Re-Introduction of Père David's Deer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China

Entropy 2014, 16, 6313-6337; doi:10.3390/e16126313 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China Xixi Chen 1, Tao Hu 1, Fu Ren 1,2,*, Deng Chen 1, Lan Li 1 and Nan Gao 1 1 School of Resource and Environment Science, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (X.C.); [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (N.G.) 2 Key Laboratory of Geographical Information System, Ministry of Education, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +86-27-87664557; Fax: +86-27-68778893. External Editor: Hwa-Lung Yu Received: 20 July 2014; in revised form: 31 October 2014 / Accepted: 26 November 2014 / Published: 1 December 2014 Abstract: Hubei Province is the hub of communications in central China, which directly determines its strategic position in the country’s development. Additionally, Hubei Province is well-known for its diverse landforms, including mountains, hills, mounds and plains. This area is called “The Province of Thousand Lakes” due to the abundance of water resources. Geographical names are exclusive names given to physical or anthropogenic geographic entities at specific spatial locations and are important signs by which humans understand natural and human activities. In this study, geographic information systems (GIS) technology is adopted to establish a geodatabase of geographical names with particular characteristics in Hubei Province and extract certain geomorphologic and environmental factors. -

A Comprehensive Risk Assessment Framework for Inland Waterway Transportation of Dangerous Goods

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article A Comprehensive Risk Assessment Framework for Inland Waterway Transportation of Dangerous Goods Xi Huang 1, Yuanqiao Wen 1,2, Fan Zhang 3,4,*, Zhongyi Sui 3,4 and Xiaodong Cheng 1 1 Intelligent Transportation Systems Research Center, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430063, China; [email protected] (X.H.); [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (X.C.) 2 National Engineering Research Center for Water Transport Safety, Wuhan 430063, China 3 School of Navigation, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430063, China; [email protected] 4 Hubei Key Laboratory of Inland Shipping Technology, Wuhan 430063, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A framework for risk assessment due to inland waterway transportation of dangerous goods is designed based on all possible event types that may be caused by the inland transportation of dangerous goods. The objective of this study is to design a framework for calculating the risks associ- ated with changes in the transportation of dangerous goods along inland waterways. The framework is based on the traditional definition of risk and is designed for sensitive riverside environmental conditions in inland waterways. From the perspective of transportation management, this paper introduced the concept of transportability of dangerous goods and constructed a transportability assessment framework, which consists of a multi-index evaluation system and a single metric model. The result of the assessment is as an auxiliary basis to determine the transportation permit and control intensity of dangerous goods in an inland waterway specific voyage. The methodology is illustrated using a case study of transporting fireworks in the Yangtze River. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. The

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Energy for Sustainable Development 14 (2010) 238–244 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Energy for Sustainable Development Household level fuel switching in rural Hubei Wuyuan Peng a,⁎, Zerriffi Hisham b, Jiahua Pan c a School of Economic Management, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan Campus), 388 Lumo Road, Hongshan District, Wuhan, Zip code 430074, China b Liu Institute for Global Issues, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada c Research Centre for Sustainable Development, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, China article info abstract Article history: The majority of rural residents in China are dependent on traditional fuels, but the quality and quantity of Received 3 July 2010 existing data on the process of fuel switching in rural China are insufficient to have a clear picture of current Accepted 3 July 2010 conditions and a well-grounded outlook for the future. Based on an analysis of a rural household survey data in Hubei province in 2004, we explore patterns of residential fuel use within the conceptual framework of Keywords: fuel switching using statistical approaches. -

