Birds of Waterloo and Cedar Falls a Beginner's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predation by Gray Catbird on Brown Thrasher Eggs

March 2004 Notes 101 PREDATION BY GRAY CATBIRD ON BROWN THRASHER EGGS JAMES W. RIVERS* AND BRETT K. SANDERCOCK Kansas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (JWR) Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (BKS) Present address of JWR: Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106 *Correspondent: [email protected] ABSTRACT The gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis) has been documented visiting and breaking the eggs of arti®cial nests, but the implications of such observations are unclear because there is little cost in depredating an undefended nest. During the summer of 2001 at Konza Prairie Bio- logical Station, Kansas, we videotaped a gray catbird that broke and consumed at least 1 egg in a brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) nest. Our observation was consistent with egg predation because the catbird consumed the contents of the damaged egg after breaking it. The large difference in body mass suggests that a catbird (37 g) destroying eggs in a thrasher (69 g) nest might risk injury if caught in the act of predation and might explain why egg predation by catbirds has been poorly documented. Our observation indicated that the catbird should be considered as an egg predator of natural nests and that single-egg predation of songbird nests should not be attributed to egg removal by female brown-headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater) without additional evidence. RESUMEN El paÂjaro gato gris (Dumetella carolinensis) ha sido documentado visitando y rompien- do los huevos de nidos arti®ciales, pero las implicaciones de dichas observaciones no son claras porque hay poco costo por depredar un nido sin defensa. -

Catbird, Gray

Mockingbirds and Thrashers — Family Mimidae 449 Mockingbirds and Thrashers — Family Mimidae Gray Catbird Dumetella carolinensis Though the Gray Catbird breeds west almost to the coast of British Columbia, it is only a rare vagrant to California—the bulk of the population migrates east of the Rocky Mountains. But the species is on the increase: of 107 reports accepted by the California Bird Records Committee 1884–1999, one third were in just the last four years of this interval. Similarly, of the 20 records of the Gray Catbird in San Diego County, 10 have come since initiation of the field work for this atlas in 1997. Migration: Half of San Diego County’s known cat- Photo by Anthony Mercieca birds have been fall migrants, occurring as early as 24 September (1976, one at Point Loma, S7, K. van Vuren, Cabrillo National Monument, Point Loma 11–17 July 1988 Luther et al. 1979). Besides eight fall records from Point (B. and I. Mazin, Pyle and McCaskie 1992) certainly was. Loma, there is one from the Tijuana River valley 7–8 November 1964 (the only specimen, SDNHM 35095), Winter: Three wintering Gray Catbirds have been report- one from a boat 15 miles off Oceanside 26 October 1983 ed from San Diego County, from Balboa Park (R9) (M. W. Guest, Bevier 1990), and two from Paso Picacho 16 December 1972 (P. Unitt) and from Point Loma 7 Campground (M20) 29 October 1988 (D. W. Aguillard, November 1983–13 March 1984 (V. P. Johnson, Roberson Pyle and McCaskie 1992) and 17 November 2002 (T. 1986) and 31 October 1999–21 January 2000 (D. -

Belize), and Distribution in Yucatan

University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Institut of Zoology Ecology of the Black Catbird, Melanoptila glabrirostris, at Shipstern Nature Reserve (Belize), and distribution in Yucatan. J.Laesser Annick Morgenthaler May 2003 Master thesis supervised by Prof. Claude Mermod and Dr. Louis-Félix Bersier CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. Aim and description of the study 2. Geographic setting 2.1. Yucatan peninsula 2.2. Belize 2.3. Shipstern Nature Reserve 2.3.1. History and previous studies 2.3.2. Climate 2.3.3. Geology and soils 2.3.4. Vegetation 2.3.5. Fauna 3. The Black Catbird 3.1. Taxonomy 3.2. Description 3.3. Breeding 3.4. Ecology and biology 3.5. Distribution and threats 3.6. Current protection measures FIRST PART: BIOLOGY, HABITAT AND DENSITY AT SHIPSTERN 4. Materials and methods 4.1. Census 4.1.1. Territory mapping 4.1.2. Transect point-count 4.2. Sizing and ringing 4.3. Nest survey (from hide) 5. Results 5.1. Biology 5.1.1. Morphometry 5.1.2. Nesting 5.1.3. Diet 5.1.4. Competition and predation 5.2. Habitat use and population density 5.2.1. Population density 5.2.2. Habitat use 5.2.3. Banded individuals monitoring 5.2.4. Distribution through the Reserve 6. Discussion 6.1. Biology 6.2. Habitat use and population density SECOND PART: DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS THROUGHOUT THE RANGE 7. Materials and methods 7.1. Data collection 7.2. Visit to others sites 8. Results 8.1. Data compilation 8.2. Visited places 8.2.1. Corozalito (south of Shipstern lagoon) 8.2.2. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Relationship of Anting and Sunbathing to Molting in Wild Birds

