The Genesis of the Declaration: a Fresh Examination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote for None Or One United States Senator

Nueces County General Nueces County, Texas Official Results Election Registered Voters Nueces County, General Election 128098 of 212048 = 60.41% November 3, 2020 General Election Precincts Reporting 0 of 127 = 0.00% 11/3/2020 Run Time 2:38 PM Run Date 11/17/2020 Page 1 President and Vice President - Vote for None or One Choice Party Absentee Voting Early Voting Election Day Voting Total Donald J. Trump/Michael R. Pence REP 5,006 31.54% 50,822 53.26% 8,789 54.83% 64,617 50.75% Joseph R. Biden/Kamala D. Harris DEM 10,728 67.59% 43,352 45.43% 6,845 42.70% 60,925 47.85% Jo Jorgensen/Jeremy "Spike" Cohen LIB 114 0.72% 988 1.04% 302 1.88% 1,404 1.10% Howie Hawkins/Angela Walker GRN 17 0.11% 258 0.27% 93 0.58% 368 0.29% Brian Carroll/Amar Patel (W) 6 0.04% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 6 0.00% Gloria La Riva/Leonard Peltier (W) 1 0.01% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 1 0.00% Tom Hoefling/Andy Prior (W) 1 0.01% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 1 0.00% Cast Votes: 15,873 100.00% 95,420 100.00% 16,029 100.00% 127,322 100.00% Undervotes: 133 512 120 765 Overvotes: 11 0 0 11 United States Senator - Vote for None or One Choice Party Absentee Voting Early Voting Election Day Voting Total John Cornyn REP 5,429 34.73% 50,845 54.03% 8,284 53.18% 64,558 51.52% Mary "MJ" Hegar DEM 9,991 63.91% 40,745 43.30% 6,444 41.37% 57,180 45.63% Kerry Douglas McKennon LIB 155 0.99% 1,802 1.91% 607 3.90% 2,564 2.05% David B. -

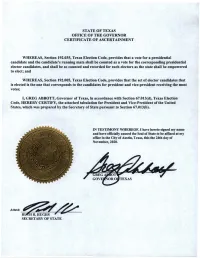

Texas Certificate of Ascertainment 2020

STATE OF TEXAS OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR CERTIFICATE OF ASCERTAINMENT WHEREAS, Section 192.035, Texas Election Code, provides that a vote for a presidential candidate and the candidate's running mate shall be counted as a vote for the corresponding presidential elector candidates, and shall be so counted and recorded for such electors as the state shall be empowered to elect; and WHEREAS, Section 192.005, Texas Election Code, provides that the set of elector candidates that is elected is the one that corresponds to the candidates for president and vice-president receiving the most votes; I, GREG ABBOTT, Governor of Texas, in accordance with Section 67.013(d), Texas Election Code, HEREBY CERTIFY, the attached tabulation for President and Vice-President of the United States, which was prepared by the Secretary of State pursuant to Section 67.013(b). IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF, I have hereto signed my name and have officially caused the Seal of State to be affixed at my office in the City of Austin, Texas, this the 24th day of November, 2020. Attest:~ SECRETARY~Hfrn:HS~~ OF STATE CANDIDATES/PARTY VOTES RECEIVED REPUBLICAN PARTY Donald J. Trump / Michael R. Pence 5,890,347 DEMOCRATIC PARTY Joseph R. Biden / Kamala D. Harris 5,259,126 LIBERTARIAN PARTY Jo Jorgensen I Jeremy "Spike" Cohen 126,243 GREEN PARTY Howie Hawkins / Angela Walker 33,396 DECLARED WRITE-IN CANDIDATES President R. Boddie / Eric C. Stoneham 2,012 Brian Carroll / Amar Patel 2,785 Todd Cella / Tim Cella 205 Jesse Cuellar I Jimmy Monreal 49 Tom Hoefling / Andy Prior 337 Gloria La Riva / Leonard Peltier 350 Abram Loeb / Jennifer Jairala 36 Robert Morrow I Anne Beckett 56 Kasey Wells / Rachel Wells 114 ELECTORS FOR REPUBLICAN PARTY 1. -

OFFICIAL 2020 PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS General Election Date: 11/03/2020 OFFICIAL 2016 PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS

