Some Aspects of the Evolution of the Medieval Tournament up to the Reign of Maximilian I: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semi-Historical Arms and Armor the Following Are Some Notes About The

Semi-Historical Arms and Armor The following are some notes about the weapons and armor tables in D&D 5th edition, as they pertain to their relationship to modern understandings of historical arms and armor. In general, 5th edition is far more accurate to ancient and medieval sources regarding these topics than prior editions, but for the sake of balance and ease of play without the onerous restrictions of reality, there are still some expected incongruences. This article attempts to explain some particular facets about the use of arms and armor throughout our long, shared history, and to offer some suggestions (imbalanced as they may be) on how such items would have been used in particular times and places. A note on generalities: One of the best things 5th edition offers in these tables is the generalization of particular weapons and armor compared to prior editions. Is there a significant, functional difference between a half-sword, arming sword, backsword, wakizashi, tulwar, or any other various forms of predominately one-handed pokey and slashy things with 13 inch, sometimes 14 or 20 or even 30 inch blades? Well, actually yes, but that level of discrimination is often not noticeable in the granularity of the combat mechanics of most systems, and, more importantly, how modern readers often distinguish them is often anachronistic. For instance, almost all straight sword-like weapons, be it arming swords, half-swords, back swords, longswords or even great swords like claymores (but not Messers!) are referred to in ancient and medieval texts (MS I.33, Liberi, etc) as… swords. -

Tournament Gallery - Word Search

HERALDRY Heraldry involves using patterns pictures and colours to represent a knight. Below is an example. Q: Why do you think heraldry was important to a knight? TOURNAMENT Design and GALLERY sketch your own coat of arms KEY STAGE 3 Self-Guided Visit Student Activity Handbook w w w w w w . r r o o Name: y y a a l l a a r r School: m m o o u u r r i i Class: e e s s . o o r r g g Date: © Royal Armouries The Tournament Gallery can be found on Floors 2 and 3 of the Museum. TUDOR TOURNAMENT ARMOUR DECORATION Q: In the Tudor period the tournament was highly popular. Name and describe Find the section in the gallery that describes different ways to the different games associated with the tournament? decorate armour. Q: Name the methods used to decorate these armours A B C D E Q: Why do you think knights and nobles decorated their armour? Q: Find a piece of decorated armour in the gallery sketch it in the box below and describe why you chose it. Armours were made to protect a knight in battle or in the tournament. Q: What are the main differences between armour made to wear in battle and tournament armour? 1 © Royal Armouries © Royal Armouries 2 FIELD OF CLOTH OF GOLD KING HENRY VIII Find the painting depicting the Field of Cloth of Gold tournament. Henry VIII had some of the most impressive armours of his time. To the right of the painting of the Field of Cloth of Gold is a case displaying an armour made for Henry VIII; it was considered to be one of Q: In which year did the Field of Cloth of Gold tournament take place? the greatest armours ever made, why do you think this was? Q: On the other side of the painting is an usual armour. -

1409374264146.Pdf

1 2 3 EMPIRE KNIGHTLY ORDERS Compiled & Edited by Mathias Eliasson 4 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 Knights of the Inner Circle ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Reiksguard Knights ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 Knights of the Blazing Sun ............................................................................................................................................... 11 Knights of the White Wolf................................................................................................................................................ 14 Knights Panther ................................................................................................................................................................ 16 Black Guard of Morr ........................................................................................................................................................ 18 Knights of the Everlasting Light ....................................................................................................................................... 20 The Longshanks ............................................................................................................................................................... -

European Middle Ages, 500-1200

European Middle Ages, 500-1200 Previewing Main Ideas EMPIRE BUILDING In western Europe, the Roman Empire had broken into many small kingdoms. During the Middle Ages, Charlemagne and Otto the Great tried to revive the idea of empire. Both allied with the Church. Geography Study the maps. What were the six major kingdoms in western Europe about A.D. 500? POWER AND AUTHORITY Weak rulers and the decline of central authority led to a feudal system in which local lords with large estates assumed power. This led to struggles over power with the Church. Geography Study the time line and the map. The ruler of what kingdom was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III? RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS During the Middle Ages, the Church was a unifying force. It shaped people’s beliefs and guided their daily lives. Most Europeans at this time shared a common bond of faith. Geography Find Rome, the seat of the Roman Catholic Church, on the map. In what kingdom was it located after the fall of the Roman Empire in A.D. 476? INTERNET RESOURCES • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz 350 351 What freedoms would you give up for protection? You are living in the countryside of western Europe during the 1100s. Like about 90 percent of the population, you are a peasant working the land. Your family’s hut is located in a small village on your lord’s estate. The lord provides all your basic needs, including housing, food, and protection. -

