20-01 Date: August 14, 2020 Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Review Opinion Procedure Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

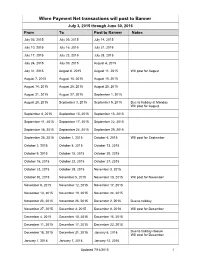

Transactions Posted to Pathway

When Payment Net transactions will post to Banner July 3, 2015 through June 30, 2016 From To Post to Banner Notes July 03, 2015 July 09, 2015 July 14, 2015 July 10, 2015 July 16, 2015 July 21, 2015 July 17, 2015 July 23, 2015 July 28, 2015 July 24, 2015 July 30, 2015 August 4, 2015 July 31, 2015 August 6, 2015 August 11, 2015 Will post for August August 7, 2015 August 13, 2015 August 18, 2015 August 14, 2015 August 20, 2015 August 25, 2015 August 21, 2015 August 27, 2015 September 1, 2015 August 28, 2015 September 3, 2015 September 9, 2015 Due to holiday at Monday Will post for August September 4, 2015 September 10, 2015 September 15, 2015 September 11, 2015 September 17, 2015 September 22, 2015 September 18, 2015 September 24, 2015 September 29, 2015 September 25, 2015 October 1, 2015 October 6, 2015 Will post for September October 2, 2015 October 8, 2015 October 13, 2015 October 9, 2015 October 15, 2015 October 20, 2015 October 16, 2015 October 22, 2015 October 27, 2015 October 23, 2015 October 29, 2015 November 3, 2015 October 30, 2015 November 5, 2015 November 10, 2015 Will post for November November 6, 2015 November 12, 2015 November 17, 2015 November 13, 2015 November 19, 2015 November 24, 2015 November 20, 2015 November 26, 2015 December 2, 2015 Due to holiday November 27, 2015 December 3, 2015 December 8, 2018 Will post for December December 4, 2015 December 10, 2015 December 15, 2015 December 11, 2015 December 17, 2015 December 22, 2015 December 18, 2015 December 31, 2015 January 6, 2016 Due to holiday closure Will post for December -

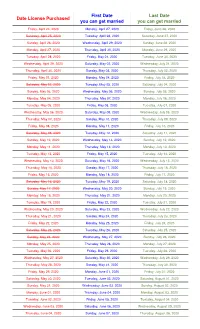

Marriage Valid Dates

First Date Last Date Date License Purchased you can get married you can get married Friday, April 24, 2020 Monday, April 27, 2020 Friday, June 26, 2020 Saturday, April 25, 2020 Tuesday, April 28, 2020 Saturday, June 27, 2020 Sunday, April 26, 2020 Wednesday, April 29, 2020 Sunday, June 28, 2020 Monday, April 27, 2020 Thursday, April 30, 2020 Monday, June 29, 2020 Tuesday, April 28, 2020 Friday, May 01, 2020 Tuesday, June 30, 2020 Wednesday, April 29, 2020 Saturday, May 02, 2020 Wednesday, July 01, 2020 Thursday, April 30, 2020 Sunday, May 03, 2020 Thursday, July 02, 2020 Friday, May 01, 2020 Monday, May 04, 2020 Friday, July 03, 2020 Saturday, May 02, 2020 Tuesday, May 05, 2020 Saturday, July 04, 2020 Sunday, May 03, 2020 Wednesday, May 06, 2020 Sunday, July 05, 2020 Monday, May 04, 2020 Thursday, May 07, 2020 Monday, July 06, 2020 Tuesday, May 05, 2020 Friday, May 08, 2020 Tuesday, July 07, 2020 Wednesday, May 06, 2020 Saturday, May 09, 2020 Wednesday, July 08, 2020 Thursday, May 07, 2020 Sunday, May 10, 2020 Thursday, July 09, 2020 Friday, May 08, 2020 Monday, May 11, 2020 Friday, July 10, 2020 Saturday, May 09, 2020 Tuesday, May 12, 2020 Saturday, July 11, 2020 Sunday, May 10, 2020 Wednesday, May 13, 2020 Sunday, July 12, 2020 Monday, May 11, 2020 Thursday, May 14, 2020 Monday, July 13, 2020 Tuesday, May 12, 2020 Friday, May 15, 2020 Tuesday, July 14, 2020 Wednesday, May 13, 2020 Saturday, May 16, 2020 Wednesday, July 15, 2020 Thursday, May 14, 2020 Sunday, May 17, 2020 Thursday, July 16, 2020 Friday, May 15, 2020 Monday, May 18, 2020 -

