Mcteague's Gilded Prison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

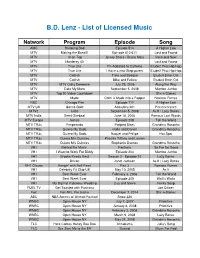

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

Spring 2015: View Our

This zine is a product of Feminist Studies 150H Spring 2015 Too young to know Kasey Reinbold my baby brother smiles and coos at the woman making faces laughing hovering above him. “what a ladies man!” they all proclaim. my baby brother turns fifteen and tells us he does not feel sexual attraction: ASEXUAL. my mother’s tongue rejects the word. “you’re too young to know for sure.” the parade in the summer boasts rainbows and glitter and corporate sponsorships. it sings, “we were born this way!” and leaves a sour taste in my mouth. i think the hateful folks may be onto something. maybe our passions and our lusts are a choice. but that choice sure as hell isn’t ours. This is a love letter Jill Pember wrote to her boyfriend. She plans to give it to him before she leaves Santa Barbara for the summer Monika Terry Mass Media: Where No Means Try Harder By Josephine BergillGentile I was recently watching TV and came across a scene from the movie The Devil Wears Prada. The scene is portrayed as highly romantic where the main character, a female, is walking through the streets of Paris at night accompanied by a man. The man kisses her, something she responds to with hesitation stating that she and her longterm boyfriend had just broken up. He proceeds to kiss her as she lists reasons such as, “I’ve had too much to drink and my judgment is impaired,” and ”I barely know you and I’m in a strange city.” Eventually she claims to be out of excuses and she winds up in his hotel room. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

The Maroon Tiger MOREHOUSE COLLEGE ATLANTA, GEORGIA

The Organ ofStudent Expression Serving Morehouse College Since 1898 The Maroon Tiger MOREHOUSE COLLEGE ATLANTA, GEORGIA m THIS EDITION New Student Orientation Recap emony. Students were left with Morehouse College Welcomes the Class of2006 the charge to take on all that had been placed before them. Nick Sneed tions depicting Morehouse Campus News of and contributors to society. Although tears were shed by Contributing Writer College history, including As the week went on, parents and students alike, Campus Safety noted alumni, past presidents "We don't need no students and parents received there was not a need for them and institutional goals. The hours to rock information about the various in essence. the house!" During T h "The Expecta Morehouse tions of a College Morehouse 4rts & Entertainment of 2006 Man" session, alumnus Dr. Trick Daddy and Trina Re- rived on cam ’ Calvin Mackey views pus Tuesday, August 20, told the story of some 800 stu how he and his dents strong, mother parted as the N ways his first f year at Page 7 Student Ori- entation Morehouse. As Features (NSO) staff she departed he shed a tear. She lead about Soul Vegetarian we 1 c o m e d saw him in her —more than a restaurant them to "The House." rearview mirror Page 8 The and turned the weeklong fes- car around. She went back to tivities offi where he was cially began standing and that evening asked why he in front of was crying. He Pius Kilgore Hall. told her that he The entire Senate Hopeful Ron Kirk was sad to see class formed a her go. -

Ludacris, What Means the World to You (Remix)

Ludacris, What Means The World To You (Remix) [Ludacris] Track Mas-ter-rrrah! What means the world to me? Snappin bras, menage-a-trois What means the world to me? Smokin hash, slappin ass What means the world to me? Breakin laws, racin cars What means the world to me? Makin bail, A-T-L [Cam'Ron] Uhh, uhh What mean the world to me? When I bang hoes, sky blue Range Rov's Stop comin to my crib with your period Serious bitch, and you act like I ain't know I like my dishes deep, I like when I twist a freak I like when her man find out when the court came mouse Laugh when he went for me; I tell him Women are trife - yeah I been in your wife but do me a favor, dog Don't call here again in your life, I'm killer Atlanta I bubbled, in Memphis I hustled In Kansas I juggle, New York, all my muscle we tussle Listen you would too, if you knew what this game would do to you Been in this shit, two years Boo Look at all the bullshit I been through So called beef with you know who (who?) But I got max gats Nine nine's times nine, blow, blow, OW! (owww) [Ludacris] Let me tell 'em what'll mean the world Ludacris and a couple a girls You find a brotha runnin up in the girls I get 'em drunk, chugga-luggin the girls Ding-a-ling face huggin the girls I get late - think I'm up with the girls? Skeet, skeet, gone; it's all about that party Bacardi - motions, rub lotion, all over your body What means the world to me? A little head preferably, so I express this verbally And I don't care, I just want somebody to braid my hair Cause I keeps it nappy, I'm happy, and -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

THE BOARD of MASSAGE THERAPY Professional & Vocational Licensing Division Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs State of Hawaii

