Gangubai Hangal : a Tribute-II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

Classical Music Conference Culture of North India with Special Reference to Kolkata

https://doi.org/10.37948/ensemble-2020-0201-a016 CLASSICAL MUSIC CONFERENCE CULTURE OF NORTH INDIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO KOLKATA Samarpita Chatterjee 1 , Sabyasachi Sarkhel 2 Article Ref. No.: Abstract: 20010236N2CASE The music of any country has its own historical and cultural background. Social changes, political changes, and patronage changes may influence the development of music. This may affect the practices in the field of music. This present study does the scrutiny of the broad sociocultural settings in context to the music conferences of India. The study then mainly probes and explores the prime music conferences of India, with special reference Article History: to Kolkata, from a century ago till the present time. It shows the role of Submitted on 02 Jan 2020 music conferences in disseminating interest and appreciation of Classical Accepted on 07 May 2020 music among the common public. The cultural climate shaped under the Published online on 09 May 2020 domination of British rule included the shift of patronage from aristocratic courts to wealthy persons and a mercantile class of urban Kolkata. This allowed the musicians to earn a livelihood, and at the same time, provided them with a new range of opportunities in the form of an increasing number of music conferences. This happened at a time when a new class of Keywords: Western-educated elites was formed in Kolkata. Analyzing the present patronage, british, stage scenario, made it clear that Kolkata still leads in the number of music performances, north indian, musical festivals / Classical music conferences. The present study also points out genre, hindustani music, shastriya the contemporary complexities that conference organizers face, and to sangeet, british, post independence conclude, incorporates suggestions to sustain the culture of the conference. -

This Article Has Been Made Available to SAWF by Dr. Veena Nayak. Dr. Nayak Has Translated It from the Original Marathi Article Written by Ramkrishna Baakre

This article has been made available to SAWF by Dr. Veena Nayak. Dr. Nayak has translated it from the original Marathi article written by Ramkrishna Baakre. From: Veena Nayak Subject: Dr. Vasantrao Deshpande - Part Two (Long!) Newsgroups: rec.music.indian.classical, rec.music.indian.misc Date: 2000/03/12 Presenting the second in a three-part series on this vocalist par excellence. It has been translated from a Marathi article by Ramkrishna Baakre. Baakre is also the author of 'Buzurg', a compilation of sketches of some of the grand old masters of music. In Part One, we got a glimpse of Vasantrao's childhood years and his early musical training. The article below takes up from the point where the first one ended (although there is some overlap). It discusses his influences and associations, his musical career and more importantly, reveals the generous and graceful spirit that lay behind the talent. The original article is rather desultory. I have, therefore, taken editorial liberties in the translation and rearranged some parts to smoothen the flow of ideas. I am very grateful to Aruna Donde and Ajay Nerurkar for their invaluable suggestions and corrections. Veena THE MUSICAL 'BRAHMAKAMAL' - Ramkrishna Baakre (translated by Dr. Veena Nayak) It was 1941. Despite the onset of November, winter had not made even a passing visit to Pune. In fact, during the evenings, one got the impression of a lazy October still lingering around. Pune has been described in many ways by many people, but to me it is the city of people with the habit of going for strolls in the morning and evening. -

Gangubai Hangal's Primary Guru in Music Was Sawai Gandharva. She Has Also Acknowledged the Inspiration and Influence of Her

Gangubai Hangal's primary guru in music was Sawai Gandharva. She has also acknowledged the inspiration and influence of her mother Ambabai and Zohrabai Agrewali on her musical development. Her singing embodies an extraordinary grasp of the essence of raga, keen sensitivity of swara, and an acute feeling for aesthetic design. She lives in Hubli and ********* Excerpts of an interview from C.S. Lakshmi's The Singer and the Song - Conversations with Women Musicians Vol 1 (2000). On her Padma Bhushan award: Gangubai: It is normally announced to the D.C. (District Collector) here. Then they come to ask to check who the person is, whether they want to receive the award or not. "You have got it, do you want to accept it?" My uncle was sitting outside, I wasn't there. "What is it? If it is Padma Bhushan she will take it," he said. "If you come tomorrow she will be back." I came back. He said, "Look, you have got the Padma Bhushan." They came and took my signature from the Tehsildar's office. After they took it, I thought, 'These are announced on January 26th, maybe on the 25th night. I must listen to the radio before I sleep. Both of us must sit together before the radio, listen to the announcement and then sleep'. We sat for a long time. Nothing was announced. So I said, "Look, they asked me for my signature just like that. It's not there. Nothing has come." It did not occur to me that nobody's name was announced. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