August 14, 2020 CHANCELLORS LAWRENCE BERKELEY

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA BERKELEY • DAVIS • IRVINE • LOS ANGELES • MERCED • RIVERSIDE • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO SANTA BARBARA • SANTA CRUZ OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1111 Franklin Street, Oakland, California 94607-5200 August 14, 2020 CHANCELLORS LAWRENCE BERKELEY NATIONAL LABORATORY DIRECTOR VICE PRESIDENT–AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES RE: Revised Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment Policy and Implementing Procedures Dear Colleagues: Today, the new federal Title IX regulations go into effect. Issued by the U.S. Department of Education (“DOE”) on May 6 of this year, the regulations detail how schools across the country must respond to complaints of sexual harassment, including sexual violence. The University identified serious concerns with the regulations when the DOE first proposed them. Despite our advocacy for changes, the DOE retained many of the most problematic parts in the final rules. As the University’s federal funding is conditioned on compliance with the regulations, we will now fully implement them. For the past 100 days, our offices and UC Legal have undertaken the task of revising our processes, resulting in the interim presidential policies issued today by Provost Brown, acting under powers granted by the Regents. Our mandate was to comply with the regulations without compromising the University’s values or the sexual harassment prevention, detection and response efforts so critical to its mission. Our work was aided by a diverse systemwide workgroup we formed in response to the regulations. That workgroup included representatives of the Academic Senate, students and staff, and professionals from the offices most directly involved in resolution processes, including Title IX, Student Conduct, CARE, Respondent Services, Hearing Coordinators, Academic Personnel and Human Resources. -

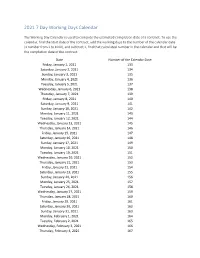

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

FISCAL YEAR 2021 NET MONTH ENDING DISTRIBUTED RATE July

LOCAL GOVERNMENT INVESTMENT POOL HISTORICAL DISTRIBUTED INTEREST RATE FISCAL YEAR 2021 NET MONTH ENDING DISTRIBUTED RATE July 20 0.7433147 August 20 0.6300288 September 20 0.5610540 October 20 0.4106052 November 20 0.3685104 December 20 0.3069768 January 21 February 21 March 21 April 21 May 21 June 21 FISCAL YEAR 2019 NET FISCAL YEAR 2020 NET MONTH ENDING DISTRIBUTED RATE MONTH ENDING DISTRIBUTED RATE July 18 1.9901991 July 19 2.3974434 August 18 2.0210545 August 19 2.4738735 September 18 2.0937608 September 19 2.2970634 October 18 2.1972258 October 19 1.9986782 November 18 2.2590551 November 19 1.9556098 December 18 2.3552189 December 19 1.8937179 January 19 2.4482615 January 20 1.9683736 February 19 2.5446174 February 20 1.7397910 March 19 2.5177344 March 20 1.6567161 April 19 2.5379901 April 20 1.4176876 May 19 2.4827890 May 20 0.9517614 June 19 2.4725547 June 20 0.9223025 FISCAL YEAR 2017 NET FISCAL YEAR 2018 NET MONTH ENDING DISTRIBUTED RATE MONTH ENDING DISTRIBUTED RATE July 16 0.6009023 July 17 1.0686007 August 16 0.5999359 August 17 1.0848660 September 16 0.6060577 September 17 1.1106783 October 16 0.6330251 October 17 1.1539913 November 16 0.6452236 November 17 1.1893335 December 16 0.6850134 December 17 1.2327497 January 17 0.7690972 January 18 1.3754306 February 17 0.8095764 February 18 1.4976310 March 17 0.8556157 March 18 1.5537682 April 17 0.9544760 April 18 1.7345806 May 17 0.9556690 May 18 1.8301165 June 17 1.0426338 June 18 1.9479517 FISCAL YEAR 2015 NET FISCAL YEAR 2016 NET MONTH ENDING DISTRIBUTED RATE MONTH ENDING -

