Review of Selected Infrastructure Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Committee

MINUTES PLANNING COMMITTEE 25 OCTOBER 2016 APPROVED FOR RELEASE ------------------------------------ MARTIN MILEHAM CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER I:\CPS\ADMIN SERVICES\COMMITTEES\5. PLANNING\PL161025 - MINUTES.DOCX PLANNING COMMITTEE INDEX Item Description Page PL164/16 DECLARATION OF OPENING 1 PL165/16 APOLOGIES AND MEMBERS ON LEAVE OF ABSENCE 2 PL166/16 QUESTION TIME FOR THE PUBLIC 2 PL167/16 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 2 PL168/16 CORRESPONDENCE 2 PL169/16 DISCLOSURE OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS 2 PL170/16 MATTERS FOR WHICH THE MEETING MAY BE CLOSED 2 PL171/16 8/90 (LOT 8 ON SP 58159) TERRACE ROAD, EAST PERTH – PROPOSED ALFRESCO AREA AND MODIFICATIONS TO HOURS AND SIGNAGE FOR APPROVED ‘LOCAL SHOP’ 3 PL172/16 MATCHED FUNDING BUSINESS GRANT – 2016/17 PROGRAM – BABOOSHKA BAR 18 PL173/16 EVENT – WELLINGTON SQUARE – CHINESE CULTURAL WORKS PRESENTS PERTH FESTIVAL OF LIGHTS 21 PL174/16 INVESTIGATION OF FOOD AND BEVERAGES PREPARATION WITHIN ALFRESCO DINING AREAS 28 PL175/16 EXPANDED CITY OF PERTH BOUNDARY – SUBIACO FOOD BUSINESSES – ALFRESCO AREAS (COUNCIL POLICY 14.4 – ALFRESCO DINING POLICY 2000) 36 PL176/16 PROPOSED STREET NAME FOR THE RIGHT OF WAY – 111-121 NEWCASTLE STREET PERTH 38 PL177/16 PROPOSED ENTRY OF GRAND CENTRAL HOTEL – 379 WELLINGTON STREET, PERTH IN THE CITY PLANNING SCHEME NO. 2 HERITAGE LIST 41 PL178/16 PROPOSED PERMANENT HERITAGE REGISTRATION OF P23847 EDITH COWAN’S HOUSE AND SKINNER GALLERY (FMR) 31 MALCOLM STREET PERTH, IN THE STATE HERITAGE REGISTER. 50 PL179/16 REVIEW OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT DRAFT TRANSPORT @ 3.5 MILLION - PERTH TRANSPORT PLAN 53 PL180/16 REVISED CYCLE PLAN IMPLEMENTATION PROGRAM 2016-2021 58 I:\CPS\ADMIN SERVICES\COMMITTEES\5. -

Parliamentary Debates (HANSARD)

Parliamentary Debates (HANSARD) THIRTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 2012 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thursday, 15 November 2012 Legislative Assembly Thursday, 15 November 2012 THE SPEAKER (Mr G.A. Woodhams) took the chair at 9.00 am, and read prayers. PARLIAMENT HOUSE — SOLAR PANELS INSTALLATION Statement by Speaker THE SPEAKER (Mr G.A. Woodhams): Members, I remain on my feet to provide you with two pieces of information. The Parliament has decided to install a set of solar panels on top of Parliament House. By the end of the year, Parliament will be generating its own electricity on site. There will be 72 panels in all, enough to provide energy to both legislative chambers. I might facetiously suggest that we always have enough light in this house! Mr T.R. Buswell: We’ve got enough hot air! The SPEAKER: Correct, minister! Several members interjected. The SPEAKER: Thanks, members. Hon Barry House, President of the Legislative Council, and I have been planning this project for quite some years. We believe that the location of the 72 solar array panels above this particular chamber, construction of which finished in 1904, will certainly reduce electricity costs in this place. Parliament will undertake other sustainable energy innovations with LED lighting, the use of voltage optimisers and the real time monitoring of electricity, gas and water use. I knew that members would find that information useful. COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AND JUSTICE STANDING COMMITTEE — INQUIRY INTO THE STATE’S PREPAREDNESS FOR THIS YEAR’S BUSHFIRE SEASON Extension of Reporting Time — Statement by Speaker THE SPEAKER (Mr G.A. Woodhams): I also indicate that I received a letter dated 14 November 2012 from the Chairman of the Community Development and Justice Standing Committee advising that the committee has resolved to amend the tabling date of the report on its inquiry into the state’s preparedness for this year’s fire season until 26 November 2012. -

