The Educational Television Station in Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VAB Member Stations

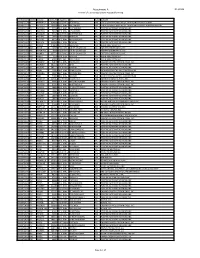

2018 VAB Member Stations Call Letters Company City WABN-AM Appalachian Radio Group Bristol WACL-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WAEZ-FM Bristol Broadcasting Company Inc. Bristol WAFX-FM Saga Communications Chesapeake WAHU-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WAKG-FM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WAVA-FM Salem Communications Arlington WAVY-TV LIN Television Portsmouth WAXM-FM Valley Broadcasting & Communications Inc. Norton WAZR-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WBBC-FM Denbar Communications Inc. Blackstone WBNN-FM WKGM, Inc. Dillwyn WBOP-FM VOX Communications Group LLC Harrisonburg WBRA-TV Blue Ridge PBS Roanoke WBRG-AM/FM Tri-County Broadcasting Inc. Lynchburg WBRW-FM Cumulus Media Inc. Radford WBTJ-FM iHeart Media Richmond WBTK-AM Mount Rich Media, LLC Henrico WBTM-AM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WCAV-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WCDX-FM Urban 1 Inc. Richmond WCHV-AM Monticello Media Charlottesville WCNR-FM Charlottesville Radio Group (Saga Comm.) Charlottesville WCVA-AM Piedmont Communications Orange WCVE-FM Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVE-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVW-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCYB-TV / CW4 Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WCYK-FM Monticello Media Charlottesville WDBJ-TV WDBJ Television Inc. Roanoke WDIC-AM/FM Dickenson Country Broadcasting Corp. Clintwood WEHC-FM Emory & Henry College Emory WEMC-FM WMRA-FM Harrisonburg WEMT-TV Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WEQP-FM Equip FM Lynchburg WESR-AM/FM Eastern Shore Radio Inc. Onley 1 WFAX-AM Newcomb Broadcasting Corporation Falls Church WFIR-AM Wheeler Broadcasting Roanoke WFLO-AM/FM Colonial Broadcasting Company Inc. Farmville WFLS-FM Alpha Media Fredericksburg WFNR-AM/FM Cumulus Media Inc. -

Hampton Harrisonburg Haymarket Herndon Highland Springs Hillsville

Virginia Radio Highland Springs Lexington 'WLUR(FM )-Feb 27, 1967: 91.5 mhz; 225 w. Ant WCLM(AM) -May 18, 1959: 1450 khz; 1 kw -D, 250 w -N, DA-1. 4719 Nine Mile Rd., Richmond (23223). minus 75 ft. Stereo. Washington and Lee U. (24450). (804) 222 -7000. Momentum Broadcasting Inc. Net: (703) 463-8443, 8444, 8445. Washington & Lee U. Robert J. Hampton Sheridan, CNN. Format: All news. Tyrone Dickerson, Format: Div. John D. Wilson, pres; de pres & gen mgr; Jackie Williams, bus mgr; Ed Maria, gen mgr; Thomas Tinsley, chief engr. WHOV(FM) -March 5, 1964: 88.3 mhz; 1.25 kw. Ant 25; Burkhardt, chief engr. Rates: $27; 25; 23. WREL(AM) -Nov 14, 1948: 1450 khz; 1 kw -U. Drawer 200 ft. Stereo. Hampton Institute (23668). (804) 902 (24450). (703) 463 -2161. Equus Communications Institute. Format: Black, jazz. *WHCE(FM) -Sep 29, 1980: 91.1 mhz; 3 kw. Ant 103 727 -5407. Hampton Inc. (acq 11.85). Net: MBS, AP, Agrinet Farm. Rep: Henrico County Spec prog: Class 4 hrs, Sp 4 hrs wkly. Lucious ft. Box 99 (23075). (804) 737-3691. Keystone. Format: Modern country. Spec prog: Farm Format: Div. Adam gen mgr; Ed Wyatt, pres; Frank Sheffield, gen mgr; Audrey Jordan, Schools. Stubbs, 3 hrs wkly. Jim Putbrese, pres; Jim Pounds, gen Matthews, chief engr. prog dir; Robert Graul, chief engr. mgr; Jim Bresnahan, news dir; Earl Ray, chief engr. Rates: $15; 13; 15; 12. WPEX(AM) -July 1, 1948: 1490 khz; 1 kw -U, DA-1. 32 E. Mellen St. (23663). (804) 728 -1490. -

