2000 Final Pacific Coastal Barriers Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People, Paws & Partnerships

20 IMPACT REPORT People, Paws & 20 Partnerships ABOUT HELPING PAWS OUR MISSION The mission of Helping Paws is to further people’s independence and quality of life through the use of Assistance Dogs. The human/animal bond is the foundation of Helping Paws. We celebrate the mutually beneficial and dynamic relationship between people and animals, honoring the dignity and well-being of all. ASSISTANCE DOGS INTERNATIONAL MEMBER Helping Paws is an accredited member of Assistance Dogs International (ADI). We adhere to their requirements in training our service dogs. ADI works to improve the areas of training, placement and utilization of assistance dogs as well as staff and volunteer education. For more information on ADI, visit their website at www.assistancedogsinternational.org. BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND INSTRUCTORS DIRECTORS DIRECTORS OFFICERS Pam Anderson, Director of Development Ryan Evers – President Eileen Bohn, Director of Programs Kathleen Statler – Vice President STAFF James Ryan – Treasurer Chelsey Bosak, Programs Department Administrative Coordinator Andrea Shealy – Secretary Judy Campbell, Foster Home Coordinator and Instructor MEMBERS Laura Gentry, Canine Care Coordinator and Instructor Ashley Groshek Brenda Hawley, Volunteer and Social Media Coordinator Judy Hovanes Sue Kliewer, Client Services Coordinator and Instructor Mike Hogan Jonathan Kramer, Communications and Special Projects Coordinator Alison Lienau Judy Michurski, Veteran Program Coordinator and Breeding Reid Mason Program Coordinator Kathleen Statler Jill Rovner, Development -

Shelby STATE of ALABAMA-DEPARTMENT of REVENUE-PROPERTY TAX DIVISION PAGE NO: 1 TRANSCRIPT of TAX DELINQUENT LAND AVAILABLE for SALE DATE: 9/24/2021

2753 Shelby STATE OF ALABAMA-DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE-PROPERTY TAX DIVISION PAGE NO: 1 TRANSCRIPT OF TAX DELINQUENT LAND AVAILABLE FOR SALE DATE: 9/24/2021 Name CO. YR. C/S# CLASS CODE PARCEL ID DESCRIPTION AV Amt Bid at Tax Sale BRANTLEY HOMES INC 58 00 0019 2 2 5814093130011420000000 WEATHERLY WARWICK VILLAGE SEC 17 PH 2 AMENDED ACR 4000 277.85 EAGE S31 T20S R02W MB022 PG067 DIM 55.29 X 32.57 SCOTT & WILLIAMS CO INC 58 00 0190 2 6 5813082710010020000000 BEG NE COR LOT 78 LAUREL WOODS PHASE III MB17 PG9 19200 966.19 6 W 63.91 N W126 E225 SW62.75 S100(S) TO POB S27 T CANYON PARK PARTNERSHIP 58 01 0025 2 8 5813061320040760000000 BEG SW COR LOT 14 CANYON PK TW NHMES MB19 PG19; NE 6800 486.57 266.19 TO S ROW CANYON PK DR, SW164.81 SLY169.43 E CARSON KARL JR & JANICE R 58 01 0026 3 1 5836030840020050000000 BEG NW COR LOT 4 BLK 1 G A NAB ORS SE 300 SW 120. 5820 325.03 8 NW 300 NE120.8 TO POB S08 T24N R12E AC .83 SQ FT DAVIDSON JOHN E 58 01 0040 2 1 5810020300010030000000 COMM NE COR NW1/4 S3T19R2W S520'S TO NLY RIVER BA 3000 202.50 NK POB N & WLY 1370'(S) TO 1/4 1/4 LN N 90'(S) E 8 DAVIDSON JOHN E 58 01 0045 2 1 5810041700010090010000 SW COR NW1/4 SW1/4, N301.85 TO POB; CONT N78 TO C 3000 208.20 /L CAHABA RIVER, NE ALG C/L RIVER 325.13, SW380.9 FOREST PARKS LLC 58 01 0064 2 1 5809052100000012350000 FOREST PARKS 6TH SECTOR 2ND PHASE MB 24 PG 110 LO 9000 471.15 T 615 S21 T19S R01W LOT DIM 114.90 BY 158.58 ACRES HAYES ADELINE 58 01 0078 3 7 5827041930010230000000 ALDRICH TOWN OF THOMAS ADDITION 82' X N 41' OF LO 1200 118.77 T 3 BLK 8 S19 T22S R03W MB003 PG052 LOT DIM 41 .00 KENT FARMS PARTNERSHIP 58 01 0101 2 2 5823011130020260000000 BEG INTER N ROW CO ROW HWY 26 & E ROW DOUGLAS DR 3600 290.82 E139.79 NW 330.73 TO W LN SEC 11 S ALG SEC LN 275 SUMMER BROOK PARTNERSHIP 58 01 0185 2 2 5823011120030130000000 BEG SE COR LOT 107 SUMMER BROOK SEC 5 PH 7 MB23 P 2120 186.95 G49; SE97.52 N360.66 N65 W188(S) S362.66 TO POB. -