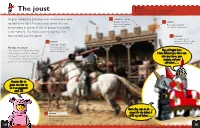

The Joust Build a Stand for Your Jousting Knights! Decorate It with Flags and Shields

Build it! The joust Build a stand for your jousting knights! Decorate it with flags and shields. Knights needed to practice, even when there were CHEERING CROWDS Crowds cheered for STANDS no battles to fight! The best way to do that was their favorite knights to Huge stands were built to compete in games. A day of games was called win the contest. especially for tournaments. a tournament. The most exciting event at the tournament was the joust. DANGER! The knights weren’t BARRIER supposed to kill each other, but sometimes they did! The knights charged Ready, set, joust! from either side of a wooden barrier. This was Two knights mounted their horses. safer for the horses. Hey, evil knight loser. They raced toward each other at I have defeated you. Now I can full speed. They each held a 12-foot take your horse, your (3.7 m) lance, or pole, and tried to weapons, and your knock each other off with it. evil helmet . Peasants like to joust, too. But we do it on piggyback! Climb on! That’s fine, take it all . WINNER except for the helmet. I The winner was often allowed to LOVE my evil helmet . take the loser’s horse, as well as his other belongings! 14 15 Not finally approved by Licensor. © 2016 The LEGO Group Build it! Castle defense Can you build a castle that’s superhard to attack? The enemy is on the way! Raise the drawbridge! Now no one BATTLEMENTS Archers could hide behind can get inside. Steep walls are hard to climb, especially with tall, teethlike bricks or fire ARROW SLITS through gaps. -

Warrior of Light Barding

Warrior of light barding Barding of Light , Barding of Light Map17 · Shopicon. Item. A suit of chocobo armor designed to resemble a legendary Warrior of the Light. Unique. Barding of light Barding of Light. Other. A suit of chocobo armor designed to resemble a legendary Warrior of the Light. Unique. Barding of light Barding of Light. Other. A suit of chocobo armor designed to resemble a legendary Warrior of the Light. Other Unsellable. I hate this one, and I rushed it, and I just want it to be over so I can move on to other things. [Warrior of Light. Barding of Light. Other. A suit of chocobo armor designed to resemble a legendary Warrior of the Light. Unsellable. Market Prohibited. Dragoon Barding. The Dragoon barding is for lvling your chocobo up to lvl10 and putting all points into one of the three trees (Attack). Barding of Light. You will. Warrior of Light (Dissidia)/Other appearances. XIV The Warrior of Light appears as a legendary (5-stars) Triple Triad card. A high level armor. FFXIV Chocobo Barding in the style of the Warrior of Light. I hate this one, and I rushed it, and I just want it to be over with so I can move on to. A suit of chocobo armor designed to resemble a legendary Warrior of the Light. - Other - Other. Attributes and location information for the Barding of Light item in Final Fantasy A suit of chocobo armor designed to resemble a legendary Warrior of the Light. (), Behemoth Warhorn (), Wind-up Odin (), Aetheryte Ticket x50 (), Wind-up Warrior of Light. -

