(Re) Presentation and (Re) Production of Ideology: the Case of Grand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Setting up Horizon 7 for Linux Desktops

Setting Up Horizon 7 for Linux Desktops SEP 2019 VMware Horizon 7 7.10 Setting Up Horizon 7 for Linux Desktops You can find the most up-to-date technical documentation on the VMware website at: https://docs.vmware.com/ If you have comments about this documentation, submit your feedback to [email protected] VMware, Inc. 3401 Hillview Ave. Palo Alto, CA 94304 www.vmware.com © Copyright 2016-2019 VMware, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright and trademark information. VMware, Inc. 2 Contents Setting Up Horizon 7 for Linux Desktops 6 1 Features and System Requirements 7 Features of Horizon Linux Desktops 7 Overview of Configuration Steps for Horizon 7 for Linux Desktops 13 System Requirements For Horizon 7 for Linux 14 Virtual Machine Settings for 2D Graphics 23 Configuring Session Collaboration on Linux Desktops 23 2 Preparing a Linux Virtual Machine for Desktop Deployment 26 Create a Virtual Machine and Install Linux 26 Prepare a Linux Machine for Remote Desktop Deployment 27 Install Dependency Packages for Horizon Agent 29 3 Setting Up Active Directory Integration for Linux Desktops 31 Integrating Linux with Active Directory 31 Use the OpenLDAP Server Pass-Through Authentication 32 Set Up SSSD LDAP Authentication Against the Microsoft Active Directory 32 Use the Winbind Domain Join Solution 32 Configure PowerBroker Identity Services Open (PBISO) Authentication 33 Configure the Samba Offline Domain Join 34 Use the Realmd Join Solution for RHEL 8 36 Setting Up Single Sign-On 37 Setting Up Smart Card Redirection 38 Integrate a RHEL 8 Desktop -

Fedora 14 User Guide

Fedora 14 User Guide Using Fedora 14 for common desktop computing tasks Fedora Documentation Project User Guide Fedora 14 User Guide Using Fedora 14 for common desktop computing tasks Edition 1.0 Author Fedora Documentation Project [email protected] Copyright © 2010 Red Hat, Inc. and others. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https://fedoraproject.org/wiki/ Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. -

Ubuntu® 1.4Inux Bible

Ubuntu® 1.4inux Bible William von Hagen 111c10,ITENNIAL. 18072 @WILEY 2007 •ICIOATENNIAl. Wiley Publishing, Inc. Acknowledgments xxi Introduction xxiii Part 1: Getting Started with Ubuntu Linux Chapter 1: The Ubuntu Linux Project 3 Background 4 Why Use Linux 4 What Is a Linux Distribution? 5 Introducing Ubuntu Linux 6 The Ubuntu Manifesto 7 Ubuntu Linux Release Schedule 8 Ubuntu Update and Maintenance Commitments 9 Ubuntu and the Debian Project 9 Why Choose Ubuntu? 10 Installation Requirements 11 Supported System Types 12 Hardware Requirements 12 Time Requirements 12 Ubuntu CDs 13 Support for Ubuntu Linux 14 Community Support and Information 14 Documentation 17 Commercial Support for Ubuntu Linux 18 Getting More Information About Ubuntu 19 Summary 20 Chapter 2: Installing Ubuntu 21 Getting a 64-bit or PPC Desktop CD 22 Booting the Desktop CD 22 Installing Ubuntu Linux from the Desktop CD 24 Booting Ubuntu Linux 33 Booting Ubuntu Linux an Dual-Boot Systems 33 The First Time You Boot Ubuntu Linux 34 Test-Driving Ubuntu Linux 34 Expioring the Desktop CD's Examples Folder 34 Accessing Your Hard Drive from the Desktop CD 36 Using Desktop CD Persistence 41 Copying Files to Other Machines Over a Network 43 Installing Windows Programs from the Desktop CD 43 Summary 45 ix Contents Chapter 3: Installing Ubuntu on Special-Purpose Systems 47 Overview of Dual-Boot Systems 48 Your Computer's Boot Process 48 Configuring a System for Dual-Booting 49 Repartitioning an Existing Disk 49 Getting a Different Install CD 58 Booting from a Server or Altemate -