IN the UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT for the EASTERN DISTRICT of VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) in Re

Case 21-30209-KRH Doc 349 Filed 03/26/21 Entered 03/26/21 21:03:19 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 172 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) ALPHA MEDIA HOLDINGS LLC, et al.,1 ) Case No. 21-30209 (KRH) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Julian A. Del Toro, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned cases. On March 15, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: • Notice of Filing of Plan Supplement (Docket No. 296) Furthermore, on March 15, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C: • Notice of Filing of Plan Supplement (Docket No. 296 – Notice Only) Dated: March 26, 2021 /s/Julian A. Del Toro Julian A. Del Toro STRETTO 410 Exchange, Suite 100 Irvine, CA 92602 Telephone: 855-395-0761 Email: [email protected] 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases, along with the last four digits of each debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Alpha Media Holdings LLC (3634), Alpha Media USA LLC (9105), Alpha 3E Corporation (0912), Alpha Media LLC (5950), Alpha 3E Holding Corporation (9792), Alpha Media Licensee LLC (0894), Alpha Media Communications Inc. -

Plaintiffs' Counsel Has Stated That Plaintiffs Will Oppose This Motion. in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT O

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ ) ELOUISE PEPION COBELL, et al.,) ) No. 1:96CV01285 Plaintiffs, ) (Judge Robertson) v. ) ) DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary of ) the Interior, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) DEFENDANTS’ MOTION IN LIMINE TO EXCLUDE ALL EXHIBITS AND PROPOSED TESTIMONY IDENTIFIED IN PLAINTIFFS’ PRETRIAL STATEMENT THAT ARE OUTSIDE THE SCOPE OF MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED AT THE OCTOBER 10, 2007 TRIAL Pursuant to Rule 104(a) of the Federal Rules of Evidence, Defendants respectfully move this Court for an order in limine excluding all exhibits and proposed testimony identified in Plaintiffs’ Pretrial Statement that are related to matters outside the scope of the October 10, 2007 trial.1 Plaintiffs have listed 4435 exhibits, the majority of which involve disparate and irrelevant subjects such as IT security, asset management activities and other topics far afield from accounting issues. In their Pretrial Statement, Plaintiffs also identify 53 proposed witnesses (while reserving the right to call an untold number of unidentified witnesses from “corporate entities”), and designate the testimony from prior proceedings of 53 witnesses, most of which would be offered on the same irrelevant topics. Defendants seek an order in limine to exclude such proposed irrelevant evidence for the reasons set forth below. 1/ Plaintiffs’ counsel has stated that Plaintiffs will oppose this motion. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to Rule 16 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, this Court is authorized to conduct pretrial conferences “for such purposes as . discouraging wasteful pretrial activities [and] improving the quality of the trial through more thorough preparation.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 16(a)(3)-(4). -