Bangor, ME Area Radio Stations in Market: 2

Bangor, ME Area Radio stations in market: 2 Count Call Sign Facility_id Licensee I WHCF 3665 BANGOR BAPTIST CHURCH 2 WJCX 421 CSN INTERNATIONAL 3 WDEA 17671 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC 4 WWMJ 17670 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC 5 WEZQ 17673 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC 6 WBZN 18535 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC 7 WHSN 28151 HUSSON COLLEGE 8 WMEH 39650 MAINE PUBLIC BROADCASTING CORPORATION 9 WMEP 92566 MAINE PUBLIC BROADCASTING CORPORATION 10 WBQI 40925 NASSAU BROADCASTING III, LLC II WBYA 41105 NASSAU BROADCASTING III, LLC 12 WBQX 49564 NASSAU BROADCASTING III, LLC 13 WERU-FM 58726 SALT POND COMMUNITY BROADCASTING COMPANY 14 WRMO 84096 STEVEN A. ROY, PERSONAL REP, ESTATE OF LYLE EVANS IS WNSX 66712 STONY CREEK BROADCASTING, LLC 16 WKIT-FM 25747 THE ZONE CORPORATION 17 WZON 66674 THE ZONE CORPORATION IH WMEB-FM 69267 UNIVERSITY OF MAINE SYSTEM 19 WWNZ 128805 WATERFRONT COMMUNICATIONS INC. 20 WNZS 128808 WATERFRONT COMMUNICATIONS INC. B-26 Bangor~ .ME Area Battle Creek, MI Area Radio stations in market I. Count Call Sign Facility_id Licensee I WBCH-FM 3989 BARRY BROADCASTING CO. 2 WBLU-FM 5903 BLUE LAKE FINE ARTS CAMP 3 WOCR 6114 BOARD OF TRUSTEES/OLIVET COLLEGE 4 WJIM-FM 17386 CITADEL BROADCASTING COMPANY 5 WTNR 41678 CITADEL BROADCASTING COMPANY 6 WMMQ 24641 CITADEL BROADCASTING COMPANY 7 WFMK 37460 CITADEL BROADCASTING COMPANY 8 WKLQ 24639 CITADEL BROADCASTING COMPANY 9 WLAV-FM 41680 CITADEL BROADCASTING COMPANY 10 WAYK 24786 CORNERSTONE UNIVERSITY 11 WAYG 24772 CORNERSTONE UNIVERSITY 12 WCSG 13935 CORNERSTONE UNIVERSITY 13 WKFR-FM 14658 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC 14 WRKR 14657 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC 15 WUFN 20630 FAMILY LIFE BROADCASTING SYSTEM 16 WOFR 91642 FAMILY STATIONS, INC. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-1-200204-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/04/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000104614 Renewal of FM WZYQ 191535 Main 101.7 MOUND BAYOU, FENTY FUSS 02/03/2020 Accepted License MS For Filing 0000104644 Renewal of FM WLAU 52618 Main 99.3 HEIDELBERG, MS TELESOUTH 02/03/2020 Accepted License COMMUNICATIONS, For Filing INC. 0000104223 Renewal of FM WKIS 64001 Main 99.9 BOCA RATON, FL ENTERCOM 01/31/2020 Received License LICENSE, LLC Amendment 0000104700 Renewal of FM KQKI-FM 64675 Main 95.3 BAYOU VISTA, LA Teche Broadcasting 02/03/2020 Accepted License Corporation For Filing 0000104619 Renewal of AM KAAY 33253 Main 1090.0 LITTLE ROCK, AR RADIO LICENSE 02/03/2020 Accepted License HOLDING CBC, LLC For Filing 0000103459 Renewal of FX K237GR 154564 95.3 JOHNSON, AR HOG RADIO, INC. 01/31/2020 Accepted License For Filing 0000103767 Renewal of AM WGSV 25675 Main 1270.0 GUNTERSVILLE, GUNTERSVILLE 01/31/2020 Received License AL BROADCASTING Amendment COMPANY, INC. 0000104204 Renewal of FM WQMP 73137 Main 101.9 DAYTONA BEACH ENTERCOM 01/31/2020 Received License , FL LICENSE, LLC Amendment Page 1 of 33 REPORT NO. PN-1-200204-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/04/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

