Cotton Corridors Final Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ooo- Memo No.2098/MP-SAND/KNL/2019, Dated: 24-07-2019

GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND GEOLOGY Office of the Deputy Director of Mines and Geology, Kurnool. -ooo- Memo No.2098/MP-SAND/KNL/2019, Dated: 24-07-2019 Sub:- Mines and Quarries - Six Mining plans for specified sand bearing areas i.e., 1) over an extent of 2.500 Hectares in Nagaladinne Sand Reach, Tungabhadra River, Nagaladinne Village, Nandavaramu Mandai, Kurnool District, 2) over an extent of 4.800 Hectares in Gudikambali Sand Reach-!, Tungabhadra River, Gudikambali Village, Kowthalam Mandai, Kurnool District, 3) over an extent of 4.950 Hectares in Gudikambali Sand Reach-II, Tungabhadra River, Gudikambali Village, Kowthalam Mandai, Kurnool District, 4) over an extent of 4.800 Hectares in Gudikambali Sand Reach-III, Tungabhadra River, Gudikambali Village, Kowthalam Mandai, Kurnool District, 5) over an extent of 4.200 Hectares in Nadichagi Sand Reach-I, Tungabhadra River, Nadichagi Village, Kowthalam Mandai, Kurnool District and 6) over an extent of 2.780 Hectares in Nadichagi Sand Reach-II, Tungabhadra River, Gudikambali Village, Kowthalam Mandai, Kurnool District - Six Mining plans prepared by the Assistant Geologist, Office of the Assistant Director of Mines and Geology, Kurnool - Mining Plans - Approved -Regarding. Ref:- 1) G.O.Ms.No: 56 of Industries & Commerce (M.II) Dept., Dated: 30.04.2016. 2) Prodgs.No: 28594/P.RQP/2001, dt: 13.05.2016 of the Director of Mines and Geology, Hyderabad. 3) Letter No: 267/Sand/2016, Dated: 23.07.2019 from the Asst. Director of Mines and Geology, Kurnool. -coo- In the reference 2nd cited, the Assistant Director of Mines and Geology, Kurnool has submitted six mining plans prepared by the Asst. -

District Census Handbook, Kurnool, Part XIII a & B, Series-2

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DI$TRiCT CENSUS HANDBOOK KURNOOL PARTS XIII-A & B VILLAGE 8: TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT .' S. S. JAVA RAO OF Tt\E '''DIAN ADMINiSTRATIVE S£RVlCE DIRECTOR OF CE"SU~ .OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRAD£SH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 19" SRI RAGHAVENDRASWAMY SRI NDAVANAM AT MANTRALAYAM The motif presented on the cover page represents 'Sri R8ghavendraswamy Brindavanam' at Mantral, ya,,7 village in Yemmiganur taluk of K'Jrnool district. At Mafitra Ifl yam, ever/ yt:ar in the month of Sravana tAugust) on th~ secon I day of th~ dark fortnigf-it (Bahula Dwitiya) the 'ARADHANA' of Sri Raghavendraswamy (the day on which the saht bJdily entered th1 B rindavan3m) is celebrated with great fervour. Lakhs of people throng Mantra/ayam on this day for the ineffalJ/e ex perience of the just b~lfll therl1. Sri R ghavr::ndraswamy is one of the famous Peetadh'pithis (Pontiffs):md 17th in the line of succes sion from Sri Madhwacharya, the original founder of 'Dwaitha Philos3phy'. Th9 Swa 71iji took over the charge at the PEETHA in the year 1624 4. D. and made extensive tours all over the country and almost ruled the Vedantha Kingdom for 47 years. The Swamiji entered the B'fnddvanam at Mantra/ayam alive in the month of August, 1671. Th:! Briodavanam in which lies the astral body cf the Saint Raghavendraswamy in TAPAS (medJtation, is a rectanfJular black granite stone resting on KURMA (tof!oisf;) carved tn stone. It faces the id']( of S" Hanuman installed by the Saint himself. -