New Perth Stadium Transport Project Definition Plan December 2012

new Perth Stadium Transport Project Definition Plan December 2012 Artist’s impression: pedestrian bridge location 0ii transport solution for the new Perth Stadium transport solution for the new Perth Stadium Artist’s impression: new Perth Stadium Station 03 contents key features 2 Appendix 1 19 Dedicated train services 2 Transport facilities to be funded Complementary bus services 3 by the Government Pedestrian connection to CBD 3 Appendix 2 19 Enhancing existing infrastructure 3 Indicative cashflow evolution of the transport solution 4 executive summary 6 Project Definition Outcomes 7 Infrastructure 15 Importance of rigour 16 Cost Estimates 16 Project Management 17 Staging 17 Cashflow 17 01 key features Passengers first. Holistic transport approach. Multiple transport options. The new Perth Stadium By applying the ‘tentacles of movement’ presents an opportunity for philosophy, spectators will be dispersed, rather than surging together in one the Public Transport Authority direction, ensuring fast and safe transfers (PTA) to concurrently develop and reducing the impacts on nearby the transport solution within residential and environmental areas. a new precinct at Burswood, Key features of the responsive and rather than retrofit it into a robust transport solution, to be delivered constrained space. for the start of the 2018 AFL season, include: Adopting the new Perth Stadium’s ‘fan first’ philosophy, the Transport Dedicated train services PDP reflects passenger needs and Six-platform Stadium Station for demands to create a ‘passenger first’ convenient loading and rapid transfers transport solution. to destinations. This will be achieved through Nearby stowage for up to 117 railcars a $298 million (July 2011 prices) to keep a continuous flow of trains integrated train, bus and pedestrian following events. -

Perth Greater CBD Transport Plan

Department of Transport Perth Greater CBD Transport Plan Phase One: Transport priorities for the Perth Parking Management Area August 2020 Contents Introduction Introduction ............................................................................................................................... Page 3 Perth Greater CBD Transport Plan ............................................................................................ Page 6 Background ................................................................................................................... Page 6 Consultation .................................................................................................................. Page 7 Problem identification and root causes ....................................................................... Page 9 Perth parking ............................................................................................................................. Page 11 Perth Parking Management Act, Regulations and Policy ........................................... Page 11 Perth central city: a better place to live, visit, work, study and invest Perth Parking Management Area and Perth Parking Levy ......................................... Page 12 Easy access and mobility are two vital pillars of a While urban regeneration and cultural Phase One transport priorities for the Perth Parking Management Area............................... Page 13 well-functioning capital city. improvements have continued, the transport network has not always kept pace. -

Encyclopedia of Australian Football Clubs

Full Points Footy ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Volume One by John Devaney Published in Great Britain by Full Points Publications © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2008 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: The Full Points Footy Encyclopedia Of Australian Football Clubs Volume One ISBN 978-0-9556897-0-3 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Clubs. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Introduction For most football devotees, clubs are the lenses through which they view the game, colouring and shaping their perception of it more than all other factors combined. To use another overblown metaphor, clubs are also the essential fabric out of which the rich, variegated tapestry of the game’s history has been woven. -

Mueller Park Address 150 Roberts Road Subiaco Lot Number 9337 Photograph (2014)

City of Subiaco - Heritage Place Record Name Mueller Park Address 150 Roberts Road Subiaco Lot Number 9337 Photograph (2014) Construction 1900 Date Architectural N/A Style Historical Reserve 9337, gazetted in 1904, comprises three distinct areas: Mueller Notes Park, a well-established urban park laid out in 1906-07 and the 1920s, with mature tree plantings, and recent playgrounds; Kitchener Park, a grassed area used for car parking with a small number of mature trees; Subiaco Oval, more recently named Patersons Stadium, a football oval with associated facilities and spectator stands, and Subiaco Oval Gates (Register of Heritage Places, RHP 5478). In the Documentary Evidence the name that pertained at each period is used. An early plan of Subiaco shows Subiaco and Mueller Roads (the latter named in honour of Ferdinand Jakob Heinrich von Mueller (1825-1896), inaugural director of Melbourne Botanic Gardens (1857-73), and Australia’s pre-eminent botanist) with the part of Reserve 591A that later became Mueller Park. During the 1890s gold boom, lack of May 2021 Page 1 City of Subiaco - Heritage Place Record accommodation in the metropolitan area for people heading to the goldfields saw many camping out, raising sanitary concerns. In 1896, men at ‘Subiaco Commonage’ (as the area of Perth Commonage, Reserve 591A, west of Thomas Street, was commonly known) protested against a notice to quit the area and unsuccessfully asked for it to be declared a camping ground. Perth City Council cleared a large number of tents from the area on numerous occasions. In July 1897, the Subiaco Council asked Perth Council to continue Townshend and Hamilton Roads through the Commonage to Subiaco Road, and both these roads and Coghlan Road were made by the early 1900s. -