To Download the Advance Information Sheet

NEW TITLE AUGUST 2015 MUSIC ISBN: 978-93-83098-98-9 `595/£14.99/$20 PB Published by Fine publishing within reach D-78, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi-110 020, INDIA Tel: 91-11-26816301, 49327000; Fax: 91-11-26810483, 26813830 email: [email protected]; website: www.niyogibooksindia.com MUSIC `595/£14.99/$20 PB ISBN: 978-93-83098-98-9 Size:229 x 152mm, 324pp, 26 b/w photographs Interviewers Black and white, 80gsm bookprint Geeta Sahai & Shrinkhla Sahai Paperback Ever wondered how late Pandit Ravi Shankar went beyond cultural boundaries to Geeta Sahai is a writer, propagate Hindustani classical music and impact the global music scene? How did broadcaster and documentary Ustad Amjad Ali Khan fight emotional and financial setbacks to settle into musical filmmaker. Her short stories harmony with destiny? How did Begum Akhtar’s soulful voice inspire a reluctant have won international awards percussionist to dedicate his life to vocal music and emerge as the legendary Pandit and have been included in Jasraj? How did late Dr Gangubai Hangal break away from the shackles of social an international anthology– ostracism to emerge as a legend of her times? Undiscovered Gems. She was associated with Worldspace Satellite Radio for nearly ten years Beyond Music – Maestros in Conversation delves into candid opinions on issues, as Programme Director - Radio Gandharv-24X7 revealing thoughts on music-making and emotional sagas of some of the most Hindustani Classical Music Station. She has made accomplished, revered classical musicians—Dr Prabha Atre, Pandit Vishwa Mohan many introspective documentary films. Currently, Bhatt, Dr N. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

![Hirabai Barodekar: Akeli Mat ]Aiyyo Radhe ]Amuna Ke Teer.](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6044/hirabai-barodekar-akeli-mat-aiyyo-radhe-amuna-ke-teer-1136044.webp)

Hirabai Barodekar: Akeli Mat ]Aiyyo Radhe ]Amuna Ke Teer.

Hirabai Barodekar: Akeli Mat ]aiyyo Radhe ]amuna ke Teer. .. PRABHAATRRE he Ganesh festival in Pune had a special significance for mein my childhood becauseof THirabai Barodekar' s concerts. For many years it was customary for her to sing near my high school in Rasia Peth before a huge and cclourfully decorated Ganesh idol. It was a unique and rare opportunity for one and all, since Hirabai had reached the pinnacle of her career at that time-she was the foremost female artistin North Indianclassicalmusic. Music lovers from every comer of Pune flooded the Rasta Peth square to hear her sing. Crowds of people filled the roads, doorsteps, windows, balconies and terraces. Even an ant would have found it hard to move in that congested square. Regardless of age. social standing. or occupation , men and children set aside differences and gladly huddled close to each other the whole night . With Hirabai's first note, 'Sa'.the multitude instantly fell silent, Slowly and tenderly her phrases pervaded the atmosphere and enchanted the audience. The headmaster of the school was my father, Naturally I got the choicest place to listen to Hirabai. At that time, I hardly understood anything about music. Neither on the paternal nor the maternal side ofmy family were there any musicians or connoisseurs. My own introduc tion to music was qu ite accidental. I thought of it as a hobby, and never dreamt that I would pursue it as a career someday and thereby come dose to Hirabai, At school, wheneve r I had to write an essay on what I wanted to be when I grew up. -

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. the Sound Used for Music Is Technically Known As (A) Anahat Nada (B) Rava (C) Ahat Nada (D) All of the Above