Geomysore Services (India) Pv1~.Ltd

41 Cm) KOfnool, " GEOMYSORE SERVICES (INDIA) PV1~.LTD. GMSl-ML-Jonnagiri_ Six Monthly Report _ Let-MoEF _dt25.1 0.20 17 Mine Code: 27APRIIOOl Sub: Submission of Six Monthly Report of Compliance of Environmental Management at Jonnagiri Gold Project of M/s.Geomysore Services (India) Pvt.Ltd. in Tuggali Mandal, Kurnool District, Andhra Pradesh. Sir, We append herewith the Six Monthly Report of Compliance Status as mentioned as per Conditions Specified in 3. A. (xiii) of EC clearance vide letter no.F.No.J-11015/393/2008-IA.II (M) dt. 2.8.2010. This is for your kind perusal and records. Thank you, Yours faithfully for Geornysore Services (India) Pvt. Ltd. .J.,,_____ Chief Operating Officer Enclosure: Six Monthly Report in prescribed format. Copy to : 1) The Chief Conservator of Forests, Regional Office (SZ), Kendriya Sadan 4th Floor, E&F wings, 17thMain Road, 1st block Koramangala, Bangalore _ 560034 2) The Chairman, Central Pollution Board, Parivesh Bhawan CBD-Cum-office Complex, yst Arjun Nagar, New Delhi ~ The Joint Director, MoEF, Regional Office, South Eastern Zone, Nungambakkam, Chennai - 600 034. 4) The Member Secretary Andhra Pradesh State Pollution Control Board, Paryavarana Bhavan, A-III, Industrial Estate, Sanath Nagar, Hyderabad _ 500 018. 5) The Environmental Engineer, Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board, Regional Office, 1st Floor, Shankar Shopping Complex, Krishna Nagar Main Road, Kurnool _ 518 002 REGISTERED OFFICE & CORRESPONDENCE ADDRESS #627, Trinity,3rd Cross, 3rd Block,Koramangala, Bongalore:560034 Tel: +91 8040428400 Fax: +91 8040428401 Email: [email protected] (CIN: U74899KA1994PTC044275) • JONNAGIRI GOLD MINE COMPLIANCE REPORT ON ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT SIX MONTHLY REPORT FROM APRIL 2017 TO SEPTEMBER 2017 A. -

An Alternative Horticultural Farming in Kurnool District, Andhra Pradesh

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) Volume: 3 | Issue: 4 | May-Jun 2019 Available Online: www.ijtsrd.com e-ISSN: 2456 - 6470 Vegetable Cultivation: An Alternative Horticultural Farming in Kurnool District, Andhra Pradesh Kanthi Kiran, K1, Krishna Kumari, A2 1Research Scholar, 2Professor of Geography 1,2Sri Krishnadevaraya University, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh, India How to cite this paper: Kanthi Kiran, K | ABSTRACT Krishna Kumari, A "Vegetable In India nearly about 10.1 million hectares of area is under vegetable farming. Cultivation: An Alternative Horticultural The country is the largest producer of ginger and okra amongst vegetables and Farming in Kurnool District, Andhra ranks second in the production of Potatoes, Onions, Cauliflower, Brinjal, Cabbage Pradesh" Published in International etc. India’s diverse climate ensures availability of a variety of vegetables. As per Journal of Trend in Scientific Research National Horticulture Board, during 2015-16, India produced 169.1 million and Development metric tonnes of vegetables. The vast production base offers India, tremendous (ijtsrd), ISSN: 2456- opportunities for the export. During 2017-18 India exported fruits and 6470, Volume-3 | vegetables worth Rs. 9410.81 crores in which vegetables comprised of Rs Issue-4, June 2019, 5181.78 crores. Keeping the importance of vegetable farming in view, an pp.998-1002, URL: endeavour is made here to study the spatial patterns of vegetable crop https://www.ijtsrd.c cultivation in Kurnool District, Andhra Pradesh. om/papers/ijtsrd23 IJTSRD23980 980.pdf Keywords: Vegetable crops, Spatial Patterns, Horticultural farming Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and INTRODUCTION International Journal of Trend in Horticulture is the branch of agriculture, which deals with the cultivation of fruits, Scientific Research and Development vegetables, flowers, spices & condiments, plantation crops, Tuber crops and Journal. -

Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for Each District)

PRG. 179.11 (1") 750 MAHBUBNAGAR CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESH PART VII-B (12) ; - (12. Mahbubnagar District) A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh Price: Rs. 6·75 P. or l_5 Sh. 9 d. or $1·43c. 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Census, Publications of this State will bear Vol. No. II) PART I-A Gen eral Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics PART J-C Subsidiary Tables PART JI-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-IV] PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables [B-V to B-IX] PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special TabJes for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes ..PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Yillage_Survcy- Monograph-s (46) PART VJI-A (I) I Handicrafts Sl,Jrvey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VII-A (2) J PART VlI-B (1 to 20) ... Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for each District) PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration I (No! for sale) PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation J PART IX State Atlas PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City District Census H~llldbooks - (Separate Volume for each District) o "» r» 3: "C " . _... _ - ·': ~ ~ ~' , FOREWORD Although since the beginning of history, foreign travellers and historians have recorded the principal marts and entrepots of commerce in India and have even mentioned important festivals and fairs and articles of special excellence available in them, no systematic regional inventory was attempted until the time of Dr. -

