UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design Forward, Reverse Engineer

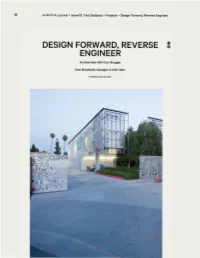

A+R+P+A Journal > Issue 01, Test Subjects> Projects > Design Forward, Reverse Engineer 0 DESIGN FORWARD, REVERSE 0 ENGINEER An interview with Cory Brugger How Morphosis manages to take risks. Published June 23, 2014 Morphosis office In Culver City. Photo: lwan Baan. Thorn Mayne's firm Morphosis has famously roused the ambitions of clients typically reluctant to take risks-even with government agencies such as the General Services Administration (GSA). ARPA .Journal spoke with Cory Brugger at Morphosis to see how the office uses practice as a site for experimentation. As Director of Design Technology, Cory tests ways to leverage technology for the practice, from parametrics to materials prototyping. Editor Janette Kim asked him how ideas about research have emerged within the methods, techniques, and processes of production at Morphosis. Janette Kim: What is the role of research at Morphosis? Cory Brugger: As a small practice (we still run like a ma-and-pa shop), we have been able to stay process-oriented, with small agile teams and Thorn involved throughout the entire project. In the evolution of the practice, design intent has always driven our projects. We start with a concept that evolves relative to the context (social, pragmatic, tectonic, etc.) of the project. R&D isn't something we're setting aside budgets for, but rather something that's always inherent and central to our design process. We find opportunities to explore technology, materials, construction, fabrication techniques, or whatever may be needed to realize the unique goals of each project. JK: This is exactly why I thought of Morphosis for this issue of ARPA .Journal. -

Bloomberg Center Design Fact Sheet

SEPTEMBER 13, 2017 Bloomberg Center Design Fact Sheet 02 PRESS RELEASE 05 ABOUT MORPHOSIS 06 BIOGRAPHY OF THOM MAYNE 07 ABOUT CORNELL TECH 08 PROJECT INFORMATION 09 PROJECT CREDITS 11 PROJECT PHOTOS 13 CONTACT 1 Bloomberg Center Press Release// The Bloomberg Center at Cornell Tech Designed by Morphosis Celebrates Formal Opening Innovative Building is Academic Hub of New Applied Science Campus with Aspiration to Be First Net Zero University Building in New York City NEW YORK, September 13, 2017 – Morphosis Architects today marked the official opening of The Emma and Georgina Bloomberg Center, the academic hub of the new Cornell Tech campus on Roosevelt Island. With the goal of becoming a net zero building, The Bloomberg Center, designed by the global architecture and design firm, forms the heart of the campus, bridging academia and industry while pioneering new standards in environmental sustainability through state-of- the-art design. Spearheaded by Morphosis’ Pritzker Prize-winning founder Thom Mayne and principal Ung-Joo Scott Lee, The Bloomberg Center is the intellectual nerve center of the campus, reflecting the school’s joint goals of creativity and excellence by providing academic spaces that foster collective enterprise and collaboration. “The aim of Cornell Tech to create an urban center for interdisciplinary research and innovation is very much in line with our vision at Morphosis, where we are constantly developing new ways to achieve ever-more-sustainable buildings and to spark greater connections among the people who use our buildings. With the Bloomberg Center, we’ve pushed the boundaries of current energy efficiency practices and set a new standard for building development in New York City,” said Morphosis founder and design director Thom Mayne. -

