Amrita Shergil and Her Contemporaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zvara 1 Umrao Singh Sher-‐Gil Majithia Amrita Sher-‐Gil in Her

Zvara 1 Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Majithia Amrita Sher-Gil In Her Studio In Shimla, 1937 1937 Vintage Print Collection of Vivan and Navina Sundaram New Delhi, India Zvara 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I’d like to thank my incredible co-advisors, Dr. Mary Sheriff and Dr. Pika Ghosh, for providing guidance, encouragement, reassurance, and inspiration throughout this entire process. Dr. Sheriff, you are among the best professors and mentors I have ever had the pleasure of working with. It is extremely rare to find a professor who is truly devoted to the academic development of their students; you are one of the few, and I could not be more grateful. Dr. Ghosh, you have also had an enormous impact on this project by continually pushing me to ask questions, consider different perspectives, and utilize new approaches to my writing. I would also like to thank Dr. Glaire Anderson for agreeing to serve on my committee. As the first professor who encouraged me to pursue an Honors Thesis, you provided me with the initial confidence and conviction to develop a project and see it through until the very end. I would like to thank my supportive family for their participation in this process as well. To my brilliant parents, who inspire me every day to continue to grow as a student and academic: I hope you read this and it makes you proud. To my sisters, who have always been the greatest role models I could imagine: thank you for providing comforting support and comic relief whenever I needed it. -

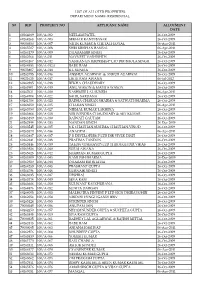

S# Rid Property No Applicant Name Allotment Date 1

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- RESIDENTIAL S# RID PROPERTY NO APPLICANT NAME ALLOTMENT DATE 1 60264689 100/A-002 NEELAM PATEL 26-Oct-2009 2 60264268 100/A-003 SEKHAR KANTI BASAK 26-Oct-2009 3 90000350 100/A-007 NITIN KUMAR & CHETALI GOYAL 06-Apr-2011 4 60265507 100/A-008 SHRI KRISHAN BANSAL 06-Apr-2011 5 60264179 100/A-009 DHARAMBIR SINGH 26-Oct-2009 6 60262564 100/A-011 NAVNEET VASHISHTH 26-Oct-2009 7 60264167 100/A-012 YASIKAN ENTERPRISES P LTD DIR BHOLA SINGH 26-Oct-2009 8 60264553 100/A-012A BABU RAM 26-Oct-2009 9 90023807 100/A-014 K L SUNEJA 26-Oct-2009 10 60265795 100/A-016 ANSHUL AGARWAL & ANKUR AGARWAL 26-Oct-2009 11 90021623 100/A-017 LIKHI RAM AWANA 06-Jul-2012 12 60262985 100/A-018 REKHA CHAUDHARY 26-Oct-2009 13 60263901 100/A-019 ANIL WASON & MAMTA WASON 26-Oct-2009 14 60267621 100/A-020 KASHMIRI LAL SUNEJA 06-Apr-2011 15 60264704 100/A-022 SAHIL SARDANA 26-Oct-2009 16 60261786 100/A-023 RADHA CHARAN SHARMA & SATWATI SHARMA 26-Oct-2009 17 60266050 100/A-025 CHARAN SINGH 06-Apr-2011 18 60263750 100/A-027 NIRMAL KUMAR LAKHINA 26-Oct-2009 19 60263868 100/A-028 VISHVENDRA CHAUDHARY & AJIT KUMAR 26-Oct-2009 20 60263189 100/A-030 RAJWATI GAUTAM 26-Oct-2009 21 60262994 100/A-033 NANDAN SINGH 26-Dec-2009 22 60263545 100/A-035 S K CHAUHAN,SUSHMA CHAUHAN,VINOD 26-Oct-2009 23 60265570 100/A-036 ANAGPAL 06-Apr-2011 24 60262887 100/A-037 P R DEVELOPERS P LTD DIR VIVEK DIXIT 26-Oct-2009 25 60262241 100/A-038 PRATIMA TANDON 26-Oct-2009 26 60263846 100/A-039 TALON VINIMAY(P) LTD THROUGH DIR.VIKAS 26-Oct-2009 27 60263926 100/A-040 -