Mekala Benchi of Aspari (Kurnool District): a Unique Neolithic Site in Andhra Pradesh: a Study

Mekala Benchi of Aspari (Kurnool District): A Unique Neolithic Site in Andhra Pradesh: A Study Yadava Raghu1 1. Department of History and Archaeology, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa – 516 005, Andhra Pradesh, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 16 July 2019; Revised: 18 September 2019; Accepted: 24 October 2019 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 7 (2019): 804-813 Abstract: Kurnool District in Rayalaseema region of Andhra Pradesh state is one of the richest zones of the prehistoric centers in the world and so it gives valuable information about its ancient culture. Archaeological evidences here cover a range of time periods from the present day and potentially extending back into the Pleistocene. From Captain Newbold’s time (1844) to very recent (2018) several archaeologists conducted investigations and some of them have conducted excavations in the study area. It is known on the basis of these explorations and excavations that evidence of the early man activities here are copious. In connection with the archaeological explorations I visited Mekala Benchi of Aspari, Kurnool district. In this backdrop, an attempt is made in this paper to portray the Neolithic Culture along with the rock-art depicted on the rock boulders of a hillock called boodida konda/boodidoni konda. The petro-glyphs depicted here include human figures; bulls; bulls associated with humans; elephant; horse riding; cupules and nandipadas etc. Stone tools and potsherds are also collected from the same site. Keywords: Mekala Benchi, Neolithic, Megalithic, Petroglyphs, Ethnoarchaeology, Conservation, Ceramics Introduction The food-procuring cultures were succeeded by food-producing cultures in different parts of the world. -

GOVERNMENT of ANDHRA PRADESH ABSTRACT Agriculture

GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH ABSTRACT Agriculture Department – Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (R.W.B.C.I.S)- Kharif, 2018 – Implementation of RWBCIS - Notification of Cluster/ District wise Crops - Orders – Issued. __________________________________________________________________________________ AGRICULTURE & COOPERATION (AGRI.II) DEPARTMENT G.O.MS.No. 54 Dated: 17-05-2018 Read the following: 1. G.O.Rt.No.305 , Agri. & Coop. (Agri.II) Dept., dated: 07.05.2018. 2. From the Special Commissioner of Agriculture, A.P., Guntur, Lr. No. Crop Ins. (2)10/2018 Dt. 15.05.2018. *** ORDER: The following Notification shall be published in the Andhra Pradesh State Extra-Ordinary Gazette dated:18.05.2018. NOTIFICATION In the G.O. first read above, Government have accorded administrative approval for implementation of Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) & Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) during Kharif, 2018 as recommended by the Financial Bid Processing Committee. 2. In the Letter second read above, the Special Commissioner of Agriculture, A.P., Guntur has requested the Government to issue NOTIFICATION orders for implementation of Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) during Kharif 2018 season. 3. The following contents are included in the Notification. Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) “Further, the claims under Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (R.W.B.C.I.S) shall be settled on the basis of the weather data furnished by the APSDPS/ State Govt. Mandal level Rain Gauge Stations/IMD Weather Stations for the notified crops & districts and not on the basis of individual declaration of crop damage Annavari Certificate/Gazette notification declaring the area Drought /Flood/ Cyclone affected etc., issued by the Government.” 4. -