An Improved Evaluation Scheme for Performing Quality Assessments of Unconsolidated Cultivated Land

sustainability Article An Improved Evaluation Scheme for Performing Quality Assessments of Unconsolidated Cultivated Land Lina Peng 1,2, Yan Hu 2,3, Jiyun Li 4 and Qingyun Du 1,5,6,* 1 School of Resource and Environmental Science, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] 2 Wuhan Hongfang Real Estate & Land Appraisal. Co, Ltd., Room 508, District, International Headquarters, Han Street, Wuchang District, Wuhan 430061, China; [email protected] 3 School of Logistics and Engineering Management, Hubei University of Economics, 8 Yangqiao Lake Road, Canglongdao Development Zone, Jiangxia District, Wuhan 430205, China 4 School of Urban and Environmental Sciences, Central China Normal University, 152 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] 5 Key Laboratory of GIS, Ministry of Education, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China 6 Key Laboratory of Digital Mapping and Land Information Application Engineering, National Administration of Surveying, Mapping and Geo-information, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079,China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-27-6877-8842; Fax: +86-27-6877-8893 Received: 5 June 2017; Accepted: 21 July 2017; Published: 27 July 2017 Abstract: Socioeconomic factors are extrinsic factors that drive spatial variability. They play an important role in land resource systems and sometimes are more important than that of the natural setting. The study aims to build a comprehensive framework for assessing unconsolidated cultivated land (UCL) in the south-central and southwestern portions of Hubei Province, China, which have not experienced project management and land consolidation, to identify the roles of natural and especially socioeconomic factors. -

Resource Curse” of the Cultivated Land in Main Agricultural Production Regions: a Case Study of Jianghan Plain, Central China

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Spatio-Temporal Differentiation and Driving Mechanism of the “Resource Curse” of the Cultivated Land in Main Agricultural Production Regions: A Case Study of Jianghan Plain, Central China Yuanyuan Zhu, Xiaoqi Zhou , Yilin Gan, Jing Chen and Ruilin Yu * Key Laboratory for Geographical Process Analysis & Simulation Hubei Province, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (Y.G.); [email protected] (J.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-189-8622-9015 Abstract: Cultivated land resources are an important component of natural resources and significant in stabilizing economic and social order and ensuring national food security. Although the research on resource curse has progressed considerably, only a few studies have explored the existence and influencing factors of the resource curse of non-traditional mineral resources. The current study introduced resource curse theory to the cultivated land resources research and directly investigated the county-level relationship between cultivated land resource abundance and economic develop- ment. Meanwhile, the spatiotemporal dynamic pattern and driving factors of the cultivated land curse were evaluated on the cultivated land curse coefficient in China’s Jianghan Plain from 2001 to 2017. The results indicated that the curse coefficient of cultivated land resources in Jianghan Citation: Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gan, Y.; Plain generally shows a downward trend. That is, the curse phenomenon of the cultivated land Chen, J.; Yu, R. Spatio-Temporal resources in large regions did not improve significantly in 2001–2017. -

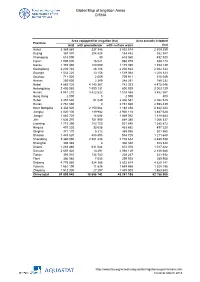

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

One-Dimensional Steady Flow-Sediment Mathematic Models Helius and Their Application in the Three Gorges Project

US-CHINA WORKSHOP ON ADVANCED COMPUTATIONAL MODELLING IN HYDROSCIENCE & ENGINEERING September 19-21, Oxford, Mississippi, USA ONE-DIMENSIONAL STEADY FLOW-SEDIMENT MATHEMATIC MODELS HELIUS AND THEIR APPLICATION IN THE THREE GORGES PROJECT Yue Huang1 and Yuling Huang2 ABSTRACT In order to investigate the sediment problem of the Three Gorges Project (TGP), two 1-D steady flow-sediment mathematic models (i.e., HELIU-1 and HELIU-2) are developed gradually by Changjiang River Scientific Research Institute (CRSRI). Through calculation and verification for in situ measured data of large and medium scale reservoirs and channel reaches downstream of the dams in the Changjiang River Basin, it is found that they can give reasonable results to simulate reservoirs sedimentation and the downstream channel reaches’ deformation due to scour in long time period and long distance. Especially, after completion of TGP the models are also used to predict reservoir sedimentation in the TGP Reservoir (780 km long) and the channel reach (over 1100 km long) downstream of the TGP Dam. The calculated results have been referred by the technical design department of TGP. 1. INTRODUCTION At the beginning of the 1970s, a 1-D steady flow-sediment mathematic model HELIU-1 was developed for studying the sediment problem of the Three Gorges Project (TGP). This model was mainly used to study the scour and deposition of suspended sediment. It simulate reservoir sedimentation well, but it falls short of modeling the scour of river channel. Therefore, the model HELIU-2 was developed in the early 1990s. For HELIU-2, technical problems such as exchange of bed sediment and suspended sediment, river bed deformation and bed sediment composition have been taken into account. -