RELATIONSHIP OF ANTING AND SUNBATHING TO MOLTING IN WILD BIRDS ELOISE F. lPOTTER AND DORIS C. HAUSER • AviAr• anting has generateda large and somewhatcontroversial body of literature, much of it based upon the behavior of captive or experi- mental birds (e.g. Ivor 1943, Whitaker 1957, Weisbrod 1971), birds treat- ing plumagewith substancesother than ants (recently with mothballs in Dubois 1969 and with lemon oil in Johnson 1971), or single oc- currencesfrom widely scatteredgeographical locations. McAtee (1954) advisedthat in searchingfor a reasonabletheory as to why birds ant only recordsfrom wild birds using ants should be examined. The authors agree with McAtee and further believe that data should be considered comparableonly when taken from a limited geographicalregion (e.g. temperateNorth America in Potter 1970). The literatureon antinghas beenreviewed several times (Groskin 1950, Whitaker 1957, Chisholm1959, Simmons1966, Potter 1970). Principal theoriesare (1) that anting birds "derive sensualpleasure from anting, possiblysexual stimulation" (Whitaker 1957); (2) that ant secretions prevent, remove, or otherwise control ectoparasiteinfestation (Groskin 1950, Dubinin in Kelso and Nice 1963, Simmons1966); (3) that ant secretionsmay be helpful in feather maintenanceby increasingflow of salivafor preening,removing stale preen oil and other lipids,or increasing feather wear resistance(Simmons 1966); and (4) that ant secretions sootheskin irritated by the emergenceof new feathers (Southern 1963, Potter 1970). Only four authors have publisheda dozen or more anting recordsinvolving wild birds usingants and takingplace in or near a single location in temperate North America. These are Brackbill (1948) from Maryland, Groskin(1950) from Pennsylvania,Potter (1970) from North Carolina, and Hauser (1973) also from North Carolina. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

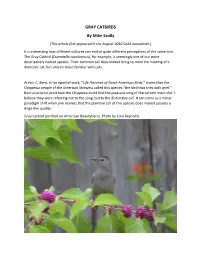

GRAY CATBIRDS by Mike Scully

GRAY CATBIRDS By Mike Scully (This article first appeared in the August 2010 SAAS newsletter.) It is interesting how different cultures can evolve quite different perceptions of the same bird. The Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis), for example, is seemingly one of our more descriptively named species. Their common call does indeed bring to mind the mewing of a domestic cat, but only to those familiar with cats. Arthur C. Bent, in his epochal work, “Life Histories of North American Birds,” states that the Chippewa people of the American Midwest called this species “the bird that cries with grief.” Bent puzzled in print how the Chippewa could find the pleasant song of the catbird mournful. I believe they were referring not to the song, but to the distinctive call. It can come as a minor paradigm shift when one realizes that the plaintive call of this species does indeed possess a dirge-like quality. Gray Catbird perched on American Beautyberry. Photo by Lora Reynolds. Certainly the catbird was familiar to many of the original inhabitants of North America, much as it remains today; an attractive gray bird, slipping low between brush tangles, the frequency of its songs and calls belying any impression of secrecy. The Gray Catbird possesses two attributes that doubtless help it succeed in human-altered landscapes; it prefers dense edge and early successional habitats, and it possesses a faculty for recognizing and rejecting the eggs of the Brown-headed Cowbird. The present breeding range includes the majority of North America, but they are absent from the Far North, the Florida Peninsula, much of the Southwest, the Great Basin and our Pacific Coast. -

