Players of the Caliber of Howie Long Are Supposed to Be Found in the First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 10-Season Snapshot of NCAA Power Five Head Coaching Hires

24 SEPTEMBER 2020 Field Studies: A 10-Season Snapshot of NCAA Power Five Head Coaching Hires Volume 2 Issue 1 Preferred Citation: Brooks, S.N., Gallagher, K.L., Brenneman, L., Lofton, R. (2020). Field Studies: A 10-Year Snapshot of NCAA Power Five Coaching Hires. Retrieved from Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University (Working Paper Series Volume 2 Issue 1): https://globalsport.asu.edu/resources/field-studies-10-season-snapshot-ncaa- power-five-head-coaching-hires. The Global Sport Institute would like to give special thanks to Kenneth L. Shropshire and Dr. Harry Edwards for reviewing and giving feedback on early drafts of the report. Abstract The purpose of this report is to explore and describe coach hiring and firing trends at the highest collegiate levels. We sought to explore head coach hiring patterns over the past 10 seasons in the Power Five conferences. All data presented have been gathered from publicly accessible sources, such as news articles and press releases, that report on coaches’ entrances into and exits from coaching positions. Trends in hiring and firing related to race are examined, along with patterns related to coaching pipelines and pathways. Implications for future research and need for data-driven policy are discussed. Introduction Tom Fears (New Orleans Saints) was the first Latino American head coach in the NFL (1967), and Joe Kapp was the first Latino American NCAA Division 1-A coach at a predominantly White program (1982, University of California-Berkeley). Tom Flores (Oakland Raiders) was the first Latino and Coach of Color in the NFL’s modern era (after the 1970 NFL-AFL merger). -

Nfl Releases Tight Ends and Offensive Linemen to Be Named Finalists for the ‘Nfl 100 All-Time Team’

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Alex Riethmiller – 310.840.4635 NFL – 12/9/19 [email protected] NFL RELEASES TIGHT ENDS AND OFFENSIVE LINEMEN TO BE NAMED FINALISTS FOR THE ‘NFL 100 ALL-TIME TEAM’ 18 Offensive Linemen and 5 Tight Ends to be Named to All-Time Team Episode 4 of ‘NFL 100 All-Time Team’ Airs on Friday, December 13 at 8:00 PM ET on NFL Network Following the reveal of the defensive back and specialist All-Time Team class last week, the NFL is proud to announce the 40 offensive linemen (16 offensive tackles; 15 guards; 9 centers) and 12 tight ends that are finalists for the NFL 100 All-Time Team. 39 of the 40 offensive linemen finalists have been enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The 12 finalists at tight end include eight Pro Football Hall of Famers and combine for 711 career receiving touchdowns. Episode three will also reveal four head coaches to make the NFL 100 All-Time Team. The NFL100 All-Time Team airs every Friday at 8:00 PM ET through Week 17 of the regular season. Rich Eisen, Cris Collinsworth and Bill Belichick reveal selections by position each week, followed by a live reaction show hosted by Chris Rose immediately afterward, exclusively on NFL Network. From this group of finalists, the 26-person blue-ribbon voting panel ultimately selected seven offensive tackles, seven guards, four centers and five tight ends to the All-Time Team. The NFL 100 All-Time Team finalists at the offensive tackle position are: Player Years Played Team(s) Bob “The Boomer” Brown 1964-1968; 1969-1970; 1971- Philadelphia Eagles; Los Angeles 1973 Rams; Oakland Raiders Roosevelt Brown 1953-1965 New York Giants Lou Creekmur 1950-1959 Detroit Lions Dan Dierdorf 1971-1983 St. -

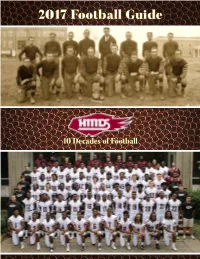

2017 Football Guide

Front cover 2017 Football Guide 10 Decades of Football You cover the endzone. We’ll cover everything else. It takes a real team effort to protect what counts. That’s why Farm Bureau Insurance ®* has a home team of local agents ready to provide all the coverage you need, whether it’s Home, Life, Auto, or Health. Get Real insurance. Get Farm Bureau Insurance®*. Real service. Real people. www.sfbli.com MSMLPR40005 *Mississippi Farm Bureau Casualty Insurance Co. | *Southern Farm Bureau Life Insurance Co., Jackson, MS The Trusty Company, Inc. Employee Benefit Plans Independent Insurance Brokers 601.933.9510 [email protected] Hinds Community College 2010 Alumni Service Award Recipient, 2014 Sports Hall of Fame Inductee & President of the Athletic Rick Trusty Alumni Chapter 2017 HINDS COMMUNITY COLLEGE FOOTBALL WELCOME DR. CLYDE MUSE • PRESIDENT DEAR VISITORS: On behalf of the Board of Trustees and the entire Hinds family, I am pleased to welcome you to Hinds Community College, where you will find a personal and friendly atmosphere. For more than 100 years our focus has been on providing a quality education for all who desired one. We make every effort to provide programs and services that enable students to be successful. The college’s athletic program is just one extension of the comprehensive academic, career and technical instruction offered at Hinds. Athletics complement a strong instructional base that provides educational opportunities of the highest caliber. As a sports enthusiast, I’m proud of the accomplishments of our student athletes, both while they are here and wherever their path may lead. -