Distribution Patterns of Yangtze Finless Porpoises in The

bs_bs_banner Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Distribution patterns of Yangtze finless porpoises in the Yangtze River: implications for reserve management X. Zhao1,2,D.Wang1, S. T. Turvey3, B. Taylor4 & T. Akamatsu5,6 1 Key Laboratory of Aquatic Biodiversity and Conservation, Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China 2 China Three Gorges Corporation, Beijing, China 3 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, UK 4 NOAA Fisheries, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, La Jolla, CA, USA 5 NRIFE, Fisheries Research Agency, Kamisu, Ibaraki, Japan 6 Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Tokyo, Japan Keywords Abstract acoustic survey; encounter rate; finless porpoise; habitat preferences; line transect The Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis)isa sampling; moving average; reserve design highly threatened cetacean endemic to the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River that has suffered a dramatic decline in recent decades. We charac- Correspondence terize and quantify recent distribution patterns of porpoises in the Yangtze River Ding Wang, Institute of Hydrobiology, in order to facilitate strategic management of existing in situ cetacean reserves and Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan maximize effective utilization of limited conservation resources. We calculated 430072, China. Tel: +86 27 68780178; porpoise relative abundance (encounter rate) using a 1-km moving average along Fax: +86 27 68780123 the Yangtze main stem based on a combined visual and acoustic survey conducted Email: [email protected]; in 2006. We then evaluated conservation priority areas based on encounter rates [email protected] along the river. High-porpoise density areas (> 0.20 porpoises km-1) cover approximately one-third (33.9%, 599 km) of the survey area and contain approxi- Editor: Karina Acevedo-Whitehouse mately two-thirds of the porpoise population, making them priority areas for Associate Editor: Rob Williams porpoise conservation. -

Spatial and Temporal Changes of Lake Wetlands in Jianghan Plain After the Implementing of ‘Thirty-Six-Word Policy’

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia Environmental Sciences 10 ( 2011 ) 2574 – 2580 2011 3rd International Conference on Environmental Science and Information Application Technology (ESIAT 2011) Spatial and temporal changes of lake wetlands in Jianghan Plain after the implementing of ‘thirty-six-word policy’ Wang Chengchenga, Wang Hongzhi and Xarapat Ablat Faculty of Urban and Environmental Science, Huazhong Normal University, Wuhan, China a [email protected] Abstract After the cataclysm of the Yangtze River in 1998, the State Council put forward the “thirty-six-word policy” for harnessing large rivers and lakes. Jianghan Plain is one of the main areas to get harnessed according to the policy. Based on the CAS land use databases of 1995, 2000, 2005 and 2010, the spatial changes information of lakes in Jianghan Plain were captured and analyzed under the ARCGIS platform or by indexes of landscape ecology. The results show that: From 1995 to 2010, the area of lake wetlands has been grown constantly; Transitions from farmland and unused land to lake were dominant for the increase of lake area, while so were the transitions reversely; Lake wetlands were divided into two categories (lake and pond) to be analyzed according to the area of every lake wetland patch, lakes mainly increased in the area while ponds mainly increased in the number of patches. Ponds are not as curved as lakes in shape and more dispersed than lakes; Lakes became less curved and concentrated with the augment of the area of lake wetlands. The shape of pond wetlands changed little and its distribution became a little concentrated with the increasing number of pond wetlands. -

