Developing Bowen Island's Crippen Regional Park, 1978-2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water for Our Island Community

WWaatteerr ffoorr oouurr iissllaanndd ccoommmmuunniittyy MountMount Gardner Tunstall Gardner (727 metres) Bay Josephine Lake Grafton Lake Honeymoon Killarney Lake Lake Seymour Bay Eagle Cliff Snug reservoir Cove Aerial map image of Bowen Island, viewed looking to southwest, created by draping a mosaic of aerial photographs over a digital elevation model. Image created by Ryan Grant. Geological Survey of Canada Miscellaneous Report 88, 2005 By: Bob Turner, Richard Franklin, Murray Journeay, David Hocking, Anne Franc de Ferriere, Andre Chollat, Julian Dunster, Alan Whitehead, and D. G. Blair-Whitehead. Advisory Committee: Stacey Beamer, D. G. Blair-Whitehead, Ross Carter, Andre Chollat, Julian Dunster, Anne Franc de Ferriere, Bill Hamilton, Ian Henley, Dave Hocking, Will Husby, Murray Journeay, Denison Mears, John Reid, Mallory Smith, Ian Thomson, Bob Turner, Dick Underhill, Alan Whitehead, Dave Wrinch, Dave Yeager. Natural Resources Ressources naturelles Canada Canada BOWEN ISLAND c Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2005 Hi, I'm Raindrop. Come with me and explore the story of water on Bowen Island. BOWEN ISLAND We are a small island surrounded by salty ocean water, and so there are limits to our freshwater supply. Yet all life - people, other animals and plants - rely utterly on a continued supply. So we need to answer important questions: Do we have enough water? Are we using it wisely? Are we protecting our drinking water supplies? Are we leaving Bowen enough for nature? Island Vancouver Pacific Victoria Ocean MountMount Gardner Tunstall Gardner (727 metres) Bay Seattle Josephine Lake Grafton Lake Honeymoon Killarney Lake Lake Seymour Bay Eagle Cliff Snug reservoir Cove 1 Watershed c by Pauline Le Bel 2002 Water Restless Water shed singing the shore pebbles since the beginning; dancing the moon silver beads of life how we long to contain you. -

A Bowen Island Case Study

DWELLING, TOURISM AND SUSTAINABILITY ON THE RURAL- URBAN FRINGE: A BOWEN ISLAND CASE STUDY by Donna Nona Pettipas BFA, University of Victoria, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Resource Management and Environmental Studies) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) January, 2010 © Donna Nona Pettipas, 2010 ABSTRACT The thesis examines the question of why people live in rural communities, what draws them to these communities and the significance of social sustainability. The focus is on the view of individual perspectives that could be obtained through the process of completed questionnaires and interviews. Results of the combined questionnaire and interviews were referenced to earlier studies and to government statistics. The community of Bowen Island served as the case study, a rural community with a historical and evolving relationship to Metro Vancouver, British Columbia. The research activity was designed to be one of information and knowledge gathering, rather than an issue-oriented approach. The approach taken is one of discovering patterns of shared values and the adaptive practices of islanders in their homes and community environs. Transcribed interview responses were grouped by enquiry type to facilitate comparison between participants across BI neighbourhoods, resulting in qualitatively rich personal narratives about home, habitat and community engagement. The community is physically engaged in a beautiful mountainous and marine environment, which is also a tourist destination. Fun is a quality of BI‘s community celebrations along with spirituality and a connection to nature, the backdrop to a privileged life-style; some with ‗plenty of dough‘ most somewhere in-between ranging to bohemian artists, sharing in the community dynamic. -

