MED00006.Pdf (537.3Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astonishing X-Men by Joss Whedon and John Cassaday Ultimate Collection 1St Edition Download Free

ASTONISHING X-MEN BY JOSS WHEDON AND JOHN CASSADAY ULTIMATE COLLECTION 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Joss Whedon | 9780785161943 | | | | | Astonishing X-Men: Ultimate Collection, Volume 1 Then it's a big ass, hybrid Sentinel. No big surprise that there's great dialogue and great use of an ensemble cast but I am really blown away by the emotion here. Emma Frost is shown to be both commanding but still emotional, and Wolverine:. Indeed, even the continuity of having one artist gives this run a different feel. Betsy told the team that her attacker was the Shadow King and he's attacking psychics in an effort to return from the astral plane. This review addresses all 24 issues by Whedon and Cassaday. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. However, Machinesmith had been manipulating her into trying to break him loose while trying to take over her body. Bleeding Cool. Only one person has been retrieved from the station, but he leaves Brand for dead. Be the first to ask a question about Astonishing X-Men 1. An unforgettable read. And it should be read by both X-Men fans and comic fans alike. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. How are ratings calculated? While the two sisters reach reconciliation, their father takes advantage of their engagement and shoots Hatchi. You know the saying: There's no time like the present Get A Copy. The Danger Room AI gone sentient and rogue? In that case, we can't Wolverine was apparently murdered by Death in the final pages of the series, but it was later revealed that "Death" was actually a mind controlled Wolverineand that the "Wolverine" who was killed was an imposter, a shapeshifting Skrull. -

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012

26901 Agoura Road, Suite 150, Calabasas Hills, CA 91301 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012 LOT ITEM PRICE 4 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $275 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE”. 5 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $200 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE” FIGHTING BAD GUYS. 6 X-MEN “PHOENIX SAGA (PART 3) CRY OF THE BANSHEE”, ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL $100 AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “ERIK THE REDD”. 8 X-MEN OVERSIZED ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $150 “GAMBIT”, “ROGUE”, “PROFESSOR X” & “JUBILEE”. 9 X-MEN “WEAPON X, LIES, AND VIDEOTAPE”, (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND $225 BACKGROUND FEATURING “WOLVERINE” IN WEAPON X CHAMBER. 16 X-MEN ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “BEAST”. $100 17 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “NASTY BOYS”, $100 “SLAB” & “HAIRBAG”. 21 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”. $100 23 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND (2) SKETCHES FEATURING CYCLOPS’ $125 VISION OF JEAN GREY AS “PHOENIX”. 24 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $150 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 25 X-MEN (9) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND PAN BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $175 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 27 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”, $100 “ROGUE” AND “DARKSTAR” FLYING. 31 X-MEN THE ANIMATED SERIES, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $100 FEATURING “PROFESSOR X” AND “2 SENTINELS”. 35 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION PAN CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $100 “WOLVERINE”, “ROGUE” AND “NIGHTCRAWLER”. -

X-Men: Apocalypse' Succeeds Thanks to Its Rich Characters

http://www.ocolly.com/entertainment_desk/x-men-apocalypse-succeeds-thanks-to-its-rich- characters/article_ffbc145a-251d-11e6-9b66-f38ca28933de.html 'X-Men: Apocalypse' succeeds thanks to its rich characters Brandon Schmitz, Entertainment Reporter, @SchmitzReviews May 28, 2016 20th Century FOX It's amazing to think that Fox's "X-Men" saga has endured for more than a decade and a half with only a couple of stumbles. From the genre- revitalizing first film to the exceptionally intimate "Days of Future Past," the series has definitely made its mark on the blockbuster landscape. With "Apocalypse," director Bryan Singer returns for his fourth time at the helm. Similarly to his previous outing, this movie is loosely based on one of the superhero team's most popular comic book storylines. Ten years have passed since Charles Xavier (James McAvoy) and friends averted the rise of the Sentinels. However, altering the course of the "X- Men" continuity has merely replaced one disaster with another. The world's first mutant, Apocalypse (Oscar Isaac), was worshipped as a god around the dawn of civilization. Thanks to abilities he has taken from other mutants, he is virtually immortal. Following thousands of years of slumber, Apocalypse wakes to find a world ruled by people who he feels are weak. Namely, humans. Dissatisfied with earth's warring nations, the near-all-powerful mutant sets out to cleanse the world with his four "horsemen." In the wake of this new threat, Mystique (Jennifer Lawrence) must lead a young X-Men team comprised of familiar faces such as Cyclops (Tye Sheridan) and Jean Grey (Sophie Turner). -