THE BOARD OF MASSAGE THERAPY Professional & Vocational Licensing Division Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs State of Hawaii MINUTES OF MEETING Date: Wednesday, January 31, 2018 Time: 9:00 a.m. Place: King Kalakaua Conference Room King Kalakaua Building 335 Merchant Street, First Floor Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Present: George Davis, Jr., Massage Therapist, Chair Paula Behnken, Public Member, Vice Chair Jodie Hagerman, Public Member Samantha Meehan-Vandike, Massage Therapist Carol Kramer, Executive Officer (“EO”) Shari Wong, Deputy Attorney General (“DAG”) Jennifer Fong, Secretary Excused: Stephanie Bath, Massage Therapist Guests: Tanya Raymond, Hellerwork Association Lei Fukumura, Professional & Vocational Licensing Division Special DAG Taylor Engcabo, Remington Rebekah Morris, Remington Don McCoy, Remington Kawika Palimo'o, Remington Megan Young, Hawaii School of Professional Massage Agenda: The agenda for this meeting was filed with the Office of the Lieutenant Governor, as required by section 92-7(b), Hawaii Revised Statutes ("HRS"). 1. Call to Order: There being a quorum present, Chair Davis called the meeting to order at 9:01 a.m. 2. Additional Distribution to Agenda: None. Board of Massage Therapy Minutes of the January 31, 2018 Meeting Page 2 3. Introduction of Chair Davis introduced Ms. Hagerman as the newest member of the Board, noting New Board that with her appointment the Board is now full. Member, Jodie Hagerman: Ms. Hagerman gave a brief self-introduction, noting that it was Chair Davis who informed her of the opening on the Board and encouraged her to submit an application. EO Kramer stated that Governor Ige appointed Jodie Hagerman as a public member on an interim basis, effective January 12, 2018. -

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021 EMPLOYER NAME and ADDRESS REGISTRATION EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYEE NAME NUMBER START DATE TERMINATION DATE Gold Crest Retirement Center (Nursing Support) Name of Contact Person: ________________________ Phone #: ________________________ 200 Levi Lane Email address: ________________________ Adams NE 68301 Bailey, Courtney Ann 147577 5/27/2021 Barnard-Dorn, Stacey Danelle 8268 12/28/2016 Beebe, Camryn 144138 7/31/2020 Bloomer, Candace Rae 120283 10/23/2020 Carel, Case 144955 6/3/2020 Cramer, Melanie G 4069 6/4/1991 Cruz, Erika Isidra 131489 12/17/2019 Dorn, Amber 149792 7/4/2021 Ehmen, Michele R 55862 6/26/2002 Geiger, Teresa Nanette 58346 1/27/2020 Gonzalez, Maria M 51192 8/18/2011 Harris, Jeanette A 8199 12/9/1992 Hixson, Deborah Ruth 5152 9/21/2021 Jantzen, Janie M 1944 2/23/1990 Knipe, Michael William 127395 5/27/2021 Krauter, Cortney Jean 119526 1/27/2020 Little, Colette R 1010 5/7/1984 Maguire, Erin Renee 45579 7/5/2012 McCubbin, Annah K 101369 10/17/2013 McCubbin, Annah K 3087 10/17/2013 McDonald, Haleigh Dawnn 142565 9/16/2020 Neemann, Hayley Marie 146244 1/17/2021 Otto, Kailey 144211 8/27/2020 Otto, Kathryn T 1941 11/27/1984 Parrott, Chelsie Lea 147496 9/10/2021 Pressler, Lindsey Marie 138089 9/9/2020 Ray, Jessica 103387 1/26/2021 Rodriquez, Jordan Marie 131492 1/17/2020 Ruyle, Grace Taylor 144046 7/27/2020 Shera, Hannah 144421 8/13/2021 Shirley, Stacy Marie 51890 5/30/2012 Smith, Belinda Sue 44886 5/27/2021 Valles, Ruby 146245 6/9/2021 Waters, Susan Kathy Alice 91274 8/15/2019 -

Rap Vocality and the Construction of Identity

RAP VOCALITY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY by Alyssa S. Woods A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Theory) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Nadine M. Hubbs, Chair Professor Marion A. Guck Professor Andrew W. Mead Assistant Professor Lori Brooks Assistant Professor Charles H. Garrett © Alyssa S. Woods __________________________________________ 2009 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. I would like to thank my advisor, Nadine Hubbs, for guiding me through this process. Her support and mentorship has been invaluable. I would also like to thank my committee members; Charles Garrett, Lori Brooks, and particularly Marion Guck and Andrew Mead for supporting me throughout my entire doctoral degree. I would like to thank my colleagues at the University of Michigan for their friendship and encouragement, particularly Rene Daley, Daniel Stevens, Phil Duker, and Steve Reale. I would like to thank Lori Burns, Murray Dineen, Roxanne Prevost, and John Armstrong for their continued support throughout the years. I owe my sincerest gratitude to my friends who assisted with editorial comments: Karen Huang and Rajiv Bhola. I would also like to thank Lisa Miller for her assistance with musical examples. Thank you to my friends and family in Ottawa who have been a stronghold for me, both during my time in Michigan, as well as upon my return to Ottawa. And finally, I would like to thank my husband Rob for his patience, advice, and encouragement. I would not have completed this without you. -