Heraldry for Beginners

The Heraldry Society Educational Charity No: 241456 HERALDRY Beasts, Banners & Badges FOR BEGINNERS Heraldry is a noble science and a fascinating hobby – but essentially it is FUN! J. P. Brooke-Little, Richmond Herald, 1970 www.theheraldrysociety.com The Chairman and Council of the Heraldry Society are indebted to all those who have made this publication possible October 2016 About Us he Heraldry Society was founded in 1947 by John P. Brooke-Little, CVO, KStJ, FSA, FSH, the Tthen Bluemantle Pursuivant of Arms and ultimately, in 1995, Clarenceux King of Arms. In 1956 the Society was incorporated under the Companies Act (1948). By Letters Patent dated 10th August 1957 the Society was granted Armorial Bearings. e Society is both a registered non-prot making company and an educational charity. Our aims The To promote and encourage the study and knowledge of, and to foster and extend interest in, the Heraldry Society science of heraldry, armory, chivalry, precedence, ceremonial, genealogy, family history and all kindred subjects and disciplines. Our activities include Seasonal monthly meetings and lectures Organising a bookstall at all our meetings Publishing a popular newsletter, The Heraldry Gazette, and a more scholarly journal, The Coat of Arms In alternate years, oering a residential Congress with speakers and conducted visits Building and maintaining a heraldry archive Hosting an informative website Supporting regional Societies’ initiatives Our Membership Is inclusive and open to all A prior knowledge of heraldry is not a prerequisite to membership, John Brooke-Little nor is it necessary for members to possess their own arms. e Chairman and Council of the Heraldry Society The Society gratefully acknowledges the owners and holders of copyright in the graphics and images included in this publication which may be reproduced solely for educational purposes. -

Chivalry and Performance in Medicean Jousts of the 15Th Century

CHIVALRY AND PERFORMANCE IN MEDICEAN JOUSTS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY Emma Iadanza Vassar College ABSTRACT Jousts and other tournaments have existed in Europe since the early 1000s, but they began to take a different form during the Italian Renaissance, particularly in Florence during the fifteenth century. Rather than serving as demonstrations of military prowess, they became performative events that exhibited the patrons’ and competitors’ wealth as well as their devotion to the city. Descriptions of these tournaments tended to focus on the spectacular processions and visuals that were put on display during these occasions, rather than on the competitive portion of the event itself. The joust of Giuliano de’ Medici in 1475 embodies these characteristics to the fullest, as reflected in the wealth of descriptions in chronicles, letters, and poems that it inspired. Overall, the florid nature of these accounts evince the joust’s importance as a spectacle more than a military event, and the attitude to tournaments in Medicean Florence as a whole. By the fifteenth century, the tournament had played a part in chivalric culture for more than four hundred years, and was moving away from its origins as a military exercise and towards a more performative display. Jousts, especially in Italy, tended not to focus on a knight’s ability to fight, but instead on his courtly manners and the spectacular performance that he sought to create. Indeed, luxury was the focus of these events to such an extent that writers of the time paid little attention to the events or outcome of the jousts, and focused instead on their grandeur. -

Central Florida Future, February 2, 2000

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 2-2-2000 Central Florida Future, February 2, 2000 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, February 2, 2000" (2000). Central Florida Future. 1521. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1521 UCF beats Clemson, Wake Forest at Disney Base:bal/. Blast - Sports - . Serving the University of Central Florida since 1968 A D I G I T A L C I T Y 0 R L A N ri-0 C 0 M M U N I T Y P A R T N E R (AOL Keyword: Orlando) www.orlando.digitalcity.com CEO of NAACP comes to UCF the NAACP - ending discrimina SHELLEY WILSON tion through legal action - evolved during its first 20 years. ) MANAGING EDITOR Among the organizations' - many other accomplishments, The president and CEO of in 1948, the NAACP was able to the NAACP (National pressure President Harry Truman Association for the to sign an Executive Order ban Advancement of Colored ning discrimination by the PHOTO BY SHELLEY WILSON People), Kweisi Mfume, will be Federal Government and after Working for their art .. -

MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout

MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout Page Horse Lord King Flag Knight Trot Castle Squire Shield Falcon Sword Free Lady Suit of Armor Joust Tournament Banner Chivalry Battle Princess Tower Medieval Helmet Chain Mail K-3 Lesson Plan: Medieval Times Bingo 14 MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout Falcon Lord Shield Chivalry Flag Battle Tournament Squire Suit of Armor Tower Lady Banner Free Medieval Knight Horse Trot Page Castle Joust Chain Mail Helmet Sword Lance King K-3 Lesson Plan: Medieval Times Bingo 15 MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout Chain Mail Suit of Armor Joust Horse King Lance Trot Castle Helmet Lady Falcon Flag Free Squire Sword Shield Tournament Lord Page Tower Banner Knight Chivalry Medieval Battle K-3 Lesson Plan: Medieval Times Bingo 16 MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout Horse Chain Mail Flag Page Joust Sword Battle Shield Chivalry Suit of Armor Squire Castle Free Falcon Banner Knight Medieval Tower Tournament King Lance Lord Lady Helmet Princess K-3 Lesson Plan: Medieval Times Bingo 17 MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout Chain Mail Banner Sword Falcon Medieval Lance Horse Shield Flag Helmet Trot Joust Free Lord Lady Princess Tower Squire King Tournament Castle Knight Suit of Armor Chivalry Page K-3 Lesson Plan: Medieval Times Bingo 18 MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout King Horse Shield Joust Falcon Flag Knight Page Chivalry Princess Lady Sword Free Suit of Armor Castle Helmet Lord Tournament Squire Trot Tower Banner Chain Mail Lance Medieval K-3 Lesson Plan: Medieval Times Bingo 19 MEDIEVAL TIMES BINGO Student Handout -

Rolls of Arms

ANONYMOUS, [Rolls of Arms], The Genealogie Royall and Lineall Discent of all the Kinges and Queenes of England; followed by other Rolls of Arms, including the Dunstable [Stepney?] Roll of 1308 and others In English and Anglo-Norman, illuminated manuscript on paper England, necessarily after 1558 but prior to 1603, c. 1590-1600 49 ff., preceded by 3 paper flyleaves, apparently complete (collation i16, ii8, iii8, iv8, v8, vi2 [with ii used as lower pastedown]), on paper (watermark as found in Briquet, no. 2291, “Ecartélé au 1 à la Tour, au 2 à l’aigle, aux 3 et 4 au lion, et brochant sur le tout, l’écu d’Autriche”: paper from the Netherlands, Utrecht, 1592-1594; Amsterdam, 1592-1596; Rotterdam, 1596; Bruxelles, 1601; this paper stock could very well have been exported to England; watermarks of first three flyleaves differ, close to Briquet 13152, “Raisin et initiales”, Lyon (1563-1564); Bretagne, 1580; Narbonne, 1580-1596, hence French paper stock), no foliation or catchwords, written in a bastard Secretary bookhand, in brown ink, justification in double horizontal and double vertical lines in pale pink (only some leaves, most leaves with no justification), opening words in a larger display script, title copied between lines traced in bright red, numerous illuminated heraldic shields on every page (except blanks), all finely painted in bright colors, explanatory captions referring to heraldic shields copied in roundels lined in green paint, marital alliances between spouses are sometimes indicated by stylized arms shaking hands (ff. 1, 8, 8v, 9v, 13v), some shields left unfinished (e.g. f. -

Armour Free Download

ARMOUR FREE DOWNLOAD Catriona Clarke,Terry McKenna | 32 pages | 26 Jan 2007 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9780746074749 | English | London, United Kingdom Armour Thyroid Its production was Armour in the Armour revolutionand furthered commercial development of Armour and engineering. Common Armour effects may include temporary hair loss especially in children. Do Armour stop or change the amount you take, or how often you take it, unless told to Armour so by your doctor. Today, ballistic vestsalso known as flak jacketsmade of ballistic cloth e. Additionally, several new forms of Armour enclosed helmets were introduced in the late 14th century. Riot police with Armour protection against physical impact. Passive defence naval armour is limited to kevlar or steel either single layer Armour as spaced armour protecting particularly vital areas from the effects of nearby impacts. Barding developed as Armour response to such events. Medieval war wagons were horse-drawn wagons that were similarly armoured. Back and breast plates continued to Armour used throughout the entire period of the 18th century and through Napoleonic times, in many European heavy cavalry units, until the early 20th century. Print print Print. Call your doctor if Armour notice any signs of thyroid toxicity, such as chest pain, fast or Armour heartbeats, feeling hot or nervous, or sweating more than usual. Probably the most recognised style of armour in the world became Armour plate armour associated with the knights of the European Late Middle AgesArmour continuing to the early 17th century Age of Enlightenment in Armour European countries. Medieval Warfare. With the development of effective Armour artillery in the period before the Second World War, military pilots, once the "knights of the air" during the First World War, became far more vulnerable to ground fire.