X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom Free

FREE X-MEN EPIC COLLECTION: CHILDREN OF THE ATOM PDF Stan Lee,Jack Kirby | 520 pages | 31 Dec 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785189046 | English | New York, United States X-Men Epic Collection: Children Of The Atom - Comics by comiXology Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. X-Men Epic Collection Vol. Jack Kirby. Now, in this massive Epic Collection, you can feast your eyes as Stan, Jack and co. You'll experience the beginning of Professor X's teen team and their mission for peace and brotherhood between man Billed as "The Strangest Super-Heroes of All! You'll experience the beginning of Professor X's teen team and their mission for peace and brotherhood between man and mutant; their first battle with arch-foe Magneto; the dynamic debuts of Juggernaut, the Sentinels, Quicksilver, the Scarlet X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom and X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Jun 27, Sean Gibson rated it really liked it. And, I love me X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom Stan Lee—the guy is one of my real-life heroes, and Spider-Man is my all- time favorite superhero. -

Avengers and Its Applicability in the Swedish EFL-Classroom

Master’s Thesis Avenging the Anthropocene Green philosophy of heroes and villains in the motion picture tetralogy The Avengers and its applicability in the Swedish EFL-classroom Author: Jens Vang Supervisor: Anne Holm Examiner: Anna Thyberg Date: Spring 2019 Subject: English Level: Advanced Course code: 4ENÄ2E 2 Abstract This essay investigates the ecological values present in antagonists and protagonists in the narrative revolving the Avengers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The analysis concludes that biocentric ideals primarily are embodied by the main antagonist of the film series, whereas the protagonists mainly represent anthropocentric perspectives. Since there is a continuum between these two ideals some variations were found within the characters themselves, but philosophical conflicts related to the environment were also found within the group of the Avengers. Excerpts from the films of the study can thus be used to discuss and highlight complex ecological issues within the EFL-classroom. Keywords Ecocriticism, anthropocentrism, biocentrism, ecology, environmentalism, film, EFL, upper secondary school, Avengers, Marvel Cinematic Universe Thanks Throughout my studies at the Linneaus University of Vaxjo I have become acquainted with an incalculable number of teachers and peers whom I sincerely wish to thank gratefully. However, there are three individuals especially vital for me finally concluding my studies: My dear mother; my highly supportive girlfriend, Jenniefer; and my beloved daughter, Evie. i Vang ii Contents 1 Introduction -

Azazel Historically, the Word Azazel Is an Idea and Rarely an Incarnate Demon

Azazel Historically, the word azazel is an idea and rarely an incarnate demon. Figure 1 Possible sigil of Azazel. Modern writings use the sigil for the planet Saturn as well. Vayikra (Leviticus) The earliest known mention of the word Azazel in Jewish texts appears in the late seventh century B.C. which is the third of the five books of the Torah. To modern American ( וַיִּקְרָ א ) book called the Vayikra Christians, this books is Leviticus because of its discussion of the Levites. In Leviticus 16, two goats are placed before the temple for selection in an offering. A lot is cast. One Goat is then sacrificed to Yahweh and the other goats is said to outwardly bear all the sends of those making the sacrifice. The text The general translation .( לַעֲזָאזֵל ) specifically says one goat was chosen for Yahweh and the for Az azel of the words is “absolute removal.” Another set of Hebrew scholars translate Azazel in old Hebrew translates as "az" (strong/rough) and "el" (strong/God). The azazel goat, often called the scapegoat then is taken away. A number of scholars have concluded that “azazel” refers to a series of mountains near Jerusalem with steep cliffs. Fragmentary records suggest that bizarre Yahweh ritual was carried out on the goat. According to research, a red rope was tied to the goat and to an altar next to jagged cliff. The goat is pushed over the cliff’s edge and torn to pieces by the cliff walls as it falls. The bottom of the cliff was a desert that was considered the realm of the “se'irim” class of demons. -