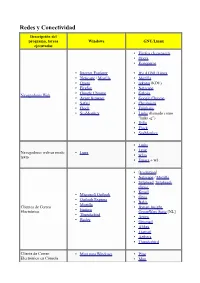

Introducción a Linux Equivalencias Windows En Linux Ivalencias

No has iniciado sesión Discusión Contribuciones Crear una cuenta Acceder Página discusión Leer Editar Ver historial Buscar Introducción a Linux Equivalencias Windows en Linux Portada < Introducción a Linux Categorías de libros Equivalencias Windows en GNU/Linux es una lista de equivalencias, reemplazos y software Cam bios recientes Libro aleatorio análogo a Windows en GNU/Linux y viceversa. Ayuda Contenido [ocultar] Donaciones 1 Algunas diferencias entre los programas para Windows y GNU/Linux Comunidad 2 Redes y Conectividad Café 3 Trabajando con archivos Portal de la comunidad 4 Software de escritorio Subproyectos 5 Multimedia Recetario 5.1 Audio y reproductores de CD Wikichicos 5.2 Gráficos 5.3 Video y otros Imprimir/exportar 6 Ofimática/negocios Crear un libro 7 Juegos Descargar como PDF Versión para im primir 8 Programación y Desarrollo 9 Software para Servidores Herramientas 10 Científicos y Prog s Especiales 11 Otros Cambios relacionados 12 Enlaces externos Subir archivo 12.1 Notas Páginas especiales Enlace permanente Información de la Algunas diferencias entre los programas para Windows y y página Enlace corto GNU/Linux [ editar ] Citar esta página La mayoría de los programas de Windows son hechos con el principio de "Todo en uno" (cada Idiomas desarrollador agrega todo a su producto). De la misma forma, a este principio le llaman el Añadir enlaces "Estilo-Windows". Redes y Conectividad [ editar ] Descripción del programa, Windows GNU/Linux tareas ejecutadas Firefox (Iceweasel) Opera [NL] Internet Explorer Konqueror Netscape / -

Pipenightdreams Osgcal-Doc Mumudvb Mpg123-Alsa Tbb

pipenightdreams osgcal-doc mumudvb mpg123-alsa tbb-examples libgammu4-dbg gcc-4.1-doc snort-rules-default davical cutmp3 libevolution5.0-cil aspell-am python-gobject-doc openoffice.org-l10n-mn libc6-xen xserver-xorg trophy-data t38modem pioneers-console libnb-platform10-java libgtkglext1-ruby libboost-wave1.39-dev drgenius bfbtester libchromexvmcpro1 isdnutils-xtools ubuntuone-client openoffice.org2-math openoffice.org-l10n-lt lsb-cxx-ia32 kdeartwork-emoticons-kde4 wmpuzzle trafshow python-plplot lx-gdb link-monitor-applet libscm-dev liblog-agent-logger-perl libccrtp-doc libclass-throwable-perl kde-i18n-csb jack-jconv hamradio-menus coinor-libvol-doc msx-emulator bitbake nabi language-pack-gnome-zh libpaperg popularity-contest xracer-tools xfont-nexus opendrim-lmp-baseserver libvorbisfile-ruby liblinebreak-doc libgfcui-2.0-0c2a-dbg libblacs-mpi-dev dict-freedict-spa-eng blender-ogrexml aspell-da x11-apps openoffice.org-l10n-lv openoffice.org-l10n-nl pnmtopng libodbcinstq1 libhsqldb-java-doc libmono-addins-gui0.2-cil sg3-utils linux-backports-modules-alsa-2.6.31-19-generic yorick-yeti-gsl python-pymssql plasma-widget-cpuload mcpp gpsim-lcd cl-csv libhtml-clean-perl asterisk-dbg apt-dater-dbg libgnome-mag1-dev language-pack-gnome-yo python-crypto svn-autoreleasedeb sugar-terminal-activity mii-diag maria-doc libplexus-component-api-java-doc libhugs-hgl-bundled libchipcard-libgwenhywfar47-plugins libghc6-random-dev freefem3d ezmlm cakephp-scripts aspell-ar ara-byte not+sparc openoffice.org-l10n-nn linux-backports-modules-karmic-generic-pae -