Dott. Arch. GUIDO ZULIANI

Dott. Arch. GUIDO ZULIANI CURRICULUM VITAE Dott. Arch. GUIDO ZULIANI AZstudio (Owner - Principal) 235 west 108th street #52 New York City, N.Y. 10025 - USA Tel. (1) 347-570 3489 [email protected] via Gemona 78 33100 Udine - Italy Tel. (39) 329-548 9158 Tel./ Fax +39- 0432-506 254 EDUCATION AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS 1998 ACCADEMIA DELLE SCIENZE, LETTERE ED ARTI “GLI SVENTATI” - Udine, Italy Elected Member 1982 ORDINE DEGLI ARCHITETTI DELLA PROVINCIA DI UDINE Register architect 1980 ISTITUTO UNIVERSITARIO D'ARCHITETTURA DI VENEZIA (IUAV) today UNIVERSITÀ IUAV DI VENEZIA Dottore in Architettura (Master equivalent) - Summa cum Laude ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE 1985 - Present THE COOPER UNION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE AND ART IRWIN S. CHANIN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE New York, NY 2009 - Present Professor of Architectural History 2005 - Present Professor of Architecture / Professor of Modern Architectural Concept Responsible for teaching Architectural Design II, Architectural Design IV, Thesis classes, the seminars in Modern Architectural Concepts, Analysis of Architectural Texts, Advanced Topics in Architecture 1991 - 2005 Associate Professor of Architecture 1986 - 1991 Visiting Professor of Architecture 2001 - Present Member of the Curriculum Committee Responsible for review and recommendations regarding the structure and the content of the school curriculum, currently designing the curriculum of the future post-professional Master Degree in Architecture of the Cooper Union. 2008 - Present SCHOOL OF DOCTORATE STUDIES - UNIVERSITÀ IUAV -

Boston Government Services Center: Lindemann-Hurley Preservation Report

BOSTON GOVERNMENT SERVICES CENTER: LINDEMANN-HURLEY PRESERVATION REPORT JANUARY 2020 Produced for the Massachusetts Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) by Bruner/Cott & Associates Henry Moss, AIA, LEED AP Lawrence Cheng, AIA, LEED AP with OverUnder: 2016 text review and Stantec January 2020 Unattributed photographs in this report are by Bruner/Cott & Associates or are in the public domain. Table of Contents 01 Introduction & Context 02 Site Description 03 History & Significance 04 Preservation Narrative 05 Recommendations 06 Development Alternatives Appendices A Massachusetts Cultural Resource Record BOS.1618 (2016) B BSGC DOCOMOMO Long Fiche Architectural Forum, Photos of New England INTRODUCTION & CONTEXT 5 BGSC LINDEMANN-HURLEY PRESERVATION REPORT | DCAMM | BRUNER/COTT & ASSOCIATES WITH STANTEC WITH ASSOCIATES & BRUNER/COTT | DCAMM | REPORT PRESERVATION LINDEMANN-HURLEY BGSC Introduction This report examines the Boston Government Services Center (BGSC), which was built between 1964 and 1970. The purpose of this report is to provide an overview of the site’s architecture, its existing uses, and the buildings’ relationships to surrounding streets. It is to help the Commonwealth’s Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) assess the significance of the historic architecture of the site as a whole and as it may vary among different buildings and their specific components. The BGSC is a major work by Paul Rudolph, one of the nation’s foremost post- World War II architects, with John Paul Carlhian of Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbot. The site’s development followed its clearance as part of the city’s Urban Renewal initiative associated with creation of Government Center. A series of prior planning studies by I. -

AIA LA Advocacy Platform

DESIGN- THINKING & REGIONAL AWARENESS The AIA LA advocacy platform AIA LA Our Challenges, Our Strengths Southern s a region, we have the best weather, the Awonderful and varied natural terrain and California some of the most creative and diverse people on the planet. It’s important to celebrate LA’s is an idyllic beauty and grace as often, as loudly and as clearly as we can. However, we’re also the place. hotbed for almost every physical, natural and human-made challenge the world has to offer including climate change, severe drought, an aging infrastructure, unaffordable housing, a concrete and treeless environment and, much of the time, unforgiving traffic as well as being in a region prone to earthquakes. Let’s face it. We don’t really have the money, the time and seldom do we seem to have a system in place that has the social and political capital necessary to engage and solve these issues and yet we know we can take on these challenges. A prime example of this is measure R that is making major inroads into our transportation network, so we know we can do it. However continuing to do business as usual - attempting to solve these vast and substantial problems in isolation from each other – will only yield marginal results, at best. By learning to ask better questions, and focusing our efforts on the future we’d like to see how we, as a region, could work together to identify more effective and aspirational solutions. As Architects we are accustomed to integrating complex criteria from multiple disciplines to elicit elegant solutions that satisfy fiscal, social and functional issues. -