After a Long Illness Captain Umrao Singh VC, Royal Indian Artillery Died on the 21 November 2005 at the Army Research and Referr

After a long illness Captain Umrao Singh VC, Royal Indian Artillery died on the 21 November 2005 at the Army Research and Referral Hospital, New Delhi, after a prolonged illness. He was cremated at his home village of Palra, Haryana State, on 22 November 2005. As a havildar (Sergeant) Umrao Singh was the only non-commissioned officer of either the Royal Artillery or the Indian Artillery to be awarded the Victoria Cross in the Second World War. Umrao Singh won his award for valour in what all gunners regard as their near-sacred duty - defence of their guns. By the end of 1944, General Sir William Slim's 14th Army was poised for a right-flank offensive against Lieutenant-General Sakurai Seizo's 28th Japanese Army in the coastal strip between the Irrawaddy and the Bay of Bengal. General Sir Philip Christison's XV Corps of four divisions was given the job. The offensive was launched on 12th December 1944 but fierce resistance was met by the 81st West African Division advancing down the Kaladan valley, every move forward being challenged by Japanese counter-attack. The 33 Mountain Battery, Indian Artillery, in which Havildar Umrao Singh was a field gun detachment commander, was subjected to a sustained bombardment from Japanese guns. Singh's VC citation sums up perfectly his heroic action in defending his guns against overwhelming odds. [ London Gazette, 31 May 1945 ], Kaladan Valley, Burma, 15 - 16 December 1944, Havildar Umrao Singh, Royal Indian Artillery, Indian Army “In the Kaladan Valley, Burma on 15 / 16 December 1944, Havildar Umrao Singh was in charge of one gun in an advanced section of his battery when it was subjected to heavy fire from 75 mm guns and mortars for one and a half hours prior to being attacked by two Companies of Japanese. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH THURSDAY, THE 18 SEPTEMBER,2014 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 45 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 46 TO 47 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 48 TO 62 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 63 TO 81 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 18.09.2014 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 18.09.2014 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 1. LPA 369/2014 VICNIVAAS AGENCY P SURESHAN,KAMAL SAWHNEY Vs. FOOD CORPORATOIN OF INDIA 2. LPA 371/2014 CROSS LAND MARKETING (2000) P SURESHAN,KAMAL SAWHNEY,AJIT PTE LTD PUDUSSERY Vs. THE FOOD CORPORATION OF INDIA AND ORS 3. LPA 372/2014 VICNIVAAS AGENCY P SURESHAN,MANISH SHARMA Vs. MMTC LTD 4. LPA 548/2014 WRESTLING FEDREATION OF INDIA ANUPAM DHINGRA,ANIL CM APPL. 13654/2014 Vs. SHRI JOGINDER KUMAR GROVER,MANISH MOHAN 5. LPA 549/2014 WRESTLING FEDERATION OF INDIA ANUPAM DHINGRA CM APPL. 13662/2014 Vs. SHRI RAJNEESH DALAL AND ORS 6. LPA 551/2014 WRESTLING FEDERATION OF INDIA ANUPAM DHINGRA CM APPL. 13714/2014 THROUGH ITS SECRETARY GENERAL SHRI RAJ SINGH Vs. SHRI AMIT KUMAR DHANKHAR AND ORS 7. LPA 579/2014 RESIDENTS WELFARE ASSOCIATION SURUCHII AGGARWAL CM APPL. 14528/2014 Vs. GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI AND ORS 8. W.P.(C) 6711/2013 ANIL BHATIA AND ORS. PRASHANT BHUSHAN,RANBIR CM APPL. -

Umrao Singh Designation: Associate Professor Areas of Academic Interest: Terrorism and National Security, South Asia Academic Qualification: M.A