How to Cheat at Configuring Open Source Security Tools

436_XSS_FM.qxd 4/20/07 1:18 PM Page ii 441_HTC_OS_FM.qxd 4/12/07 1:32 PM Page i Visit us at www.syngress.com Syngress is committed to publishing high-quality books for IT Professionals and deliv- ering those books in media and formats that fit the demands of our customers. We are also committed to extending the utility of the book you purchase via additional mate- rials available from our Web site. SOLUTIONS WEB SITE To register your book, visit www.syngress.com/solutions. Once registered, you can access our [email protected] Web pages. There you may find an assortment of value- added features such as free e-books related to the topic of this book, URLs of related Web sites, FAQs from the book, corrections, and any updates from the author(s). ULTIMATE CDs Our Ultimate CD product line offers our readers budget-conscious compilations of some of our best-selling backlist titles in Adobe PDF form. These CDs are the perfect way to extend your reference library on key topics pertaining to your area of expertise, including Cisco Engineering, Microsoft Windows System Administration, CyberCrime Investigation, Open Source Security, and Firewall Configuration, to name a few. DOWNLOADABLE E-BOOKS For readers who can’t wait for hard copy, we offer most of our titles in downloadable Adobe PDF form. These e-books are often available weeks before hard copies, and are priced affordably. SYNGRESS OUTLET Our outlet store at syngress.com features overstocked, out-of-print, or slightly hurt books at significant savings. SITE LICENSING Syngress has a well-established program for site licensing our e-books onto servers in corporations, educational institutions, and large organizations. -

Setting up Linux Desktops in Horizon

Setting Up Linux Desktops in Horizon VMware Horizon 2103 Setting Up Linux Desktops in Horizon You can find the most up-to-date technical documentation on the VMware website at: https://docs.vmware.com/ VMware, Inc. 3401 Hillview Ave. Palo Alto, CA 94304 www.vmware.com © Copyright 2021 VMware, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright and trademark information. VMware, Inc. 2 Contents Setting Up Linux Desktops in Horizon 6 1 Features and System Requirements 7 Features of Horizon Linux Desktops 7 Overview of Configuration Steps for Setting Up Linux Desktops 13 System Requirements for Horizon Agent for Linux 14 Virtual Machine Settings for 2D Graphics 23 Configuring Session Collaboration on Linux Desktops 23 2 Preparing a Linux Virtual Machine for Desktop Deployment 27 Create a Virtual Machine and Install Linux 27 Update the GNOME Shell Window List Extension on SLED/SLES Virtual Machines 28 Prepare a Linux Machine for Remote Desktop Deployment 29 Install Dependency Packages for Horizon Agent 32 Upgrade the Operating System of a Linux Virtual Machine 33 3 Setting Up Active Directory Integration and User Authentication Features for Linux Desktops 34 Integrating Linux Desktops with Active Directory 34 Use the OpenLDAP Server Pass-Through Authentication 35 Set Up SSSD LDAP Authentication Against the Microsoft Active Directory 35 Use the Winbind Domain Join Solution 36 Configure PowerBroker Identity Services Open (PBISO) Authentication 36 Configure the Samba Offline Domain Join 37 Use the Realmd Join Solution for RHEL/CentOS 8.x 39 Setting Up Single -

Licensing Information User Manual Oracle Solaris 11.3 Last Updated September 2018

Licensing Information User Manual Oracle Solaris 11.3 Last Updated September 2018 Part No: E54836 September 2018 Licensing Information User Manual Oracle Solaris 11.3 Part No: E54836 Copyright © 2018, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation of the programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, shall be subject to license terms and license restrictions applicable to the programs. -

Redes Y Conectividad Descripción Del Programa, Tareas Windows GNU/Linux Ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror

Redes y Conectividad Descripción del programa, tareas Windows GNU/Linux ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror • Internet Explorer • IEs 4 GNU/Linux • Netscape / Mozilla • Mozilla • Opera • rekonq (KDE) • Firefox • Netscape • Google Chrome • Galeón Navegadores Web • Avant Browser • Google Chrome • Safari • Chromium • Flock • Epiphany • SeaMonkey • Links (llamado como "links -g") • Dillo • Flock • SeaMonkey • Links • • Lynx Navegadores web en modo Lynx • texto w3m • Emacs + w3. • [Evolution] • Netscape / Mozilla • Sylpheed , Sylpheed- claws. • Kmail • Microsoft Outlook • Gnus • Outlook Express • Balsa • Mozilla Clientes de Correo • Bynari Insight • Eudora Electrónico GroupWare Suite [NL] • Thunderbird • Arrow • Becky • Gnumail • Althea • Liamail • Aethera • Thunderbird Cliente de Correo • Mutt para Windows • Pine Electrónico en Cónsola • Mutt • Gnus • de , Pine para Windows • Elm. • Xemacs • Liferea • Knode. • Pan • Xnews , Outlook, • NewsReader Lector de noticias Netscape / Mozilla • Netscape / Mozilla. • Sylpheed / Sylpheed- claws • MultiGet • Orbit Downloader • Downloader para X. • MetaProducts Download • Caitoo (former Kget). Express • Prozilla . • Flashget • wxDownloadFast . • Go!zilla • Kget (KDE). Gestor de Descargas • Reget • Wget (console, standard). • Getright GUI: Kmago, QTget, • Wget para Windows Xget, ... • Download Accelerator Plus • Aria. • Axel. • Httrack. • WWW Offline Explorer. • Wget (consola, estándar). GUI: Kmago, QTget, Extractor de Sitios Web Teleport Pro, Webripper. Xget, ... • Downloader para X. • -

Mastering EOS Release 1.0

Mastering EOS Release 1.0 Sean Fisk and Ira Woodring May 12, 2015 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Physical Access (Keycards) ....................................... 3 1.2 Computer Access (Credentials) ..................................... 3 2 Rules and Procedures 5 2.1 Disk Space ................................................ 5 2.2 Copyrighted Material ........................................... 5 2.3 Food and Drink .............................................. 6 2.4 Overnight Parking ............................................ 6 2.5 Living in the Lab ............................................. 6 2.6 Malicious Activity ............................................ 6 2.7 Games .................................................. 6 3 Using the Command Line 7 3.1 Command-Line Basics .......................................... 7 3.2 Available Shells ............................................. 7 3.3 Interactive Shell Use ........................................... 10 3.4 Shell Scripting .............................................. 24 4 Remote Access (SSH/VNC) 27 4.1 Inter-EOS SSH .............................................. 27 4.2 Microsoft Windows ........................................... 28 4.3 Mac OS X ................................................ 36 4.4 GNU/Linux ................................................ 49 5 User-level Software Installation 65 5.1 The Standard Hierarchy ......................................... 65 5.2 Manual Installation ............................................ 66 5.3 Linuxbrew ............................................... -

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Migration Planning Guide

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Migration Planning Guide Key differences between Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 and Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Last Updated: 2021-09-21 Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Migration Planning Guide Key differences between Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 and Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Legal Notice Copyright © 2021 Red Hat, Inc. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ . In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, the Red Hat logo, JBoss, OpenShift, Fedora, the Infinity logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Linux ® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java ® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS ® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL ® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. Node.js ® is an official trademark of Joyent. -

Opengear User Manual

User Manual ACM5000 & ACM5500 Management Gateways IM4200 Infrastructure Managers CM4100 Console Servers SD4000 Secure Device Servers Rev: 4.8 th April 9 2013 Data Center and Remote Site Management - User Manual 1 Safety Please take care to follow the safety precautions below when installing and operating the console server: - Do not remove the metal covers. There are no operator serviceable components inside. Opening or removing the cover may expose you to dangerous voltage which may cause fire or electric shock. Refer all service to Opengear qualified personnel - To avoid electric shock the power cord protective grounding conductor must be connected through to ground. - Always pull on the plug, not the cable, when disconnecting the power cord from the socket. Do not connect or disconnect the console server during an electrical storm. Also it is recommended you use a surge suppressor or UPS to protect the equipment from transients. FCC Warning Statement This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC rules. Operation of this device is subject to the following conditions: (1) This device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference that may cause undesired operation. Proper back-up systems and necessary safety devices should be utilized to protect against injury, death or property damage due to system failure. Such protection is the responsibility of the user. This console server device is not approved for use as a life-support or medical system. Any changes or modifications made to this console server device without the explicit approval or consent of Opengear will void Opengear of any liability or responsibility of injury or loss caused by any malfunction.