ICHS Success Stories

ICHS Success Stories We have had hundreds of success stories here at I.C.H.S. Stories of lost pets finding a new loving forever home! On these pages we would like to share a few of these stories with you. If you have adopted a pet from I.C.H.S. and would like to share your story, please contact us. Never Give Up Hope! Yesterday was one of those days that we all dream about a miracle day! And it was all because of a senior dog named Lucky. Toffee, alias Lucky, had been hanging around the ICHS shelter since August 2012 when he arrived as a stray. This awesome little dog had been charming everyone he met but was still searching for his forever home. Since November is National Adopt a Senior Pet Month, we decided that he was the perfect spokes dog for our Pet of the Week appearance on Channel 15’s Morning Show. He was an absolute star and we were sure hoping that he would finally get the home that he so richly deserved. Imagine our surprise when only 30 minutes after the show, there was a voice mail on the ICHS answering machine from someone claiming to be Toffee’s long-lost owner! But it was true!!! Toffee’s real name was Lucky and he had been missing for 4 years after getting loose. His family had spent months looking for him without success and had resigned themselves to the worst nightmare that a pet owner can have, that their beloved pet who had lived with them since his birth was irretrievably gone forever! They couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw Lucky on Channel 15. -

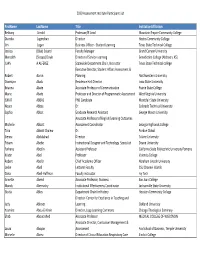

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

Dogs for the Deaf, Inc. Assistance Dogs International

Canine Listener Robin Dickson, Pres./CEO Fed. Tax ID #93-0681311 Spring 2011 • NO. 116 Dear Dogs for the Deaf Family, On June 16, 1981, Robin Dickson began working for Dogs for the Deaf. She began as a Trainer Apprentice, became a Certified Audio Canine Trainer, then Assistant Director, and President/CEO. For 30 years Robin has worked non-stop for this wonderful organization. As our President and CEO, she has nurtured what was, in 1981, a very small organization into one of the top (and most respected) Assistance Dog programs in the country. Robin has touched a lot of lives during those years, made countless friends, and played a key role in saving thousands of dogs from some very uncertain futures. The Staff and Board of Directors at Dogs for the Deaf want to publicly thank Robin Dickson for 30 years of service. Congratulations, Robin, on your 30th Anniversary at Dogs for the Deaf! We will never be able to thank you enough for your faithful leadership, but we would certainly like to try during the next 30 years! Sincerely, Marvin Rhodes Robin and Bonsai DFD Board of Directors Chair P.S. We would like to make a Book of Remembrance for Robin and encourage you to send a note of congratulations or a special DFD memory to DFD by June 15. We will put all the notes into the book and present it to Robin. GREATEST GIFT Our friends at Ram Offset Lithogra- March 3, 2011 phers have graciously donated the full color pages in this newsletter. Dear Robin, Ram is a full service, large, commer- The greatest gift I ever received is my Hearing Dog cial printer in the Southern Oregon from Dogs for the Deaf. -

Royal Army Veterinary Corps

Royal Army Veterinary Corps The Royal Army Veterinary Corps (RAVC), known as the Army Veterinary Royal Army Veterinary Corps Corps (AVC) until it gained the royal prefix on 27 November 1918, is an administrative and operational branch of the British Army responsible for the provision, training and care of animals. It is a small corps, forming part of the Army Medical Services. Contents History Function Structure Honours Memorials Heads of the Corps Cap badge of the Royal Army Order of precedence Veterinary Corps incorporating References Chiron Further reading Active 1796–present External links Country United Kingdom History Allegiance British Army Role Animal Healthcare The original Army Veterinary Service (Veterinary Corps) Garrison/HQ Defence Animal within the Army Medical Training Regiment, Department was founded in Melton Mowbray, 1796 after public outrage Leicestershire concerning the death of Army Nickname(s) RAVC horses. John Shipp was the first March Drink Puppy Drink / veterinary surgeon to be A-Hunting We Will commissioned into the British Go (Quick); Golden Army when he joined the 11th Spurs (Slow) Light Dragoons on 25 June [1] Equipment Dogs, horses A sergeant of the RAVC bandages 1796. the wounded ear of a mine-detecting Commanders dog at Bayeux in Normandy, 5 July The Honorary Colonel-in-Chief Colonel-in- The Princess Royal 1944 is the Princess Royal who has Chief visited RAVC dog-handling Insignia units serving in Afghanistan.[2] Tactical Recognition Flash In late March 2016, the Ministry of Defence announced that Fitz Wygram House, one of the Corps' sites, was one of ten that would be sold in order to reduce the size of the Defence estate.[3] Function The RAVC provides, trains and cares for mainly dogs and horses, but also tends to the various regimental mascots in the army, which range from goats to an antelope. -