Anting Behavior by the White-Bearded Manakin (Manacus Manacus, Pipridae): an Example of Functional Interaction in a Frugivorous Lekking Bird

Biota Neotrop., vol. 10, no. 4 Anting behavior by the White-bearded Manakin (Manacus manacus, Pipridae): an example of functional interaction in a frugivorous lekking bird César Cestari1,2 1Departamento de Zoologia, Programa de Pós-graduação em Zoologia, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” – UNESP, Campus de Rio Claro, CEP 13506-900, Rio Claro, SP, Brasil 2Corresponding author: César Cestari, e-mail: [email protected] CESTARI, C. Anting behavior by the White-bearded Manakin (Manacus manacus, Pipridae): an example of functional interaction in a frugivorous lekking bird. Biota Neotrop. 10(4): http://www.biotaneotropica.org. br/v10n4/en/abstract?short-communication+bn02110042010. Abstract: Behavioral studies of birds have reported several functions for active anting. Maintenance of plumage and prevention from ectoparasites are some examples. In this context, anting by males may be of particular importance in a classical lek mating system, where male-male competition is common and individuals with higher fitness may be more successful at attracting of females. In the present note, I describe the anting behavior of White-bearded Manakin (Manacus manacus) and I relate it to lek breeding and feeding (frugivory) habits of the species. Males used up to seven Solenopsis sp. ants. They rubbed each small ant from 4 to 31 times on undertail feathers until the ants were degraded; ants were not eaten. Males then searched for a new ant in the court. Seeds discarded by males on their individual display courts attract herbivorous ants that are used for anting as a way to maintain feathers and fitness. I hypothesize that anting in White-bearded Manakin may increase the probability of males to attract females to their display courts. -

Records of Anting in Washington and Oregon

28Washington Birds 11:28-34 (2011)Wiles and McAllister RECORDS Of anting by biRDS in WaShingtOn anD OREgOn Gary J. Wiles Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way North, Olympia, Washington 98501 [email protected] Kelly R. McAllister 3903 Foxhall Drive NE, Olympia, Washington 98516 [email protected] Anting is a widespread but infrequently observed stereotypic behavior noted in more than 200 bird species, the vast majority of which are pas- serines (Chisholm 1959, Simmons 1966, 1985, Craig 1999). The behavior occurs in passive and active forms (Simmons 1985). In passive anting, birds spread themselves over an ant source and allow ants to crawl through their plumage. During active anting, ants are gathered and crushed in the bill and deliberately rubbed through the plumage using preening- like motions. In this form, other objects such as millipedes, other insects, snails, fruit, flowers, other plant materials, and mothballs are occasionally substituted for ants (Whitaker 1957, Simmons 1966, Clark et al. 1990, VanderWerf 2005). Anting involves the application of the defensive secre- tions (i.e., formic acid or repugnant anal fluid) of worker ants or other aromatic chemical compounds to the feathers or skin of a bird. The purpose of anting remains unclear. Hypothesized functions include soothing irritated skin associated with feather emergence during molt, general feather maintenance, repelling ectoparasites, inhibiting fungal or bacterial growth, food preparation by removing distasteful sub- stances from prey, and pleasurable sensory stimulation (Simmons 1966, 1985, Potter and Hauser 1974, Ehrlich et al. 1986). Experimental evidence from a few species supports that anting is conducted most often during molting (Lunt et al. -

