The State of the Region: Hampton Roads 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

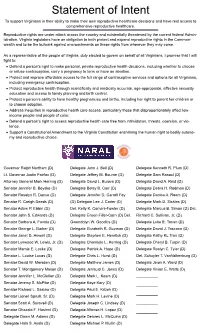

To Support Virginians in Their Ability to Make Their Own Reproductive Healthcare Decisions and Have Real Access to Comprehensive Reproductive Healthcare

Statement of Intent To support Virginians in their ability to make their own reproductive healthcare decisions and have real access to comprehensive reproductive healthcare. Reproductive rights are under attack across the country and existentially threatened by the current federal Admin- istration. Virginia legislators have an obligation to both protect and expand reproductive rights in the Common- wealth and to be the bulwark against encroachments on these rights from wherever they may come. As a representative of the people of Virginia, duly elected to govern on behalf of all Virginians, I promise that I will fight to: • Defend a person's right to make personal, private reproductive health decisions, including whether to choose or refuse contraception, carry a pregnancy to term or have an abortion. • Protect and improve affordable access to the full range of contraceptive services and options for all Virginians, including emergency contraception. • Protect reproductive health through scientifically and medically accurate, age-appropriate, effective sexuality education and access to family planning and birth control. • Protect a person’s ability to have healthy pregnancies and births, including her right to parent her children or to choose adoption. • Address inequities in reproductive health care access, particularly those that disproportionately affect low- income people and people of color. • Defend a person’s right to access reproductive health care free from intimidation, threats, coercion, or vio- lence. • Support a Constitutional Amendment to the Virginia Constitution enshrining the human right to bodily autono- my and reproductive choice. Governor Ralph Northam (D) Delegate John J. Bell (D) Delegate Kenneth R. Plum (D) Lt. Governor Justin Fairfax (D) Delegate Jeffrey M. -

2020 Virginia Capitol Connections

Virginia Capitol Connections 2020 ai157531556721_2020 Lobbyist Directory Ad 12022019 V3.pdf 1 12/2/2019 2:39:32 PM The HamptonLiveUniver Yoursity Life.Proto n Therapy Institute Let UsEasing FightHuman YourMisery Cancer.and Saving Lives You’ve heard the phrases before: as comfortable as possible; • Treatment delivery takes about two minutes or less, with as normal as possible; as effective as possible. At Hampton each appointment being 20 to 30 minutes per day for one to University Proton The“OFrapy In ALLstitute THE(HUPTI), FORMSwe don’t wa OFnt INEQUALITY,nine weeks. you to live a good life considering you have cancer; we want you INJUSTICE IN HEALTH IS THEThe me MOSTn and wome n whose lives were saved by this lifesaving to live a good life, period, and be free of what others define as technology are as passionate about the treatment as those who possible. SHOCKING AND THE MOSTwo INHUMANrk at the facility ea ch and every day. Cancer is killing people at an alBECAUSEarming rate all acr osITs ouOFTENr country. RESULTSDr. William R. Harvey, a true humanitarian, led the efforts of It is now the leading cause of death in 22 states, behind heart HUPTI becoming the world’s largest, free-standing proton disease. Those states are Alaska, ArizoINna ,PHYSICALCalifornia, Colorado DEATH.”, therapy institute which has been treating patients since August Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, 2010. Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, NewREVERENDHampshir DR.e, Ne MARTINw Me LUTHERxico, KING, JR. North Carolina, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West “A s a patient treatment facility as well as a research and education Virginia, and Wisconsin. -

Virginia-Voting-Record.Pdf

2017 | Virginia YOUR LEGISLATORS’ VOTING RECORD ON VOTING RECORD SMALL BUSINESS ISSUES: 2017 EDITION Issues from the 2016 and 2017 General Assembly Sessions: Floor votes by your state legislators on key small business issues during the past two sessions of the Virginia General Assembly are listed inside. Although this Voting Record does not reflect all elements considered by a lawmaker when voting or represent a complete profile of a legislator, it can be a guide in evaluating your legislator’s attitude toward small business. Note that many issues that affect small business are addressed in committees and never make it to a floor vote in the House or Senate. Please thank those legislators who supported small business and continue to work with those whose scores have fallen short. 2016 Legislation 5. Status of Employees of Franchisees (HB 18) – Clarifies in Virginia law that a franchisee or any 1. Direct Primary Care (HB 685 & SB 627) – employee of the franchisee is not an employee of the Clarifies that direct primary care (DPC) agreements franchisor (parent company). A “Yes” vote supports are not insurance policies but medical services and the NFIB position. Passed Senate 27-12; passed provides a framework for patient and consumer pro- House 65-34. Vetoed by governor. tections. These clarifications are for employers who want to offer DPC agreements combined with health 6. Virginia Growth and Opportunity Board insurance as a choice for patients to access afford- and Fund (HB 834 & SB 449) – Establishes the able primary care. A “Yes” vote supports the NFIB Virginia Growth and Opportunity Board to administer position. -