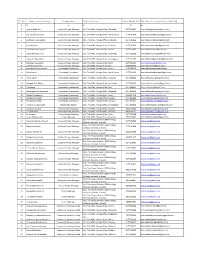

Meos & MIS Co-Ordinators

List of MEOs, MIS Co-orfinators of MRC Centers in AP Sl no District Mandal Name Designation Mobile No Email ID Remarks 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 Adilabad Adilabad Jayasheela MEO 7382621422 [email protected] 2 Adilabad Adilabad D.Manjula MIS Co-Ordinator 9492609240 [email protected] 3 Adilabad ASIFABAD V.Laxmaiah MEO 9440992903 [email protected] 4 Adilabad ASIFABAD G.Santosh Kumar MIS Co-Ordinator 9866400525 [email protected] [email protected] 5 Adilabad Bazarhathnoor M.Prahlad MEO(FAC) 9440010906 n 6 Adilabad Bazarhathnoor C.Sharath MISCo-Ord 9640283334 7 Adilabad BEJJUR D.SOMIAH MEO FAC 9440036215 [email protected] MIS CO- 8 Adilabad BEJJUR CH.SUMALATHA 9440718097 [email protected] ORDINATOR 9 Adilabad Bellampally D.Sridhar Swamy M.E.O 7386461279 [email protected] 10 Adilabad Bellampally L.Srinivas MIS CO Ordinator 9441426311 [email protected] 11 Adilabad Bhainsa J.Dayanand MEO 7382621360 [email protected] 12 Adilabad Bhainsa Hari Prasad.Agolam MIS Co-ordinator 9703648880 [email protected] 13 Adilabad Bheemini K.Ganga Singh M.E.O 9440038948 [email protected] 14 Adilabad Bheemini P.Sridar M.I.S 9949294049 [email protected] 15 Adilabad Boath A.Bhumareedy M.E.O 9493340234 [email protected] 16 Adilabad Boath M.Prasad MIS CO Ordinator 7382305575 17 Adilabad CHENNUR C.MALLA REDDY MEO 7382621363 [email protected] MIS- 18 Adilabad CHENNUR CH.LAVANYA 9652666194 [email protected] COORDINATOR 19 Adilabad Dahegoan Venkata Swamy MEO 7382621364 [email protected] 20 -

Sl. No. Name of the Employee Designation Office Address Land/ Mobile No

Sl. No. Name of the Employee Designation Office Address Land/ Mobile No. Mail Ids. (Individual/Office Mail Ids) 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Swarna Babu Rao Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Allagadda 9177101416 [email protected] 2 A.B. Vasantha Kumari Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Nandi Kotkur 9177101433 [email protected] 3 Dudekula Vijaya Gopal Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Koilkuntla 9177101424 [email protected] 4 Jalla Ayyanna Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Kodumur 9177101412 [email protected] 5 G. Mallikarjuna Swamy Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Dhone 9177101447 [email protected] 6 Gajula Ramajaneyulu Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Pattikanda 9177101459 [email protected] 7 Nagaruru Rajasekhar Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Yemmiganur 9177101405 [email protected]> 8 Kullamala Satyamma Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Adoni 9177101452 [email protected] 9 P. Radhakrishnaiah Assistant Project Manager O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Alur 9866550934 [email protected] 10 Animigalla Ramasunkadu Community Coordinator O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Dhone 9177904925 [email protected] 11 Molla Ismail Community Coordinator O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, Nandi Kotkur 9177904929 [email protected] 12 Pinjari Jaleel Community Coordinator O/o, The MMS, Velugu Office, -

GENERAL POPULATION TABLES ANDHRA PRADESH (Tables A-1 to A-4)

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 GENERAL POPULATION TABLES ANDHRA PRADESH (Tables A-1 to A-4) {.~ ~ ~~ ~8 a" ~ PEOPLE OR IENTED OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH Data Product Number 28-026-2001-Cen Book (E) (ii) Contents Pages 1. PREFACE v 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi 3. FIGURES AT A GLANCE vii-viii 4. MAP RELATING TO ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS ix 5. SECTION I : General Note 3-11 Census Concepts and Definitions 11-16 6. SECTION II: TABLE A-I: NUMBER OF VILLAGES, TOWNS, HOUSEHOLDS, POPULATION AND AREA 1. Fly Leaf 20-25 Statements 26-36 2. Diagram regarding Area and percentage to total Area 37 3. Map relating to Rural and Urban Population by Sex 2001 38 • 4. Map relating to Sex Ratio - 2001 39 5. Diagram regarding Area, India and States 2001 40 6. Diagram regarding Population - India and States - 200 1 41 7. Diagram regarding Population - Andhra Pradesh and Districts 200 1 42 8. Map relating to Density of PopUlation, 2001 43 9. Table A-I 45-142 Annexure - I 142-143 Annexure - II 144--146 10. Appendix and Annexure 147-150 7. TABLE A-2 : DECADAL VARIATION IN POPULATION SINCE 1901 1. Fly Leaf 153 Statements 153-158 2. Diagrams relating to Growth of Population 1901-2001 India and Andhra Pradesh 159-160 3. Table A-2 161-166 4. Appendix 167 (iii) Pages 8. TABLE A-3 : VILLAGES BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS 1. Fly Leaf 171 Statements 171-173 2. Table A-3 174-275 3. Appendix 276-302 9. TABLE A-4 : TOWNS AND URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS CLASSIFIED BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS IN 2001 WITH VARIATION SINCE 1901 1. -

