Use of Force During Arrest in Geraldine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No 56, 12 July 1928, 2215

Jumb. 56. 2215 SUPPLEMENT •ro THR NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE OF THURSDAY, JlJLY 12, 1928. .. ' '· ~.ubli~1tb; by '.aut~orit» . :.Ji: WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 12, 1928. Tenders for lnl,and Mail-service Contracts-South Isla.nd, 11. Blumine Island, Onauku, Otanerau, Greensill, Whare 1929-31. hunga, and Kilmarnock, weekly. (Contractor to take 1 delivery of mails off Blumine Island from mail launch General Post Office, proceeding from Picton to Resolution Bay.) Wellington, 9th July, 1928. 12. Canvastown and Deep Creek, twice weekly. EALED tenders will be received at the several Chief 13. Havelock, .Brightlands, Elaine Bay, Waitata Bay, Bulwer, S Post-offices in the South Island until noon on Thursday, Port L1gar, Forsyth Island, Wakatahuri, Te Puru, the 23rd August, 1928, for the conveyance of mails between Okoba, Anakoha, Titirangi, Pohuenui, Waimaru, Clova the undermentioned places, for a period of THREE YEARS, Bay, Manaroa, Hopai, Eli Bay, Crail Bay, Taranui, from the 1st January, 1929 :- Homewood, and Havelock, twice weekly. (Alternative to Nos. 14 and 25.) POSTAL DlsTRIOT OF BLENHEIM. 14. Havelock, Brightlands, Elaine Bay, Te Towaka, Waitata 1. Blenheim Chief Post-office, delivery of parcels and post Bay, Bulwer, Port Ligar, Forsyth Island, Wakatahuri, men's bags, as required. Te Puru, Okoha, Anakoha, Titirangi, Pohuenui 2. Blenheim, Jordan, and Molesworth, weekly. B~trix Bay,. Waimaru, Clova Bay, Manaroa, Hopai: 3. Blenheim and Netherwood (private-bag delivery), twice Eh Bay, Crail Bay, Taranui, Homewood, and Have weekly. lock, twice weekly. (Alternative to Nos. 13 and 25.) 4. Blenheim and Omaka, along Maxwell Road, over Taylor 15. Havelock, Broughton Bay, Portage, Kenepuru Head, River-bed, New Renwick Road to Fairhall Valley, Waitaria Bay, and St. -

Off-Road Walking and Biking Strategy 2012 to 2032

Off-Road Walking and Biking Strategy 2012 to 2032 Prepared by Bill Steans, Parks and Recreation Manager and Gary Foster, Parks Liaison Officer February 2012 Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 4 1 Context ............................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Purpose of the Off- Road Biking and Walking Strategy ............................................. 8 1.2 How Walkways and Cycleways Contribute to the Delivery of Community Outcomes .... 8 1.3 A Vision for Off-Road Walkways and Cycleways ...................................................... 8 1.4 Benefits of Walkways and Cycleways ..................................................................... 9 1.5 Statutory Requirements for Walkways and Cycleways .............................................. 9 1.6 Other Document Linkages .................................................................................. 10 1.7 Walkways and Cycleways Covered by Strategy ..................................................... 10 1.8 Future Provision and Development ...................................................................... 10 1.9 Annual Maintenance Costs ................................................................................. 11 1.10 Maps ................................................................................................................ 11 2 Current Provision ......................................................................................... -

Draft Canterbury CMS 2013 Vol II: Maps 6.11

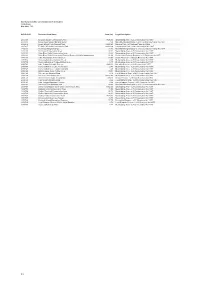

Public conservation land inventory Canterbury Map table 6.11 Conservation Conservation Unit Name Legal Status Conservation Legal Description Description Unit number Unit Area N33022 Gravel Reserve Antrim Hills RALP 1.4 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - N33023 Gravel Reserve Kalkadoon RALP 0.1 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - N33024 Community Buildings Reserve Domett RALP 0.1 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - N33025 Community Buildings Reserve Domett RALP 0.1 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - N33031 Gravel Reserve Darrocks Road RALP 0.6 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - N33043 Landing Place Reserve Gum Tree Gully RALP 6.4 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - N33044 Napenape Scenic Reserve RASRA 52.6 Scenic Reserve - s.19(1)(a) Reserves Act 1977 Priority ecosystem N33045 Conservation Area Pacific Ocean Foreshore Gum Tree Gully CAST 14.5 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 - N33058 Hurunui Marginal Strip CAMSM 5.4 Moveable Marginal Strip - s.24(1) & (2) Conservation Act 1987 - N33061 Crystal Brook Marginal Strip CAMS 1.0 Fixed Marginal Strip - s.24(3) Conservation Act 1987 - N33062 Hurunui Marginal Strip CAMSM 0.1 Moveable Marginal Strip - s.24(1) & (2) Conservation Act 1987 - O33036 Drain Reserve Crystal Brook RALP 3.3 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - O33041 Drain Reserve Crystal Brook RALP 1.2 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - O33044 Quarry Reserve Jed Vale RALP 0.5 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 -