2008 Virginia LCV General Assembly Conservation Scorecard

Our Purpose A Proud Tradition Worth Preserving e Virginia League of Conservation Voters (VALCV) is the non-partisan We Virginians cherish our heritage. We also love our land. We all want clean political action arm of Virginia’s conservation community. VALCV takes its air, clean water, protection of our farmland and forests, and preservation of our franchise from the local, regional and state conservation groups that defi ne our historical landmarks. issues and priorities. Because most of these groups have a 501(c)(3) non-profi t status, and therefore cannot engage in electoral politics, we undertake that eff ort on Too often, however, our government has allowed our history their behalf. to be paved over, our air and waters to become polluted, and our productive land to be wasted by poorly VALCV’s mission is to preserve and enhance the quality of life for all Virginians planned development. by making conservation a top priority with Virginia’s elected offi cials, political candidates and voters. Virginia deserves elected offi cials who are responsive to the people and the needs of e 2008 General Assembly session showed that our legislative priorities extend the environment. beyond the typical environmental areas of concern like air and water quality. Legislation targeting land use and transportation reform as well as the promotion We must urge our elected offi cials to of energy effi ciency came before lawmakers for their consideration this session. accept the challenge to protect Virginia’s Legislation addressing legislative accountability and citizen involvement in natural resources, our abundant wildlife, government was also a top priority. -

2011 Virginia LCV General Assembly Conservation Scorecard

Virginia Generalscorecard Assembly Conservation 2011 Virginia League of Conservation Voters ould you be surprised to learn that challenged and seldom have to address substantive You don’t score points with voters for dropping ninety-one percent of Virginians policy issues. Fewer and fewer voters are engaged the ball on their quality of life! I urge you to take across the state say the environ- in the electoral process and don’t turn out to vote. some time to review the voting records of your Wment is important to them? According to the And the cycle perpetuates itself. representatives. As in other years, many bills latest survey designed by Dr. Quentin Kidd of This is an election year for all 140 House and were killed in subcommittee or failed to receive Christopher Newport University, nearly three- Senate legislative seats in Virginia. At the time of a recorded full committee vote but VALCV staff fifths say environmental protections are generally publication, we do not know if the Virginia line- has carefully selected votes from what was avail- good for the economy. I certainly hope our elected drawing will be approved, but we do know that able. Any vote that appears in our Scorecard grid officials receive copies of this report because it our challenge will be to educate, advocate, and was a bill that we lobbied and on which we com- may convince them that voters do not demon- mobilize on behalf of conservation. Most Virgin- municated our position. ize environmental protections like some special ians do not swing to extremes. They may not be We hope that you will value our Scorecard as an interest groups would have them believe. -

Oppose Mandatory Shift from May to November Elections for Virginia Localities Issue Brief

Oppose Mandatory Shift from May to November Elections for Virginia Localities Senate Email Addresses: Issue Brief Sen. George Barker: District 39 Across Virginia, 44 percent of cities and 57 percent of towns hold Sen. John Bell: District 13 their local elections in May, rather than November. These localities Sen. Jennifer Boysko: District 33 choose to separate their elections from those for state and federal Sen. Amanda Chase: District 11 offices for a variety of reasons – doing so keeps the focus of local Sen. John Cosgrove: District 14 elections on local issues and keeps the cost of campaigning more Sen. Bill DeSteph: District 08 accessible for new candidates. The option to hold elections in May Sen. Creigh Deeds: District 25 gives localities the flexibility they need to best meet the needs of Sen. Siobhan Dunnavant: District 12 their communities. Sen. Adam Ebbin: District 30 Sen. John Edwards: District 21 Sen. Barbara Favola: District 31 SB1157 (Spruill) proposes to mandate that all localities hold their Sen. Emmett Hanger: District 24 elections in November. Sen. Ghazala Hashmi: District 10 Concerns Sen. Janet Howell: District 32 Sen. Jen Kiggans: District 07 The coincidence of local elections with those at the state and Sen. Lynwood Lewis: District 06 federal level inherently raises the level of partisanship of all Sen. Mamie Locke: District 02 elections, regardless of whether candidates are running without any Sen. Louise Lucas: District 18 party affiliation. By the same token, it introduces partisan politics to Sen. David Marsden: District 37 nonpartisan local issues; political parties make little difference Sen. Monty Mason: District 01 when it comes to community projects like paving roads and keeping Sen. -