Neri Oxman Material Ecology

ANTONELLI THE NERI OXMAN CALLS HER DESIGN APPROACH MATERIAL ECOLOGY— A PROCESS THAT DRAWS ON THE STRUCTURAL, SYSTEMIC, AND AESTHETIC WISDOM OF NATURE, DISTILLED AND DEPLOYED THROUGH COMPUTATION AND DIGITAL FABRICATION. THROUGHOUT HER TWENTY- ECOLOGY MATERIAL NERI OXMAN NERI OXMAN YEAR CAREER, SHE HAS BEEN A PIONEER OF NEW MATERIALS AND CONSTRUCTION PROCESSES, AND A CATALYST FOR DYNAMIC INTERDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATIONS. WITH THE MEDIATED MATTER MATERIAL GROUP, HER RESEARCH TEAM AT THE MIT MEDIA LAB, OXMAN HAS PURSUED RIGOROUS AND DARING EXPERIMENTATION THAT IS GROUNDED IN SCIENCE, PROPELLED BY VISIONARY THINKING, AND DISTINGUISHED BY FORMAL ELEGANCE. ECOLOGY PUBLISHED TO ACCOMPANY A MONOGRAPHIC EXHIBITION OF OXMAN’S WORK AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, NERI OXMAN: MATERIAL ECOLOGY FEATURES ESSAYS BY PAOLA ANTONELLI AND CATALOGUE HADAS A. STEINER. ITS DESIGN, BY IRMA BOOM, PAYS HOMAGE TO STEWART BRAND’S LEGENDARY WHOLE EARTH CATALOG, WHICH CELEBRATED AND PROVIDED RESOURCES FOR A NEW ERA OF AWARENESS IN THE LATE 1960S. THIS VOLUME, IN TURN, HERALDS A NEW ERA OF ECOLOGICAL AWARENESS—ONE IN WHICH THE GENIUS OF NATURE CAN BE HARNESSED, AS OXMAN IS DOING, TO CREATE TOOLS FOR A BETTER FUTURE. Moma Neri Oxman Cover.indd 1-3 9.01.2020 14:24 THE NERI OXMAN MATERIAL ECOLOGY CATALOGUE PAOLA ANTONELLI WITH ANNA BURCKHARDT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK × Silk Pavilion I Imaginary Beings: Doppelgänger Published in conjunction with the exhibition Published by Neri Oxman: Material Ecology, at The Museum of The Museum of Modern Art, New York Modern Art, New York, February 22–May 25, 2020. 11 West 53 Street CONTENTS Organized by Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator, New York, New York 10019 Department of Architecture and Design, www.moma.org and Director, Research and Development; and Anna Burckhardt, Curatorial Assistant, © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York 9 FOREWORD Department of Architecture and Design Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited on page 177. -

Architecture

April Press 15 Final Cranial_Layout 1 3/8/15 12:58 PM Page 16 architecture A new book by Chatham and New York City architect George Ranalli Below: Ranalli’s book complete with clamshell shows award-winning examples of buildings and industrial products case in a vibrant red – whose design vocabulary has roots in a longer craft tradition in design has the gravitas of treasured bible. and architecture. Ace Frehley, of the rock group Kiss, wanted a house in the Connecticut countryside that expressed his need for a dwelling that would provide some respite from waking up to find fans pressing their In Situ noses against his windows. By Rich Kraham In a new, lavishly illustrated book entitled In Situ , architect George K-Loft in Chelsea, Ranalli, who owns a home on Hudson Avenue in Chatham, sums New York City. up his theoretical positions on architectural projects that he has Living room, din - ing room and been involved in here, in New York City, and around the world. kitchen as seen These include large urban projects, additions, renovations to from the entry to major landmark buildings, interiors, new constructions and the master bed - houses in the landscape. Ranalli explains that the title of his book room is from the Latin meaning “in place,” and he stresses that buildings become iconic, not because some “starchitect” has created a stunning form plopped down on a site, but because the building fits and “responds lovingly to the specificities of place.” Apparently, a host of architectural critics feel the same way. Former New York Times critic Paul Goldberger, in discussing a Ranalli project in Rhode Island to convert a school into condos, wrote: “For all its modernity, this project is an architectural experience worthy of Ranalli designs tables and other Newport, and it connects us again to the architectural traditions furniture to go of this unusual city.” Ada Louise Huxtable, an architectural critic along with his with the Wall Street Journal, wrote that Ranalli’s Saratoga Avenue interior designs. -