IDP-List-2012.Pdf

INFANT DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Revised January 2012 Website: www.idpofbc.ca 1 Contact information for each Program including addresses and telephone numbers is listed on the pages noted below. This information is also available on our website: www.idpofbc.ca *Aboriginal Infant Development Program Pages 2-3 VANCOUVER COASTAL REGION Vancouver Sheway Richmond *So-Sah-Latch Health & Family Centre, N Vancouver North Shore Sea to Sky, Squamish Burnaby Sunshine Coast, Sechelt New Westminster Powell River Coquitlam *Bella Coola Ridge Meadows, Maple Ridge Pages 4-5 FRASER REGION Delta *Kla-how-eya, Surrey Surrey/White Rock Upper Fraser Valley Langley Pages 6-8 VANCOUVER ISLAND REGION Victoria * Laichwiltach Family Life Society *South Vancouver Island AIDP *Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Gold River Cowichan Valley, Duncan *‘Namgis First Nation, Alert Bay *Tsewultun Health Centre, Duncan *Quatsino Indian Band, Coal Harbour Nanaimo North Island, Port Hardy Port Alberni *Gwa’Sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Family Services, Pt. Hardy *Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Port Alberni* Klemtu Health Clinic, Port Hardy *Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Tofino *Kwakiutl Indian Band, Port Hardy Oceanside, Qualicum Beach Comox Valley, Courtenay Campbell River Pages 9-12 INTERIOR REGION Princeton *First Nations Friendship Centre Nicola Valley, Merritt Kelowna *Nzen’man’ Child & Family, Lytton *KiLowNa Friendship Society, Kelowna Lillooet South Okanagan, Penticton; Oliver Kamloops *Lower Similkameen Indian Band, Keremeos Clearwater Boundary, Grand Forks South Cariboo, 100 Mile House West Kootenay, Castlegar Williams Lake Creston *Bella Coola East Kootenay, Cranbrook; Invermere Salmon Arm Golden *Splatstin, Enderby Revelstoke Vernon Pages 13-14 NORTH REGION Quesnel Golden Kitimat Robson*Splatsin, Valley Enderby Prince RupertRevelstoke Prince George Queen Charlotte Islands Vanderhoof Mackenzie *Tl’azt’en Nation, Tachie South Peace, Dawson Creek Burns Lake Fort St. -

AT a GLANCE 2021 Metro Vancouver Committees

AT A GLANCE 2021 Metro Vancouver Committees 19.1. Climate Action Electoral Area Carr, Adriane (C) – Vancouver McCutcheon, Jen (C) – Electoral Area A Dhaliwal, Sav (VC) – Burnaby Hocking, David (VC) – Bowen Island Arnason, Petrina – Langley Township Clark, Carolina – Belcarra Baird, Ken – Tsawwassen De Genova, Melissa – Vancouver Dupont, Laura – Port Coquitlam Long, Bob – Langley Township Hocking, David – Bowen Island Mandewo, Trish – Coquitlam Kruger, Dylan – Delta McLaughlin, Ron – Lions Bay McCutcheon, Jen – Electoral Area A Puchmayr, Chuck – New Westminster McIlroy, Jessica – North Vancouver City Wang, James – Burnaby McLaughlin, Ron – Lions Bay Patton, Allison – Surrey Royer, Zoe – Port Moody Finance and Intergovernment Steves, Harold – Richmond Buchanan, Linda (C) – North Vancouver City Yousef, Ahmed – Maple Ridge Dhaliwal, Sav (VC) – Burnaby Booth, Mary–Ann – West Vancouver Brodie, Malcolm – Richmond COVID–19 Response & Recovery Task Force Coté, Jonathan – New Westminster Dhaliwal, Sav (C) – Burnaby Froese, Jack – Langley Township Buchanan, Linda (VC) – North Vancouver City Hurley, Mike – Burnaby Baird, Ken – Tsawwassen First Nation McCallum, Doug – Surrey Booth, Mary–Ann – West Vancouver McCutcheon, Jen – Electoral Area A Brodie, Malcolm – Richmond McEwen, John – Anmore Clark, Carolina – Belcarra Stewart, Kennedy – Vancouver Coté, Jonathan – New Westminster Stewart, Richard – Coquitlam Dingwall, Bill – Pitt Meadows West, Brad – Port Coquitlam Froese, Jack – Langley Township Harvie, George – Delta Hocking, David – Bowen Island George -