California Community Colleges Health & Wellness Website

August 14, 2020 – COVID-19 Update No. 86 Hartnell College directly contributed to COVID-19 treatment during the pandemic. Nearly 90 Hartnell nursing students participated in patient care at Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital. The college also loaned 13 ventilators from its respiratory care program and donated PPE such as gloves and masks. (Photo courtesy of Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System.) The COVID-19 Special Update publishes on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. STATE AND NATIONAL GUIDANCE/EXECUTIVE ORDERS/NEWS Gov. Gavin Newsom today gave an update on the state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. (All news conferences are streamed live at noon on his Twitter page and the California Governor Facebook page.) You can find more information on California’s COVID-19 website. Among the headlines from today’s update: The governor today focused on schools, saying more than 90 percent of K-12 students in California are likely starting the school year with distance learning. The state’s leader is advocating for rigorous distance education learning, and noted the requirement of access to devices and quality internet connectivity for ALL students. California now has 601,075 confirmed cases of COVID-19, resulting in 10,996 deaths. The number of COVID- related deaths increased by 1.7 percent from Wednesday's total of 10,778. The state has performed 9.5 million COVID-19 tests; the rate of positive tests over the last 14 days is holding steady at 6.2 percent. You can watch today’s update here. (Please note: it begins around the 4:00 mark.) Blame on both sides and now a recess: Americans are waiting on a new economic stimulus — but Congress is on break until Labor Day. -

Fall 2020 Calendar (2021-1)

FALL 2020 CALENDAR (2021-1) Polk State College 2021-1 16-Week Session FASTRACK 1 FASTRACK 2 12-Week Session Session Dates 8/17/20 - 12/9/20 8/17/20 - 10/12/20 10/14/20 - 12/9/20 9/14/20 - 12/9/20 Priority Registration - Students with 50% Complete Monday, April 6, 2020 Monday, April 6, 2020 Monday, April 6, 2020 Monday, April 6, 2020 Registration for Current Students Enrolled in 2020-1 or 2020-2 (including Dual Enrolled) Monday, April 13, 2020 Monday, April 13, 2020 Monday, April 13, 2020 Monday, April 13, 2020 Open Registration for All Students (including new Dual Enrolled students) Monday, June 1, 2020 Monday, June 1, 2020 Monday, June 1, 2020 Monday, June 1, 2020 Faculty Work Days Wed., 8/12/20 - Fri., 8/14/20 Wed., 8/12/20 - Fri., 8/14/20 Tuition Payment Plan (TPP) Enrollment 5/18/20 - 8/17/20 5/18/20 - 8/17/20 5/18/20 - 8/17/20 5/18/20 - 8/17/20 Last Day to Increase TPP Balance Monday, August 17, 2020 Monday, August 17, 2020 Monday, August 17, 2020 Monday, August 17, 2020 Financial Aid Bookstore Purchase Dates 8/7/20 - 8/24/20 8/7/20 - 8/24/20 10/4/20 - 10/21/20 9/4/20 - 9/21/20 - Error-Free FAFSA, Financial Aid Guaranteed Processing Deadline Friday, July 24, 2020 Friday, July 24, 2020 Meeting SAP, Admission Application 100% Complete Fall Convocation for Faculty and Staff Wednesday, August 12, 2020 Wednesday, August 12, 2020 First Flight Freshman Welcome Friday, August 7, 2020 Friday, August 7, 2020 Friday, August 7, 2020 Friday, August 7, 2020 First Flight Freshman Welcome Friday, August 14, 2020 Friday, August 14, 2020 Friday, August -

