Title: Morris Arboretum Emerald Ash Borer Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cytogenetics of Fraxinus Mandshurica and F. Quadrangulata: Ploidy Determination and Rdna Analysis

Tree Genetics & Genomes (2020) 16:26 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-020-1418-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Cytogenetics of Fraxinus mandshurica and F. quadrangulata: ploidy determination and rDNA analysis Nurul Islam-Faridi1,2 & Mary E. Mason3 & Jennifer L. Koch4 & C. Dana Nelson5,6 Received: 22 July 2019 /Revised: 1 January 2020 /Accepted: 16 January 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Ashes (Fraxinus spp.) are important hardwood tree species in rural, suburban, and urban forests of the eastern USA. Unfortunately, emerald ash borer (EAB, Agrilus planipennis) an invasive insect pest that was accidentally imported from Asia in the late 1980s–early 1990s is destroying them at an alarming rate. All North American ashes are highly susceptible to EAB, although blue ash (F. quadrangulata) may have some inherent attributes that provide it some protection. In contrast Manchurian ash (F. mandshurica) is relatively resistant to EAB having coevolved with the insect pest in its native range in Asia. Given its level of resistance, Manchurian ash has been considered for use in interspecies breeding programs designed to transfer resistance to susceptible North American ash species. One prerequisite for successful interspecies breeding is consistency in chromosome ploidy level and number between the candidate species. In the current study, we cytologically determined that both Manchurian ash and blue ash are diploids (2n) and have the same number of chromosomes (2n =2x = 46). We also characterized these species’ ribosomal gene families (45S and 5S rDNA) using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Both Manchurian and blue ash showed two 45S rDNA and one 5S rDNA sites, but blue ash appears to have an additional site of 45S rDNA. -

Bronze Birch Borer

Pest Profile Photo credit: Tom Murray, BugGuide.net Common Name: Bronze Birch Borer Scientific Name: Agrilus anxius (Gory) Order and Family: Coleoptera; Buprestidae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg Oval and flattened Start out creamy white in color but turn yellow with age Length: 1.5 mm Laid singly or in clusters of 6-7 in branch crevices Width: 1 mm and cracks Larva/Nymph Head is light brown Pale white in color 2-38 mm Flattened appearance Two short, brown pincers Adult Slender, olive-bronze in color with coppery reflections Females: 7.5-11.5 mm Males have a greenish colored head Males: 6.5-10 mm Females have a coppery-bronze colored head Pupa (if Creamy white and then darkens applicable) Pupation occurs within chambers under the bark Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Both larvae and adults have chewing mouthparts. Host plant/s: European white birch, white-barked Himalayan paper birch, gray birch, sweet birch, yellow birch, cottonwood, and sometimes river birch. Description of Damage (larvae and adults): Bronze birch borers prefer trees that are stressed due to drought or defoliation. Larvae feed on the phloem and cambium while creating numerous galleries, which eventually alters nutrient transport and kills off the root system while leading to further necrosis in the major branches and main stem. Adult beetles feed on leaves but do not harm the overall health of the tree. References: Iowa State University. (2003-2016). Species Agrilus anxius - Bronze Birch Borer. Retrieved March 20, 2016, from http://bugguide.net/node/view/56062/tree Katovich, S. -

Bronze Birch Borer

Field Identification Guide Bronze birch borer Photograph: Karl W. Hillig W. Karl Photograph: Funded by the EU’s LIFE programme Bronze birch borer The bronze birch borer (BBB, Agrilus anxius), a beetle belonging to the family Buprestidae, is a serious North American insect pest of birch trees Betula( species). The BBB causes extensive mortality to birch populations and can attack trees with stems greater than 2 cm in diameter and branches of 1 cm in diameter. Damage is caused by larvae feeding on the inner bark and cambium of the tree. Repeated attacks and the excavation of numerous winding galleries by the larvae cause disruption to water and nutrient transportation within the tree, leading to death of tissues above and below ground. In many cases tree mortality is observed within just a few years of the appearance of the first symptoms. Species affected All species of birch are susceptible to this pest. In its natural range of North America, BBB is considered to be a secondary pest of the native birch. In contrast, Asian and European species such as our native silver and downy birch (Betula pendula and B. pubescens) are much more susceptible to this pest. Signs and BBB infestation is usually difficult to detect until the symptoms symptoms become severe because much of the insect’s life cycle is hidden within the tree; eggs are laid in crevices, the larvae feed in the inner bark and pupation occurs in the sapwood. In most cases, the beetles have already become established and have spread to new hosts by the time they are discovered. -