Harrisonburg, VA (United States) FM Radio Travel DX

Harrisonburg, VA (United States) FM Radio Travel DX Log Updated 4/27/2018 Click here to view corresponding RDS/HD Radio screenshots from this log http://fmradiodx.wordpress.com/ Freq Calls City of License State Country Date Time Prop Miles ERP HD RDS Audio Information 88.7 WXJM Harrisonburg VA USA 4/18/2018 1:48 PM Tr 2 390 RDS RDS hit 89.3 WVTU Charlottesville VA USA 4/18/2018 1:48 PM Tr 26 195 RDS "WVTF" - public radio 90.1 WPVA Waynesboro VA USA 4/18/2018 1:48 PM Tr 29 2,500 RDS "Spirit FM" - ccm 90.7 WMRA Harrisonburg VA USA 4/18/2018 1:50 AM Tr 10 21,500 RDS public radio 91.1 WTJU Charlottesville VA USA 4/18/2018 2:46 PM Tr 37 1,500 RDS RDS hit 91.7 WEMC Harrisonburg VA USA 4/18/2018 1:48 PM Tr 3 1,850 RDS RDS hit 92.5 WINC-FM Winchester VA USA 4/18/2018 1:51 PM Tr 57 22,000 "92.5 Wink FM" - hot AC 92.7 WCVL-FM Charlottesville VA USA 4/18/2018 2:46 PM Tr 37 750 RDS RDS hit 93.3 WFLS-FM Fredericksburg VA USA 4/18/2018 1:51 PM Tr 77 50,000 "93.3 WFLS" - country 93.7 WAZR Woodstock VA USA 4/18/2018 1:51 PM Tr 18 8,500 RDS "93-7 Now" - CHR 94.1 WQZK-FM Keyser WV USA 4/18/2018 1:55 PM Tr 68 1,300 "94-1 QZK" - CHR 94.3 WTON-FM Staunton VA USA 4/18/2018 1:55 PM Tr 32 340 94.7 W234AH Harrisonburg VA USA 4/18/2018 1:55 PM Tr 6 10 religious 95.1 W236BG Harrisonburg VA USA 4/18/2018 1:55 PM Tr 3 25 "WNRN" - variety 95.3 WZRV Front Royal VA USA 4/18/2018 1:57 PM Tr 51 6,000 "The River 95-3" - classic hits 95.5 WBOP Buffalo Gap VA USA 4/18/2018 1:57 PM Tr 27 6,000 RDS 96.1 WMQR Broadway VA USA 4/18/2018 1:57 PM Tr 11 2,600 HD RDS "More 96-1" - -

