy out.” I made a smile. “Just want to make sure it’s well secured, check the ropes and all.” He was back with the game. He winced at some error made by his preferred team. “Uh-huh. Okay.” I stepped back, turned, and walked down the hall. The door to Marco’s room was ajar. I paused to look inside. I almost couldn’t do otherwise because the other voice in my head, the beaten-down, repressed human voice, was alive and screaming and screaming at me, begging me, pleading <No! No! No!> Marco was still asleep. -

A Novel Decision Making Model of the Globalizing Consumer Behavior

A NOVEL DECISION - MAKING MODEL OF THE GLOBALIZING CONSUMER BEHAVIOR: EVIDENCE FROM CHINESE MIDDLE - CLASS CONSUMERS WHO PURCHASE LUXURY GOODS FROM OVERSEAS MARKETS Presented by Yang Liu Southern New Hampshire University 2500 North River Road, Manchester, New Hampshire 03106, USA Dissertation Committee: Dr. Aysun Ficici, Chair Professor of International Business and Strategy Dr. Massood Samii Professor of International Business Dr. Tej Dhakar Professor of Management Science Dr. Ling Ling Wang Assistant Professor of International Business Worcester State University 1 Dedication I would like to dedicate my dissertation to my grandparents who raised me up and taught me perseverance. I would also like to dedicate my dissertation to my parents who encourage me to pursue this path, always support me, and teach me to be principled, ethical and intellectual. Finally, I would like to dedicate my dissertation to my friend, Wei Liu who through his giftedness accompanied me in the hard times during this journey. 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my Dissertation Committee Chair, Professor Aysun Ficici who has supported me from the very beginning of my doctoral journey. As my Dissertation Committee Chair, she guided me structurally both qualitatively and quantitatively through her deep knowledge in variety of subject areas, who also stayed with me after hours to work on my dissertation with me. She taught me how to be a good researcher, a good writer, and an academician. I would like to thank Professor Tej Dhakar for his valuable assistance in providing me feedback in my quantitative research. I would like to thank Professor Massood Samii for guiding me in the process and sharing his deep knowledge in the field of strategy. -

A Novel Framework for Threat Analysis of Machine Learning-Based Smart Healthcare Systems

A Novel Framework for Threat Analysis of Machine Learning-based Smart Healthcare Systems Nur Imtiazul Haque∗, Mohammad Ashiqur Rahman∗, Md Hasan Shahriar∗ Alvi Ataur Khalil∗ and Selcuk Uluagacy ∗Analytics for Cyber Defense (ACyD) Lab, yCyber-Physical Systems Security Lab Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Florida International University, Miami, USA f nhaqu004, marahman, mshah068, akhal042, suluagacg@fiu.edu Abstract—Smart healthcare systems (SHSs) are providing fast and triggers implantable medical devices (IMDs) for real-time and efficient disease treatment leveraging wireless body sensor medication and treatment. Currently, healthcare facilities are networks (WBSNs) and implantable medical devices (IMDs)- more efficient, accessible, and personalized as the SHS is based internet of medical things (IoMT). In addition, IoMT-based SHSs are enabling automated medication, allowing communication ameliorating disease diagnostic tools, treatment for patients, among myriad healthcare sensor devices. However, adversaries and healthcare devices, thus improving the quality of lives [6]. can launch various attacks on the communication network and However, an SHS requires processing a lot of historical data to the hardware/firmware to introduce false data or cause data identify anomalous sensor measurements. The data related to unavailability to the automatic medication system endangering healthcare and medication are affluent. They can be utilized to the patient’s life. In this paper, we propose SHChecker, a novel threat analysis framework -