Bowen Island

Conservation status of Bowen Island Bowen Island is one of 13 local trust areas and island The Islands Trust Conservancy does “nature check-ups” to municipalities that make up the Islands Trust Area. Located in measure the state of island ecosystems to see how well we are Howe Sound just a twenty-minute ferry ride from Horseshoe meeting the Islands Trust’s mandate to “preserve and protect”. Bay in West Vancouver, it includes Bowen and Hutt islands. Guided by a science-based Regional Conservation Plan, our Bowen is within the traditional territories of numerous First work is important because, like the species and habitats that Nations who have cared for these lands and waters since time support us, the quality of human life depends on ecosystem immemorial. health. We all have a part to play in protecting these fragile islands in the Salish Sea for future generations. Beautiful Bowen is home to some of the rarest ecosystems in British Columbia that are under threat from development, climate change and habitat degradation. Species at risk Parks & protected areas Blue dasher, (Pachydiplax longipennis) Special Concern (Federally), blue listed (Provincially) 21% PROTECTED sensitive to human activities Recorded sightings on Bowen Island Marbled Murrelet, (Brachyramphus marmoratus) Threatened (Federally), blue listed (Provincially) Critical habitat for marbled murrelet on provincial and private lands LandNatural Converted Areas Converted to Human for Human Use Use in in the Islands Islands Trust TrustArea Area Bowen Mayne etis Gabriola Galiano Hornby Saturna Denman Executive Gambier Lasqueti Salt Spring North Pender South Pender Once land is converted for human use, that land is less available for nature. -

Outstation Information Guides

ALEXANDRA’S HIGHLIGHTS ALEXANDRA ISLAND Great Summer Swimming INFORMATION GUIDE Safe Shelter Docking all year round Hiking Fishing On-Dock Barbecuing Get back to nature Great Scenery Toilet facilities on-shore ROYAL VANCOUVER YACHT CLUB The RVYC burgee must ALWAYS be flying on approach GPS Coordinates: and vessel must be under the direct control of a member. 49.4685947 / -123.3857335,17 The Member is responsible for the conduct of their guests (and any damage they may cause) There is no smoking anywhere above the dock by mem- bers or their guests. Penalties for non-compliance of any of these rules (in this brochure, or in the yearbook) can result in the loss of Offshore Station privileges for up to one year. ABOUT ALEXANDRA ISLAND MAPSTATION RULES INTERNET ACCESS The island has 1,200 feet of dock space, limited trails Alexandra Island is equipped with wireless internet (please keep pets leashed at all times and remove all service. BBX is the provider, and users can set up droppings), a gazebo style pavilion, covered on-dock pay-per-use accounts in addition to monthly or annual barbecue, horseshoe pit, 4 kayaks, and washrooms. subscriptions. Excellent swimming, windsurfing, and crabbing are a If broadband service is unavailable, please contact the few of the highlights of a stop-off here. A safe haven technician at 1.360.961.2251 when the Gulf is heaving. EMERGENCIES & FIRST AID No shore power. IN AN EMERGENCY, CONTACT 9-1-1 A NOTE OF CAUTION: A drying reef is located just off of the east shore DISTANCE FROM JERICHO IN THE AREA Alexandra Island is located 18 nm NNW from Jericho Home Port. -