2021 Summer Term Calendar May 24 Through August 14 Updated April 21, 2021 Fee Payment Deadline: Wednesday May 5 by 1 P.M

2021 Summer Term Calendar May 24 through August 14 Updated April 21, 2021 Fee Payment Deadline: Wednesday May 5 by 1 p.m. Students who have not paid all fees by the fee payment deadline are subject to having their entire course scheduled dropped. Eight Week Full Term First Term May-mester Term (SF) (S1) (SM) (S3) Monday Monday Monday Monday Term Begins May 24 May 24 June 21 May 17 Thursday Thursday Thursday Thursday Last Day to Add on Campus May 27 May 27 June 24 May 20 Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Last Day to Add Online May 29* May 29* June 26* May 22* Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Last Day for 100% Refund May 29* May 29* June 26* May 22* Thursday Thursday Thursday Thursday Last Day to Drop without a “W” on Campus May 27 May 27 June 24 May 20 Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Last Day to Drop without a “W” Online May 29* May 29* June 26* May 22* Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Last Day for 50% Refund June 5* June 5* July 3* May 29* Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Last Day for 25% Refund June 12* June 12* July 10* June 5* Thursday Thursday Thursday Thursday Last Day to Withdraw on Campus July 15 June 17 July 22 June 3 Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Last Day to Withdraw Online July 17* June 19* July 24* June 5* Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Courses End August 14 July 3 August 14 June 19 Sunday Sunday Sunday Tuesday Grades Due by midnight August 15 July 4 August 15 June 22 *A day marked with an asterisk is either a weekend day or holiday and/or the campus is closed. -

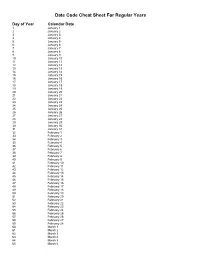

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

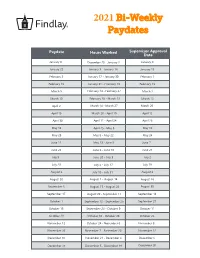

2021 Bi-Weekly Paydates

2021 Bi-Weekly Paydates Paydate Hours Worked Supervisor Approval Date January 8 December 20 - January 2 January 4 January 22 January 3 - January 16 January 15 February 5 January 17 - January 30 February 1 February 19 January 31 - February 13 February 15 March 5 February 14 - February 27 March 1 March 19 February 28 - March 13 March 15 April 2 March 14 - March 27 March 29 April 16 March 28 - April 10 April 12 April 30 April 11 - April 24 April 26 May 14 April 25 - May 8 May 10 May 28 May 9 - May 22 May 24 June 11 May 23 - June 5 June 7 June 25 June 6 - June 19 June 21 July 9 June 20 - July 3 July 2 July 23 July 4 - July 17 July 19 August 6 July 18 - July 31 August 2 August 20 August 1 - August 14 August 16 September 3 August 15 - August 28 August 30 September 17 August 29 - September 11 September 13 October 1 September 12 - September 25 September 27 October 15 September 26 - October 9 October 11 October 29 October 10 - October 23 October 25 November 12 October 24 - November 6 November 8 November 26 November 7 - November 20 November 22 December 10 November 21 - December 4 December 6 December 24 December 5 - December 18 December 20 2021 Bi-Weekly Paydate/Holiday Paydates January February March April Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 3 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 -

