INNERVATE Leading Student Work in English Studies, Volume 7 (2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINUTES of the LA and EPHA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING THURSDAY 9 MAY 2019 Starting at 1.00 Pm

MINUTES OF THE LA AND EPHA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING THURSDAY 9 MAY 2019 starting at 1.00 pm In attendance Representing email address Clare Kershaw CK Director of Education [email protected] Alison Fiala Education and EY Lead Mid [email protected] Shamsum Noor Head of Statutory and Regulated [email protected] Services Julie Keating Education Access Manager [email protected] Lois Ashforth EPHA Dengie [email protected] George Athanasiou EPHA West Vice-Chair [email protected] Dawn Baker EPHA Mid Treasurer [email protected] Sue Bardetti EPHA Tendring South [email protected] Liz Benjeddi EPHA Billericay [email protected] Heidi Blakeley EPHA Wickford [email protected] Amanda Buckland EPHA South Woodham Ferrers [email protected] Garnett John Clements EPHA Uttlesford South [email protected] Anna Conley EPHA Witham [email protected] Dawn Dack EPHA Maldon [email protected] Emma Dawson EPHA Castlepoint and Rochford [email protected] Sarah Donnelly EPHA Halstead [email protected] Fiona Dorey EPHA Braintree [email protected] Richard Green Grove Wood Primary [email protected] Shelagh Harvey EPHA Brentwood [email protected] Nick Hutchings EPHA Vice-Chair/NE Chair [email protected] Chris Jarmain EPHA Epping Forest South Headteacher@st-johns- buckhursthill.essex.sch.uk Pam Langmead EPHA Professional Officer [email protected] Kate Mills EPHA Braintree [email protected] Nicola Morgan-Soane EPHA Mid Chair [email protected] Hayley O’Dea EPHA Rochford [email protected] Paula Pemberton EPHA Colchester East [email protected] Amanda Reid EPHA Chelmsford North [email protected] Suzy Ryan EPHA Colchester South [email protected] Karen Tucker EPHA Canvey Island [email protected] Jonathan Tye EPHA Harlow [email protected] Action 1. -

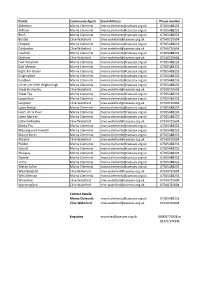

Parish Community Agent Email Address Phone Number Abberton

Parish Community Agent Email Address Phone number Abberton Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Aldham Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Birch Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Boxted Clive Wakeford [email protected] 07540720604 Chappel Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Colchester Clive Wakeford [email protected] 07540720604 Copford Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Dedham Clive Wakeford [email protected] 07540720604 East Donyland Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 East Mersea Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Eight Ash Green Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Fingringhoe Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Fordham Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Great and Little Wigborough Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Great Horkesley Clive Wakeford [email protected] 07540720604 Great Tey Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Langenhoe Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Langham Clive Wakeford [email protected] 07540720604 Layer Breton Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Layer-de-la-Haye Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Layer Marney Morna Clements [email protected] 07305488233 Little Horkesley Clive Wakeford [email protected] 07540720604 -

Colchester Local Highways Panel Meeting Agenda

COLCHESTER LOCAL HIGHWAYS PANEL MEETING AGENDA Date: Wednesday 6th June 2018 Time: 15:00 hrs Venue: Essex House, The Crescent, Colchester, CO4 9GN Chairman: CC Anne Brown Panel Members: CC Anne Turrell (Deputy), CC Member Kevin Bentley, CC Member Sue Lissimore, CC Member Julie Young, Cllr John Gili-Ross, Cllr Brian Jarvis, Cllr Dennis Willetts, Cllr Lyn Barton Officers: EH Sonia Church – Highway Liaison Manager EH Joe Hazelton - Highway Liaison Officer Secretariat: TBC Page Ite Subject Lead Paper m 1 Welcome & Introductions Chairman Verbal 2 Apologies for Absence Chairman Verbal P1 - 8 3 Minutes of meeting held on 20th March 2018 to be Chairman Report 1 agreed as a correct record/Actions from Minutes 4 Fixing the link overview Jane Verbal Thompson P9 - 14 5 Approved Works Programme 2018/19 Joe Hazelton Report 2 P15 - 30 6 Potential Schemes List for consideration of Panel in Joe Hazelton Report 3 2017/18: Traffic Management Passenger Transport Public Rights of Way Walking P31 - 37 7 Appendix Joe Hazelton Report 4 Colchester Rangers Report S106 Update Revenue Spend 8 Any other business: Joe Hazelton Verbal 9 Date of next meeting: Tuesday 11th September Chairman Verbal Any member of the public wishing to attend the Colchester Local Highways Panel (LHP) must arrange a formal invitation from the Chairman no later than 1 week prior to the meeting. Any public questions should be submitted to the Highway Liaison Officer no later than 1 week before the LHP meeting date; [email protected] COLCHESTER LOCAL HIGHWAYS PANEL MINUTES – TUESDAY 20TH MARCH 2018. 15:30 ESSEX HOUSE, THE CRESCENT, COLCHESTER, CO4 9GN Chairman: CC Anne Brown Panel Members: CC Anne Turrell (Deputy), CC Member Kevin Bentley, CC Member Sure Lissimore, CC Member Julie Young, Cllr John Gill-Ross, Cllr Brian Jarvis, Cllr Dennis Willetts, Cllr Lyn Barton Officers: EH David Gollop – Design Manager EH Joe Hazleton – Highway Liaison Officer Secretariat: Rochelle Morgan – Technical Assistant Item Owner 1. -