Raimund Abraham: Rund Um Den Nullpunkt

Falter, Wien. Nr. 13 / 1986 Raimund Abraham: Rund um den Nullpunkt Ein Falter-Gespräch mit Raimund Abraham (New York - Wien), anfang der sechziger Jahre mit Hans Hollein und Walter Pichler Mitbegründer des ‚Austrian Phenomen’ einer neuen experimentellen Architektur und heute einer der führenden theoretischen Köpfe der Avantgarde für eine Architektur nach der Postmoderne. Der Anlaß: Seine Ausstellung ‚Stadtfragmente' im Otto Wagner-Archiv in Wien. Seine Gesprächspartner: Dietmar Steiner und Christian Reder, beide tätig an der Hochschule für angewandte Kunst in Wien. +++ Steiner: Was uns ‚Hinterbliebene' immer interessiert: Warum weg aus Wien, warum solange New York, warum nicht zurück. warum nicht woanders hin? Abraham: Das ist einfach zu beantworten. Ich fühlte mich plötzlich eingeengt, es gab da so einen Stillstand. Mein Studienkollege und zeitweiliger Arbeitspartner Friedrich St. Florian, der schon an der Rhode Island School of Design tätig war, hat mich dann, 1964, für eine kleine Ausstellung und ein Seminar eingeladen und dort hat man mir eben eine Professur angeboten und so bin ich geblieben. Zuerst war ich ein paar Monate in New York, dort habe ich Frederick Kiesler kennengelernt und er hat mir sein Atelier zur Verfügung gestellt, weil er krank war, und so habe ich zum ersten Mal diese Stadt erfahren. Das war wie eine Erlösung. Und in den zwanzig Jahren seither habe ich gelernt, wie der Abstand zur eigenen Kultur Sensibilitäten hervorruft, z.B. in Bezug auf die Muttersprache, die man ohne ihn nicht findet. Inzwischen hat sich New York wie jede andere internationale Stadt auch dem Innentourismus geopfert . Die Leute verlieren ihr Gesicht, die Stadt wird anonym. -

Paul Rudolph

PAUL RUD LPH Acknowledgments Program 13ll ' \ This booklet and the exhibi- Chicago architectural com- Exhibition Front cover: tion it accompanies are the munity to learn more about May 6-28, 1987, in the second- Overall perspective of a fourth in The Art Institute of his work through this exhibi- floor gallery of the Graham corporate office building for Wisma Dharmala Sakti. Chicago's Architecture in tion and his lecture at the Foundation for Advanced Jakarta , Indonesia, 1982 Context series, which is in- Graham Foundation. Studies in the Fine Arts, [no. 29). tended to highlight aspects We wish to thank Robert 4 West Burton Place, Chicago. of architecture that Bruegmann, Associate Pro- Graham Foundation hours: Back cover: Atrium perspective of a have not received sufficient fessor of Architecture and Monday through Thursday, corporate office building for critical attention. The current Art History at University of 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Wisma Dharmala Sakti, exhibition broadens that Illinois at Chicago, for his Jakarta, Indonesia, 1982 focus by concentrating on insightful essay and for work- Lecture [no. 32) . the current work of New York ing with Paul Rudolph to Paul Rudolph, "The Archi- © 1987 Graham Foundation architect Paul Rudolph, who, select the drawings for inclu- tectural Space of Wright, for Advanced Studies in the admittedly, has been pro- sion in the exhibition. We Mies, and Le Corbusier," May Fine Arts and The Art Institute foundly influenced by Chica- also wish to thank Ronald 6, 1987, the Graham Founda- of Chicago. All rights reserved. go architects Frank Lloyd Chin, for coordinating the tion Auditorium, 8:00 p .m. -