MILITARY STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS for USE on DRAWINGS, and in Specifications, STANDARDS and TECHNICAL DOCUMENTS

MIL-STD-12D29 May 1981 SUPERSEDING MIL-STD-l2C 15 June 1968 MILITARY STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS FOR USE ON DRAWINGS, AND IN SPECIFICATiONS, STANDARDS AND TECHNICAL DOCUMENTS NO DELIVERABLE DATA REQUIRED BY THIS DOCUMENT naD■ r u .. , .. I I www.ExpressCorp.com HIL-STD-12D 29 Hay 1981 Uf,;t"AKTM.t.NT UI'- DE.l'�NSE Washington, D. C. 20301 Abbreviations for use on Drawings, and in Speciiications, Standards and Tech aical Documents. MIL-STD-12D 1. This Miiitary Standard is approved for use by all Depar�men�s and Agencies of the Department of Defense. 2. Beneficial comments (recommendations, additions, deletions) and any pertinent data which may be of use in improving this document should be addressed to: Cotn1nander, US Army Armament Research and Develapiiiei'it Coiiiiiiand, ATTN: DRDAR-TST-S, Dover, New Jersey 07801, by using the self-addressed Standardization Document Improvement Proposal (DD Form 1426).appearing at the end of this document or by letter. 11 MIL-STD-12D 29 May 1981 CONTENTS Paragraph Page 1 SCOPE------------------------------------------------------ 1 1.1 ---r-s�nne 1 1.2 Application -------------------- 1 1. 2 .1 Shortwo rds--------------------- l 1.2.2 Field of u se-�------------------ l 1.2. 3 Combining fonn ------------------ l REFERENCED DOCUMENTS-------------- 1 2. 1 General ------------------------ 1 2.2 Standards ----------------------- l 2.3 Other publications-------------- 2 3 DEFINITIONS ---------------------- 2 3. i Abbreviations -------=-=====e===- 2 4 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS-------------- 2 4.1 Clarity ------------------------- 2 4.2 Word combinations --------------- 2 4.3 Syntax ---------------------�---- 2 4.4 Capitalization------------------ 4.5" ,:. Punctuation --------------------- 2 ...o ·Revised abbreviations ----------- 2 4.7 Syrrt,ols ------------------------- 3 4.8 Abbreviations used in existing technical documents---------- 3 5 DETAIL REQUIREMENTS-------------- 3 5. -

![Pets + the People Who Love Them | Spring 2016 [FROM the CEO] an Amazing Journey](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5776/pets-the-people-who-love-them-spring-2016-from-the-ceo-an-amazing-journey-3085776.webp)

Pets + the People Who Love Them | Spring 2016 [FROM the CEO] an Amazing Journey

TAIL’STALES Pets + The people who love them | Spring 2016 [FROM THE CEO] An amazing journey... This is my last note in the newsletter. I will help every single soul who finds their way to be retiring soon. The date will be determined our doors. by the arrival of my replacement. And the volunteers are with us at every I have been in the animal welfare world turn. They are here every single day of the for more than a quarter of a century, with year, regardless of the weather, the time or the last 18 at the Nebraska the day. They make sure every possible dog Humane Society. It has is walked, petted and loved. They provide been an amazing journey. I foster care for those in need of healing have witnessed wonderful prior to adoption. They help care for all the people with hearts the size animals at the shelter, as well as help adopt of the state; people who will them into loving homes. Our volunteers do anything and everything touch every aspect of the shelter. possible to help animals Last, but surely not least, is Friends and who feel that our companion animals Forever. This wonderful, generous and deserve to live in an environment free of compassionate group was formed before I fear and pain. arrived at NHS. They are our partners. We Great things have been accomplished by would not be where we are without these all of these folks. amazing women who make time in their Because of the generosity of Omaha, we busy lives to make a difference for the have grown from a small, inadequate, run- animals. -