Outagamie County Public Health School District Report August 14, 2020

Outagamie County Public Health School District Report August 14, 2020 COVID-19 Case Data for Outagamie County Public Health Jurisdiction Information provided in this summary includes confirmed COVID-19 cases from July 29 - August 11, 2020, unless otherwise indicated, for persons living in Outagamie County Public Health (OCPH) jurisdiction. School district information is organized by the seven public school districts in Outagamie County. This excludes the Appleton Area School District (AASD) and School District of New London. AASD is served by the Appleton Health Department while over 90% of the New London School District population resides in Waupaca County. Additionally, while the Oneida Nation has their own public health jurisdiction, Oneida cases are included in the Seymour data. Cumulative Data Through 8/12/2020* Testing Metric Value Change from Previous Week Total People Tested: 28396 2063 Positive: 1310 152 Negative: 27086 1911 Cumulative Positive Rate: 4.6% 7 Day Positivity Rate Average: 7.8% *Cumulative data for all of Outagamie County OUTAGAMIE COUNTY TOTAL CONFIRMED CASES 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 4/5 5/3 6/7 7/5 8/2 8/9 3/15 3/22 3/29 4/12 4/19 4/26 5/10 5/17 5/24 5/31 6/14 6/21 6/28 7/12 7/19 7/26 1 Outagamie County Public Health School District Report August 14, 2020 While new cases continue to vary from day to day, the 14- and 30-day trends are increasing. *These two charts include all cases in Outagamie County New Positive Cases (Last 14 Days) 35 29 30 28 28 26 25 24 24 25 23 22 20 19 16 16 15 11 11 Positive Case -

Health Sciences Summer 2021 Semester Important Dates and Course Drop Refund Schedule

Health Sciences Summer 2021 Semester Important Dates and Course Drop Refund Schedule 2021 Full Term Session Session A Session B Summer 16 Weeks 15 Weeks 14 Weeks 10 Weeks 8 Weeks 8 Weeks Calendar April 26 - August 14 May 3 - August 15 May 17 - August 21 May 17 - July 24 April 26 - June 19 June 21 - August 14 Class Begin Monday, April 26 Monday, May 3 Monday, May 17 Monday, May 17 Monday, April 26 Monday, June 21 Withdraw Period Begins May 24 May 17 June 14 May 31 May 10 July 5 *Memorial Day (No Class) Monday, May 31 Last Day to Withdraw via Gweb June 4 May 30 July 25 June 13 May 23 July 18 Graduation Application Due for Thursday, July 1 Summer 2021 *Independence Day Monday, July 5 (Univeristy Closed) Classes End August 14 August 15 August 21 July 24 June 19 August 14 *Note: Online students should check with their instructor regarding changes to the class schedule 2021 Full Term Session Session A Session B Summer 16 Weeks 15 Weeks 14 Weeks 10 Weeks 8 Weeks 8 Weeks Calendar April 26 - August 14 May 3 - August 15 May 17 - August 21 May 17 - July 24 April 26 - June 19 June 21 - August 14 Before April 26 Before Apri 26 100% 100% April 26-May 2 Before May 3 April 26-May 2 100% 100% 100% Refund May 3-May 9 May 3-May 9 May 3-May 9 100% 100% 70% Schedule May 10-May 16 May 10-May 16 Before May 17 Before May 17 May 10-May 16 60% 100% 100% 100% 50% with W May 17-May 23 May 17-May 23 May 17-May 23 May 17-May 23 40% 60% with W 100% 100% May 24-May 30 May 24-May 30 May 24-May 30 May 24-May 30 20% with W 40% with W 100% 70% May 31-June 6 May 31-June 6 May 31-June 6 20% with W 60% 50% with W June 7-July 13 40% June 14-June 20 Before June 21 20% with W 100% June 21-June 27 100% June 28-July 4 70% July 5-July 11 50% with W *Note: all deadlines are as of 11:59PM Eastern Time on the stated date .