Lorcan O'herlihy,Faia a Distinguished Practice

Since founding his firm in 1994, Lorcan O’Herlihy, FAIA has utilized LORCAN architecture as a catalyst of change to shape and enrich the complex, O’HERLIHY,FAIA urban landscape of our contemporary city. The work of his firm, Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects (LOHA), is guided by a conscious understanding that A DISTINGUISHED architecture operates within a layered context of political, developmental, environmental, and social structures. With studios in Los Angeles and PRACTICE Detroit, LOHA has built over 90 projects across three continents. O’Herlihy and LOHA have produced work that has been published in over 20 countries and received over 100 awards throughout the years including the AIA Los Angeles firm of the year. The diverse work of the firm ranges from art galleries, bus shelters, and large-scale neighborhood plans, to large mixed-use developments, housing developments, and university residential complexes. Each project by LOHA exhibits O’Herlihy’s belief that artistry and bold design are key to building a vibrant, social space to elevate the human condition via the built environment. MARIPOSA1038 SL11024 BIG BLUE BUS STOPS O’Herlihy spent his formative years working at I.M. Pei Partners in New York and Paris on the addition to the Grand Louvre Museum. The LORCAN experience working on a project that harmoniously coupled art and O’HERLIHY,FAIA architecture was paramount to his design philosophy and installed a passion for aesthetic improvisation and composition. In addition, O’Herlihy A DISTINGUISHED also worked as a painter, sculptor, and furniture maker. The breath of scales—from being part of a design team for a large public art institution PRACTICE like the Louvre to intimately producing art and objects—melds his inclination for material exploration and formal inflection which form the basis of his eponymous firm, Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects [LOHA]. -

ANTHONY VIDLER CURRICULUM VITAE BA Architecture and Fine Arts, Hons.; Dipl

1 ANTHONY VIDLER CURRICULUM VITAE BA Architecture and Fine Arts, Hons.; Dipl. Arch., Cantab.; PhD. TU Delft. Professor, The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Citizenship: British. Permanent Resident, USA ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2001-present Professor, Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, The Cooper Union, NY. 2014-2018 Vincent Scully Visiting Professor of Architectural History, Yale University School of Architecture (Spring Semester). 2013 (Spring) Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton: Member, School of Historical Studies, 2013 -2014 Brown University: Visiting Professor of Humanities and Art History, 1998-2001: University of California Los Angeles: Professor of Art History and Architecture. 1982-1993: Princeton University: Professor of Architecture, William R. Kenan, Jr. Chair. 1972-1982: Princeton University: Associate Professor of Architecture. 1967-1972: Princeton University: Assistant Professor of Architecture. 1965-1967: Princeton University: Instructor in Architecture and Research Associate. ADMINISTRATIVE 2002-2013: Dean, School of Architecture, The Cooper Union 1993-2002: Chair, Department of Art History, UCLA 1997-1998 Dean, College of Art, Architecture, and Planning, Cornell University 1973-1993: Chair, PhD. Program, School of Architecture, Princeton University. 1980-1987: Director, European Cultural Studies Program, Princeton University. 1982-1993 Dean's Executive Committee, School of Architecture, Princeton -

Radical Austria Everything Is Architecture English

RADICAL RADICAL AUSTRIA EVERYTHING IS ARCHITECTURE ENGLISH AUSTRIA RADICAL AUSTRIA EVERYTHING IS ARCHITECTURE ENGLISH RADICAL AUSTRIA RADICAL AUSTRIA From the adage ‘Everything is architecture’ formulated EVERYTHING IS ARCHITECTURE by Hans Hollein, he and his Austrian contemporaries The experimental work by Austrian architecture collec- shape their vision of the world in all possible domains: tives and designers from the early 1960s to mid-1970s from inflatable shelters to performances, from fashion has been described as ‘the Austrian avant-garde’. to furniture and from television programs to cities of the This exhibition is dedicated to the mind-expan ding, future. Early on they start experimenting with cyber ne- boun dary-shifting and socially critical work of these tics, space travel, drugs, media and gender. Finding designers. Not accepting limitations of definitions inspiration in pop culture, they often organise them- and disciplines, they created buildings, environ ments, selves as improvising collectives, like the example set objects, fashion, performances, furniture and even by psychedelic rock groups. experiences. The combination of experiment and analysis makes the Works by groups such as Coop Himmelb(l)au, Austrian avant-garde one of the most radical move- Haus-Rucker-Co, Zünd-Up and independent designers ments of that time. Their topics are still relevant today: and artists such as Walter Pichler, Hans Hollein and addressing the relationship between man and machine, VALIE EXPORT are a reaction to social and techno lo- communication versus isolation and the desire to create gical developments at large as well as to the specific personal bubbles. The visions these activist designers Austrian context.