Bio-data Name: Umrao Singh Designation: Associate Professor Areas of Academic Interest: Terrorism and National Security, South Asia Academic Qualification: M.A. Defence and Strategic Studies (Gold Medal) Ph.D. (Terrorism in Punjab: The Role of Security Forces) Teaching Experience: 15 years Research Guidance: M. Phil. dissertation 03 Ph.D. Theses 01(Degree Awarded) 02(Theses Submitted) Ph.D. Candidates Registered: 05 Address: Department of Defence and Strategic Studies, Arts Block No.6 (Second Floor), Punjabi University, Patiala 147001 09814648881(M), [email protected] Seminar Conferences organized: Seminar Coordinator, National Seminar on „India‟s National Security: Emerging Trends‟ organised by Department of Defence & Strategic Studies, Pbi. Uni. Patiala (10-11 March, 2010) Coordinator, Panel Discussion on „Security Environment in South Asia: Emerging Trends‟ organised by Department of Defence & Strategic Studies, Pbi. Uni. Patiala in collaboration with Association of Asia Scholars, New Delhi (22nd November 2010) Organising Secretary Intenational conference on „Peace, Security and Economic Development in South Asia organised by Department of Defence & Strategic Studies, Pbi. Uni. Patiala in collaboration with Association of Asia Scholars, New Delhi (4-6 March, 2011) Seminar Director National Seminar on the theme “India‟s National Security: Challenges and Responses” Organised by Department of Defence & Strategic Studies, Pbi. Uni. Patiala 17 February, 2016 Seminar/conferences/ Workshops Presentations: International 08 National 14 Invited Lectures 25(Disaster management in India) Research Project Completed: 01 (In collaboration) Publications Security and Development: Nehruvian Perspective in Ranjit Singh Ghuman and Indervir Singh Eds. (2014) Nehruvian Economic Philosophy And Its Contemporary Relevance pp. 137-148 ISBN: 978-81-85835-70-5 Geopolitics of Energy Security in the Bay of Bengal: Maritime Strategies of India and China MALAYSIAN JOURNAL OF TROPICAL GEOGRAPHY Volume. -

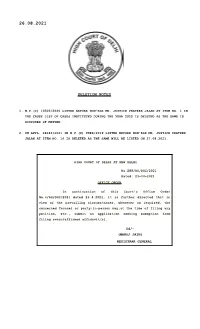

Deletion Notes

26.08.2021 DELETION NOTES 1. W.P.(C) 10505/2020 LISTED BEFORE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PRATEEK JALAN AT ITEM NO. 1 IN THE CAUSE LIST OF CASES INSTITUTED DURING THE YEAR 2020 IS DELETED AS THE SAME IS DISPOSED OF MATTER. 2. CM APPL. 28242/2021 IN W.P.(C) 9986/2019 LISTED BEFORE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PRATEEK JALAN AT ITEM NO. 16 IS DELETED AS THE SAME WILL BE LISTED ON 27.08.2021. HIGH COURT OF DELHI AT NEW DELHI No.289/RG/DHC/2021 Dated: 23-04-2021 O FFICE ORD ER In continuation of this Court's Office Order No.4/RG/DHC/2021 dated 23.4.2021, it is further directed that in view of the prevailing circumstances, wherever so required, the concerned Counsel or party-in-person may,at the time of filing any petition, etc., submit an application seeking exemption from filing sworn/affirmed affidavit(s). Sd/- (MANOJ JAIN) REGISTRAR GENERAL As approved by Hon'ble Chairman, DHCLSC, National Lok Adalat is to be held on 11.09.2021(SECOND SATURDAY) at High Court of Delhi for pending cases under following category:- 1. Criminal Compoundable Offence 2. NI Act cases under Section 138; 3. Bank Recovery cases; 4. MACT cases; 5. Labour disputes cases; 6. Electricity and Water Bills[excluding non-compoundable] 7. Matrimonial disputes; 8. Land Acquisition cases; 9. Services matters relating to pay and allowances and retiral benefits; 10. Revenue cases; 11. Other civil cases(rent, easmentary rights, injunction suits, specific performance suits) etc; To facilitate settlements, DHCLSC will conduct on line Pre-Lok Adalat sittings w.e.f. -