Timaru District Council Minutes of a Meeting of The

TIMARU DISTRICT COUNCIL MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE GERALDINE COMMUNITY BOARD, HELD IN THE MEETING ROOM, GERALDINE LIBRARY/SERVICE CENTRE, TALBOT STREET, GERALDINE ON WEDNESDAY 11 NOVEMBER 2015 AT 7.30PM PRESENT Wayne O’Donnell (Chairperson), Jan Finlayson, Chris Fisher, Jarrod Marsden, McGregor Simpson and Clr Kerry Stevens APOLOGIES An apology for absence was received from Shaun Cleverley IN ATTENDANCE The Mayor (Damon Odey), Group Manager Regulatory Services (Chris English), District Planning Manager (Mark Geddes), Customer Services Manager (Jenny Ensor), Council Secretary (Joanne Brownie) 1 IDENTIFICATION OF URGENT BUSINESS It was agreed to consider an exchange of land at Orari Bridge as urgent business at this meeting. 2 CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The Chairperson reported on duties he had undertaken and meetings he had attended on behalf of the Board since the last meeting including the Geraldine Community Vehicle Trust, Council Standing Committees, a meeting regarding the cycle race coming through Geraldine in January 2016, Go Geraldine regarding the visitor centre, Remembrance Day and unveiling of new plaques at the Geraldine RSA, discussions with the Chief Executive and District Planning Manager and dealing with correspondence. 3 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Proposed McGregor Simpson Seconded Clr Kerry Stevens “That the minutes of the Geraldine Community Board meeting held on 30 September 2015, be confirmed as a true and correct record.” MOTION CARRIED 4 RESOURCE CONSENT 5355 – ORARI GORGE The Board considered a report by the Regulatory Services Manager in response to a request from the previous Board meeting, regarding the Orari Gorge tracks issue. The Group Manager Regulatory Services and the District Planning Manager spoke to the report, further explaining the Timaru District Council’s role in the consenting of the tracks, the limitations within the District Plan as to what action Council could take and steps that are planned to improve the situation. -

Canterbury (Waitaha) CMS 2016 Volume II

Inventory of public conservation land and waters Canterbury Map table 7.12 NaPALIS ID Protected Area Name Area (ha) Legal Description 2805038 Mt Cook Station Conservation Area 8696.03 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 2805043 Mount Cook Station Marginal Strips 7.50 Moveable Marginal Strip - s.24(1) & (2) Conservation Act 1987 2805070 Aoraki Mount Cook National Park 72291.01 National Park - s.4 National Parks Act 1980 2807927 Te Kahui Kaupeka Conservation Park 93103.29 Conservation Park - s.19 Conservation Act 1987 2809166 Richmond Marginal Strips 21.68 Moveable Marginal Strip - s.24(1) & (2) Conservation Act 1987 2809190 Richmond Conservation Area 91.98 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 2809191 Cass River Delta Conservation Area 43.22 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 2809192 Cass River Delta Government Purpose Reserve Wildlife Management 52.34 Government Purpose Reserve - s.22 Reserves Act 1977 2809193 Lake Alexandrina Scenic Reserve 23.58 Scenic Reserve - s.19(1)(a) Reserves Act 1977 2809724 Conservation Area Irishman Creek 4.80 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 2809725 Conservation Area Tekapo Military Area 0.12 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 2809743 Lake Tekapo Scientific Reserve 1010.33 Scientific Reserve - s.21 Reserves Act 1977 2809746 Conservation Area Lake Alexandrina 2.45 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 2809747 Conservation Area Tekapo Township 1.49 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 2809748 Micks Lagoon Conservation Area 19.31 Stewardship -