Resistance Mechanisms of Birch to Bronze Birch Borer Vanessa L

Resistance mechanisms of birch to bronze birch borer Vanessa L. Muilenburg1, Pierluigi (Enrico) Bonello2, Daniel A. Herms1 1Department of Entomology, The Ohio State University, Ohio Agricultural Research and Developmental Center (OARDC), Wooster, OH 2Department of Plant Pathology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH contact: [email protected] Abstract Results • Outbreaks of bronze birch borer, Agrilus anxius, a North American wood-boring beetle, have occurred periodically over the last • 14 compounds were analyzed in detail 100 years, causing extensive tree mortality. (Fig. 6) revealing quantitative and (potentially) qualitative differences • Little is known about mechanisms underlying tree resistance to wood-boring insects, but previous studies have suggested that between the two species. secondary metabolites and wound periderm (callus) tissue may play a role. • PC 1 and 2 showed clear variation in • North American birches (Betula spp.) are much more resistant to bronze birch borer than exotic species that lack a phloem chemistry between species coevolutionary history. (Fig 7A). • We compared patterns of constitutive phenolic chemistry and the rate of wound periderm formation in phloem tissues of North American paper birch (B. papyrifera) to exotic European white birch (B. pendula). • Phenolic compounds 1, 10, 11, 12 contributed most variation to PC 1, Fig. 6. Phenolic profiles of paper birch and European white birch phloem. • Six phenolic compounds were in higher concentrations in phloem of paper birch than in European white birch and might be while phenolic compounds 3, 4, 5, 9 involved in resistance. contributed most to PC 2 (Fig 7B). • There were no interspecific differences in rate of wound periderm formation. -

University of Tennessee Instructor Copy

Copy This chapter is an edited version An Overview of the Physical of a manuscript by the same title Environment, Flora, and written by Edward W. Chester. Vegetation of Tennessee In addition to editing, some 2 material has been deleted from and some added to the original Instructormanuscript by the editors of this publication. Portions of the original manuscript were condensed from Guide to the Vascular Plants of Tennessee, compiled and edited by the Tennessee Flora Committee. Copyright © 2015 by The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville. Used by permission granted to Edward W. Chester. See author’s notes for additional Tennessee information. of University Copy AUTHOR'S NOTES A more complete discussion of the topics in this chapter can be found in Chapter 1, “The Physical Environment of Tennessee” (written by Edward W. Chester) and Chapter 3, ”An Overview of the Vegetation of Tennessee” (coauthored by Hal R. DeSelm and William H. Martin) in the Guide to the Vascular Plants of Tennessee referenced at the beginning of this chapter. The contents of the two chapters are based on almost 200 combined years of study by the three authors and the nearly 100 references they cite. The authors are: Instructor Edward W. Chester, Professor Emeritus of Biology and Botany, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, Tenn. Hal R. DeSelm (deceased), Professor Emeritus of Botany and the Graduate Program in Ecology, University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Dr. DeSelm died on July 12, 2011. William H. Martin, Professor Emeritus of Biology and Director of the Division of Natural Areas, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond. He served as Commissioner of Kentucky's Department for Natural Resources from 1992 to 1998. -