Colchester Holiday Park Colchester 50B Greenstead Lexden Osborne Street St

Route map for Hedingham service 50B (outbound) Colchester Holiday Park Colchester 50B Greenstead Lexden Osborne Street St. John's Town Railway Station Street Hythe Stanway The Pownall Britannia Crescent University of Essex Cemetery Queen Mary Gates Avenue Old Heath Lord Holland Road Crematorium Middlewick Chariot Drive Ranges Gymnasium Kingsford Buckley Place Cross Roads Stansted Road Monkwick Greenways Maypole Berechurch Baptist Church Green Hall Road Heckfordbridge Playing Fields Weir Lane The Cherry Kingsford Tree The Farm Roman Hill Folly Friday House Wood New Great Cut Les Bois Britain Haye Lane Fingringhoe The Layer-de-la-Haye Birch Fox Water Works Layer Birch Green Abberton Road Langenhoe Abberton Layer Breton Reservoir Essex Wildlife Trust Visitor Centre Abberton Reservoir St. Ives Road School Peldon Lane North Lower Village Road Stores 50B Copt Hall Lane Church Lane Great Wigborough Little Wigborough Old Kings Abbots Wick Lane Head School Mersea Lane South Island © OpenStreetMap 1.5 km 3 km 4.5 km 6 km set-0550B_(1).y08 (outbound) Route map for Hedingham service 50B (inbound) Colchester Holiday Park Colchester 50B Greenstead Lexden Osborne Street St. John's Town Railway Street Station Stanway Hythe The Pownall Britannia Crescent University of Essex Queen Mary Avenue Cemetery Gates Lord Holland Road Old Heath Chariot Crematorium Drive Gymnasium Middlewick Kingsford Buckley Ranges Place Cross Roads Stansted Road Monkwick Maypole Greenways Green Baptist Weir Heckfordbridge Playing Fields Church Lane The Cherry Kingsford Tree The Farm Roman Hill Folly Friday House Wood New Great Cut Les Bois Britain Haye Layer-de-la-Haye Lane The Birch Fox Water Works Layer Birch Green Abberton Road Langenhoe Abberton Layer Breton Reservoir Essex Wildlife Trust Visitor Centre Abberton Reservoir 50B St. -

N:\Reports\...\Colchester.Wp

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Colchester in Essex Report to the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions November 2000 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND This report sets out the Commission’s final recommendations on the electoral arrangements for the borough of Colchester in Essex. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Professor Michael Clarke CBE (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Kru Desai Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes CBE Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) © Crown Copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report no: 201 ii LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page LETTER TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE v SUMMARY vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 5 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 9 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 11 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 15 6 NEXT STEPS 41 APPENDICES A Final Recommendations for Colchester: Detailed Mapping 43 B Draft Recommendations for Colchester (May 2000) 49 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for Colchester is inserted inside the back cover of the report. LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND iii iv LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND Local Government Commission for England 28 November 2000 Dear Secretary of State On 30 November 1999 the Commission began a periodic electoral review of Colchester under the Local Government Act 1992. -

Philip Havens 1858-1895

HAVENS FAMILY DEEDS This collection of deeds referring to the Havens family of East Donyland and Wivenhoe was kindly loaned to the Wivenhoe History Group by Pat Green. The first three deeds refer to Wivenhoe. Beneath this is a list of all the deeds in chronological order which have either been transcribed, had an edited transcription or been summarised according to the content. The Wivenhoe deeds have all been transcribed and checked. The other deeds have been listed for research purposes but not thoroughly cross checked. Although most of the deeds consist of one long sentence they have been formatted into paragraphs for easier reading. WIVENHOE DEEDS 25 April 1866 Conveyance of freehold and covenant to surrender copyhold messuage and hereditaments situate at Wivenhoe in the County of Essex Mssrs Edward Parkes and William Moseley Tabrum To Philip Havens Esquire This Indenture made the twenty fifth day of April one thousand eight hundred and sixty six Between Edward Parkes of Colchester in the County of Essex Grocer and Jane Parkes his wife of the first part William Moseley Tabrum of the same place Grocer and Elizabeth Swinborne Tabrum his wife of the second part Philip Havens of Wivenhoe in the said County of Essex Esquire of the third part and Emmaretta Havens of Wivenhoe aforesaid Spinster Daughter of the said Philip Havens of the fourth part Whereas by Indentures of Lease and Release dated respectively the twenty sixth and twenty seventh days of September one thousand eight hundred and thirty two the Release being made between Joseph Fitch -