New Zealand Gazette of Thursday, August 26, 1937

jumb. 58. 2095 81:TPPLE J\!IE NT TO THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE OF THURSDAY, AUGUST 26, 1937. iuh1isgt)) by ~ut!Jority. WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, AUGUST 26, 1937. Tender.s for Inland Mail-service Contracts.-8outh Island, POSTAL DISTRICT OF CHRISTCHURCH. 1938-40, 1. Ashburton and Mayfield: Ashburton to ·Winslow, along Hinds-Winslow and Hinds Swamp Roads to G'eneral Post Office, Maronan, thence Carter's Road to Lismore and May Wellington, :!3rd August, 1937. field, Pet~r's, Blair's, Wright's, South Hinds, Morrow's, EALED tenders will be received at the several Chief Shepherd s Bush, and Moorhouse Roads to Mayfield, S Post-offices in the South Island until noon on Tuesday, Rangitata and Ballantyne's Roads to Ruapuna, the 21st September, 1937, for the conveyance of mails between Cross, Perrin's, Cracraft~ River, Studholme, and the undermentioned places for a period of three years from Chisnall's Roads to Hinds and Ashburton (part rural the 1st January, 1938. delivery), da,ily. 2. Ashburton Railway-station and Post-office, as required. 3. Barry's Bay and VVainui, daily. POSTAL DISTRICT OF BLENHEJM. 4. Kaikoura and Kaikoura Suburban : Kaikoura along Beach, Ludstone, Rorrison's, Hawthorne, :Th1{ount 1. Blenheim and Branch River : Blenheim, W aihopai, Fyffe, Mill, Athenley, and Schoolhouse Roads to Beach Wairau Valley, Hillersden, Birch Hill, and Branch Road, retrace Schoolhouse Road to Athenley Road, River (part rural delivery), thrice weekly. thence to Stack's Corner, along Postman's W'ildc11ess, 2. Blenheim : Delivery of parcels and other packages Kincaid, Parson's, Grange, Bay Paddock, and Kinc,i,id including postmen's overflow bags within borough Roads to Stack's Corner, along Postman's and ]\fount boundaries, as required. -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 20

386 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 20 No. 6 State Highway (Blenheim-lnvercargill via Nelson and No. 73 State Highway (Christchurch-Kumara)~Commencing Greymouth)_JOommencing at Blenheim and proceeding thence at No. 1 State Highway at intersection -of Hansons Lane and 'to Invercargill vfa Renwick, Havelock, Rai Valley, Nelson, Rich Blenheim Road, and proceeding thence to Kumara via Han mond, Brightwater, Wakefield, Belgrove, Spo'Oners Hill, K'Orere, -sons Lane, Ohurch corner, Y·aldhurst, West Mel·ton, Aylesbury, Clark VaUey, Hope Hill, Kawa1irj, Murohison, O'·Sullivans Kirwee, Darfield, Waddington, Sheffield, Springfield, Porters Bridge, Lye'll, Inangahua Junction, Cronadun, Reefiton, Ma Pass, Cass, Bealey, Arthur's Pass, Otira, Jacksons, Wainihi wheraiti Ikamatua, A:haura, Ngahere, Kaiata, Greymouth, nihi, Dillmanstown, Kumara, to Kumara Junction. Paroa, Kumara Junction, Hoki•tika, Kaniere, Rimu, Ross, Harihari, Wataroa, The Forks, Waiho, Weheka, Karangarua, No. 75 State Highway (Christchurch-Akaroa)-Oommencing Bruce Bay, Mahitahi, Paringa River Bridge ~o Lake Par-inga at No. 1 State Highway at Chri~tdhurch and proceeding thence (a distance of approximately 4 miles south of the Paringa •to Akaroa via Halswell, Tai Tapu, M·ortukarara, Kaituna, Bird River bridge). Recommencing at Makarora and proceeding lings Flat, Little River, Hill Top, Barrys Bay, Duvauchelle, via Lake Wanaka, Lake Hawera, and Alberttown to Robinsons Bay, and Takamatua. junction No. 89 St:a.te Highway; <thence via Luggate, Queens berry, L'Owburn, and Kawarau Goiige 'to Queenstown; return No. 77 State Highway (Ashburton - Rakaia Gorge)-,Com ing from Queenstown via Frankton, Kings-ton, Garston, Athol, mencing at No. 1 State Highway at Ashburton and ,proceeding Lumsden, Car,oline, Dipton, Winton, Lochiel, Makarewa, and thence via Racecourse Road to Winchmore and Methven to Waikiwi to Invercargill. -