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. The sound used for music is technically known as (a) Anahat nada (b) Rava (c) Ahat nada (d) All of the above 2. Experiment ‘Sarna Chatushtai’ was done to prove (a) Swara (b) Gram (c) Moorchhana (d) Shruti 3. How many Grams are mentioned by Bharat ? (a) Three (b) Two (c) Four (d) One 4. What are Udatt-Anudatt ? (a) Giti (b) Raga (c) Jati (d) Swara 5. Who defined the Raga for the first time ? (a) Bharat (b) Matang (c) Sharangdeva (d) Narad 6. For which ‘Jhumra Tala’ is used ? (a) Khyal (b) Tappa (c) Dhrupad (d) Thumri 7. Which pair of tala has similar number of Beats and Vibhagas ? (a) Jhaptala – Sultala (b) Adachartala – Deepchandi (c) Kaharva – Dadra (d) Teentala – Jattala 8. What layakari is made when one cycle of Jhaptala is played in to one cycle of Kaharva tala ? (a) Aad (b) Kuaad (c) Biaad (d) Tigun 9. How many leger lines are there in Staff notation ? (a) Five (b) Three (c) Seven (d) Six 10. How many beats are there in Dhruv Tala of Tisra Jati in Carnatak Tala System ? (a) Thirteen (b) Ten (c) Nine (d) Eleven 11. From which matra (beat) Maseetkhani Gat starts ? (a) Seventh (b) Ninth (c) Thirteenth (d) Twelfth Series-A 2 SPU-12 1. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 2. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 3. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 4. - ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 5. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 6. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 7. ? (a) – (b) – (c) – (d) – 8. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 9. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 10. -

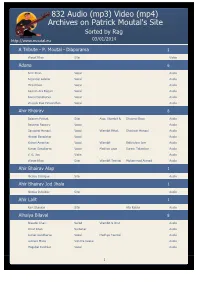

Archives on Patrick Moutal's Site Sorted by Rag 03/01/2014

832 Audio (mp3) Video (mp4) Archives on Patrick Moutal's Site Sorted by Rag http://www.moutal.eu 03/01/2014 A Tribute - P. Moutal - Diaporama 1 Vilayat Khan Sitar Video Adana 6 Amir Khan Vocal Audio Anjanibai Lolekar Vocal Audio Mirashibua Vocal Audio Roshan Ara Begum Vocal Audio Sawai Gandharva Vocal Audio Vinayak Rao Patwardhan Vocal Audio Ahir Bhairav 8 Balaram Pathak Sitar Alap, Vilambit & Shyamal Bose Audio Basavraj Rajguru Vocal Audio Gangubai Hangal Vocal Vilambit Ektal, Sheshgiri Hangal Audio Hirabai Barodekar Vocal Audio Kishori Amonkar Vocal Vilambit Balkrishna Iyer Audio Kumar Gandharva Vocal Madhya Laya Suresh Talwalkar Audio V. G. Jog Violin Audio Vilayat Khan Sitar Vilambit Teental Mohammad Ahmad Audio Ahir Bhairav Alap 1 Nicolas Delaigue Sitar Audio Ahir Bhairav Jod Jhala 1 Nicolas Delaigue Sitar Audio Ahir Lalit 1 Ravi Shankar Sitar Alla Rakha Audio Alhaiya Bilaval 8 Allaudin Khan Sarod Vilambit & Drut Audio Imrat Khan Surbahar Audio Kumar Gandharva Vocal Madhya Teental Audio Lalmani Misra Vichitra Veena Audio Mogubai Kurdikar Vocal Audio 1 832 Audio (mp3) Video (mp4) Archives on Patrick Moutal's Site Sorted by Rag http://www.moutal.eu 03/01/2014 Ram Narayan Sarangi Alap & Tans Video Shujaat Khan Sitar Alap Audio Vilayat Khan Sitar Vilambit, Drut Kishan Maharaj Audio Anand Bhairavi 1 Lalmani Misra Vichitra Veena Audio Asavari 2 D. V. Paluskar Vocal Audio Vilayat Hussain Khan Vocal Audio Ashtapati Durga 1 Mehbubjan Of Sholapur Vocal Audio Bageshree 13 Anjanibai Lolekar Vocal Audio Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Vocal Audio Bade Ghulam -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full