Induction of the Forty Under 40 2017 Class Saturday, April 8, 2017 • 7:00 P.M

WSSU Induction of the Forty Under 40 2017 Class Saturday, April 8, 2017 • 7:00 p.m. SPECIAL TO OUR FORTY UNDERThank 40 COMMITTEE Y o u MEMBERS Siobahn Day ’05, YAC Co-Chair Mo Wright ’01, YAC Co-Chair Andrew Jones ’08, Fundraising Co-Chair Anthony Jones ’07, Fundraising Co-Chair Kamille Jones ’01, Young Alumni Engagement Co-Chair Tiffany Richmond ’06, Events Chair Denise A. Smith ’01, STAT Chair Jamie Tindal ’10, Young Alumni Engagement Co-Chair Committee Members Cherika Boyd ’07 Theodis Chunn ’15 Shondale Clark ’13 Arrica DuBose ’02 Latricia Giles ’15 Trina Holiness ’01 Teela Hopkins ’07 Marques Johnson ’04 Candace LaRochelle ’02 Kamilah Merritt ’01 Jonathan Murray ’04 Kidada Moore ’14 Deidra Phyall ’05 Haven Powell ’08 Ladia Rutledge ’07 Courtney Smith ’02 Shenequa “Nikki” Thomas ’05 & ’10 NeSheila Washington ’01 Denise Watson ’06 Trace Young ’08 WSSU FORTY UNDER 40 GALA PROGRAM Induction of the Forty Under 40 Class WELCOME Tiffany Richmond ’06 MISTRESS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES Siobahn Day ’05 & Mo Wright ’01 GREETINGS Elwood L. Robinson, Ph.D. Chancellor, Winston-Salem State University Victor Bruinton ’82 President, National Alumni Association Mona Zahir ’17 WSSU SGA President INVOCATION Dr. Timothy L. Freeman ’01 MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENT Groove Food Band DINNER DINNER SPEAKER Derwin L. Montgomery ’10 Councilmember, City of Winston-Salem PRESENTATION OF THE 2017 FORTY UNDER 40 HONOREES Siobahn Day & Mo Wright SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS Jonathan Murray ’04, Marques Johnson ’04 Anthony Jones ’07 CLOSING REMARKS Siobhan Day & Mo Wright ALMA MATER Saturday, April 8, 2017 • 7:00 pm • Benton Convention Center - Piedmont Room IV 1 Greetings: Welcome to the 2017 “Forty Under 40” Awards Gala, where we celebrate 40 communities. -

"Uncle Luke" Campbell Is the "I Am Hip Hop" Award Recipient

September 28, 2017 305's Very Own and Hip Hop Pioneer Luther "Uncle Luke" Campbell is the "I Am Hip Hop" Award Recipient Highly Anticipated Billboard's Hot 100 #1 Female Rapper Cardi B Confirmed to Perform ------ Also Hitting the Stage with Unforgettable Performances: DJ Khaled, Migos, Yo Gotti, Rick Ross, Trina, Trick Daddy, Flo Rida, T-Pain, Playboi Carti, Plies and Many More ------ The BET "HIP HOP AWARDS" 2017 is Hosted by DJ Khaled and Will Be Taping in Miami, FL on Friday, October 6, 2017 at The Fillmore Miami Beach at Jackie Gleason Theater and Premiering on Tuesday, October 10, 2017 at 8PM ET/PT ------ #HIPHOPAWARDS NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- The BET "HIP HOP AWARDS" has remained the most prominent hip hop showcase on television for ten years with its powerful performances, iconic hip hop honorees and much-anticipated cyphers. Multi- platinum artist, mega-producer and ‘Anthem King' DJ Khaled will take the reins as host of the BET "HIP HOP AWARDS" 2017. The "I Am Hip Hop" Award returns to honor hip hop pioneer and legend Luther "Uncle Luke" Campbell. Luther "Uncle Luke" Campbell is a businessman, community activist, author, television personality, radio host, artist and most importantly the first Southern rapper to appear on Billboard's Pop charts. In addition, he was the first Southern rapper to start an independent rap record label, Luke Records. Known as the "Godfather of Southern Hip Hop," Luther Campbell was the first in the music industry to provide "parental advisory" stickers on product responsibly ensuring his music was only bought by those of a certain age.