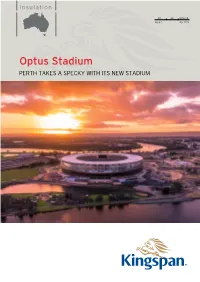

Optus Stadium PERTH TAKES a SPECKY with ITS NEW STADIUM Optus Stadium

Insulation A4 CS AW2314 Issue 1 Apr 2018 Optus Stadium PERTH TAKES A SPECKY WITH ITS NEW STADIUM Optus Stadium Project Summary Project: Optus Stadium integrated well with the expansion of Perth’s public transport Location: Perth , WA system, and gave easier access to the CBD. Whilst the stadium’s Architect: Hassell Architects prime use is to host the AFL, it will also provide an additional Contractors: Cubic Group venue for a number of other sporting events and music concerts. Application: Soffit and Ducting The round stadium consists of tiered seating located above bars and restaurants in the levels below. The unique design by Hassell Description Architects called for a slim profile, thermal solution capable of Subiaco Oval is as much a part of West Australian sporting meeting the limited space allocation while still delivering on the folklore as Dennis Lillee’s chin music, the centimetre perfect AFL high energy efficiency requirements of the project. calls of favourite son Dennis Cometti or the gloriously dangerous With this in mind, the Kingspan technical team, along with the surf breaks of Margaret River. Built in 1908, and primarily known project’s contractors at Cubic Group, designed a customised as the spiritual home of state’s Australian Football League (AFL) installation solution that could be applied to the underside of the teams, the stadium has also played host to such music icons as seating plats. AC/DC, Paul McCartney, U2 and Pearl Jam, and this despite its “We wanted to design an alternate installation system that would famously poor acoustics. be aesthetically pleasing and would not detract from the beauty As the state has come of age, the race has been on to ensure of the design, but retained the thermal performance requirements its capital city’s infrastructure kept pace. -

AFL Fact Sheet February 2017

AFL Fact Sheet February 2017 Optus Stadium - AFL format The multi-purpose Optus Stadium will be a world-class venue capable of hosting a range of events, including Australian Football League (AFL) matches. The commitment to a ‘fans first’ stadium has resulted in an innovative design, ensuring an exceptional event atmosphere and home ground advantage that can only be experienced by being there. Stadium - key AFL features The seating bowl maximises the atmosphere, gives fans and Fremantle Football Club on the north-west. exceptional views and brings them close to the action. Team facilities are over 1,000m2 and includes a change East:west field orientation to replicate alignment of room capable of accommodating 50 people. the MCG and Subiaco Oval. On game days, the West Coast Eagles and Fremantle Field of play dimensions will be 165m along the east- Football Club will be able to utilise two of the largest west axis and 130m on the north-south axis. This is dedicated warm up spaces in Australia, a 60 person slightly shorter than Domain Stadium (Subiaco Oval) coaches briefing room, medical rooms and recovery but aligned with the MCG, which is 160m x 141m. facilities that include hot and cold spas. Using state-of-the-art LED lighting, home team The Coaches Boxes are located on Level 3 of the five colours will be illuminated through the roof to help tiered Stadium, each of which accommodates 30 create a home ground advantage. people. World-class team facilities will be located on the There are four changing rooms for Officials - two male northern side of the Stadium, either side of the Locker and two female. -

As a Player, Umpire, Coach and Spectator – Led Her to Research the History of Women’S Australian Rules Football

Brunette Lenkić is a teacher and freelance journalist whose lifelong interest in sport – as a player, umpire, coach and spectator – led her to research the history of women’s Australian Rules football. She was the driving force behind the ‘Bounce Down!’ exhibition, held at the State Library of Western Australia in 2015, which celebrated 100 years of the women’s game. Brunette lives in Perth, where her daughters play for the Coastal Titans Women’s Football Club. Associate Professor Rob Hess is a sport historian with the College of Sport and Exercise Science, and the Institute of Sport, Exercise and Active Living at Victoria University. He is the former president of the Australian Society for Sports History and the current managing editor of the discipline’s foremost journal, the International Journal of the History of Sport. Rob has a longstanding interest in the history of Australian Rules football, especially the development of the women’s code. Echo Publishing A division of Bonnier Publishing Australia 534 Church Street, Richmond Victoria Australia 3121 www.echopublishing.com.au Copyright © Brunette Lenkić and Rob Hess, 2016 Foreword © Susan Alberti All rights reserved. Echo Publishing thank you for buying an authorised edition of this book. In doing so, you are supporting writers and enabling Echo Publishing to publish more books and foster new talent. Thank you for complying with copyright laws by not using any part of this book without our prior written permission, including reproducing, storing in a retrieval system, transmitting in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or distributing. -

Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Documentation

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES - ASSESSMENT DOCUMENTATION HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 11. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE The criteria adopted by the Heritage Council in November 1996 have been used to determine the cultural heritage significance of the place. PRINCIPAL AUSTRALIAN HISTORIC THEME(S) • 8.1.1 Playing and watching organised sport • 8.9 Commemorating significant events and people HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA THEME(S) • 405 Sport, recreation and entertainment 11. 1 AESTHETIC VALUE* Subiaco Oval Gates is a small scale well executed Inter War Art Deco style building. (Criterion 1.1) Subiaco Oval Gates has a landmark quality at the corner of Haydn Bunton Drive and Roberts Road; and, as the main entrance to Subiaco Oval, the place has been a well-recognised landmark since its construction in 1935. (Criterion 1.2) Subiaco Oval Gates contributes to the aesthetic qualities of the streetscape, providing a contrast in scale and in the materials employed with the nearby two and three tier grandstands. (Criterion 1.3) 11. 2. HISTORIC VALUE Subiaco Oval Gates, the main entrance to Subiaco Oval, is significant as one of a small number of main entrance gates erected in the pre World War Two period to provide formal entry to a sports ground. (Criterion 2.1) Subiaco Oval Gates contributes to an understanding of the cultural history of Western Australia; in particular, the history of Subiaco Oval, and of Australian rules football in this State, having served since its construction in 1935 as the main entrance to the sports ground at which all Western Australian football finals have been played. -

Sydney Olympic Park

THESIS PROJECT SYDNEY OLYMPIC PARK OLYMPIC LEGACY OR BURDEN BY BEN JAMES 2007 AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS SUBMITTED AS A PARTIAL REQUIREMENT FOR THE BACHELOR OF PLANNING DEGREE, UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 2007 ABSTRACT ‘The best Olympic Games ever’ are the words that Olympic organising committees around the world want to hear after they have hosted the Olympic Games. This title can only be held by one host city, and the current holder is Sydney. However, like many host cities in the past, infrastructure built for the Games has not had much of a post-games life. Due to this lack of post-games use, the main Olympic site at Homebush is perceived as a burden on Sydney rather than the unambiguous positive legacy envisaged. Sydney Olympic Park has even been described as a ‘white elephant’. This thesis will look at how the site as a whole has functioned since the Games, with particular reference to underutilisation of the two main stadiums. The potential of the 2002 master plan to inject new uses and vitality into the site is considered. The thesis provides a series of best practice guidelines that could be used by future hosts of similar mega-events to ensure that Games-related infrastructure does not become a burden on the host city. I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would firstly like to thank Peter Williams, who as my thesis advisor provided me with the guidance and assistance that was required for me to complete my thesis. I secondly would like to thank Ellie for her assistance in the reading and formatting of my thesis, as well as her continued support throughout the thesis project. -

Public Accounts Committee

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE REVIEW OF SELECTED WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS Report No. 14 in the 38th Parliament 2011 Published by the Legislative Assembly, Parliament of Western Australia, Perth, December 2011. Printed by the Government Printer, State Law Publisher, Western Australia. Public Accounts Committee Review of Selected Western Australian Infrastructure Projects ISBN: 978-1-921865-30-5 (Series: Western Australia. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committees. Public Accounts Committee. Report 14) 328.365 99-0 Copies available from: State Law Publisher 10 William Street PERTH WA 6000 Telephone: (08) 9426 0000 Facsimile: (08) 9321 7536 Email: [email protected] Copies available on-line: www.parliament.wa.gov.au PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE REVIEW OF SELECTED WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS Report No. 14 Presented by: Hon J.C. Kobelke, MLA Laid on the Table of the Legislative Assembly on 1 December 2011 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Chairman Hon J.C. Kobelke, MLA Member for Balcatta Deputy Chairman Mr J.M. Francis, MLA Member for Jandakot Members Mr A. Krsticevic, MLA Member for Carine Ms R. Saffioti, MLA Member for West Swan Mr C.J. Tallentire, MLA Member for Gosnells COMMITTEE STAFF Principal Research Officer Dr Loraine Abernethie, PhD until 30 June 2011 Mr Mathew Bates, BA (Hons) from 1 July 2011 Research Officer Mr Mathew Bates, BA (Hons) until 30 June 2011 Mr Foreman Foto, BA (Hons), MA from 1 July 2011 COMMITTEE ADDRESS Public Accounts Committee Legislative Assembly Tel: (08) 9222 7494 Parliament House Fax: (08) 9222 7804 Harvest Terrace Email: [email protected] PERTH WA 6000 Website: www.parliament.wa.gov.au/pac - i - PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS COMMITTEE MEMBERS ...............................................................................................................................