George Barker D - 39Th District

Senate of Virginia of Senate George Barker D - 39th District Team: Senate Position: Democrat Member Since: 2008 District: Alexandria City (part); Fairfax County (part); Prince William County (part) Hometown: Eldorado, Il Occupation: Consultant Contact Info: 703.303.1426 39 [email protected] George Barker Senate of Virginia of Senate Richard Black R - 13th District Team: Senate Position: Republican Member Since: 2012 District: Loudoun County (part); Prince William County (part) Hometown: Baltimore, MD Occupation: Attorney Contact Info: 703.406.2951 [email protected] 13 Richard Black Senate of Virginia of Senate Jennifer Boysko D - 33rd District Team: Senate Position: Democrat Member Since: 2019 District: Fairfax County (part); Loudon County (part) Hometown: Pine Bluff, AR Occupation: Contact Info: 703.437.0086 [email protected] 33 Jennifer Boysko Senate of Virginia of Senate Charles Carrico R - 40th District Team: Senate Position: Republican Member Since: 2012 District: Bristol City; Grayson County; Lee County; Scott County; Smyth County (part); Washington County; Wise County (part); Wythe County (part) Hometown: Marion, VA Occupation: Senior Trooper, Virginia State Police (retired) Contact Info: 276.236.0098 40 [email protected] Charles Carrico Senate of Virginia of Senate Ben Chafin R - 38th District Team: Senate Position: Republican Member Since: September 18, 2014 District: Bland County; Buchanan County; Dickenson County; Montgomery County (part); Norton City; Pulaski County; Radford -

Virginia Legislative Black Caucus

Black Men Are Diagnosed with Prostate Cancer at Twice the Rate of White Men THIS YEAR: WHAT YOU CAN DO TO LOWER YOUR RISK: • Prostate Cancer is the 2nd leading • Know Your Family History • Don’t just get the test but know your cause of cancer related deaths among stats, know your PSA numbers for the • Exercise 3x/week; eat a diet high in men in the U.S. past three tests and discuss changes ber, fruit, veggies, low in fried food, in your prostate and urinary ow with • 233,000 men will be diagnosed with red meat and processed foods; watch your physician. prostate cancer the scale (as recommended by the • Prostate cancer diagnosis must be American Cancer Society). • 29,480 deaths from prostate cancer separated from treatment. Men • Get annual prostate cancer screenings diagnosed with prostate cancer should African American Men: starting at age 40 (35 if there’s a discuss all available treatment options • Are diagnosed with prostate cancer at family history of prostate cancer) with their doctor. a rate 60% higher than white males We can help you: • PSA testing should be done not on its • Are two times more likely to die from own but should include at minimum a 1. Understand your PSA prostate cancer than white men. Digital Rectal Exam (DRE) 2. Assist You In Obtaining a PSA/ Prostate Cancer Screening “Proton therapy helped me maintain my active lifestyle.” Call the Donald Sherard, Prostate Hampton University 757.251.6800 Cancer Survivor, Chesapeake, Va. Proton Therapy Institute today. hamptonproton.org L EGIS V C B V IRGINIA IRGINIA (VLBC) AUCUS 2017 L C APITOL ACK L C ONNECTIONS ATI V E TRUSTED HEALTH PLANS We are proud to SUPPORT Virginia Legislative black caucus Transition • Education Employment • Benefits Veteran & Family Support Care Centers • Cemeteries Virginia War Memorial www.dvs.virginia.gov www.trustedhp.com (804) 786-0286 Contents African American Legislators since 1967 ..........2 (Provided by Dr. -

1 2020 U.S. Political Engagement Policy and Statement This U.S

2020 U.S. Political Engagement Policy and Statement This U.S. Political Engagement Policy and Statement describes the two types of political engagement by the Company. The first is lobbying, which includes both direct communications with government officials by the Company as well as advocacy by other organizations (i.e., indirect lobbying) that receive financial support from the Company. The second is campaign contributions to candidates for elected office, political parties, political committees, and other organizations that use the contributions for campaign-related purposes. The Company’s policy is to participate in public policymaking by informing government officials about our positions on issues significant to the Company and our customers. The Company conducts this lobbying in the context of existing and proposed laws, legislation, regulations, and policy initiatives, and include, for example, commerce, intellectual property, trade, data privacy, transportation, and web services. Relatedly, the Company constructively and responsibly participates in the U.S. electoral process by making campaign contributions. The goal of the Company’s political engagement is to promote the interests of the Company and our customers, and the Company makes such decisions in accordance with the processes described in this U.S. Political Engagement Policy and Statement, without regard to the personal political preferences of the Company’s directors, officers, or employees. Click here for archives of previous statements. Review and Approval Process The Company’s Vice President of Public Policy reviews and approves each campaign contribution made with Company funds or resources to, or in support of, any candidate, political campaign, political party, political committee, or public official in any country, or to any other organization for campaign-related purposes, to ensure that it is lawful and consistent with the Company’s business objectives and public policy priorities. -