Fraxinus Spp. Family: Oleaceae American Ash

Fraxinus spp. Family: Oleaceae American Ash Ash ( Fraxinus sp.) is composed of 40 to 70 species, with 21 in Central and North America and 50 species in Eurasia. All species look alike microscopically. The name fraxinus is the classical Latin name for ash. Fraxinus americana*- American White Ash, Biltmore Ash, Biltmore White Ash, Canadian Ash, Cane Ash, Green Ash, Ground Ash, Mountain Ash, Quebec Ash, Red Ash, Smallseed White Ash, White Ash , White River Ash, White Southern Ash Fraxinus anomala-Dwarf Ash, Singleleaf Ash Fraxinus berlandierana-Berlandier Ash , Mexican Ash Fraxinus caroliniana-Carolina Ash , Florida Ash, Pop Ash, Swamp Ash, Water Ash Fraxinus cuspidata-Flowering Ash, Fragrant Ash Fraxinus dipetala-California Flwoering Ash, California Shrub Ash, Foothill Ash, Flowering Ash, Fringe- flowering Ash, Mountain Ash, Two-petal Ash Fraxinus gooddingii-Goodding Ash Fraxinus greggii-Dogleg Ash, Gregg Ash, Littleleaf Ash Fraxinus latifolia*-Basket Ash, Oregon Ash, Water Ash, White Ash Fraxinus nigra*-American Black Ash, Basket Ash, Black Ash , Brown Ash, Canadian Ash, Hoop Ash, Splinter Ash, Swamp Ash, Water Ash Fraxinus papillosa-Chihuahua Ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica*-Bastard Ash, Black Ash, Blue Ash, Brown Ash, Canadian Ash, Darlington Ash, Gray Ash, Green Ash , Piss Ash, Pumpkin Ash, Red Ash, Rim Ash, River Ash, Soft Ash,Swamp Ash, Water Ash, White Ash Fraxinus profunda*-Pumpkin Ash, Red Ash Fraxinus quadrangulata*-Blue Ash , Virginia Ash Fraxinus texensis-Texas Ash Fraxinus velutina-Arizona Ash, Desert Ash, Leatherleaf Ash, Modesto Ash, Smooth Ash, Toumey Ash, Velvet Ash (* commercial species) Distribution The north temperate regions of the globe. The Tree Ashes are trees or shrubs with large, opposite, pinnately compound leaves, which are shed in the fall. -

Bronze Birch Borer Agrilus Anxious

Bronze birch borer Agrilus anxious Bronze birch borer is a pest of birch trees, especially white barked birches such as Betula papyrifera, B. populifolia, B. pendula and B. maximowicziana. B. papyrifera is much more tolerant of bronze birch borer than B. pendula. Adults are similar in shape Insects overwinter as to twolined chestnut borers larvae in galleries in (photo on page 49) but are the vascular system 8-10 mm long and a dull and resume feeding in metallic bronze in color. spring as the sap rises. 8 10mm Adults emerge over a period of about 6 weeks 8-10mm beginning in late May or early June when pagoda dogwood and ‘Winter King’ hawthorns are in full bloom. Females lay eggs on the bark, and larvae hatch out and begin boring into the bark around the time that European cranberry- bush viburnum or weigela are in bloom. Larvae form winding galleries in the cambium of the tree, girdling branches and disrupting the flow of water and nutrients in the tree. Larvae may take up to two years to complete their development. Lumpy branch is symptom of bronze birch borer. Bronze birch borer - continued Symptoms: Bronze birch borer injury includes dieback that begins in the upper portion of the tree, a lumpy appearance to branches where galleries are present, and D-shaped exit holes in the bark created by emerging adults. Rusty-colored stains may also be visible on bark in the area of entrance or exit holes. Management: Stressed trees are much more prone to injury. Avoid planting birches in hot, dry sites. -