Order Shade Tree at Half-Pricc Red Men Elect Wilson

It Pays To Advertise In The Times I ANTI THE NEPTUNE TIMES Vo). XC, No. 15 OCEAN GROVE TIMES. TOWNSHIP OP NEPTUNE, NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, APRIL 9, 1965 SEVEN CENTS Order Shade Tree Schedule Shots Attend Laymen’s Convocation Apr. 3-4 Over $187,000 In Twp. Adult School Nine Concerts In At Half-Pricc For Smallpox Mar. Construction Plans New Term Summer Season Township Makes Offer NEPTUNE — The . Neptune Building Inspector Re Plans Judo, Yogi and Special Events Commit To First 100 Residents; Township Board of Education ports To Committee; Hear Guitar For Sept, Ses tee Arranges Programs lias adopted the following sche* sions; Preparing History In Grove’s Auditorium County Continues Planting dule of vaccinations against ings Apr. 20 on Transfer smallpox. These innoculatlons NEPTUNE TWP.—A total cf NEPTUNE—The regular month OCEAN GROVE—A series , NEPTUNE' TWP.—'The are required every seven years. ly meeting of the Neptune Adiilt township’s Shade' Tree Com 40 permits, with an estimated con of outstanding concerts has mission is offering 100 trees to Thursday,, April 22, Ridge struction value of $187,449, were School Steering Committee was oeen arranged for the Ocean Avenue School; Friday, April issued in the township during held on Tuesday, April 6, at 8 p.m. Grove Auditorium this com property owners on a “first a t Neptune High School . come, first served” basis, at . 23, Bradley Park School; Mon March, Building Inspector William ing season, it was announced half price of $10 each. The day, April 26, Whitesville If. Guy, Jr., reported to the mu Plans were formulated in regard this week by the Rev. -

Strategy Formation As Solving a Complex and Novel Problem

Strategy Formation as Solving a Complex and Novel Problem Timothy E. Ott Kenan-Flagler Business School University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4200 Suite, McColl Building, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, U.S.A. Tel. (732) 778 - 6692 Email: [email protected] Ron Tidhar Department of Management Science & Engineering Stanford University Huang Engineering Center 475 Via Ortega Road Stanford, CA 94305 Email: [email protected] Working Paper – 04/10/2018 ABSTRACT In this paper, we seek to better understand how executives can intelligently combine modular and integrated problem solving processes to form the best possible strategy in entrepreneurial environments. To do so, we compare the efficacy of strategies formed via different processes under various market conditions, exploring the sources of significant performance differences. We address this question using NK simulation methods. We show that the ‘decision weaving’ strategy formation process leads to more effective strategies than either local or ‘chunky search’ processes across a variety of problem specifications. We also offer insight into two key concepts of the decision weaving framework; stepping stones and learning plateaus, which allow executives to balance the tradeoff between quality and the speed of the strategy formation process. This provides practical points for executives forming strategy to overcome their own bounded rationality and contributes to literature on strategy processes and complex problem solving within organizations. Keywords: Strategy formation, problem solving, strategic decision making, behavioral theory, simulation 1 Introduction In 2007, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia were struggling to pay rent in San Francisco so they rented out their apartment to three conference attendees to help make ends meet (Tame, 2011). -

Learning in Dynamic Decision Tasks: Computational Model and Empirical Evidence

ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR AND HUMAN DECISION PROCESSES Vol. 71, No. 1, July, pp. 1±35, 1997 ARTICLE NO. OB972712 Learning in Dynamic Decision Tasks: Computational Model and Empirical Evidence Faison P. Gibson University of Michigan Business School, Ann Arbor Mark Fichman Graduate School of Industrial Administration, Carnegie Mellon University and David C. Plaut Departments of Psychology and Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University Dynamic decision tasks include important activities such as stock trading, air traffic control, and managing continuous pro- duction processes. In these tasks, decision makers may use out- come feedback to learn to improve their performance ªon-lineº as they participate in the task. We have developed a computational formulation to model this learning. Our formulation assumes that decision makers acquire two types of knowledge: (1) How their actions affect outcomes; (2) Which actions to take to achieve desired outcomes. Our formulation further assumes that funda- mental aspects of the acquisition of these two types of knowledge can be captured by two parallel distributed processing (neural network) models placed in series. To test our formulation, we instantiate it to learn the Sugar Production Factory (Stanley, Mathews, Buss, & Kotler-Cope, Quart. J. Exp. Psychol., 1989) and then apply its predictions to a human subjects experiment. Our formulation provides a good account of human decision makers' performance during training and two tests of subsequent ability to generalize: (1) answering questions about which actions to take to achieve goals that were not encountered in training; and (2) a new round of performance in the task using one of these new goals. Our formulation provides a less complete account of Address correspondence and reprint requests to Faison P. -