West Bergholt Neighbourhood Plan 27 - 114 E

Council Meeting Council Chamber, Town Hall, High Street, Colchester, CO1 1PJ Wednesday, 16 October 2019 at 18:00 Page 1 of 166 Information for Members of the Public Access to information and meetings You have the right to attend all meetings of the Council, its Committees and Cabinet. You also have the right to see the agenda (the list of items to be discussed at a meeting), which is usually published five working days before the meeting, and minutes once they are published. Dates of the meetings are available here: https://colchester.cmis.uk.com/colchester/MeetingCalendar.aspx. Most meetings take place in public. This only changes when certain issues, for instance, commercially sensitive information or details concerning an individual are considered. At this point you will be told whether there are any issues to be discussed in private, if so, you will be asked to leave the meeting. Have Your Say! The Council welcomes contributions and representations from members of the public at most public meetings. If you would like to speak at a meeting and need to find out more, please refer to the Have Your Say! arrangements here: http://www.colchester.gov.uk/haveyoursay. Audio Recording, Mobile phones and other devices The Council audio records public meetings for live broadcast over the internet and the recordings are available to listen to afterwards on the Council’s website. Audio recording, photography and filming of meetings by members of the public is also welcomed. Phones, tablets, laptops, cameras and other devices can be used at all meetings of the Council so long as this doesn’t cause a disturbance. -

All Saints Colchester Marriages 1609-1720 (Grooms) Groom Surname Groom 1St Status Bride 1St Bride Surname Status Marriage Date Notes ? Tho

All Saints Colchester marriages 1609-1720 (grooms) Groom surname Groom 1st Status Bride 1st Bride surname Status Marriage date Notes ? Tho. Single man Martha WOODWARD Single woman 05 Sep 1653 No groom's surname. [BR]USSE Samuell Jane BROCK 05 Sep 1677 Licence. Both of Feareing [FP]OSTER Edward Ann BARKER 15 Jun 1686 Bride of St Leonard's [LR]OWTH Ambrose Single man Sarah PURSLOW Single woman 15 Feb 1676/7 The L and R are over each other. Licence. ABBOT Gyles Widower Mary WEBB Widow 07 Mar 1697/8 Both of St Buttolph's ABEL James Anne WILLIAMS 01 Feb 1680/1 Licence. Both of St Leonard's ABLET Henry Single man Mary MILLAR Single woman 20 Feb 1701/2 Licence. Groom of S. Buttolphs, bride of Hadley ADAMS George Single man Anne SMALLEDGE Single woman 20 Feb 1678/9 A [= allegation ?]. Both of St Buttolphs ADAMS William Mary WRIGHT 31 Oct 1689 ADLER John Sara LANGHAM 15 Feb 1685/6 Licence. Both of St Leonard's AERIS George ? ? 20 Oct 1667 Groom of Sawkitt [ Salcott ?] AGAR John Phoebe GREENFEILD 25 Dec 1693 Bride of Greenstead AGNES Robert Ann TODD 07 Mar 1720/1 AILEWARD John Single man Mary BEMISH Single woman 24 Dec 1675 Licence. Both of Inworth No bride's surname. Year is given as 166 and is probably one ALAIS Petar Mary ? 03 Oct 1660 of 1660 to 1664. [ Alliss ? ]. ALCOCK James Mary FOAKES 31 Jul 1681 Both of West Marsey [ West Mersea ]. ALDERTON Anthony Single man Hannah ROGERS Single woman 31 Oct 1676 Licence. -