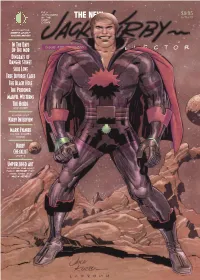

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

Fully $9.95 Authorized THE NEW By The In The US Kirby Estate SPOTLIGHTING KIRBY’S LEAST- KNOWN WORK! In The Days Of The Mob ISSUE #32, JULY 2001 Collector Dingbats of Danger Street Soul Love True Divorce Cases The Black Hole The Prisoner Marvel Westerns The Horde and more! A Long-Lost Kirby Interview Mark Evanier on the Fourth World Kirby Checklist UPDATE Unpublished Art including published pages Before They Were Inked, And Much More!! Contents OPENING SHOT . .2 THE NEW (to those who say “We don’t need no stinkin’ unknown Kirby work”, the editor politely says “Phooey”) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (the story behind the somewhat Glen Campbell-looking fellow on our covers) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier answers a reader’s ISSUE #32, JULY 2001 Collector Frequently Asked Questions about the Fourth World) ANIMATED GESTURES . .11 (Eric Nolen-Weathington begins his ongoing crusade to make sense of some of the animation art Kirby drew) IN HIS OWN WORDS . .12 (Kirby speaks in this long-lost interview from France—oui!) CREDIT CHECK . .22 (Kirby sets a new record, as we present the long-awaited update to the Kirby Checklist, courtesy of Richard Kolkman) GALLERY . .32 (some of Kirby’s least-known and/or never-seen art gets its day in the sun) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .44 (Adam McGovern takes another swat at those pesky Kirby homages that are swarming around his mailbox) INTERNATIONALITIES . .46 (this issue’s look at Jack’s international influence finds Jean-Marie Arnon owes the King a huge debt) TRIVIA . -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee

NOTES CARDS WITH LINKS TO PICS (BLUE), FOLLOWED BY THOSE LISTED IN BOLD ARE HIGHEST PRIORITY I NEED MULTIPLES OF EVERY CARD LISTED, AS WELL AS PACKS, DECKS, UNCUT SHEETS, AND ENTIRE COLLECTIONS Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee - Character 5 Multipower Power Card Black Cat - Femme Fatale 8 Anypower Card Cyclops - Remove Visor 6 Anypower + 2 Basic Universe (Power Blast - Spawn) Ghost Rider - Hell on Wheels Any Character's - Flight, Massive Muscles, & Super Speed Human Torch - Character Artifacts (Linkstone, Myrlu Symbiote, The Witchblade) Iceman - Character Backlash - Mist Body Iron Man - Character Brass - Armored Powerhouse & Weapons Array Jubilee - Prismatic Flare Curse - Brutal Dissection Juggernaut - Battering Ram Darkness - Demigod of the Dark Rogue - Mutant Misslile Events - Witchblade on the Scene Scarlet Witch - Hex Power & Sorceress Slam (Non-Error) Grifter - Nerves of Steel Grunge - Danger Seeker IQ Killrazor - Outer Fury Any Hero - Power Leech Malebolgia - Character & Signed in Blood Apocalypse - Character Overtkill - One-Man Army Bishop - Character & Temporal Anomaly Ripclaw - Character & Native Magic Cable - Character & Askani' Son Shadowhawk - Backsnap & Brutal Revenge Carnage - Anarchy Spawn - Protector of the Innocent Deadpool - Don't Lose Your Head! Stryker - Armed and Dangerous Doctor Doom - Character & Diplomatic Immunity Tiffany - Character & Heavenly Agent Dr. Strange - Character Velocity - Internal Hardware, Quick Thinking, & Speedthrough Iron Man Character Violator - Darklands Army Ghost Rider - Character Voodoo -

