Chinese Antarctica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-22 Antarctic & Sub-Antarctic Sea Voyages Brochure

ANTARCTIC AND SUB-ANTARCTIC SEA VOYAGES 2021·22 SE ASO N The Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) | South Georgia | Antarctic Peninsula Exclusive Partner's Edition ANTARCTIC PENINSULA AND SOUTH SHETLAND ISLANDS SOUTH AMERICA Falkland Islands (Malvinas) CHILE Punta Arenas Port Stanley Atacama Desert (Chile) PACIFIC OCEAN Ushuaia ATLANTIC (Argentina) OCEAN Santiago Puerto Williams (Chile) South Georgia and the Cape Horn South Sandwich Islands (Chile) Puerto Montt Drake Passage SOUTH SHETLAND South Orkney Islands ISLANDS Elephant Island Torres del Paine King George Island Frei Station (Chile) Punta Arenas Fildes Bay Livingston Island Half Moon Island Hannah Point Deception Bransfield Strait Island Joinville Island O'Higgins Trinity Island Station Esperanza Brabant Island Gerlache (Chile) Strait Station Anvers Island (Argentina) ANTARCTICA Port Lockroy (UK) Paradise Bay Petermann Island Almirante Vernadsky Station Brown Station (Ukraine) (Argentina) Biscoe Island WEDDELL SEA Antarctic Polar Circle ANTARCTIC PENINSULA SUMMARY 5 Discover Antarctica and the 19 DATES & PRICES 28 PLANNING YOUR TRIP Southern Ocean 20 Dates & Prices 29 Arrival and Departure Details 6 Traveling on our Small Expedition Ships 21 Inclusions & Exclusions 30 Flight and Hotel Package 8 Our Company 31 Packing for Your Trip 22 EXPERIENCES & ADVENTURES 32 Useful Tips 9 ITINERARIES 23 The Antarctica21 Expedition 33 Important Trip Details 11 Falklands (Malvinas) & South Georgia Experience 12 Antarctica, South Georgia & 24 Sea Kayaking in Antarctica 35 TERMS & CONDITIONS The Falkland Islands 25 Hiking and Snowshoeing in Antarctica 14 Antarctic Small Ship Expedition 26 Life on Board 27 Education Program 15 VESSELS 16 Magellan Explorer 18 Ocean Nova Travel with Antarctica21 for a transformative, once-in-a-lifetime experience Hiking in Antarctica © K. -

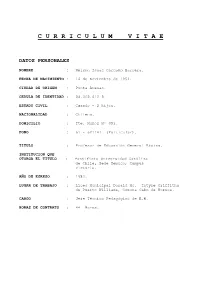

C U R R I C U L U M V I T

C U R R I C U L U M V I T A E DATOS PERSONALES NOMBRE : Nelson Isaac Cárcamo Barrera. FECHA DE NACIMIENTO : 16 de Noviembre de 1951. CIUDAD DE ORIGEN : Punta Arenas. CEDULA DE IDENTIDAD : 06.305.413-5 ESTADO CIVIL : Casado – 2 hijos. NACIONALIDAD : Chilena. DOMICILIO : Tte. Muñoz Nº 093. FONO : 61 – 621147 (Particular). TITULO : Profesor de Educación General Básica. INSTITUCION QUE OTORGA EL TITULO : Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Sede Temuco, Campus Victoria. AÑO DE EGRESO : 1983. LUGAR DE TRABAJO : Liceo Municipal Donald Mc. Intyre Griffiths de Puerto Williams, Comuna Cabo de Hornos. CARGO : Jefe Técnico Pedagógico de E.M. HORAS DE CONTRATO : 44 Horas. ANTECEDENTES PROFESIONALES : Agosto - 1983. Certificado de Practica Profesional en Escuela G-217 California,de la I. Municipalidad de Victoria , IX Región de la Araucanía. Agosto-Diciembre 1984. Decreto Exento Nº 333 del 17 de Octubre de 1984, suplencia en Escuela F-98 Michigan , dependiente de la I. Municipalidad de Collipulli, IX Región de la Araucanía. Años 1985 -1987 : Decreto Nº 008 del 29 de Marzo de 1985, asume de Titular como Docente en la Escuela G – 214 de Trangol, dependiente de la I.Municipalidad Victoria. IX Región. Años 1987 -1991 : Decreto Exto. Nº 014 del 26 de Febrero de 1987, designa Director de la Escuela F -226 Quino, dependiente de la I. Municipalidad de Victoria, IX Región. Noviembre.1991 – Marzo 1992 : Oficio Nº 638 del 7 de Octubre de 1991, obtiene por Concurso Público la Dirección de la Escuela G – 43 de la Comuna de Timaukel, XII Reg. de Magallanes Antártica Chilena. -

