IBP Journal (2020, Vol. 45, Issue No. 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Committee Daily Bulletin

CCoommmmiitttteeee DDaaiillyy BBuulllleettiinn 17th Congress A publication of the Committee Affairs Department Vol. III No. 50 Third Regular Session November 19, 2018 BICAMERAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE MEETING MEASURES COMMITTEE PRINCIPAL SUBJECT MATTER ACTION TAKEN/ DISCUSSION NO. AUTHOR Bicameral HB 5784 & Rep. Tan (A.) Instituting universal health care for all The Bicameral Conference Committee, co- Conference SB 1896 and Sen. Recto Filipinos, prescribing reforms in the health presided by Rep. Angelina "Helen" Tan, M.D. Committee care system and appropriating funds (4th District, Quezon), Chair of the House therefor Committee on Health, and Sen. Joseph Victor Ejercito, Chair of the Senate Committee on Health and Demography, will deliberate further on the disagreeing provisions of HB 5784 and SB 1896. The Department of Health (DOH) and the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) were requested to submit their respective proposals on the premium rate, income ceiling and timeframe to be adopted in relation to the provision increasing the members’ monthly PhilHealth premium. Other conferees who were present during the bicameral conference committee meeting were the following: On the part of the House, Deputy Speaker Evelina Escudero (1st District, Sorsogon), Reps. Jose Enrique "Joet" Garcia III (2nd District, Bataan), Arlene Arcillas (1st District, Laguna), Estrellita Suansing (1st District, Nueva Ecija), Cheryl Deloso-Montalla (2nd District, Zambales), and Ron Salo (Party- List, KABAYAN); on the part of the Senate, Senators, Ralph Recto, Risa Hontiveros, and Joel Villanueva. Also present were former Reps. Karlo Alexei Nograles and Harry Roque Jr., DOH Secretary Francisco Duque III, and Dr. Roy Ferrer, acting President and CEO of PhilHealth. Bicameral HB 5236 & Rep. -

Diplomacy” with China Made the Philippines a COVID‐19 Hotspot in Southeast Asia by Sheena A

Number 541 | December 16, 2020 EastWestCenter.org/APB “Diplomacy” with China Made the Philippines a COVID‐19 Hotspot in Southeast Asia By Sheena A. Valenzuela When the news of a mysterious illness in mainland China came to light in late December 2019, some states treated it seriously and acted with urgency to migate potenal transmission of the disease and its harmful impacts on economic and social security. For instance, the Vietnamese government recognized the coronavirus outbreak as a threat early on. In a statement on January 27, 2020, Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc likened the fight against the coronavirus to “fighng against enemies” and stressed that “the Government accepts economic losses to protect the lives and Sheena A. Valenzuela, health of people”. Three days aer the pronouncement, Vietnam closed its shared borders with China Research Associate at and banned flights to and from its neighbor. Vietnam adopted these measures despite the fact that its the Ateneo School of economy is closely linked to China, its largest trading partner. Government in the On the other hand, the Philippines downplayed the threat of the virus and waited unl transmission Philippines, explains had accelerated within its borders before implemenng countermeasures. When the first COVID‐19 that: “The Philippines case was reported in the country on January 30, the public became increasingly worried and some downplayed the threat groups called for a ban on flights from China. However, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte stated of the virus and waited that he was not keen on stopping tourist traffic from China, as “it would not be fair.” Department of unl transmission had Health (DOH) Secretary Francisco Duque III supported Duterte’s posion, saying that a ban “would be accelerated within its tricky” and that it would spark “polical and diplomac repercussions” because the virus was not borders before confined to China alone. -

05 MARCH 2021, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC March 05, 2021 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 1 Opinion Page Feature Article