Pre-Lesson Plan

Pre-Lesson Plan Prior to taking part in the Winged Migration program at Tommy Thompson Park it is recommended that you complete the following lessons to familiarize your students with some of the birds they might see and some of the concepts they will learn during their field trip. The lessons can easily be integrated into your Science, Language Arts, Social Studies and Physical Education programs. Part 1: Amazing Birds As a class, read the provided “Wanted” posters. The posters depict a very small sampling of some of the amazing feats and features of birds. To complement these readings, display the following websites so that students can see some of these birds “up close.” Common Loon http://www.schollphoto.com/gallery/thumbnails.php?album=1 Black-Capped Chickadee http://sdakotabirds.com/species_photos/black_capped_chickadee.htm Ruby-Throated Hummingbird http://www.surfbirds.com/cgi-bin/gallery/search2.cgi?species=Ruby- throated%20Hummingbird Downy Woodpecker http://www.pbase.com/billko/downy_woodpecker Great Horned Owl www.owling.com/Great_Horned.htm When you visit Tommy Thompson Park, you may see chickadees, hummingbirds, and woodpeckers. These birds all breed in southern Ontario. However, you probably will not see a Great Horned Owl, because this specific bird is usually flying around at night. Below is a list of some other birds students might see when they visit Tommy Thompson Park. Have them chose one bird each and write a “Wanted” poster for it, focusing on a cool fact about that bird. Some web sites that will help them get started -

How Birds Combat Ectoparasites

The Open Ornithology Journal, 2010, 3, 41-71 41 Open Access How Birds Combat Ectoparasites Dale H. Clayton*,1, Jennifer A. H. Koop1, Christopher W. Harbison1,2, Brett R. Moyer1,3 and Sarah E. Bush1,4 1Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; 2Current address: Biology Department, Siena College, Loudonville, NY, 12211, USA; 3Current address: Providence Day School, Charlotte, NC, 28270, USA; 4Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Research Center, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA Abstract: Birds are plagued by an impressive diversity of ectoparasites, ranging from feather-feeding lice, to feather- degrading bacteria. Many of these ectoparasites have severe negative effects on host fitness. It is therefore not surprising that selection on birds has favored a variety of possible adaptations for dealing with ectoparasites. The functional signifi- cance of some of these defenses has been well documented. Others have barely been studied, much less tested rigorously. In this article we review the evidence - or lack thereof - for many of the purported mechanisms birds have for dealing with ectoparasites. We concentrate on features of the plumage and its components, as well as anti-parasite behaviors. In some cases, we present original data from our own recent work. We make recommendations for future studies that could im- prove our understanding of this poorly known aspect of avian biology. Keywords: Grooming, preening, dusting, sunning, molt, oil, anting, fumigation. INTRODUCTION 2) Mites and ticks (Acari): many families [6-9]. As a class, birds (Aves) are the most thoroughly studied 3) Leeches: four families [10]. group of organisms on earth. -

A Resume of Anting, with Particular Reference to A

A RESUMI? OF ANTING, WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO A CAPTIVE ORCHARD ORIOLE BY LOVIE M. WHITAKER INCE Audubon (1831:7) wrote of Wild Turkeys (Meleugris gallopuvo) S rolling in “deserted” ants ’ nests (Allen, 1946)) and Gosse (1847:225) reported Tinkling Grackles (Q uiscalus niger) in nature anointing themselves with lime fruits (Chisholm, 1944), an extensive literature on the anting ac- tivities of birds has slowly evolved. The complete bibliography of anting probably would approximate 250 items, yet the purpose of the behavior re- mains unexplained. Anting may be defined as the application of foreign substances to the plum- age and possibly to the skin. These substances may be applied with the bill, or the bird may “bathe” or posture among thronging ants which invest its plumage. Among numerous explanations for the use of ants are these: (1) the bird wipes off ant acid, preparatory to eating the ant; (2) ants prey upon, and their acids repel, ectoparasites; (3) ant acids have tonic or medicinal effects on the skin of birds; (4) odor of ants attracts birds, much as dogs are drawn to ordure or cats to catnip; (5) an t s intoxicate the bird or give it unique pleasurable effects; (6) ant substances on the plumage, irradiated by sun- light, produce vitamin D, which the bird ingests during preening; (7) the bird enjoys the movement of insects in its plumage; (8) ant substances pre- vent over-drying of feather oils or give a proper surface film condition to the feathers. For discussions of these possibilities, see Chisholm (1944, 1948: 163-175)) Adlersparre (1936)) IJ zen d oorn (1952~)) Eichler (1936~)) Klein- Schmidt (in Stresemann, 1935b), L ane (1951:163-177)) Kelso (1946, 1949, 1950a, 19506, 1955 :37-39)) Brackbill (1948)) G6roudet (1948), Groskin (1950)) and McAtee (1938).