The London Gazette, Hth November 1960 7641

THE LONDON GAZETTE, HTH NOVEMBER 1960 7641 (27) 122 Fingringhoe Road, Old Heath, Colchester, (60) "Kimberley Nook" Sible Hedingham, Essex, Essex, by Vaughan. (Builders) Limited. by O. F. Fletcher of that address. (28) 227 High Street, Hounslow, Middx, by William (61) 36 and 38 Parklands Avenue, Groby, Leics, by Timpson Limited. N. J. and A. M. Bath, 36 Parklands Avenue (29) Plots 50-60 (inc.) Kings Avenue, Holland1 on Sea, aforesaid. Essex, by H. S. Scmtton, "Allambie" Thorpe (62) Land being O.S. Nos. 149 and part 147 and 148, Road, Clacton-on-Sea, Essex, and V. J. Barnard, Stanton, Suffolk, by W. J. Baker (Land Holdings) "Tarenga" Thorpe Road aforesaid. Limited. (30) "Phylbert" Dunton Road, Laindon, Essex, by P. M. Peters of that address. (31) Land adjoining "The Royal Oak" Clay Hill, LEASEHOLD Bushey, Herts, by J. Pritchard, 19 Clay Hill (:1) 58 Beechwood Road, Hackney, London E.8, by aforesaid. W. M. Balch, 27 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater, (32) 14 Chalfont Drive, Nottingham, by The Salva- London W.2, and R. M. Balch, " Quinneys" *ion Army Trustee Company. Wickham Bishops. Essex. (3'3) Land being part O.S. No. 84, Aynho, Northants, (2) Land and buildings on S.W. side of Crossbank by C. J. Pratt, 17 Aynho, Banbury, Oxon. Street and' land and buildings lying between (34) 188 Hampton Road, Ilford, Essex, and 26 and Crossbank Street, Park Street, Atlas Street, Atlas 28 Gwendoline Avenue, Upton Park, London Passage and King Street, Oldham, Lanes, by E.13, by H. F. Abbott, Stonely Hill Farm, Dronsfield Brothers Limited. Kimbolton, Hunts. -

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. -

Town/ Council Name Ward/Urban Division Basildon Parish Council Bowers Gifford & North

Parish/ Town/ Council Name Ward/Urban District Parish/ Town or Urban Division Basildon Parish Council Bowers Gifford & North Benfleet Basildon Urban Laindon Park and Fryerns Basildon Parish Council Little Burstead Basildon Urban Pitsea Division Basildon Parish Council Ramsden Crays Basildon Urban Westley Heights Braintree Parish Council Belchamp Walter Braintree Parish Council Black Notley Braintree Parish Council Bulmer Braintree Parish Council Bures Hamlet Braintree Parish Council Gestingthorpe Braintree Parish Council Gosfield Braintree Parish Council Great Notley Braintree Parish Council Greenstead Green & Halstead Rural Braintree Parish Council Halstead Braintree Parish Council Halstead Braintree Parish Council Hatfield Peverel Braintree Parish Council Helions Bumpstead Braintree Parish Council Little Maplestead Braintree Parish Council Little Yeldham, Ovington & Tilbury Juxta Clare Braintree Parish Council Little Yeldham, Ovington & Tilbury Juxta Clare Braintree Parish Council Rayne Braintree Parish Council Sible Hedingham Braintree Parish Council Steeple Bumpstead Braintree Parish Council Stisted Brentwood Parish Council Herongate & Ingrave Brentwood Parish Council Ingatestone & Fryerning Brentwood Parish Council Navestock Brentwood Parish Council Stondon Massey Chelmsford Parish Council Broomfield Chelmsford Urban Chelmsford North Chelmsford Urban Chelmsford West Chelmsford Parish Council Danbury Chelmsford Parish Council Little Baddow Chelmsford Parish Council Little Waltham Chelmsford Parish Council Rettendon Chelmsford Parish -

Essex Otter Survey 2007 Darren Tansley ESSEX Water for Wildlife Officer Wildlife Trust January 2008

Essex Otter Survey 2007 Darren Tansley ESSEX Water for Wildlife Officer Wildlife Trust January 2008 Protecting Wildlife for the Future Essex Otter Survey 2007 Darren Tansley - Water for Wildlife Below: Left is a fresh spraint with a black, tarry appearance. Right is an older spraint which is whiter and Background crumbly with obvious fish bones and scales visible. In the early 1950s otters Lutra lutra were widespread and common in Essex. Over the subsequent thirty years they experienced a massive decline with surveys in the mid 1980s suggesting they were extinct in the county. This population collapse was attributed to a decline in habitat quality and an increase in environmental contaminants accumulating in the food chain leading to poor reproductive success and survival rates. Long term post-mortem studies of otters, usually the victims of road traffic accidents, have revealed that accumulations of a number of toxins are higher in older males and juveniles than in breeding females. This is thought to be the result of mothers unloading toxins through their milk directly to their cubs. Males cannot pass toxins in this way so these accumulate over the course of their lifetime. While some chemicals have declined over the course of these studies (e.g., dieldrin, TDE and pp’DDE), organochlorines and PCBs have remained constant. Substantial deformities and reproductive failure are often the result of high levels of such toxins (Simpson, 2007). Another concern was the number of otters with bite wounds, up from 16% in 1996, to 52% in 2003. While bites from dogs were a significant contribution to deaths in cubs, most of the adult wounds were from other otters (Simpson 2007).