05 MARCH 2021, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC March 05, 2021 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 1 Opinion Page Feature Article DENR, Police partner for greening program in Tarlac By Gabriela Liana BarelaPublished on March 4, 2021 TARLAC CITY, March 4 (PIA) -- Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and Tarlac Police Provincial Office partnered in forest protection and greening program. Under the agreement, DENR will work with the 10 Municipal Police Stations (MPS) in the 1stcongressional district and the 2nd Provincial Mobile Force Company in protecting and developing the established forest plantations under the National Greening Program (NGP). Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Officer Celia Esteban said the police committed to protect and develop some 20 hectares NGP plantations found in Sitio Canding and Sitio Libag in Barangay Maasin of San Clemente town. “After three years, the established NGP plantations have no more funds for protection and maintenance and this is where the police will enter to adopt these areas which were established by our partner people’s organizations," Esteban explained. MPS shall also act as the overall project manager and shall take charge in the mobilization of personnel prioritizing in hiring the people's organizations within the area. Department of Environment and Natural Resources and Tarlac Police Provincial Office partnered in forest protection and greening program. (DENR) Moreover, they will be responsible in the funding of survey, mapping and planning, produce seedlings for replanting, maintenance and protection of the adopted plantation. DENR, on the other hand, shall provide them technical assistance in relation to the project. Camiling MPS Chief PLtCol. -

Shut-Down of Duterte-Critical News Group Seen As Attack on Press

STEALING FREE NEWSPAPER IS STILL A CRIME ! AB 2612, PLESCIA CRIME Proposed legislature could abolish Senate WEEKLY ISSUE 70 CITIES IN 11 STATES ONLINE Vol. IX Issue 458 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 January 18 - 24, 2018 Shut-down of Duterte-critical news group PH NEWS | A2 seen as attack on press freedom By Daniel Llanto | FilAm Star Correspondent PH media has been fair - Pew Research For supposedly inviting foreign of Duterte as well as the leading ownership, the Securities and Ex- broadsheet Inquirer for various stated change Commission (SEC) revoked reasons. the certificate of incorporation of news For the closure of Rappler, op- website Rappler, shutting down the position senators and media organiza- popular news group known for critical tions cried out pure harassment and reporting of the Duterte administra- undisguised attack on press freedom. tion. “I strongly condemn the SEC’s It may just be coincidence that revocation of the registration of Rap- Rappler is headed by Managing pler,” Sen. Antonio Trillanes IV said. Director Maria Rissa who previously “It would also send a chilling message PH NEWS | A3 headed ABS-CBN News and Public to other media entities to force them Affairs as chief and that President to toe the Administration’s propa- Durant leads Warriors Duterte earlier gave Rappler a piece ganda lines.” victory against Cavs of his mind for its alleged foreign Sen. Risa Hontiveros found it “a (L-R) Rappler Managing Director Maria Ressa and eBay founder Pierre Omidyar funding. ABS-CBN is in the crosshairs (Photos: www.techinasia.com / www. -

TIMELINE: the ABS-CBN Franchise Renewal Saga

TIMELINE: The ABS-CBN franchise renewal saga Published 4 days ago on July 10, 2020 05:40 PM By TDT Embattled broadcast giant ABS-CBN Corporation is now facing its biggest challenge yet as the House Committee on Legislative Franchises has rejected the application for a new broadcast franchise. The committee voted 70-11 in favor of junking ABS-CBN’s application for a franchise which dashed the hopes of the network to return to air. Here are the key events in the broadcast giant’s saga for a franchise renewal: 30 March, 1995 Republic Act 7966 or otherwise known as an act granting the ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation a franchise to construct, install, operate and maintain television and radio broadcasting stations in the Philippines granted the network its franchise until 4 May 2020. 11 September, 2014 House Bill 4997 was filed by Isabela Rep. Giorgidi Aggabao and there were some lapses at the committee level. 11 June, 2016 The network giant issued a statement in reaction to a newspaper report, saying that the company had applied for a new franchise in September 2014, but ABS-CBN said it withdrew the application “due to time constraints.” 5 May, 2016 A 30-second political ad showing children raising questions about then Presidential candidate Rodrigo Duterte’s foul language was aired on ABS-CBN and it explained it was “duty-bound to air a legitimate ad” based on election rules. 6 May, 2016 Then Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte’s running mate Alan Peter Cayetano files a temporary restraining order in a Taguig court against the anti-Duterte political advertisement. -