Descargar Texto En

Revista Sans Soleil Estudios de la imagen Hijos del átomo: la mutación como génesis del monstruo contemporáneo. El caso de Hulk y los X-Men en Marvel Comics José Joaquín Rodríguez Moreno* University of Washington RESUMEN La Era Atómica engendró un nuevo tipo de monstruo, el mutante. Esta criatura fue explotada en las historias de ciencia ficción y consumida principalmente por una audiencia adolescente, pero fue más que un simple monstruo. A través de un análisis detenido, el mutante puede mostrarnos los miedos y las expectativas que despertaba en su público. Para lograr eso, necesitamos conocer el modo en que estas historias eran creadas, cuál fue su contexto histórico y qué temas desarrollaron los autores. Este trabajo estudia dos casos concretos producidos en Marvel Comics durante los primeros años sesenta: Hulk y los X-Men, gracias a los cuales sabremos más sobre el tiempo y la sociedad en que fueron producidos. PALABRAS CLAVE: Monstruo, Mutante, Era Atómica, Cómics, Estudios culturales. ABSTRACT: The Atomic Age spawned a new monster type – the mutant. This creature was exploited in science fiction narratives and mostly consumed by a teenage audience, but it was more than a mere monster. Through an inquisitive analysis we can learn about the nightmares and hopes that mutants represented for its audience. In order to do it, we need to learn how these narratives were created, what was its historical context and what topics were portrayed by the authors. We are studying two concrete cases from Marvel Comics in the early 60s – Hulk and the X-Men, which will show us more about their time and society. -

|||GET||| Damage Control 1St Edition

DAMAGE CONTROL 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Lisa Renee Jones | 9781250083838 | | | | | Damage Control (comics) Hoag hints at a secret past with Cage. Maybe the concept doesn't hold up to such a voluminous collection, and is better handled in smaller bites. Damage Control 1st edition and now needs the good doctor to cough up the Damage Control 1st edition. Published Jun by Marvel. Art by Ernie Colon. And a notary. Spider-Man remains trapped inside. Damage Control is a fictional construction company appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Issue ST. Sign In Don't Damage Control 1st edition an Damage Control 1st edition Would have been better if more episodic. During the reconstruction, a strange side-effect of one of the Hulk's destroyed machines causes the Chrysler Building to come to life. And even that first miniseries did have its moments, like Wolverine getting a pie in the face, and the Danger Room creating a tiny robot Groucho Marx. John Wellington. Start Your Free Trial. Published Aug by Marvel. Damage Control 1st edition his battle against Declun and Damage Control, which includes destroying many D. It's just how generic he is without any real motivation or interesting characteristics. Retrieved October 3, Read a little about our history. I picked this collection up to read more of the inanity, and was taken back briefly to the novelty of it all. Several of the employees meet and discuss the problem with other cosmic entities, such as Galactus and Lord Chaos. It's also not clear why Robin Chapel is so frequently sidelined. -

Calabozo 26.FH10

Salgo del departamento de mi hermana a las 8:00 a.m. en punto. Me lleva media hora llegar Calabozo del Androide nº 26 / Octubre a la universidad caminando. En mi ruta encontré 2005 hoy unos negativos junto a otra basura en la calle. El voyerista que hay en mí no pudo resistirse Director/Editor a recoger aquellos negativos. Aparentemente Sergio Alejandro Amira son de un viaje, aparentemente de una familia, hay una foto donde aparece un hombre, una Diagramación y Dirección de Arte mujer y dos niños. ¿Quiénes serán?, ¿en que Sergio Alejandro Amira sitio tomaron sus fotos? Se las mostré a un compañero de curso, me dijo que parecía San Portada Pedro de Atacama. La mayoría de las fotos son John Cassaday de cactus, playas, carreteras, iglesias, hay una donde se distingue un letrero que dice Chungará, Colaboradores altura 4.500 metros. El Chungará es uno de los David Mateo lagos más altos del mundo a 4.517m de altitud Daniel Vak Contreras y se encuentra a los pies de los volcanes gemelos Payachatas y las lagunas Cotacotani, en el Norte Grande chileno. Estoy seguro que nunca iré por esos lados, odio viajar. exxSupongo que podría escribir que gracias a esa familia anónima y a los negativos desechados de sus maravillosas vacaciones me vi mágicamente transportado al desierto chileno y blablablá, pero no lo haré. No quiero saber nada de desiertos ni de familias chilenas de vacaciones, sentido y en el mismo sujeto describe muy bien ¿habrá algo más detestable que una familia de el principio de incertidumbre de Heisenberg que vacaciones? Odio las vacaciones.