Dientes De Navarino Circuit TREK 7 Days Wilderness Trekking on the Isla Navarino - Tierra Del Fuego

Dientes de Navarino Circuit TREK 7 days Wilderness Trekking on the Isla Navarino - Tierra del Fuego The “Dientes de Navarino Circuit” is a trekking experience at the edge of the world! This southernmost trekking route is a once-in-a-lifetime experience that will fascinate curious and experienced hikers. On this pioneer-adventure in the mountains of Dientes de Navarino, you will land right in the middle of Tierra del Fuego’s mystic beauty. Hike through wet swampland and quaint forests of beech trees before you finally reach the sharp teeth, Los Dientes, of Navarino Island. These natural jewels are embedded in small blue-lustrous lagoons. Also hike through the southern end of the world to watch beavers building their dams, while resisting the extremely strong gusts of wind that indicate the closeness of Cape Horn. Trip Highlights: • Hike the southernmost trek at the edge of the world, the Dientes de Navarino Circuit on Isla Navarino • Set up camp between rock pinnacles, alpine lakes & beaver dams • Visit the charming fishing village Puerto Williams, the most southerly village in the world • Fly over the legendary Strait of Magellan, Darwin mountain range and Beagle-Channel • Enjoy a freshly caught king crab prepared by a local family Insider Tip: • Take a trip from Ushuaia to Martillo Island and learn more about see lions, dolphins and Magellan penguins Trip Info: Trip length: 7 days Start/End of the trip: from / to Punta Arenas or Ushuaia Group Size: min. 3 / max. 12 people Departures: see set departures on our website or individual on -

Magallanes and Antártica Chilena Region ROAD MAP REGION Climate Activities During the in Nature Tips Magallanes Summer, There Are Approximately 18 TREKKING

MAGALLANES AND ANTÁRTICA CHILENA REGION ROAD MAP REGION Climate Activities During the in Nature Tips MAGALLANES summer, there are approximately 18 TREKKING. Due to its geographical - Shops are open from 10:00 a.m. - Torres del Paine National Park is AND ANTÁRTICA diversity and spectacular natural to 1:00 p.m. and from 3:00 p.m. to managed by the CONAF (National hours of daylight. scenery, this region is possibly one 8:00 p.m. Forestry Corporation). You must CHILENA of the best trekking destinations - Both hotels and shops take credit carry identification and register Due to its vastness, the Magallanes in Chile. It is essential to protect cards. However, it is essential before entering the park. and Antártica Chilena Region wildlife on all trails and not leave to have Chilean pesos to pay - Camping is only allowed in Stunning Patagonia. presents important climate any garbage behind. for everyday expenses such as places authorized by the park VALLE del FrancÉS, torres del paine national park variations that are mainly Noteworthy places. The W and transportation and tickets, or shop administration. Trips should be influenced by the region’s Macizo Paine circuits at the Torres WHALE WATCHING. One of the gauchos (cowboys) that herd their in grocery stores. planned in advance, because topography, the sea, and strong del Paine National Park. The Dientes most important cetaceans is the sheep from one ranch to another. - Banks and ATMs can be found all campsites require prior winds that increase during de Navarino circuit at Isla Navarino. humpback whale, which roams the They are also part of the Magellanic in all the provincial capitals of reservation. -