A Transformed Judiciary*

Chapter 1 A Transformed Judiciary* It is great to be home once again in this super University! My first speaking appearance at the Far Eastern University (FEU) Auditorium was some 50 years ago -- to be exact, 48 years ago in 1957 -- when as a young sophomore law student, I delivered my inaugural address as president of the FEU Central Student Organization. Thank you, FEU, for that invigorating memory, that exhilarating experience of heading the student body of the then largest educational institution in our country. Thank you also to two super ladies -- Dr. Lourdes Reyes-Montinola, chairperson of the FEU Board of Trustees; and Dr. Lydia B. Echauz, FEU president – who, along with super law Dean Andres D. Bautista, the perennial leader of the Philippine Association of Law Deans, are responsible for FEU’s generous co-sponsorship of this tenth lecture in the Chief Justice Hilario G. Davide Jr. Distinguished Lecture Series. As some of you may know, this intellectual pursuit is one of several projects being held nationwide all year round to commemorate the many outstanding achievements of the Supreme Court during the seven-year term of our beloved Chief.[1] Ladies and gentlemen, Hilario G. Davide Jr. will be remembered in history as one of the greatest Chief Justices not only in our country, but also in the Asia-Pacific region. I am certain that whenever a history of the judiciary in our part of the world is written, he will always merit a sparkling chapter. Back in 1999 when I wrote Leadership by Example, just after his appointment as the “Centennial” or even “Millennial” Chief Justice, I already had an intimation of his impending renown. -

Mega Swabbing Center in Taguig City Opens to Boost COVID19 Testing Capacity

Date Released: 06 May 2020 Releasing Officer: DIR. ARSENIO R. ANDOLONG Chief, Public Affairs Service Mega Swabbing Center in Taguig City opens to boost COVID19 testing capacity Defense Secretary Delfin N. Lorenzana together with Health Secretary Francisco Duque III, Interior and Local Government Secretary Eduardo M. Año, National Action Plan Against COVID19 Chief Implementer Secretary Carlito G. Galvez, Jr., Deputy Chief Implementer Secretary Vince Dizon and Taguig City Mayor Lino Cayetano inspected and witnessed the opening of Mega Swabbing Center in Taguig City on 6 May 2020. ENDERUN COLLEGES, Taguig City – As part of the government’s continuous efforts to mitigate the spread and the effects on public health of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19), the second Mega Swabbing Center opened in Taguig City on 6 May 2020. The swabbing center can conduct 1,000 to 1,500 swabs daily, boosting the country’s health system capacities to detect, isolate and treat COVID19 patients. DND Press Release | Page 1 of 2 Secretary of National Defense Delfin N. Lorenzana, Health Secretary Francisco Duque III, Interior and Local Government Secretary Eduardo M. Año, National Action Plan Against COVID19 Chief Implementer Secretary Carlito G. Galvez, Jr., Deputy Chief Implementer Secretary Vince Dizon and Taguig City Mayor Lino Cayetano inspected and witnessed the opening of the facility. Health workers from the Department of Health will conduct the swabbing, while personnel from the Armed Forces of the Philippines will undertake the encoding part in the operations, according to Secretary Lorenzana. “We will supply personnel as bar coders and encoders from the Armed Forces, who will be trained to assist the swabbers in the Mega Swabbing Centers,” the Defense Chief said. -

IN the NEWS Strategic Communication and Initiative Service

DATE: ____JULY _1________3, 2020 DAY: _____MONDAY________ DENR IN THE NEWS Strategic Communication and Initiative Service STRATEGIC BANNER COMMUNICATION UPPER PAGE 1 EDITORIAL CARTOON STORY STORY INITIATIVES PAGE LOWER SERVICE July 13, 2020 PAGE 1/ DATE TITLE : DENR promotes plant-based diet to fight climate change 1/2 DENR promotes plant-based diet to fight climate change July 12, 2020, 2:53 pm MANILA – The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) on Saturday urged Filipinos to help fight climate change by switching to plant-based diet, which has been shown to reduce the ecological footprint of human food consumption. In a press release, the DENR, through its Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), has launched a month-long public information drive to encourage everyone to shift away from animal-based products towards consumption of more fruits and vegetables. The “Plant-Based Solutions for Climate Change” campaign, which coincides with the celebration of July as nutrition month, urges Filipinos to include more vegetables and fruits into their diet following the recommendation of the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) on proportion by three main food groups -- go, grow and glow foods. EMB Director William Cuñado said shifting to plant-based diet is one way to greatly reduce the environmental impact of one’s food consumption. “Switching to a plant-based diet not only benefits one’s health, it can also help protect the environment due to the smaller environmental footprints plant-based diets tend to have,” Cuñado said. According to a 2013 study by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, meat and dairy -- particularly from cows -- account for around 14.5 percent of the global greenhouse gases each year. -