© 2017 Irina Spector-Marks

© 2017 Irina Spector-Marks CIRCUITS OF IMPERIAL CITIZENSHIP: INDIAN PRINT CULTURE AND THE POLITICS OF RACE, 1890-1914 BY IRINA SPECTOR-MARKS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Antoinette Burton, Chair Associate Professor Teresa Barnes Associate Professor James Brennan Professor Isabel Hofmeyr, University of Witswatersand Associate Professor Dana Rabin Abstract At the turn of the twentieth century, Indian immigrants throughout the British empire faced a rise in discriminatory legislation. They responded by asserting that as imperial citizens, Indians should be treated equally with white British subjects. Although imperial citizenship had no fixed legal meaning, Indian activists invoked imperial citizenship as a legal status and as an identity that carried racial and civilizational overtones. Through a close reading of iterations of imperial citizenship across a wide range of print culture sources, I show how imperial citizenship, although ostensibly race-blind, was an implicitly racialized discourse. Based on research from archives in Ottawa, Vancouver, Durban, Pietermaritzburg, Pretoria, and London, I map how the discourse of imperial citizenship circulated across the empire in a transnational print sphere of periodicals, pamphlets, and petitions. By focusing on the work of activists in Canada and South Africa, I explore the ways in which local political and racial contexts precluded the potential for material forms of transnational collaboration. My dissertation nuances the “transnational turn” in the humanities by emphasizing the role of local factors in shaping larger global politics. -

General Knowledge

General Knowledge General Knowledge Question Answers For Bank PO Exams 1.Who is the new Prime Minister of Hungry ? (A) Victor Orban (B) Gorden Bajnai (C) Jeno Fock (D) Ference Gyurcsany Answer: Gorden Bajnai 2.Who is the new prime minister of Denmark ? (A) Anders Fogh Rasmussen (B) Lars Looke Rasmussen (C) Poul Nyrup Rasmussen (D) Poul Hartling Answer: Lars Looke Rasmussen 3.Who is the Author of the book “My China Diary” (A)Kanwal Sibal (B)Salman Haider (C)J.N. Dixit (D)Natwar Singh Answer: Natwar Singh 4.Umrao Singh has passed away recently .Which of the following field was he associated with ? (A) Film (B) Journalism (C) Sports (D) Politics Answer: Sports 5.Vidya Pillai is related to which sport ? (A) Snooker (B) Golf (C) Archery (D) Billiards Answer: Snooker 6.Who has become the first Indian to win two medal in a Shooting World Cup? (A) Gagan Narang (B) Sanjeev Bindra (C) Abhinav Bindra (D) Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore Answer: Gagan Narang 7.Which country has launched a navigational Satellite? (A) South Korea (B) North Korea (C) India (D) China Answer: China 8.Where will be held the Final of the Cricket World Cup 2011? (A)Colombo (B)Mumbai (C)New Delhi (D)Dhaka Answer: Mumbai 9.When is the Commonwealth Day celebrated? (A) May 1 (B) May 3 (C) May 15 (D) May 24 Answer: May 15 10.What is the full form of PTC ? (A) Public Transport Certificate (B) Pubic Telecommunications Council (C) Products Through Consumer (D) Pass Through Certificate Answer: Pass Through Certificate 1. -

Contribution of the Indian Armed Forces to the Second World War: Book Release and Panel Discussion IDSA Special Feature 1