OFFICIAL 2020 PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS General Election Date: 11/03/2020 OFFICIAL 2016 PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS General Election Date: 11/08/2016 Source: State Elections Offices* SOURCE: State Elections Offices* STATE ELECTORAL ELECTORAL VOTES CAST FOR ELECTORAL VOTES CAST FOR VOTES JOSEPH R. BIDEN (D) DONALD J. TRUMP (R) AL 9 9 AK 3 3 AZ 11 11 AR 6 6 CA 55 55 CO 9 9 CT 7 7 DE 3 3 DC 3 3 FL 29 29 GA 16 16 HI 4 4 ID 4 4 IL 20 20 IN 11 11 IA 6 6 KS 6 6 KY 8 8 LA 8 8 ME 4 3 1 MD 10 10 MA 11 11 MI 16 16 MN 10 10 MS 6 6 MO 10 10 MT 3 3 NE 5 1 4 NV 6 6 NH 4 4 NJ 14 14 NM 5 5 NY 29 29 NC 15 15 ND 3 3 OH 18 18 OK 7 7 OR 7 7 PA 20 20 RI 4 4 SC 9 9 SD 3 3 TN 11 11 TX 38 38 UT 6 6 VT 3 3 VA 13 13 WA 12 12 WV 5 5 WI 10 10 WY 3 3 Total: 538 306 232 Total Electoral Votes Needed to Win = 270 - Page 1 of 12 - OFFICIAL 2020 PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS General Election Date: 11/03/2020 SOURCE: State Elections Offices* STATE BIDEN BLANKENSHIP BODDIE CARROLL CHARLES AL 849,624 AK 153,778 1,127 AZ 1,672,143 13 AR 423,932 2,108 1,713 CA 11,110,250 2,605 559 CO 1,804,352 5,061 2,515 2,011 CT 1,080,831 219 11 DE 296,268 1 87 8 DC 317,323 FL 5,297,045 3,902 854 GA 2,473,633 61 8 701 65 HI 366,130 931 ID 287,021 1,886 163 IL 3,471,915 18 9,548 75 IN 1,242,416 895 IA 759,061 1,707 KS 570,323 KY 772,474 7 408 43 LA 856,034 860 1,125 2,497 ME 435,072 MD 1,985,023 4 795 30 MA 2,382,202 MI 2,804,040 7,235 963 MN 1,717,077 75 1,037 112 MS 539,398 1,279 1,161 MO 1,253,014 3,919 664 MT 244,786 23 NE 374,583 NV 703,486 3,138 NH 424,937 -

June 7-20, 2018 • Norwood News

3URXGO\6HUYLQJ%URQ[&RPPXQLWLHV6LQFHProudly Serving Bronx Communities Since 1988 FREE 3URXGO\6HUYLQJ%URQ[&RPPXQLWLHV6LQFHFREE ORWOODQ EWSQ NVol. 27, No. 8 PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION N April 17–30, 2014 Vol 31, No 12 • PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION COR P ORATION • JUNE 7-20, 2018 ORWOODQ EWSQ NVol. 27, No. 8 PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION N April 17–30, 2014 FREE INQUIRING PHOTOGRAPHER: SEE PICTURES: NAT’L ANTHEM CONTROVERSY | PG. 4 AMAZING BRONX FLOTILLA | PG. 9 BREAKING GROUND Another Norwood Killing ON SKATE PARK pg 3 Officials usher in construction of skate park at Oval Park, 15 years in the making Remembering Veterans at Woodlawn pg 4 Mind to Mind, Heart to Heart pg 6 Photo by Jose A. Giralt BREAKING GROUND ON the new skate part on June 5 in Norwood’s Williamsbridge Oval Park include (l-r) skateboarder Eusebio Baez, Bronx Parks Commissioner Iris Rodriguez, Friends of Williamsbridge Oval Vice President Doug Condit, NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver, Councilman Andrew Cohen, Community Board 7 District Manger Ischia Bravo, and skateboarder Awnimosa. By MARTIKA ORNELLA struction on something we’ve breaking on June 5 to usher bringing the project’s total and JOSE A. GIRALT been waiting for for a very in construction of the long- cost at just under $1 million. “Today is a big day for long time: A skate park right awaited skate park. Queens-based LC Construc- the Norwood community,” here in Williamsbridge Oval Councilman Andrew Co- tion will build the skate park, said city Parks Department [Park].” hen, representing Norwood, which is set to open next Feb- Commissioner Mitchell Sil- Together, with a number funded $750,000 in capital ruary. -