Antarctica & South Georgia

BirdLife Australia & Aurora Expeditions present Antarctica & South Georgia NOVEMBER 2016 LIMITED TIME OFFER PARTNERS FLY FREE* See inside for details JOIN US IN ANTARCTICA We invite you to join us aboard our small expedition ship, Polar Pioneer, for an exclusive BirdLife Australia voyage to Antarctica & South Georgia. Enjoy magnificent birdwatching from the ship’s observation decks and as we land ashore, where our expert guides, including a BirdLife Australia specialist, identify and explain each species. From gentoo and king penguins to wandering albatrosses and Antarctic skuas, this is your chance to experience some of the most unique and mesmerising birdlife on our planet. Be mesmerised by albatrosses as they wheel in our wake. 24 DAYS BIRDLIFE AUSTRALIA PACKAGE FEATURING ANTARCTICA & SOUTH GEORGIA EXPEDITION AND BONUS SANTIAGO BIRD TOUR. This exclusive BirdLife Australia package also features international flights, accommodation, city tour and more! ITINERARY 16 November 2016 | Australia > Santiago, Chile Yellow-finch, Magellanic Tapaculo, Scale-throated Earthcreeper, Andean Depart Australia on your LAN Airlines flight to Santiago. On arrival you’ll Condor, Mountain Caracara, may be spotted during the day. (B) be transferred to your hotel. 19 November 2016 | Santiago > Falkland Islands/Malvinas Overnight: Atton El Bosque Santiago After breakfast proceed to the airport to check-in for your LAN flight to 17 November 2016 | Santiago City Tour the Falkland Islands. The flight will arrive in the Falklands early afternoon Enjoy a half-day panoramic sightseeing tour of Santiago, visiting some of where, after a short tour of the town, you’ll be transferred to Polar the city’s most important landmarks. -

Across the Antarctic Circle

Across the Antarctic Circle 02 – 11 March 2019 | Polar Pioneer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians and remote places on our planet. With over 27 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow for destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a fulfilling a truly intimate experience with nature. and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every opportunity for lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Saturday 2 March 2019 Puerto Williams Position: 21:30 hours Course: 139° Wind Speed: 18 knots Barometer: 997.3 hPa Latitude: 55°05’ S Speed: 111.8 knots Wind Direction: NNW Air Temp: 8°C Longitude: 66°59’ W Sea Temp: 8°C After months of planning, weeks of anticipation and long-haul flights from around the globe, The sound of seven-short-one-long rings from the ship’s signal system was our cue to don we took a final flight from Punta Arenas to arrive at Puerto Williams, Chile, raring to begin our warm clothes, bulky orange lifejackets and gather at the muster stations to sample the ambi- Antarctic adventure. -

Preliminary Key to Tlie Mosses of Isia Navarino, Chile (Prov

Nova Hedwigia, Beiheft 138,215-229 Article Stuttgart, November 2010 Preliminary key to tlie mosses of Isia Navarino, Chile (Prov. Antartica Chilena) William R. Buck^ and Bernard Goffinet^ ' Institute ofSystematic Botany, The New Yorl< Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY10458-5126, U.S.A. ^ Department ofEcology and Evolutionary Biology, 75North Eagleville Road, Universityof Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269-3043, U.S.A. With 6 figures Abstract: Isla Navarino is the southernmost permanently inhabited island in the world. The forests are dominated by Nothofagus spp. and the bedrock isacidic. To date 157 taxa of mosses have been collected from the island. The taxa are keyed and achecklist provides the voucher specimen information upon which the key was based. Key words:Chile, IslaNavarino, Provincia Antartica Chilena, subantarctic bryoflora. Introduction Isla Navarino is the largest of the Chilean Antarctic Islands, lying directly south of the Beagle Channel, opposite Argentinean Tierra del Fuego (Fig. 1). It is ca. 4000 km^ The island is the southernmost permanently inhabited island inthe world, but it is not heavily populated. The pro vincial capital, Puerto Williams, hosts most ofthe population and has only about 1100 people, mostly connected with the military base there. The entire Cape Horn Archipelago (including I. Navarino) has been declared a Biosphere and World Heritage Site by UNESCO (Rozzi et al. 2004). Although lying between 54°52'S and55°18'S latitude (and between 67° 03' W and 68° 22' W longitude), the temperature is reasonably mild because of the oceanic conditions. At lower el evations, the forests are dominated by three species of Nothofagus. Many of the forests are es sentially undisturbed. -