November 2015 Virginia General Assembly Election Update

November 2015 Virginia General Assembly Election Update Prepared by: Williams Mullen Government Relations 2015 Virginia Elections A Statewide Overview On Tuesday, November 3rd , Virginians elected individuals to fill all 140 seats in the Virginia General Assembly. Historically, Virginia has had a limited change in the members of General Assembly as a result of Virginia’s off year election cycle, but partisan redistricting in 2014, a shift in demographics in parts of the state and the retirement of many long serving incumbents, especially in the Senate, created more competitive races in 2015. In the end, despite the spending tens of millions of dollars, Republicans maintained control of the House of Delegates and the Senate, perpetuating the partisan split between the Executive and Legislative branches of government. The House of Delegates Because of their overwhelming existing majority (67 Republican – 33 Democrats), there was no doubt that the Republicans would maintain control of the House of Delegates. Of the 100 seats in the House, there were only eleven seats in which an incumbent was not seeking re-election and in six of those eleven, just a single candidate was running, thus guaranteeing their election. Partisan control of the redistricting process results in the drawing of districts that generally favor most incumbents. Republican control of the last redistricting effort particularly protected Republican incumbents. Democrats won four of the six open seats which were previously held by a Democrat (Delegates Surovell, Krupicka, Preston and Joannou). The two uncontested open seats, previously held by Republicans (Delegates Mark Berg and Ed Scott), were retained by Republicans. Chris Collins, who defeated Delegate Mark Berg in a primary election, will represent House District 29 in the Winchester area and Nick Freitas will succeed Delegate Ed Scott, who did not seek re-election, to represent Culpeper and Orange and Madison counties. -

U.S. Political Contributions and Related Activity Report

U.S. Political Contributions and Related Activity Report January 1 – June 30, 2021 Political Contributions and Related Activity UnitedHealth Group’s mission is to help people live healthier lives and help make the health system work better for everyone. UnitedHealth Group engages in efforts to help shape and inform public policy decisions that ensure all people have access to high-quality, affordable health care. Our participation – including making political contributions – is designed to improve the health care system and positively impact the people we are privileged to serve, our employees and shareholders. We support solutions that build on the strengths of today’s health system and leverage innovative, proven, private sector approaches and successful public-private partnerships. Our priorities include: . Achieving Universal Coverage . Improving Health Care Affordability . Enhancing the Health Care Experience . Achieving Better Health Outcomes Additional public policy information can be found in The Path Forward on UnitedHealth Group’s website. Our activities include the work of educational outreach and promotion, campaign contributions, lobbying, and other related activities. UnitedHealth Group’s Political Action Committee is managed by a long-established governance process that includes a thorough review and approval of each contribution, and public disclosure of contributions in accordance with our Political Contributions Policy. The Board of Directors’ Public Policy Strategies and Responsibility Committee has oversight of political -

Remove Local Redistricting Commission Requirement from HJ615 At-A-Glance Issue Brief

Remove Local Redistricting Commission Requirement from HJ615 At-A-Glance Issue Brief House Legislation: HJ615 (Cole): Constitutional amendment; apportionment, state HJ615 (Cole) and local redistricting commissions Senate Legislation: The House and Senate have each introduced resolutions to establish SJ306 (Barker) bipartisan redistricting commissions. The Senate version, SJ306 (Barker) addresses the State only. The House version, HJ615 (Cole) Issue: would require localities with district-based elections to establish Redistricting commissions for commissions, adhering to the same requirements as that of the state and local elections State. Cities and Towns Potentially Concerns Impacted: 25 HJ615 would introduce partisanship into otherwise nonpartisan local electoral processes and would undermine systems already in place Current GA Committee: that protect the rights of local voters. Most district-based electoral Senate Privileges and Elections systems have been established in response to either Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act or the Department of Justice. This resolution also Committee Members: imposes timelines that could conflict with local election schedules. Chair – Jill Holtzman Vogel [email protected] Janet Howell Potentially Impacted Cities and Towns [email protected] Alexandria* Halifax* Poquoson* Creigh Deeds Berryville* Hillsville* Richmond* [email protected] Blackstone* Hopewell* South Hill* John Edwards Courtland* Lawrenceville* Suffolk* [email protected] Covington* Lynchburg Virginia Beach* Bryce Reeves Emporia Newport News* Warrenton* [email protected] Farmville* Norfolk* Waynesboro* Adam Ebbin Franklin* Petersburg* Winchester [email protected] Fredericksburg* Ben Chafin [email protected] *Indicates locality holds only nonpartisan elections. Bill DeSteph Key Points [email protected] Amanda Chase • The vast majority of cities and towns across Virginia have [email protected] nonpartisan local government.