214: May 2016 a Free Paper for Free People

#214: MAy 2016 The IndypendenTyears A FRee pApeR FOR FRee peOpLe VeRIZOn’S STRIKInG WORKeRS, p4 pIpeLIneS VS. pLAneT, p14 ReMeMBeRInG pRInCe, p18 BATTLe OF ny phOTO eSSAy, p2 MIChAeL RATneR, p3 CUny STRIKe VOTe, p5 nypd, nOT TO The ReSCUe, p6 eLeCTIOn BOARd COnFROnTed, p7 My BeRnIe JOURney, p8 GOOdMAn & SOLnIT, p16 The LIBeRAL COCOOn, p17 WhAT’S neXT? TWO OCCUpy-InSpIRed ORGAnIZeRS WhO heLped LAUnCh The BeRnIe SAndeRS MOVeMenT LOOK TO The FUTURe. p10 DAVID HOLLENBACH insiDe 2 BACK Vote BerNie or Bust? soMe deLeGates two-party systeM MEDIA apriL 19 are More super iN sHaMBLes, Lesser BreaK tHe MaCHiNe tHaN otHers eviLs oN tHe ropes THE BATTLE OF NEW YORK The IndypendenT tuesDAY, APril 19, 2016 #BattleofnewYork #notMeus Cover art: Nona Hildebrand, w/Zak Greene & Jb. Photo: Tod Seelie Tod Photo: Jb. & Greene w/Zak Nona Hildebrand, art: Cover CoroNatioN or eLeCtioN YOU DECIDE! Five years ago we learned to occupy hierarchy of old. When Clinton says things tion newspaper before the primary, in just Wall Street, to speak less to power and won’t get better, that we won’t get health- the past few days. Operation Battle of New more truth to each other. When Eric care or that war is permanent — even with York can’t replace “the media.” But we can, Garner cried out, “I can’t breathe” in THE INDYPENDENT, INC. his final moments — we knew exactly no declared enemies — there is no reason in this moment, see each other. what he meant. With the entire political, in the world to accept this. -

Feb 2021 Newsletter

Amnesty International UK NAMCAR Newsletter Feb 2021 North America and the Caribbean Canada, USA, Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic and English Speaking Caribbean Hello All It’s been quite a year… As the COVID-19 pandemic tears across the world we are all worried about the future. In countries where the virus has hit many have already lost loved ones. Elsewhere people are bracing them- selves for the spread of the virus, wondering how stretched healthcare systems can possibly cope. Even for those who haven’t yet been directly affected, COVID-19 is disrupting lives in unimaginable ways. Whether you are working from home, out of work, self-isolating or caring for others, these are lonely and uncertain times. Life may feel like it’s on hold right now - but the fight for human rights never stops. With great regret, I have to resign from my role as Country Coordinator effective from the end of January. Family, outside work commitments and the impact of the pandemic have proved too much. I will, of course, continue to take action and campaign alongside you all. It has been an honour working alongside such dedicated and able campaigners as Sue and Lise. If you are interested in applying deadline is 31st Jan https://www.amnesty.org.uk/jobs/country-coordinator-caribbean-states- excluding-cuba Keep Fighting Angus 2 USA The Year 2020 for North America COVID-19 has been dominating the year with its consequence in terms of Human Rights. The pandemic has laid bare systemic disparities that have long undermined our human rights, in- cluding those to life and health, to work, to social security, and to be free from discrimination. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

Our History Is the Future: Mni Wiconi and the Struggle for Native Liberation Nick Estes University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-15-2017 Our History is the Future: Mni Wiconi and the Struggle for Native Liberation Nick Estes University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Estes, Nick. "Our History is the Future: Mni Wiconi and the Struggle for Native Liberation." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/59 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nick Estes Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jennifer Nez Denetdale, Chairperson Dr. David Correia Dr. Alyosha Goldstein Dr. Christina Heatherton i OUR HISTORY IS THE FUTURE: MNI WICONI AND THE STRUGGLE FOR NATIVE LIBERATION BY NICK ESTES B.A., History, University of South Dakota, 2008 M.A., History, University of South Dakota, 2013 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy PhD, American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2017 ii DEDICATION For the Water Protectors, the Black Snake Killaz, the Land Defenders, the Treaty Councils, the Old Ones, the Good People of the Earth. -

The American Militia Phenomenon: a Psychological

THE AMERICAN MILITIA PHENOMENON: A PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILE OF MILITANT THEOCRACIES ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Political Science ____________ by © Theodore C. Allen 2009 Summer 2009 PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights ...................................................................................................... iii Abstract....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1 II. Literature Review of the Modern Militia Phenomenon ........................... 11 Government Sources .................................................................... 11 Historical and Scholarly Works.................................................... 13 Popular Media .............................................................................. 18 III. The History of the Militia in America...................................................... 23 The Nexus Between Religion and Race ....................................... 28 Jefferson’s Wall of Separation ..................................................... 31 Revolution and the Church.......................................................... -