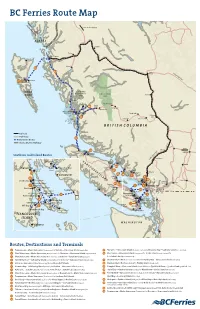

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

Capacity Chart Floor Plan

FLOOR PLAN CONFERENCE FLOOR BOARDROOM WADDINGTON ROOM STAGE PACIFIC BALLROOM HORNBY ROOM BANQUET OFFICE GRAND STAIRCASE PACIFIC FOYER STAIRS TWEEDS- MUIR VANCOUVER ISLAND ROOM ROOM BURRARD ROOM ELEVATORS LIONS ROOM BRITISH COLUMBIA FOYER BRITISH COLUMBIA BALLROOM SERVICE BRITISH BALLROOM KITCHEN COLUMBIA BALLROOM FREIGHT ELEVATOR CAPACITY CHART OVERALL DIMENSIONS SQUARE HEIGHT CAPACITIES HOLLOW FEET METRES FEET METRES FEET METRES ROUNDS THEATRE CLASSROOM BOARDROOM RECEPTION U-SHAPE SQUARE BC BALLROOM 100' x 114' 30.5 x 34.7 11,400 1,058 14' 4" 4.4 420 336 204 – 750 – – BRITISH BALLROOM 100' x 54' 4" 30.5 x 16.5 5,430 503 14' 4" 4.4 210 120 90 30 400 34 42 COLUMBIA BALLROOM 100' x 59' 5" 30.5 x 18.1 5,940 552 14' 4" 4.4 210 120 90 30 400 34 42 PACIFIC BALLROOM 128' x 54' 39 x 16.5 6,900 644 23' 6" 7.2 264 204 120 38 400 44 50 VANCOUVER ISLAND 80' x 31' 24.4 x 9.5 2,500 232 16' 4.9 102 72 44 26 150 24 28 WADDINGTON 59' x 34' 18 x 10.4 2,000 187 11' 6" 3.5 90 56 32 20 100 20 24 BOARDROOM 36' x 34' 11 x 10.4 1,224 114 18' 5.5 54 32 20 12 75 12 16 TWEEDSMUIR 38' x 22' 11.6 x 6.7 836 78 11' 3.4 30 16 12 12 35 10 12 LIONS 22' x 14' 6.7 x 4.3 310 29 11' 3.4 12 8 3 8 10 – – BURRARD 19' x 10' 5.8 x 3 200 17 11' 3.4 6 – – 6 – – – HORNBY 20' x 10' 6.1 x 3 200 18 11' 3.4 6 – – 4 – – – FLOOR PLAN THE ROOF DISCOVERY FLOOR PENDER ISLAND SERVICE KITCHEN BOWEN ISLAND LANGARA ISLAND EDGECOMB ISLAND ELEVATORS FOYER SALT- SPRING SERVICE PANTRY ISLAND A MORESBY SALT- COAT SERVICE SPRING ISLAND AREA CHECK ISLAND ELEVATORS B SATURNA FOYER SALT- SPRING DENMAN -

Vancouver Canada Public Transportation

Harbour N Lions Bay V B Eagle I P L E 2 A L A 5 A R C Scale 0 0 K G H P Legend Academy of E HandyDART Bus, SeaBus, SkyTrain Lost Property Customer Service Coast Express West Customer Information 604-488-8906 604-953-3333 o Vancouver TO HORSESHOE BAY E n Local Bus Routes Downtown Vancouver 123 123 123 i CHESTNUT g English Bay n l Stanley Park Music i AND LIONS BAY s t H & Vancouver Museum & Vancouver h L Anthropology Beach IONS B A A W BURRARD L Y AV BURRARD Park Museum of E B t A W Y 500 H 9.16.17. W 9 k 9 P Y a Lighthouse H.R.MacMillan G i 1 AVE E Vanier n Space Centre y r 3 AVE F N 1 44 Park O e s a B D o C E Park Link Transportation Major Road Network Limited Service Expo Line SkyTrain Exchange Transit Central Valley Greenway Central Valley Travel InfoCentre Travel Regular Route c Hospital Point of Interest Bike Locker Park & Ride Lot Peak Hour Route B-Line Route & Stop Bus/HOV Lane Bus Route Coast Express (WCE) West Millennium Line SkyTrain Shared Station SeaBus Route 4.7.84 A O E n Park 4 AVE 4 AVE l k C R N s H Observatory A E V E N O T 2 e S B University R L Caulfeild Columbia ta Of British Southam E 5 L e C C n CAULFEILD Gordon Memorial D 25 Park Morton L Gardens 9 T l a PINE 253.C12 . -

The Ground Slate Transition on the Northwest Coast: Establishing a Chronological Framework