Elaphurus Davidianus) in China

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 51(6), pp 1-9, 2019. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/2019.51.6.rev1 Review Article Population Status and Research Progress of Père David’s Deer (Elaphurus davidianus) in China Huaisheng Zhang1, Pengfei Li2, Huajun Wen2, Guangming Tian1, Hui Chen1, Lu Zhang1 and Jianqiang Zhu1,* 1 Research Center for health and habitat of Elaphurus Davidianus in Yangtze University, Article Information Jingzhou 434025, China. Received 15 March 2019 2 Revised 11 May 2019 Bureau of Hubei Shishou Milu National Nature Reserve, Shishou 434400, China. Accepted 27 June 2019 Available online 26 August 2019 ABSTRACT Authors’ Contribution JZ designed the study, provided The Milu has been called Père David’s deer (Elaphurus davidianus). It is a unique species in China, which research funding. HZ collecting the has been extinct in China for nearly 200 years. In 1980, the Milu was reintroduced into China and has now data and wrote the manuscript. HW become a first-class protected animal in the country. Moreover, research on the Milu has begun. After 30 and PL Both Huajun Wen and Pengfei Li contributed to the data collection years of breeding and development, the Milu population has formed stable captive or wild populations in and investigation. GT, HC and LZ Beijing, Dafeng, Shishou and Dongting Lake. It has become a typical example of the successful reintro- collected and updated the latest duction of a species. Because of the precision of the information on the Milu in biology and population research progress and population history, the research on Milu has developed rapidly in recent years. -

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of the Critically

Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11307-11323; doi:10.3390/ijms150711307 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Molecular Sciences ISSN 1422-0067 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Article Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of the Critically Endangered Yangtze Finless Porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis) as Revealed by Mitochondrial and Microsatellite DNA Minmin Chen 1,2, Jinsong Zheng 1,*, Min Wu 1,2, Rui Ruan 1,2, Qingzhong Zhao 1 and Ding Wang 1,* 1 The Key Laboratory of Aquatic Biodiversity and Conservation of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Hydrobiology of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430072, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.W.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (Q.Z.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China * Authors to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (D.W.); Tel.: +86-27-6878-0178 (D.W.); Fax: +86-27-6878-0123 (D.W. & J.Z.). Received: 27 January 2014; in revised form: 8 May 2014 / Accepted: 9 May 2014 / Published: 25 June 2014 Abstract: Ecological surveys have indicated that the population of the critically endangered Yangtze finless porpoise (YFP, Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis) is becoming increasingly small and fragmented, and will be at high risk of extinction in the near future. Genetic conservation of this population will be an important component of the long-term conservation effort. We used a 597 base pair mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) control region and 11 microsatellite loci to analyze the genetic diversity and population structure of the YFP. -

Are River Protected Areas Sufficient for Fish Conservation?

Xie et al. BMC Ecol (2019) 19:42 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-019-0258-4 BMC Ecology RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Are river protected areas sufcient for fsh conservation? Implications from large-scale hydroacoustic surveys in the middle reach of the Yangtze River Xiao Xie1,2, Hui Zhang1,2, Chengyou Wang2, Jinming Wu2, Qiwei Wei1,2* , Hao Du1,2, Junyi Li2 and Huan Ye2 Abstract Background: The Yangtze River is the third largest river in the world and sufers from extensive anthropogenic impacts. The fshes in the Yangtze River are essential for the sustainable development of freshwater fsheries and the conservation of aquatic biodiversity in China. However, the fshery resources in the Yangtze River Basin have shown rapid decline due to various human activities. In recent years, nature reserves and germplasm resource reserves have become important means to protect fshes in the Yangtze River. However, nature reserves and germplasm resource reserves that regard freshwater fshes as the main object of protection are not common and have been rarely studied in China. In this paper, a hydroacoustic method and systematic conservation planning tool (Marxan) were combined to evaluate the efectiveness of reserves based on the spatial and temporal patterns of mature fshes in the middle reach of the Yangtze River (MRYR) from 2010 to 2017. Results: The hydroacoustic survey results indicated that in the longitudinal direction, low densities of mature fsh species were observed in the Jingzhou (S2) and Jianli (S4, S5, S6) sections, whereas high densities of fsh were observed in other sections, such as the Yichang (S1), Chenglingji to Huangsangkou (S7–S12), and Hukou (S15) sec- tions.