Ash FNR-272-W Daniel L

PURDUE EXTENSION Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series Ash FNR-272-W Daniel L. Cassens, Professor and Extension Wood Products Specialist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 Ash refers to a group of five species ranging throughout the eastern United States. White ash is the best known and preferred species. Technically, only wood from the black ash tree can be separated from the other species, and it is sometimes sold separately and referred to as brown ash by lumbermen. White ash ranges from the Great Plains east and from southern Canada south, with the exception of the lower Mississippi River Delta and coastal plains area. The tree prefers deep, moist, fertile upland soils and is usually a scattered tree associated with many other species. The largest tree reported is over 8 feet in diameter at 4½ feet above the ground. Black ash ranges from southeastern Canada through the northern half of the eastern United States. It prefers moist areas. The largest tree reported is over 4 feet in diameter at 4½ feet above the ground. Green ash and pumpkin ash may be abundant on certain sites. Blue ash is normally a scattered tree. The lumber from these species is generally mixed with white ash and sold together. A lighter, soft- textured pumpkin ash, more common in the south, Chip Morrison Dan Cassens and white ash is sometimes sold separately. Wood Color and Texture Both color and texture vary substantially in ash Most ash in the Appalachian and southern region lumber. The earlywood pores are large and abruptly is fast growth. -

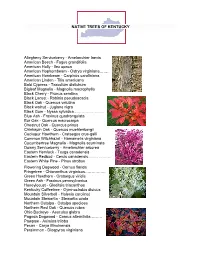

Native Trees of Kentucky

NATIVE TREES OF KENTUCKY Allegheny Serviceberry - Amelanchier laevis American Beech - Fagus grandifolia American Holly - Ilex opaca American Hophornbeam - Ostrya virginiana……. American Hornbeam - Carpinus caroliniana American Linden - Tilia americana Bald Cypress - Taxodium distichum Bigleaf Magnolia - Magnolia macrophylla Black Cherry - Prunus serotina Black Locust - Robinia pseudoacacia Black Oak - Quercus velutina Black walnut - Juglans nigra Black Gum - Nyssa sylvatica………………….. Blue Ash - Fraxinus quadrangulata Bur Oak - Quercus macrocarpa Chestnut Oak - Quercus prinus Chinkapin Oak - Quercus muehlenbergii Cockspur Hawthorn - Crataegus crus-galli Common Witchhazel - Hamamelis virginiana Cucumbertree Magnolia - Magnolia acuminata Downy Serviceberry - Amelanchier arborea Eastern Hemlock - Tsuga canadensis Eastern Redbud - Cercis canadensis……………… Eastern White Pine - Pinus strobus Flowering Dogwood - Cornus florida Fringetree - Chionanthus virginicus……………. Green Hawthorn - Crataegus viridis Green Ash - Fraxinus pennsylvanica Honeylocust - Gleditsia triacanthos Kentucky Coffeetree - Gymnocladus dioicus Mountain Silverbell - Halesia carolina) Mountain Stewartia - Stewartia ovata Northern Catalpa - Catalpa speciosa Northern Red Oak - Quercus rubra Ohio Buckeye - Aesculus glabra Pagoda Dogwood - Cornus alternifolia……… Pawpaw - Asimina triloba Pecan - Carya illinoinensis Persimmon - Diospyros virginiana Pignut Hickory - Carya glabra Pin Oak - Quercus palustris Red Buckeye - Aesculus pavia Red Maple - Acer rubrum River Birch - Betula nigra……………………. -

Bronze Birch Borer: a Toronto Master Gardeners Guide

Bronze Birch Borer: A Toronto Master Gardeners Guide The bronze birch borer (Agrilus anxius) is a beetle native to North America. The borers? larval feeding tunnels under the bark girdle the trunk or branch of the tree and interrupt the flow of nutrients and sap which eventually leads to the tree?s starvation. Older trees or those weakened by environmental stress or other insect infestations are most susceptible to attack. The adult bronze birch borer is a slender, olive-bronze, 10 mm long beetle. The larva is flat-headed, white and 12 mm long. The bronze birch borer can be a serious pest of several species of birch: white or paper birch (Betula papyrifera), grey birch (B. populifolia), and European birch (B. pendula). Symptoms of Bronze Birch Borer The first signs of damage by the bronze birch borer are sparse, yellowing foliage and browning tips on the upper branches of the affected tree. The dieback starts at the top of the tree and works downward. Infested branches may show swollen ridges on the bark, indicating the locations of feeding galleries (conspicuous swollen areas on the trunk are caused by the healing process of a survivor tree). D-shaped exit holes in the bark are a definite sign of the emergence of adult borers. Besides being more resistant to the Birch leafminers also turn the leaves of birch trees brown, but their damage Bronze Birch Borer. river birch (Betula nigra) features peeling bark which adds shows up throughout the tree, not only at the top. Also, although the birch to its interest in all seasons. -