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 10-10-2014 The Ground Slate Transition on the Northwest Coast: Establishing a Chronological Framework Joshua Daniel Dinwiddie Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dinwiddie, Joshua Daniel, "The Ground Slate Transition on the Northwest Coast: Establishing a Chronological Framework" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2076. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2075 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Ground Slate Transition on the Northwest Coast: Establishing a Chronological Framework by Joshua Daniel Dinwiddie A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Anthropology Thesis Committee: Kenneth M. Ames, Chair Shelby L. Anderson Virginia L. Butler Portland State University 2014 © 2014 Joshua Daniel Dinwiddie Abstract This thesis establishes the earliest appearance of ground slate points at 50 locations throughout the Northwest Coast of North America. Ground slate points are a tool common among maritime hunter-gatherers, but rare among hunter-gatherers who utilize terrestrial subsistence strategies; ground -

Aboriginal Relations Committee Agenda Package

GREATER VANCOUVER REGIONAL DISTRICT ABORIGINAL RELATIONS COMMITTEE REGULAR MEETING Thursday, October 6, 2016 1:00 p.m. 2nd Floor Boardroom, 4330 Kingsway, Burnaby, British Columbia R E V I S E D A G E N D A1 1. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA 1.1 October 6, 2016, Regular Meeting Agenda That the Aboriginal Relations Committee adopt the agenda for its regular meeting scheduled for October 6, 2016, as circulated. 2. ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES 2.1 February 4, 2016, Regular Meeting Minutes That the Aboriginal Relations Committee adopt the minutes of its regular meeting held February 4, 2016, as circulated. 3. DELEGATIONS 4. INVITED PRESENTATIONS Corrected 4.1 Allyson Rowe, Associate Regional Director General, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada Subject: Effective Partnerships with Municipalities Additions to Reserve/New Reserves Policy, Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act (formerly Bill S-8), and First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act (FNCIDA) 4.2 Anita Boscariol, Director General, Negotiations West, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada Subject: Developments in Treaty and Negotiations 1 Note: Recommendation is shown under each item, where applicable. October 7, 2016 ARC - 1 5. REPORTS FROM COMMITTEE OR STAFF 2017 Budget and Annual Work Plan – Aboriginal Relations Designated Speaker: Ralph G. Hildebrand, General Manager, Legal & Legislative Services/Corporate Solicitor That the Aboriginal Relations Committee endorse the 2017 Aboriginal Relations Work Plan and Budget as presented in the report “2017 Budget and Annual Work Plan -

BC Recording Studios

AMPLIFY BC Career Development Recording Businesses 2020/2021 CARIBOO REGION City Studio Name Contact Website Prince George Pulp City Records Connor Pritchard Prince George Vinyl Deck Studios William Kuklis www.williamkuklis.com www.facebook.com/Thriving-Road- Prince George Thriving Road Productions Michael Amos Productions KOOTNEY REGION City Studio Name Contact Website Grand Forks PMT Studio Sacha Petulli www.pmtstudio.com Kimberly Twisted Cable Studios Daniel MacNeil www.twistedcablestudios.com Nakusp Clear Concept Audio Avery Bremner www.clearconceptaudio.com Slocan Sonicturtle Music Adham Shaikh www.sonicturtle.com Winlaw Sincerity Sound Studio Barry Jones www.sinceritysound.com Ymir All Ears Music Productions Dave Ronald www.allearsmusicproductions.com Ymir Becoming Sound Shawn Stephenson www.becomingsound.ca NECHAKO REGION City Studio Name Contact Website www.smithersmusic.com/index.php/instruc Smithers Old Highway Studios Colin Maskell tors/colin-maskell THOMPSON OKANOGAN REGION City Studio Name Contact Website Coldstream Bailey Way Entertainment Jeff Johnson www.baileywayent.com Kamloops Perry's Recording Studio Douglas Perry www.perrysrecordingstudio.net Kamloops Shadybrook Studio James Bethell www.shadybrook.sudohuman.com Kelowna Arc House Studios Adam Wittke www.archousestudios.com Kelowna Frequency Wine and Sound Jodie Bruce www.frequencywinery.com/studio Kelowna IrieCan Entertainment Lias Hills-Lalonde www.IrieCan.com Kelowna Sounds Suspicious Andrew Judah Peachland Stu Goldberg Studios Stu Goldberg www.stugoldberg.com Vernon