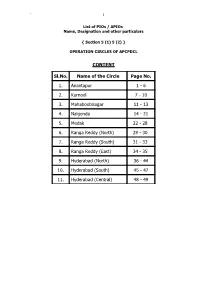

List of Pios / Apios Name, Designation and Other Particulars

` 1 List of PIOs / APIOs Name, Designation and other particulars { Section 5 (1) 5 (2) } OPERATION CIRCLES OF APCPDCL CONTENT Sl.No. Name of the Circle Page No. 1. Anantapur 1 - 6 2. Kurnool 7 - 10 3. Mahaboobnagar 11 - 13 4. Nalgonda 14 - 21 5. Medak 22 - 28 6. Ranga Reddy (North) 29 - 30 7. Ranga Reddy (South) 31 - 33 8. Ranga Reddy (East) 34 - 35 9. Hyderabad (North) 36 - 44 10. Hyderabad (South) 45 - 47 11. Hyderabad (Central) 48 - 49 ` 2 Name, Designation and other particulars of Public Information Officer { Section 5 (1) 5 (2) } OPERATION CIRCLE :: ANANTAPURAM Sl. Name of Appoin Contact phone number Name of the Officer Designation & Address No. Office ted As CELL OFFICE 08554-272941, 1 Smt.P.Padma I/c DE/Tech/CO/ Anantapur PIO 9440813194 272942 (O) Circle ATP 9490612309 08554-272941, 2 K.Appa Rao I/C AAE/Tech/CO/ Anantapur APIO 272942 3 T.R. Chnadra Mohan DE/Construction/ Anantapur PIO 9440813197 08554-270102 4 Construction P.Yuva bharathi AE/Technical/ Anantapur APIO __ 08554-270102 5 Division K.Kalidas ADE/Const-I / Anantapur PIO 9440813227 08554-270102 6 S.Rama Krishna ADE/Const-II / Anantapur PIO 9440813228 08554-270102 7 Smt.P.Padma DE/M&P/ Anantapur PIO 9440813196 08554-272121 8 R.Sreedevi AE/M&P/ Anantapur APIO …. 9 B.Sreenivasulu ADE/M&P/ Anantapur PIO 9440813224 10 J.R.Swetha Sub-Er/M&P/ Hindupur APIO 11 B.Kalyanchakravarthy ADE/M&P/ Kalyandurg PIO 9440813222 12 K.sreedevi Sub-Er/M&P/ Kalyandurg APIO M&P Division 13 N.Ramalinga Reddy ADE/M&P/ Gooty PIO 9440813239 14 M.Srinivasulu AE/M&P/ Gooty APIO 9440813236 15 C.Adinarayana -

Report No. 3 of 2015

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on General & Social Sector for the year ended March 2014 Government of Andhra Pradesh Report No. 3 of 2015 www.cag.gov.in Reference to Paragraph Page v ͳǦ About this Report 1.1 1 Profile of General and Social Sector 1.2 1 Office of Principal Accountant General (G&SSA) 1.3 2 Authority for audit 1.4 2 Planning and conduct of audit 1.5 3 Response of departments to Audit findings 1.6 3 Significant Audit observations 1.7 4 Performance Audits Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department ʹȂ 2 11 Tribal Welfare Department ͵Ȃ 3 41 Department for Women, Children, Disabled & Senior Citizens and other related departments ͶȂ 4 65 Compliance Audit ͷȂ Youth Advancement, Tourism and Culture Department 5.1 79 Minorities Welfare Department 5.2 89 Home Department 5.3 103 ȋȌ Reference to Paragraph Page Higher Education Department 5.4 113 Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department 5.5 122 Higher Education Department (Andhra Pradesh State Council of Higher Education) 5.6 131 School Education Department 5.7 135 Higher Education (Technical Education) Department (Rajiv Gandhi University of Knowledge Technologies) Ȁ 5.8 137 Reference to Paragraph Page 1.1 Department-wise break-up of outstanding Inspection 1.6 141 Reports and Paragraphs 1.2 Position of Pending Explanatory Notes as of January 2015 1.6 141 2.1 Number of units selected for detailed audit scrutiny 2.2.3.1 142 2.2 Shortage of equipment in test checked medical colleges and 2.3.3 143 teaching hospitals 2.3 Shortage