Summary Results Report 2020 General Election November 3, 2020

Summary Results Report UNOFFICIAL RESULTS 2020 General Election Precinct Report November 3, 2020 Henderson 1A President / Vice-President Vote For 1 Early Voting Election TOTAL VOTE % Early Voting by Mail Day REP Donald J. Trump / Michael R. Pence 1,105 83.71% 51 840 214 DEM Joseph R. Biden / Kamala D. Harris 197 14.92% 30 150 17 LIB Jo Jorgensen / Jeremy "Spike" Cohen 8 0.61% 0 6 2 GRN Howie Hawkins / Angela Walker 2 0.15% 1 0 1 Write-In Totals 1 0.08% 0 1 0 Write-In: Uncertified Write-Ins 1 0.08% 0 1 0 Write-In: Abram Loeb/Jennifer Jairala 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Write-In: Robert Morrow/Anne Beckett 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Write-In: Kasey Weells/Rachel Wells 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Write-In: President R. Boddie/Eric C. 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Stoneham Write-In: Brian Carroll/Amar Patel 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Write-In: Todd Cella/Tim Cella 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Write-In: Jesse Cuellar/Jimmy Monreal 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Write-In: Tom Hoefling/Andy Prior 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Write-In: Gloria La Riva/Leonard Peltier 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Not Assigned 0 0.00% 0 0 0 Overvotes 4 0.30% 4 0 0 Undervotes 3 0.23% 0 3 0 Precinct Report - 11/04/2020 11:24 AM Page 1 of 254 Report generated with Electionware Copyright © 2007-2018 Summary Results Report UNOFFICIAL RESULTS 2020 General Election Precinct Report November 3, 2020 Henderson 1A US Senator Vote For 1 Early Voting Election TOTAL VOTE % Early Voting by Mail Day REP John Cornyn 1,076 81.52% 50 826 200 DEM Mary "MJ" Hegar 197 14.92% 27 149 21 LIB Kerry Douglas McKennon 24 1.82% 4 14 6 GRN David B. -

Criminalization of Human Rights Defenders of Indigenous Peoples and the Extractive Industry in the United States, IACHR 172Nd Period of Sessions (May 9

1201 E. Speedway P.O. Box 210176 Tucson, Arizona 85721 ~ 520 - 626- 8223 Report to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Prepared by the University of Arizona Rogers College of Law, Criminalization of Human Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy Program on behalf of the Water Protector Legal Collective Rights Defenders of Indigenous Peoples Resisting Extractive Industries in the United States Introduction 1. Peaceful demonstrations are a catalyst for the advancement of human rights. Yet around the world governments are criminalizing dissent and suppressing public protest, often as a means to protect corporate interests. In this context, indigenous peoples increasingly find themselves as the subjects of arrests, criminal prosecution and police violence when defending the lands they rely upon for their existence and survival from resource extraction by industries who are operating without the free prior and informed consent of the affected communities.1 2. This report is submitted to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in conjunction with a thematic hearing held during the 172nd period of sessions.2 At the hearing, Commissioners heard directly from those involved in the indigenous-led resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) at Standing Rock, North Dakota.3 This report addresses the criminalization and suppression of protest by indigenous human rights defenders and their allies by United States (U.S.) federal, state and local governments, working hand-in-hand with private security forces, specifically in relation to the construction and operation of DAPL by Energy Transfer Partners and Dakota Access, LLC (Dakota Access) and the connected Bayou Bridge Pipeline (collectively the “Bakken Pipeline”). -

Salmon Power a Historic Legal Victory Could Give Alaska Tribes More Control Over Their Fish, Wildlife and Homelands by Krista Langlois July 25, 2016 | $5 | Vol

LAND-TRANSFER BACKERS | OIL AND GAS AUCTIONS GO ONLINE | JUSTICE FOR LEONARD PELTIER High Country ForN people whoews care about the West Salmon Power A historic legal victory could give Alaska tribes more control over their fish, wildlife and homelands By Krista Langlois July 25, 2016 | $5 | Vol. 48 No. 12 | www.hcn.org 12 48 No. | $5 Vol. 25, 2016 July CONTENTS FROM OUR WEBSITE: HCN.ORG Editor’s note On sovereignty and FBI nabs suspected BLM bomber On June 22, FBI agents arrested William Keebler, a Utah man, for allegedly subjugation orchestrating an attack on a Bureau of Land Management cabin in on Mount Trumbull northwest Arizona. The night before, the Patriots Defense In the 1970s, the Pacific Force militia planted a bomb at the facility with the intention of blowing Northwest was at war over it apart. Undercover agents apparently thwarted the attack by providing fishing. Tribal fishermen a faulty bomb, which failed to explode. Keebler, who leads the group, allegedly orchestrated the failed attack in response to what he views as insisted on their right to government overreach and the mismanagement of natural resources. Court catch more salmon, inspiring documents state that Keebler intended to blow up government vehicles a lawsuit against the state and buildings, not people, though he also wanted to create a second of Washington that 14 tribes eventually joined. In bomb that might be “used against law enforcement if they got stopped 1974, a white U.S. district court judge decided in while driving.” This recent bombing plot is part of a long history of violent threats toward federal-lands agency employees that stems from deep- their favor, granting them rights to half the salmon rooted disputes over public-lands management.