Page No: 1 Date

2753 STATE OF ALABAMA-DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE-PROPERTY TAX DIVISION PAGE NO: 1 TRANSCRIPT OF TAX DELINQUENT LAND AVAILABLE FOR SALE DATE: 9/24/2021 Name CO. YR. C/S# CLASS CODE PARCEL ID DESCRIPTION AV Amt Bid at Tax Sale MCHUGH ALICE H 31 00 0028 2 13 3110083330001890000000 H\S BASE YEAR LT 3 BLK 3 COOSA LAND CO N 10TH ST A 2740 194.63 DD PLAT B-373 GADSDEN SEC 33 TWP 11S R 6E BK 1223 STRONG ROBERT HIRAM 31 00 0070 2 13 3115011130000390000000 H/S BASE YEAR - LOT 18 BLK B GADSDEN LAND & BUILD 680 84.65 ING CORP SUB PLAT C ALLEN BOBBY M & BETTY K 31 00 0079 2 13 3115011140000840000000 H/S BASE YEAR - LOTS 23,24&25 BLK G J.C. SIZEMORE 6640 393.37 FIRST ADD TO OAKVIEW PLAT C-71 GADSDEN SEC 11 TWP LOVEJOY MYRTLE EST OF 31 00 0097 2 13 3115020420001690000000 H/S BASE YEAR - BEG 170'(S) N OF INT N ROW AVE H 3820 249.67 & E ROW EVANS ST TH G A D HOUSES INC 31 00 0121 2 13 3115030540002780000000 H/S BASE YEAR LOT 15 BLK 20 GADSDEN LAND & IMP CO 3280 222.15 PLAT A-23 GADSDEN SEC 5 TWP 12S R 6E BK 1060 PG 4 TOMLIN YVONNE & ANNA WILLIAMS 31 00 0128 2 13 3115030540003610000000 H/S BASE YR N 60' LT 7 HILL & CANSLER ADD PLAT A- 20 51.02 74,75 5-12-6 GORDON SHELIA M & JACKIE 31 00 0173 2 13 3115061410003250000000 H/S BASE YEAR LTS 11-12 BLK 1 BROWN'S ADD C-95 GA 300 65.29 DSDEN PENDERGRASS CLIFTON E & SUE B 31 00 0194 2 13 3116010140000560000000 H/S BASE YEAR - LOT 25 BLK 10 WALNUT PARK ADD PLA 460 73.44 T B 117 GADSDEN PILGRIM CATHERINE D 31 00 0199 3 13 3116010140003310000000 H/S BASE YEAR LOTS 21-22-23 BLK 11 WALNUT PARK AD 3040 209.92 D PLAT B 117 -

Cry Havoc Provides a Fascinating Insight Into the History of Dogs and Their Current-Day Employment

CRY HAVO C The History of War Dogs h CRY HAVO C The History of War Dogs h Nigel Allsopp h FOREWORD I have lost count of the number of books I have read on training dogs, together with numerous dog anecdotes, over the past forty years. My keen interest in dogs started in 1970 when I was posted to the United States Army Scout Dog School at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. I was the first commander of the Explosive Detection Dog Wing at the Army Engineers School of Military Engineering (SME), Moorebank, near Sydney in Australia. I recruited all the dogs and handlers, and commenced training the dogs for service in the War of South Vietnam. In those days we were called the Mine Dog Wing. The engineer mine dog teams did not go to Vietnam because, just as we were packing to go there in 1972, Australia withdrew from the war. That started a lifetime of fascination about the capabilities and uses of military working dogs. I commenced a military dog breeding program at the SME with technical support from the Commonwealth Scientific Industrial and Research Organisation (CSIRO) on the genetics of our program. We started training the pups in the detection of explosives from the age of three weeks. Every person in my training team of engineer ‘doggies’ was amazed by the capacity of the dogs to learn new behaviours and search requirements so quickly. We realised that we were only scratching the surface of their capabilities and uses. I needed to know more about the history of military working dogs.