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

2011-12 University of Arkansas Razorback Women's

UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS RAZORBACK WOMEN’SWOMEN’S BASKETBALLBASKETBALL GAMEGAME NOTESNOTES 11 GAME 24 // Feb.FEB. 12,12, 20122012 12 2011-12 UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS RAZORBACK WOMEN’S HOOPS GAME 24 // AUBURN // FEB. 12, 2012// 1:45 p.m. ASSOCIATE MEDIA RELATIONS DIRECTOR JERI THORPE || 131 BARNHILL ARENA || FAYETTEVILLE, AR 72701 || W: 479-575-5037 || C: 479-283-3344 || E: [email protected] 2011-12 SCHEDULE Arkansas (18-5, 7-4) at Auburn (11-14, 3-9 SEC) Sunday, Feb. 12, 2012 // Auburn Arena (19,200) // Auburn, Ala. & RESULTS Radio: Little Rock - KABZ-FM - 103.7; Fayetteville - KAKS-FM - 99.5; Fayetteville - KUOA-AM 18-5 (7-4 SEC) -1290 (FM translators 105.3 and 97.9); Berryville - KTHS-AM - 1480; Fort Smith - KFPW-AM - 1230; Barling - KFPW-FM - 94.5; Rogers - KURM-AM - 790 TV: ESPN2 // Video: ESPN2 // Live Stats: ArkansasRazorbacks.com -For FTP Video services please contact Blair Cartwright in New Media at 479-575- NOVEMBER (5-1) 6421 or [email protected]. Exhibition Game 2 Newman University FAYETTEVILLE W, 63-35 ARKANSAS CONTINUES SEC Play MEDIA INFORMATION WBI Tip-Off Classic -Arkansas has won a program-best Media Relations 11 vs. Minnesota! Daytona, Fla. L, 60-68 Arkansas ................................. Jeri Thorpe seven SEC games in a row. Office ................................ 479-575-5037 12 vs. South Florida! Daytona, Fla. W, 65-61 (ot) Cell ................................... 479-283-3344 13 vs. #13 Fla State! Daytona, Fla. W, 55-52 -Senior Ashley Daniels has had seven Email ............................. [email protected] 16 Texas-Arlington [rv] FAYETTEVILLE W, 57-34 Website .............. ArkansasRazorbacks.com 20 Utah [rv] FAYETTEVILLE W, 57-56 consecutive games scoring in double Opponent ...............................Matt Crouch 25 Grambling State [rv] FAYETTEVILLE W, 69-49 figures. -

Networking and 67 Expressed Degrees of Interest in Participation. a Sample

DOCUMENT RF:sumn ED 025 147 EM 000 326 By- McKenzie. Betty. Ed; And Others 17-21. 1960). Live Radio Networking for EducationalStations. NAEB Seminar (University of Wisconsin. July National Association of Educational Broadcasters,Washington, D.C. Pub Date [601 Note- 114p. Available from- The National Association of EducationalBroadcasters. Urbana. Ill. ($2.00). EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$5.80 Descriptors-Broadcast Industry. Conference Reports.*Educational Radio.*Feasibility Studies. Financial Needs, Intercommunication, National Organizations.*Networks, News Media Programing,*Radio. Radio Technology, Regional Planning Identifiers- NAEB, *National Association Of EducationalBroadcasters A National Association of EducationalBroadcasters (NAEB) seminarreviewed the development of regional live educationalnetworking and the prospectof a national network to broadcast programs of educational,cultural, and informationalinterest. Of the 137 operating NAEB radio stations,contributing to the insufficient news communication resources of the nation,73 responded to a questionnaire onlive networking and 67 expressed degreesof interestinparticipation. A sample broadcasting schedule was based on the assumptionsof an eight hour broadcast day, a general listening audience, andlive transmission. Some ofthe advantages of such a network, programed on a mutualbasis with plans for a modifiedround-robin service, would be improvededucational programing, widespreadavailability, and reduction of station operating costs. Using13 NAEB stations as a round-robinbasic network, the remaining 39 could be fed on a one-wayline at a minimum wireline cost of $8569 per month; the equivalent costfor the complete network wouldbe $17,585. As the national network develops throughinterconnection of regionalnetworks and additionof long-haultelephonecircuits,anationalheadquartersshould be established. The report covers discussiongenerated by each planningdivision in addition to regional group reports fromeducational radio stations. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