IDSA Special Feature January 2013 Contribution of the Indian Armed Forces to the Second World War: Book Release and Panel Discussion IDSA Special Feature 1 Contents Welcome Remarks................................................................................................................ 2 Arvind Gupta Writing the History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War: A Brief Overview............................................................................................................................... 4 History Division, Ministry of Defence, Government of India Keynote Address.................................................................................................................. 5 JFR Jacob Panel Discussion Opening Remarks.......................................................................................................... 12 Satish Nambiar Campaign in South East Asia 1941-42 and The Arakan Operations 1942-45.......... 14 Y.M. Bammi Campaign in Western Asia......................................................................................... 23 Rahul K. Bhonsle The East African Campaign 1940-41 and The North African Campaign 1940-43........................................................................................................ 27 P.K. Gautam Explore the Socio-Economic Impact of the Second World War.............................. 33 U.P. Thapliyal Reclaiming Our Legacy............................................................................................... 35 RTS Chhina Summaries of the Eight -

Director/Propriter/Partner Office Mobile No

LICENSE LICENSE VALID S.No. AGENCY NAME Director/Propriter/Partner Office Mobile No. LICENCE AREA L. NO. Off-Distt. ISSUED UP TO DESERT HAWK EX-SERVICEMEN Raghuveer Singh A-6, Vinobha Bhave 2350332, 1 WELFARE CO-OPRETIVE B-78,Vinobha Bhave Nagar,Vaishali Nagar,Vaishali Nagar, All Rajasthan 1/STATE 17.03.2007 16.03.2022 Jaipur 2359257 SOCIETY LTD. Nagar,Jaipur Jaipur MARU PRAHRI SEVA NIVRAT Zor Singh SURKSHA BAL SAINIK Nehru Nagar , Barmer 222052, Barmer, Jaisalmer, 2 INVESTIGATION WELFARE CO- Nehru Nagar , Barmer 10/STATE 19.06.2007 18.6.2022 Barmer 9414755889 Jalore, Jodhpur, Pali PORETIVE SOCIETY LTD. BARMER BHILWARA ZILA EX- Umrao Singh Rathore Ashok Leyland Chraha, 3 SERVICEMEN WELFARE 36-1,Babu Nagar, Bhilwara. 2244202 All Rajasthan 12/STATE 25.06.2007 24.6.2022 Bhilwara Pur Road, Bhilwara SAHKARI SAMITI LTD. CHITTORGARH EX-SERVICEMEN Gheesu Lal Khatik 62, Pratap Nagar, 2244203, 4 WELFARE CO-OPRETIVE 10-E-56,Tilak Nagar,Bhilwara All Rajasthan 13/STATE 25.06.2007 24.6.2022 Chittorgarh Chittorgarh 9829517418 SOCIETY LTD. Satya Narayan Pareek 5 RELIANCE SECURITY SERVICES Pur Road, Bhilwara 9414113217 All Rajasthan 21/STATE 30.07.2007 29.7.2022 Bhilwara 66, Subhash Nagar, Bhilwara Jagdish Prasad Sharma KUMBHJI DARBAR SECURITY E-52 A, Prem Nagar, 2342556, Jaipur, Tonk, Jodhpur, 6 E-73, Prem Nagar, Jhotwara, Jaipur. 22/STATE/ 06.08.2007 05.08.2022 Jaipur SERVICES Jhotwara, Jaipur 9928300117 Alwar, Udaipur Ramesh Pimple 022-26396050, CENTRAL INVESTIGATION & 102-A, Panchmukh Panch, Andheri 46, Vallabh Nagar Ext. 7 9821109295, All Rajasthan 28/STATE 03.09.2007 2.9.2022 Kota SECURITY SERVICE LTD. -