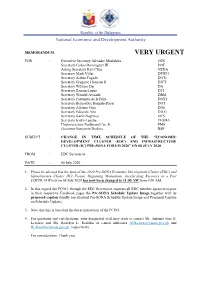

Change in Schedule of Pre-SONA Forum 2020

Republic of the Philippines National Economic and Development Authority MEMORANDUM VERY URGENT FOR : Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea OES Secretary Carlos Dominguez III DOF Acting Secretary Karl Chua NEDA Secretary Mark Villar DPWH Secretary Arthur Tugade DOTr Secretary Gregorio Honasan II DICT Secretary William Dar DA Secretary Ramon Lopez DTI Secretary Wendel Avisado DBM Secretary Fortunato de la Peña DOST Secretary Bernadette Romulo-Puyat DOT Secretary Alfonso Cusi DOE Secretary Eduardo Año DILG Secretary Karlo Nograles OCS Secretary Isidro Lapeña TESDA Undersecretary Ferdinand Cui, Jr. PMS Governor Benjamin Diokno BSP SUBJECT : CHANGE IN TIME SCHEDULE OF THE “ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CLUSTER (EDC) AND INFRASTRUCTURE CLUSTER (IC) PRE-SONA FORUM 2020” ON 08 JULY 2020 FROM : EDC Secretariat DATE : 06 July 2020 1. Please be advised that the time of the 2020 Pre-SONA Economic Development Cluster (EDC) and Infrastructure Cluster (IC) Forum: Regaining Momentum, Accelerating Recovery in a Post COVID-19 World on 08 July 2020 has now been changed to 11:00 AM from 9:00 AM. 2. In this regard, the PCOO, through the EDC Secretariat, requests all EDC member agencies to post in their respective Facebook pages the Pre-SONA Schedule Update Image together with its proposed caption (kindly see attached Pre-SONA Schedule Update Image and Proposed Caption on Schedule Update). 3. Note that this is based on the latest instruction of the PCOO. 4. For questions and clarifications, your designated staff may wish to contact Mr. Antonio Jose G. Leuterio and Ms. Rodelyn L. Rodillas at e-mail addresses [email protected] and [email protected], respectively. -

Evaluation of the Sixth UNFPA Country Programme to the Philippines 2005-2010

Evaluation of the Sixth UNFPA Country Programme to the Philippines 2005-2010 Prepared for: UNFPA Country Office, Manila, the Philippines Prepared by: Dr Godfrey JA Walker M.D. - Team Leader Dr. Magdalena C. Cabaraban, Ph.D. - Mindanao/ARMM Consultant Dr. Ernesto M Pernia, Ph.D. - PDS Consultant Dr. Pilar Ramos-Jimenez, Ph.D. - Gender and RH Consultant November 2010 Evaluation of the UNFPA Sixth Country Programme, Philippines 2005-2010 Table of Contents Page Map of the Philippines iv Acronyms v Executive Summary vii Background and Situation Analysis vii Evaluation Purpose, Audience and Methodology vii Main Conclusions vii Sustainability x Relevance x Impact – Effectiveness xi Factors Facilitating CP Success xi Efficiency xii Main Recommendations for the 2012-2016 Country Programme xii 1. UNFPA and Evaluation 1 2 Scope and Objectives of the Evaluation of the Sixth UNFPA Philippines Country Programme 1 3 Methods Used in the Evaluation 2 4 Country Background and Context 3 5 The Sixth UNFPA Philippines Country Programme 5 6 Review of Implementation of the PDS Component of the Country Programme 9 7 Review of Implementation of the RH Component of the Country Programme 21 7.1 Maternal Health 23 7.2 Family Planning 40 7.3 Adolescent Reproductive Health 47 7.4 HIV and AIDS 55 7.5 UNFPA’s Humanitarian Response Strategy for RH and SGBV 62 8 Review of Implementation of the Gender & Culture Component of the Country Programme 64 9 Review of Implementation of the Sixth Country Programme in Mindanao 75 10 UNFPA and Implementation of UNDAF, Joint UN Programmes and South to South Co-operation 89 11 Monitoring Implementation of the CP and Assessment of Overall Achievement ii Evaluation of the UNFPA Sixth Country Programme, Philippines 2005-2010 of the Targets Set in the CPD and CPAP 2005-2009 93 12 Management of the Country Programme: Complementarity, Coordination and Integration of RH, PDS, Gender and Culture. -