PRI 2012 Annual Report Mechanical.Ai

PRI 2012 Annual Report Mechanical 11” x 8.375” folded to 5.5” x 8.375” Prepared by See Design, Inc. Christopher Everett 612.508.3191 [email protected] Annual Report 2012 The year of the future. BACK OUTSIDE COVER FRONT OUTSIDE COVER PRI 2012 Annual Report Mechanical 11” x 8.375” folded to 5.5” x 8.375” Dear Friends of PRI, Throughout our history, PRI has distinguished itself as a nimble Prepared by See Design, Inc. organization, able to anticipate and respond to the needs of stations Christopher Everett and audiences as we fulfill our mission: to serve as a distinct content 612.508.3191 source of information, insights and cultural experiences essential to [email protected] living in an interconnected world. This experience served us well in the year just closed, as we saw the pace of change in media accelerate, and faced new challenges as a result. More and more, people are turning to mobile devices to consume news, using them to share, to interact, and to learn even more. These new consumer expectations require that we respond, inspiring us to continue to deliver our unique stories in ways that touch the heart and mind. And to deliver them not only through radio, but also on new platforms. Technology also creates a more competitive environment, enabling access to global news and cultural content that did not exist before. In this environment, PRI worked to provide value to people curious about our world and their place in it. With a robust portfolio of content as a strong foundation for growth, PRI worked to enhance our role as a source of diverse perspectives. -

Sports Talk with Bo Mattingly Is Heard

Sports Personality, LLC ⚫ 1753 N. College Ave, Fayetteville, AR 72703 ⚫ www.sportstalkwithbo.com There is power in SPORTS MARKETING and no company in Arkansas does it better. As a dedicated sports content company we work for you whether you want National, State or Local marketing. National: Being Bret Bielema launched on the national stage after being picked up by ESPNU to air as a four part series in August 2016. Our first venture into TV netted the highest watched program for ESPNU for the entire month. More exciting announcements on the “Being” series coming soon. Altogether on social media Sports Personalities reaches over 100,000 people! State: When you think sports talk in Arkansas you think Bo Mattingly. From the top of the state to the bottom and from border to border Sports Talk with Bo Mattingly is heard. 11 affiliates strong and numerous streaming options available, we’ll deliver your message to rabid sports fans on the most listened to show in Arkansas. Local: Just looking to market in NWA, we have you covered on ESPN 99.5. We’ll customize a unique marketing plan for you in the backyard of the Razorbacks on our local affiliate! Sports Talk offers a game changer when it comes to marketing your brand and getting a return on your investment. Sports Talk with Bo Mattingly message inside the content of is generally regarded as the the show in a personable, best sports talk show in authentic way. Our Arkansas because of its conversational style gives a compelling topics, “recommendation” feel that professional sound, ensures our loyal tribe of entertainment and well followers hears and known guests. -

0915 2015 VA Radio Stations.Xlsx

Radio Stations in the Commonwealth of Virginia (sorted by District) District Outlet Email Outlet Topic Media Type Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City State Postal Code 1 WESR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Oldies Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WESR-AM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Rock Music Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WESR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Oldies Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WESR-AM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Rock Music Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WCTG-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 6455 Maddox Blvd Ste 3 Chincoteague Virginia 23336-2272 1 WCTG-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 6455 Maddox Blvd Ste 3 Chincoteague Virginia 23336-2272 1 WCTG-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 6455 Maddox Blvd Ste 3 Chincoteague Virginia 23336-2272 1 WVES-FM [email protected] Country, Folk, Bluegrass; Music; News Radio Station 27214 Mutton Hunk Rd Parksley Virginia 23421-3238 2 WFOS-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 1617 Cedar Rd Chesapeake Virginia 23322 2 WNOR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Rock Music Radio Station 870 Greenbrier Cir Ste 399 Chesapeake Virginia 23320-2671 2 WNOR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Rock Music Radio Station 870 Greenbrier Cir Ste 399 Chesapeake Virginia 23320-2671 2 WJOI-AM [email protected] Music; News; Oldies Radio Station 870 Greenbrier Cir Ste 399 Chesapeake Virginia 23320-2671