Chaucer Auctions Internet Only

Chaucer Auctions Internet Only . Autograph Auction, Autographs, First Day Covers, Military . Started 12 Jun 2015 10:00 BST United Kingdom Lot Description Donitz & Speer. Great Admiral Karl Donitz who Commanded the U-Boat Fleet and Professor Albert Speer who was a German Architect 1 and Armour Organiser during National Socialism both Signed RAF Viscount Portal FDC. Good condition £40-60 2 Arthur Harris signed on his own historic aviators covers. Good condition £30-40 3 Brian Trubshaw signed 1974 rare Concorde 202 Middle and Far East Development flight cover. Good condition £30-40 James Hunt signed Benham 1982 Motor Cars official FDC, BLS3. Former F1 World Champion Motor Racing driver. Good condition £60- 4 80 5 Sir Tom Sopwith signed on his own test pilot cover. Good condition £30-40 6 Vera Lynn, Ian Fraser VC, Earl Haig signed 2000 Ex-Prisoner of War Association cover. Good condition £20-30 William Hartnell Dr Who Small page taken from an autograph book bearing the dedicated autograph of William Hartnell (1908-1974), 7 who is of course best known for playing the first incarnation of the Doctor in Doctor Who from 1963-1966. Incredibly rare: we have seen photos for sale for £1500. Good con ...[more] Patrick Troughton Dr Who Small page taken from an autograph book with inset photo, bearing the undedicated autograph of Patrick 8 Troughton (1920-1987), who is of course best known for playing the second incarnation of the Doctor in Doctor Who from 1966-1969. Incredibly rare: we have seen photos for s ...[more] SHELBURNE, 2nd Earl of (1737-1805) 1st Marquess of Lansdowne; British Prime Minister 1782-1783. -

Name Place Category Number Abdul Azeem Jaffer

NAME PLACE CATEGORY NUMBER ABDUL AZEEM JAFFER BENGALURU FULL A 001 ABDUL AZEEZ A V KOZHIKODE FULL A 002 ABDUL FATAH BELLARY ASSOCIATE A 003 ABDUL MAJID ADIL HYDERABAD FULL A 004 ABHAY ANAND CALICUT FULL A 005 ABHIJITH S.M KARNATAKA FULL A 006 ABHIMAN GAUTAM THENI FULL A 007 ABHISHEK BHAT CHENNAI ASSOCIATE A 008 ABIJIT SHETTY UDUPI ASSOCIATE A 009 ABRAHAM KURIEN NADIAD AFFILIATE A 010 ABY MADAN THIRUVANANTHAPURAM FULL A 011 ADITYA SHENOY PAYYANUR ASSOCIATE A 012 ADVE NAGARAJ RAO BENGALURU FULL A 013 AFTABHUSSAIN HYDERABAD FULL A 014 AGISH M A THIRUVANANTHAPURAM FULL A 015 AJAY KUMAR BIHAR AFFILIATE A 016 AJAY KUMAR GUNTAKA VIJAYAWADA FULL A 017 AJIT J THOMAS PATHANAMTHITTA FULL A 018 AJITH BHARATHAN KOLLAM FULL A 019 AJUMAL S S FULL A 020 AKASAPU BHAGAVAN HYDERABAD FULL A 021 AKULA VENKATA KRISHNA KISHORE VIJAYAWADA FULL A 022 ALAGAPPAN C TRICHY FULL A 023 ALBERT A S KOTTAYAM FULL A 024 ALI POONAWALA BENGALURU FULL A 025 ALI REZA FAZAL KOLKATTA AFFILIATE A 026 ALISHAHID KHAN HYDERABAD FULL A 027 ALTHAF HUSSAIN K. ANDHRA PRADESH ASSOCIATE A 028 AMAR NEEDHI GANESAN B MALAI FULL A 029 AMARKUMAR JAYARAM BENGALURU FULL A 030 AMEY YASHWANT PATIL MAHARASHTRA ASSOCIATE A 031 AMISH KIRANBHAI MEHTA GUJARAT FULL A 032 AMIT GOUR JABALPUR AFFILIATE A 033 AMIT K BHOIR KOZHIKODE ASSOCIATE A 034 AMIT KATTI BELGAUM ASSOCIATE A 035 AMIT KUMAR MYSURU FULL A 036 AMIT KUMAR NELLORE, ODISHA ASSOCIATE A 037 AMIT M MUNGARWADI BELGAUM FULL A 038 AMIT VIJAY DESHPANDE VELLORE ASSOCIATE A 039 AMITAVA M VELLORE FULL A 040 AMITH CHANDRA K.M KANNUR ASSOCIATE A 041 AMOLKUMAR