No Letup in Fight Vs. Illegal Wildlife Trade Posted April 07, 2020 at 05:40 Pm by Rio N

STRATEGIC BANNER COMMUNICATION UPPER PAGE 1 EDITORIAL CARTOON STORY STORY INITIATIVES PAGE LOWER SERVICE April 8, 2020 PAGE 1/ DATE TITLE : DENR: No letup in fight vs. illegal wildlife trade posted April 07, 2020 at 05:40 pm by Rio N. Araja Amid the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic, Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu on Tuesday vowed to pursue the government’s fight against illegal wildlife trade and uphold the country's ecological integrity. “We will not be complacent even in today’s worst global humanitarian crisis. We assure the public that the Department of Environment and Natural Resources would not cease in going after illegal wildlife trade criminals, especially those who have seized the opportunity to take advantage of the crisis through wildlife trafficking,” Cimatu said. He lauded their wildlife enforcers for their continued coordination with all of their partner agencies, particularly with the Bureau of Customs and the National Bureau of Investigation, to fight illegal wildlife trade. “Just like the other front liners in health, food security, social service, military and economic government institutions, our indefatigable wildlife enforcers have committed to continue with their public service and duty to protect our country’s natural resources. For the same sacrifices they make, we ought to give them their much-deserved salute,” Cimatu said. Source: https://manilastandard.net/news/national/321260/denr-no-letup-in-fight-vs-illegal-wildlife- trade.html?fbclid=IwAR2NnPYpyxxyIFVHPvYI2JtISDyuR2ERy9o1r9P_NlGQJkTpryHcYOTGEag -

DEPARTMENT of FINANCE Roxas Boulevard Corner Pablo Ocampo, Sr

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE Roxas Boulevard Corner Pablo Ocampo, Sr. Street Manila 1004 REGAINING MOMENTUM, ACCELERATING RECOVERY IN A POST-COVID-19 WORLD Carlos G. Dominguez Secretary of Finance Pre-SONA Briefing July 8, 2020 Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea; Infrastructure Cluster Chairman and Secretary of Public Works and Highways Mark Villar; Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Governor Benjamin Diokno; Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles; members of the Economic Development and Infrastructure Clusters; fellow workers in government; members of the diplomatic corps; business and financial communities; academe, civil society, youth organizations, development partners, friends in media: Good morning. We live in difficult and uncertain times. In a country whose median age is below twenty-five, the COVID-19 health emergency is perhaps the toughest economic crisis most of our people will live through. This pandemic is a “black swan” event that no one fully anticipated and was truly prepared to deal with. But we did not fold and run in the face of an unprecedented crisis. We quickly took stock of the situation and responded with everything we had. President Duterte’s early and decisive measures to combat the contagion saved thousands of lives. According to the Epidemiological Models by the FASSSTER Project in April and the University of the Philippines COVID-19 Pandemic Response Team as of June 27, government interventions such as the lockdown have prevented as much as 1.3 to 3.5 million infections. Imposing the enhanced community quarantine not only slowed the virus’ spread, when it could have grown exponentially faster. The lockdown gave us time to expand our testing capacity by multiples.