Yaghan's, Explorers and Settlers

YAGHAN’S, EXPLORERS AND SETTLERS: 10,000 years of Southern Tierra del Fuego Archipelago History The Museum Permanent Exhibit Script Martin Gusinde Anthropological Museum · Puerto Williams - Chile Participants in Initiation Rite in the year 1922. (Martin Gusinde, last row, fourth position from left to right). Anthropos Institut. Sankt Augustin, Germany - Authorized Digital Copying Martin Gusinde Anthropological Museum Introduction INTROUDUCTION The creation of a museum on Navarino Island was an ambitious project that grew out of a deep interest in and concern for the island’s natural and cultural heritage. The initiative was originally proposed by the Chilean Navy, the same institution that built the Martín Gusinde Anthropological Museum (MAMG), which opened its doors in Puerto Williams in 1975. In the 1960s, before the museum was founded, a collection was begun of archeological material from the island’s coastal areas, along with some objects of historical interest from the first occupation by pioneers. This collection was exhibited in the now defunct Mixed School Nº in Puerto Williams. The collection was moved when the Martin Gusinde Museum was established, becoming part of that institution permanent collection. The Museum was named after the Austrian anthropologist and priest Martin Gusinde S.V.D. (1886-1969), who worked among the Yaghan and Selk’nam people from 1918 to 1924. His body of work offers the greatest collection of ethnographic studies about a world that was already on the verge of disappearing. His seminal work “The Indians of Tierra del Fuego” was published between 190 and 1974, and will forever remain the principal source of information we possess about the native people of Tierra del Fuego. -

Redalyc.Descubrimiento E Implementación Del Pájaro Carpintero Gigante (Campephilus Magellamcus) Como Especie Carismática

Magallania ISSN: 0718-0209 [email protected] Universidad de Magallanes Chile ARANGO, XIMENA; ROZZI, RICARDO; MASSARDO, FRANCISCA; ANDERSON, CHRISTOPHER B.; IBARRA, TOMÁS Descubrimiento e implementación del pájaro carpintero gigante (Campephilus Magellamcus) como especie carismática: una aproximación biocultural para la conservación en la reserva de biósfera Cabo de Hornos Magallania, vol. 35, núm. 2, 2007, pp. 71-88 Universidad de Magallanes Punta Arenas, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=50635206 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MAGALLANIA, (Chile), 2007. Vol. 35(2):71-88 71 DESCUBRIMIENTO E IMPLEMENTACIÓN DEL PÁJARO CARPINTERO GIGANTE (CAMPEPHILUS MAGELLANICUS) COMO ESPECIE CARISMÁTICA: UNA APROXIMACIÓN BIOCULTURAL PARA LA CONSERVACIÓN EN LA RESERVA DE BIOSFERA CABO DE HORNOS XIMENA ARANGO*, RICARDO ROZZI*/**, FRANCISCA MASSARDO*, CHRISTOPHER B. ANDERSON* Y TOMÁS IBARRA*/*** RESUMEN Al sur de Sudamérica se encuentra la Reserva de Biosfera Cabo de Hornos donde persisten los bosques siempreverdes subantárticos. Esta zona, considerada una de las más prístinas del mundo, está sometida a presiones crecientes de conectividad, crecimiento urbano y desarrollo turístico, sin embargo, todavía alberga bosques no frag- mentados de Nothofagus. Con una aproximación biocultural a la conservación determinamos que el pájaro carpintero gigante (Campephilus magellanicus) es la especie de ave preferida por la comunidad de Puerto Williams, capital de la Provincia Antártica Chilena, ciudad más austral del mundo y mayor asentamiento humano de la reserva. -