Bronze Birch Borer by the Bartlett Lab Staff Directed by Kelby Fite, Phd

RESEARCH LABORATORY TECHNICAL REPORT Bronze Birch Borer By The Bartlett Lab Staff Directed by Kelby Fite, PhD The bronze birch borer (Agrilus anxius) is a native pest to North America. This insect is found in southern Canada and the northern United States and is a serious pest of native white or paper birch and the European white birch. Bronze birch borer attacks are more frequent on ornamental birches planted in the urban environment than native birches growing in natural forests. Damage Bronze birch borer larvae cause significant feeding injury by producing tunnels beneath the Bronze birch borer is considered an opportunistic pest bark layer. The winding tunnels in the cambium since it usually attacks trees that are weakened due to cause girdling of the stems that disrupts water and drought, stem decay, heavy pruning, and prolonged nutrient transport. Borer larvae produce D-shaped defoliation. Stem and twig dieback that begins in the exit holes in the outer bark as they emerge from upper tree canopy indicate symptoms of tree stress dead or dying stem tissue (Figure 2). (Figure 1). Stressed trees attract bronze borer adults that lay eggs along the main stem and crotches of large Figure 2: D-shaped exit holes on stem branches. Rapid tree dieback and decline ensues once borers invade dead and dying stem tissue. Figure 1: Stem and twig dieback associated with bronze birch borer Description The adult bronze birch borer beetle is flat, elongate in shape, and olive-green to black with a metallic bronze Page 1 of 2 Figure 3: Bronze birch borer adult Control Healthy, vigorous birches are most resistant to bronze birch borer attack. -

Sharpening Observation Skills This Photo Guide Is Part of a Diagnostic Set

BORERS: emerald ash borer & other significant Agrilus species (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) Agrilus spp. all have a characteristic “bullet” or cylindrical shape. Agrilus planipennis Agrilus Agrilus Agrilus Agrilus bilineatus anxius auroguttatus biguttatus emerald ash borer (EAB) twolined chestnut borer bronze birch borer INVASIVE. Metallic green with bronze goldspotted oak borer oak splendor beetle NATIVE. Metallic bronze-black NATIVE. Metallic bronze-black undertones; rarely bluish-green, bluish NATIVE (southeastern Arizona). EXOTIC (not known to be in to dark blue with two distinct with reddish, greenish or or coppery-red. Dorsal abdomen is Metallic dark green with six North America). Similar in white-yellow pubescent purplish undertones. Dorsal bright, coppery-red. Antennal segments gold spots on elytra. appearance to EAB. Metallic 1–3 cylindrical, segments 4–11 serrate. stripes down elytra. Dorsal abdomen is bronze-black. Length: ~10 mm medium green with bronze abdomen is bronze-black. Length: 10–13 mm (generally larger undertones, rarely blue or Length: 5.5–13 mm HOSTS: oaks (Quercus spp.) Length: 4.2–9.5 mm than native Agrilus spp.) gold, and two distinct white HOSTS: birch (Betula spp.) preference for species in red spots on the elytra. HOSTS: oaks (Quercus HOSTS: ash (Fraxinus spp.) oak group. Length: 9–12 mm spp.) chestnut, American INVASIVE (southern California). hornbeam, beech, eastern CA HOSTS: coast live oak, HOSTS: oaks (Quercus spp.), hop hornbeam California black oak, canyon same hosts as the native live oak twolined chestnut borer sharpening observation skills This photo guide is part of a diagnostic set. Visit www.FirstDetector.org for more SHARPENING OBSERVATION SKILLS materials. emerald ash borer “green” look-alikes sweat sharpshooter emerald trogossitid six-spotted dogbane St.