The New Zealand Gazette 2513

10 NOVEMBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 2513 Ocean Grove, Domain Hall. Sherwood Downs, Hall. Otakou, Public School. Skipton, Hall. PortobeIlo, Public School. Southburn, School. Pukehiki, Public Hall. Springbrook, School. St. Clair- Springburn, School. Forbury Road, Reformed Church Hall. Sutherlands, School Building. Richardson Street, Public School. Tekapo, School. St. Kilda- Te Moana, School. Marlow Street, Musselburgh School. Temuka- Plunket Street, Forbury Raceway Tearooms. Courthouse. Prince Albert Road, Town Hall. Parish Hall. Queen's Drive, Presbyterian Sunday School Hall. Primary School. South Dunedin- Te Ngawai, Social Hall. King Edward Street, Salvation Army Hall. Tinwald- Macandrew Road, Intermediate School. Primary School. Macandrew Road, St. Patrick's Church Hall. Scout and Guide Den. Oxford Street, Forbury School. Totara Valley, Hall. Wesley Street, Methodist Church Hall. Tripp, School. Tainui, Tahuna Road, Tainui School. Twizel, High School. Waverley, Mathieson Street, Grants Braes School. Upper Waitohi, Hall. Waihaorunga, School. Waitohi, Hall. Westerfield, Westerfield-Lagmhor Hall. Willowby, School. South Canterbury Electoral District Winchester, School. Albury, School. Woodbury, School. Alford Forest, Hall. Allandale, Hall. Anama, School. Arundel, Hall. Ashburton- Stratford Electoral District Allenton School. Ahititi, Primary School. Hospital Tutorial Block. Awakino, Primary School. Pipe Band Hall, Creek Road. Bell Block, Primary School. St. Andrew's Hall, Havelock Street. Brixton, Memorial Hall. Ashburton Forks, Mr F. W. Newton's House. Cardiff, Primary School. Bluecliffs, School. Douglas, Primary School. Burkes Pass, Hall. Egmont Village, Primary School. Cannington, School. Fitzroy, Primary School. Carew, School. Frankley School, Tukapa Street, New Plymouth. Cattle Creek, School. Glen Avon- Cave, Public Hall. Alberta Road, Public Hall. Chamberlain, Mr M. A. Fraser's House. Firth Concrete Depot, Devon Road. -

Draft Geraldine Transport Strategy Timaru District Council

Draft Geraldine Transport Strategy Timaru District Council Draft Geraldine Transport Strategy Timaru District Council Quality Assurance Information Prepared for: Timaru District Council Job Number: TDC-J016 Prepared by: Stephen Carruthers, Associate Transportation Planner Reviewed by: Dave Smith, Technical Director Date issued Status Approved by Name 13 June 2019 V1.1 Draft for client review Dave Smith 5 November 2020 V1.2 Second draft with client feedback Dave Smith 21 June 2019 V2 for Community Board Dave Smith This document has been produced for the sole use of our client. Any use of this document by a third party is without liability and you should seek independent advice. © Abley Limited 2018. No part of this document may be copied without the written consent of either our client or Abley Limited. Refer to http://www.abley.com/output-terms-and-conditions-1-0/ for output terms and conditions. T +64 9 486 0898 (Akld) Auckland Christchurch www.abley.com T +64 3 377 4703 (Chch) Level 8, 57 Fort Street Level 1, 137 Victoria Street E [email protected] PO Box 911336 PO Box 25350 Auckland 1142 Christchurch 8144 New Zealand New Zealand Executive Summary Geraldine is located midway along the Inland Scenic Route between Christchurch and Queenstown. This presents an opportunity for Geraldine to maximise the economic opportunities from passing through tourists. The local economy is also founded on the agricultural industry which relies on an efficient transport system for the import and export of its products. The transport system is therefore pivotal to the success of Geraldine. To extract the most from the transport system, Timaru District Council engaged Abley to develop a transport strategy that is built on an understanding of the local context, problems and the desires of the local community. -