Folleto17 Final

Welcome to Patagonia & Cape Horn The World's Southernmost HeliFishing Experience Cape Horn EXPLORING THE CAPE HORN WATERSHED Torres del Paine Río Grande Punta PATAGONIA Arenas Tierra del Fuego AT THE SOUTHERNMOST TIP OF THE Ushuaia AMERICAS LAKUTAIA Puerto Williams Isla Navarino Within the UNESCO Cape Horn Biosphere, recognized as Cape Horn one of the 24 most pristine areas on the planet, is Isla Navarrino and Puerto Williams, the southernmost city in the world. LAKUTAIA LODGE is located on Navarino Island in a wild and remote area. The name “Lakutaia” means “Bay of the Royal Cormorant “in the language of the Yamana, one of the original indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego. Puerto Williams For those that love fly fishing, having the chance to fish in such a remote and rarely visited area containing many lakes and rivers teeming with large wild trout is a very exciting opportunity and only a dream for most fly fishermen. We invite you to make this dream a reality and join us at the southernmost area of the planet to challenge your skills fly fishing for large Brown Trout, Brook Trout, Rainbow Trout, and Sea Run Trout. The heart of the last frontier is only a short helicopter flight from the lodge. You will fly to some of the most remote rivers, lakes and lagoons in the world. The varying types of water available present the fisherman with an interesting array of fishing options. FISHING INFORMATION - Access to all Lodge activities ( kayaking, and mountain bikes). - Navarino Island offers fishing in the southernmost river of Chilean - Free drinks (Premium liquors excluded). -

The Effects of Globalization on Artisanal Fisheries in the Magellan and Chilean Antarctic Region

The Effects of Globalization on Artisanal Fisheries in the Magellan and Chilean Antarctic Region María Fernanda Morales Camacho University of Amsterdam MSc International Development Studies (Research) The Netherlands, 2018 Images: Personal archive. University of Amsterdam Graduate School of Social Sciences MSc International Development Studies (Research) Title: The Effects of Globalization on Artisanal Fisheries in the Magellan and Chilean Antarctic Region Student: María Fernanda Morales Camacho Email: [email protected] Date: June 23rd, 2018 UvA ID: 11254750 Word Count: 31 385 words Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Maarten Bavinck Department of Geography, Planning International Development Studies, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Second reader: Prof. Dr. Jahn Petter Johnsen The Norwegian College of Fishery Science, University of Tromsø, Norway 2 Abstract Globalization and changes in international markets have effected the local level by defining and redefining the local production schemes, excluding or including actors, transforming local cultures, and influencing the ecosystems’ sustainability. While there is vast literature about local and global economic interactions and value chains of various fisheries, there are no studies on the value chain and socioeconomic issues of the southern king crab. Therefore, this research aims to understand the consequences of global fishing markets on the Magellan and Chilean Antarctic regions by studying the history and value chain of this fishery and the effects of global value chains (GVC) on the social well-being of those artisanal fishers involved in this activity. A mixed-methods approach was applied, employing observations, semi-structured and unstructured in-depth interviews, and a survey with the fishers and key informants. This study finds a simplification in the production requirements due to the new markets’ preferences oriented in less processed seafood. -

Antarctica Program 2020 Copia

ANTARCTICA, THE UTTERMOST LAND IN EARTH LAKUTAIA LODGE INVITES YOU TO BE PART OF THIS ONCE IN A LIFE-TIME ADVENTURE Visiting the White Continent has been the dream of many adventurers along the history. Today, LAKUTAIA LODGE invites you to be part of this unique • 05 DAYS/ 04 NIGHTS adventure. In this amazing land, it is found the biggest sweet water reserve in the world, home of an innumerable land and sea fauna. Its unique beauty contrasts with the extreme weather giving as a result Antarctic to be an exotic and hypnotizer destination for those who have the fortune to reach this remote territory. www.lakutaia.com ITINERARY: DAY 01 PUNTA ARENAS - PUERTO WILLIAMS O USHUAIA / PUERTO WILLIAMS FROM UNTA ARENAS: Fly on Aerovias DAP to Puerto Williams. During the flight enjoy the overwhelming views of amazing landscapes, the Strait of Magellan, the beautiful glaciers of Darwin Mountain Range, and the Beagle Channel. (Flight time will vary from 50 minutes to 1h20, according to the aircraft available on the day). Reception and short transfer to LAKUTAIA LODGE. FROM USHUAIA: After immigration process and port-tax payment at Ushuaia’s port in Argentina, sail across the Beagle Channel to reach, after approximately 30 minutes, Puerto Navarino in the Chilean side. The navigation is performed on board a small-size-semi-rigid motor-boat. Upon arrival at Puerto Navarino, you will be transferred on a 54-km/34 mile ride to Puerto Williams (1h40 approx.) to do the immigration process in Chile. Once this process is completed, you will be transferred to LAKUTAIA LODGE to enjoy a welcome aperitif and lunch.