124214015 Full.Pdf

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI DEFENSE MECHANISM ADOPTED BY THE PROTAGONISTS AGAINST THE TERROR OF DEATH IN K.A APPLEGATE’S ANIMORPHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MIKAEL ARI WIBISONO Student Number: 124214015 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI DEFENSE MECHANISM ADOPTED BY THE PROTAGONISTS AGAINST THE TERROR OF DEATH IN K.A APPLEGATE’S ANIMORPHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MIKAEL ARI WIBISONO Student Number: 124214015 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A SarjanaSastra Undergraduate Thesis DEFENSE MECIIAMSM ADOPTED BY TITE AGAINST PROTAGOMSTS THE TERROR OT OTATTT IN K.A APPLEGATE'S AAUMORPHS By Mikael Ari Wibisono Student Number: lz4ll4}ls Defended before the Board of Examiners On August 25,2A16 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Chairperson Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A. Secretary Dra. Sri Mulyani, M.A., ph.D / Member I Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A. Member2 Drs. HirmawanW[ianarkq M.Hum. Member 3 Elisa DwiWardani, S.S., M.Hum Yogyakarta, August 31 z}rc Faculty of Letters fr'.arrr s41 Dharma University s" -_# 1,ffi QG*l(tls srst*\. \ tQrtnR<{l -

The Underground Railroad in Missouri and Kansas

Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater Project The Underground Railroad in Missouri and Kansas The stories of the Underground Railroad appeal to young and old. Tales of courage and conviction have held readers spellbound since 1852, when Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin. We understand from history that the Underground Railroad had to be secret. Who would want to be caught running away, and face the lash or be auctioned away from loved ones as punishment? Who would want to let loose the secret, and be responsible for bungling a runaway’s plea for help and watching him or her be captured? But the penalties for bungling were much steeper for Underground Railroad operators than the mere shame of failure. Operatives, holding to their own code of moral law, risked fearful penalties by defying federal and state laws which favored slaveholders. Nowhere in the United States was the Underground Railroad more dangerous than in western Missouri and eastern Kansas in the late 1850s. Please Note: Regional historians have reviewed the source materials used, the script, and the list of citations for accuracy. The Underground Railroad in Missouri and Kansas is part of the Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project, a partnership between the Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council. FFNHA is a partnership of 41 counties in eastern Kansas and western Missouri dedicated to connecting the stories of settlement, the Border War and the Enduring Struggle for Freedom in this area. KHC is a non-profit organization promoting understanding of the history and ideas that shape our lives and strengthen our sense of community. -

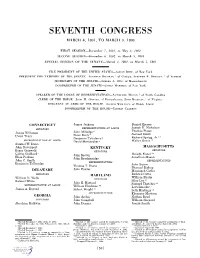

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Inventory of Resources for the WASHINGTON-ROCHAMBEAU

Inventory of Resources for the WASHINGTON-ROCHAMBEAU REVOLUTIONARY ROUTE IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Using the criteria developed in Point 2.3: Goals of the Project, consultant inspected and inventoried on site all resources listed in this report and identified 85 individual resources on 12 separate routes taken by various components and individuals belonging to the two armies in Pennsylvania. These major routes are as follows: Route 1: The Land Route of Generals George Washington and the comte de Rochambeau to Philadelphia in September 1781 Route 2: The Land Route of Continental Army Troops from Trenton, New Jersey to Claymont, Delaware in September 1781 Route 3: The Water Route of Continental Army Troops from Trenton, New Jersey to Christiana, Delaware in September 1781 Route 4: The Land Route of commissaire de guerre de Granville from Boston to Philadelphia in September 1781 Route 5: The Land Route of the French Army Troops from Trenton, New Jersey to Claymont, Delaware in September 1781 Route 6: The Water Route of comte de Rochambeau from Philadelphia to Chester on 5 September 1781, and the continuation of the route on land with Washington to Wilmington Route 7: The Return Marches of the Continental Army in December 1781 Route 8: The Return March of the French Army in September 1782 Route 9: The Philadelphia Conference and the Celebrations for the Birth of the dauphin, 14 to 24 July 1782 Route 10: The March of the Passengers of the l'Aigle and la Gloire from Dover, Delaware to Yorktown Heights, New York in September 1782 Route 11: The March of Lauzun’s Legion from Yorktown Heights, New York to Winter Quarters in Wilmington, Delaware in December 1782 Route 12: Route of Rochambeau to Baltimore via Newton, Hackettstown, Baptistown and Philadelphia in December 1782 Rather than divide the resources by route, they have been listed whenever possible and feasible (without undue impact on the flow of the historical narrative) in the approximate chronological order in which they were visited.