Geraldine Community Board Inaugural Meeting

GERALDINE COMMUNITY BOARD INAUGURAL MEETING Commencing at 7.30pm on Wednesday 13 November 2013 Geraldine Library/Service Centre Talbot Street GERALDINE TIMARU DISTRICT COUNCIL Notice is hereby given that the Inaugural Meeting of the Geraldine Community Board will be held at the Geraldine Library/Service Centre, Talbot Street, Geraldine on Wednesday 13 November 2013, at 7.30pm. LOCAL AUTHORITIES (MEMBERS’ INTERESTS) ACT 1968 Board members are reminded that if you have a pecuniary interest in any item on the agenda, then you must declare this interest and refrain from discussing or voting on this item, and are advised to withdraw from the meeting table. Peter Nixon CHIEF EXECUTIVE GERALDINE COMMUNITY BOARD INAUGURAL MEETING 13 NOVEMBER 2013 AGENDA Item Page No No 1 Apologies 2 1 Declaration by Board Members 3 2 Election of Chairman 4 3 Election of Deputy Chairman 5 4 Appointment of Community Board Representatives to Organisations 6 5 General Explanation by Chief Executive 7 9 Community Board Meeting Dates 8 10 Elected Members’ Allowances and Recovery of Expenses 9 17 Upper Orari Bridge Replacement 10 20 Surveillance Cameras in Geraldine 11 25 Thomas Hobson Trust – Correspondence Received 12 26 Thomas Hobson Trust Fund – Accounts and Applications 13 39 Exclusion of the Public 14 41 Thomas Hobson Trust – Rent Review Details Timaru District Council Geraldine Community Board # 848900 13 November 2013 GERALDINE COMMUNITY BOARD FOR THE INAUGURAL MEETING OF 13 NOVEMBER 2013 Report for Agenda Item No 2 Prepared by - Peter Nixon Chief Executive Declaration by Board Members _______________________________ Those persons who as a result of the elections held during the period commencing on Friday 20 September 2013 and ending on Saturday 12 October 2013, were duly elected as members of the Geraldine Community Board of the Timaru District, will be requested to make and sign declarations as required by the provisions of Clause 14, Schedule 7 of the Local Government Act 2002 – Shaun Cleverley Jan Finlayson Chris Fisher Jarrod Marsden Wayne O’Donnell McGregor Simpson. -

Geraldine Community Board Agenda 11 September 2019

AGENDA Geraldine Community Board Meeting Wednesday, 11 September 2019 Date Wednesday, 11 September 2019 Time 7.30pm Location Geraldine Library and Service Centre File Reference 1279398 Timaru District Council Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the Geraldine Community Board will be held in the Geraldine Library and Service Centre, on Wednesday 11 September 2019, at 7.30pm. Geraldine Community Board Members Clr Wayne O’Donnell (Chairperson), Jarrod Marsden (Deputy Chairperson), Clr Kerry Stevens, Janene Adams, Jan Finlayson, Jennine Maguire, Gavin Oliver Local Authorities (Members’ Interests) Act 1968 Community Board members are reminded that if you have a pecuniary interest in any item on the agenda, then you must declare this interest and refrain from discussing or voting on this item, and are advised to withdraw from the meeting table Bede Carran Chief Executive Geraldine Community Board Meeting Agenda 11 September 2019 Order Of Business 1 Apologies .......................................................................................................................... 5 2 Public Forum ..................................................................................................................... 5 3 Identification of Items of Urgent Business .......................................................................... 5 4 Identification of Matters of a Minor Nature ....................................................................... 5 5 Declaration of Conflicts of Interest ................................................................................... -

Orari-Opihi-Pareora Zone Water Management Committee Meeting

ORARI-OPIHI-PAREORA ZONE WATER MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE MEETING Commencing at 12noon (lunch available from 11.45am) on Monday 14 May 2012 Opuha Dam offices 875 Arowhenua Road Pleasant Point ORARI-OPIHI-PAREORA ZONE WATER MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the Orari-Opihi-Pareora Zone Water Management Committee will be held at the Opuha Dam Ltd premises, Arowhenua Road, on Monday 14 May 2012, at 12noon. ** A working lunch will be available from 11.45am LOCAL AUTHORITIES (MEMBERS’ INTERESTS) ACT 1968 Committee members are reminded that if you have a pecuniary interest in any item on the agenda, then you must declare this interest and refrain from discussing or voting on this item, and are advised to withdraw from the meeting table. ORARI-OPIHI-PAREORA ZONE WATER MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 14 MAY 2012 AGENDA Time Page 1 Apologies 2 Page 1 Confirmation of Minutes 2 April 2012 Meeting Correspondence Outward - Page 5 Submission on ECan Long Term Plan Page 6 Submission to Upper Waitaki Zone committee 3 Inward – Reply to submission on the Upper Waitaki Zone Page 7 Implementation Programme 4 Page 9 Exclusion of the Public 5 12.10pm Pareora Flow Plan – Vin Smith, ECan 6 Page 10 Readmittance of the Public 7 Public forum 8 12.30pm Regional LAWP briefing – Vin Smith, ECan paper 9 1.30pm separately Water Use Report – Judith Earl-Goulet attached 10 2pm BREAK 11 2.20pm Briefing on Waitaki Plan – Christina Robb Regional Infrastructure update – Dennis 12 2.35pm Page 11 Jamieson 13 2.50pm Regional Committee update – John O’Neill OWT floodplain