North America's Charity Fundraising

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” BW Unlimited is proud to provide this incredible list of hand signed Sports Memorabilia from around the U.S. All of these items come complete with a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) from a 3rd Party Authenticator. From Signed Full Size Helmets, Jersey’s, Balls and Photo’s …you can find everything you could possibly ever want. Please keep in mind that our vast inventory constantly changes and each item is subject to availability. When speaking to your Charity Fundraising Representative, let them know which items you would like in your next Charity Fundraising Event: California Autographed Sports Memorabilia Inventory Updated 10/04/2013 California Angels 1. Rod Carew California Angels Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $380.00 2. Wally Joyner Autographed MLB Baseball (BWU001-02) $175.00 3. Wally Joyner Autographed Big Stick Bat With His Name Printed On The Bat (BWU001-02) $201.00 4. Wally Joyner California Angels Autographed Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $305.00 5. Autographed Don Baylor Baseball Inscribed "MVP 1979" (BWU001- 02) $150.00 6. Mike Witt Autographed MLB Baseball Inscribed "PG 9/30/84" (BWU001-02) $175.00 LA Dodgers 1. Dusty Baker Los Angeles Dodgers Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $285.00 2. Autographed Pedro Guerrero Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $265.00 3. Autographed Pedro Guerrero MLB Baseball (BWU001-02) $150.00 4. Autographed Orel Hershiser Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $325.00 5. Autographed Orel Hershiser Baseball Inscribed 88 WS MVP and 88 WS Cy Young (BWU001-02) $190.00 6. -

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 -

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1960 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1960 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. BALTIMORE 6-6 CHICAGO 5-6-1 CLEVELAND 8-3-1 DALLAS (N) 0-11-1 Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Willard Dewveall Wide Receiver: Ray Renfro Wide Receiver: Billy Howton Jim Mutscheller Jim Dooley Rich Kreitling Fred Dugan (ET) Tackle: Jim Parker (G) Angelo Coia TC Fred Murphy Frank Clarke George Preas (G) Bo Farrington Leon Clarke (ET) Dick Bielski OC Sherman Plunkett Harlon Hill A.D. Williams Dave Sherer PA Guard: Art Spinney Tackle: Herman Lee (G-ET) Tackle: Dick Schafrath (G) Woodley Lewis Alex Sandusky Stan Fanning Mike McCormack (DT) Tackle: Bob Fry (G) Palmer Pyle Bob Wetoska (G-C) Gene Selawski (G) Paul Dickson Center: Buzz Nutter (LB) Guard: Stan Jones (T) Guard: Jim Ray Smith(T) Byron Bradfute Quarterback: Johnny Unitas Ted Karras (T) Gene Hickerson Dick Klein (DT) -

North America's Charity Fundraising

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” Hand Signed Guitars (signed on the Pic Guard) Cost to Non Profit: $1,500.00 Suggested Retail Value: $3,100.00 plus 1. Aerosmith 2. AC/DC 3. Bon Jovi 4. Bruce Springsteen 5. Dave Matthews 6. Eric Clapton 7. Guns N’ Roses 8. Jimmy Buffett 9. Journey 10. Kiss 11. Motely Crue 12. Neil Young 13. Pearl Jam 14. Prince 15. Rush 16. Robert Plant & Jimmy Page 17. Tom Petty 18. The Police 19. The Rolling Stones 20. The Who 21. Van Halen 22. ZZ Top BW Unlimited, llc. www.BWUnlimited.com Page 1 NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” Hand Signed Custom Framed & Matted Record Albums Premium Design Award Style with Gold/ Platinum Award Album Cost to Non Profit: $1,300.00 Gallery Retail Price: $4,200.00 - Rolling Stones & Pink Floyd - $1,600.00 - Gallery Price - $3,700.00 Standard Design with original vinyl Cost to Non Profit: $850.00 Gallery Retail Price: $2,800.00 - Rolling Stones & Pink Floyd - $1,100.00 Gallery Price - $3,700.00 BW Unlimited, llc. www.BWUnlimited.com Page 2 NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” Lists of Available Hand Signed Albums: (Chose for framing in the above methods): 1. AC/DC - Back in Black 42. Guns N' Roses - Use your Illusion II 2. AC/DC - For those about to Rock 43. Heart - Greatest Hits 3. Aerosmith - Featuring "Dream On" 44. Heart - Little Queen 4. Aerosmith - Classics Live I 45. Jackson Browne - Running on Empty 5. Aerosmith - Draw the Lin 46. -

Oakland Raiders Press Release

OAKLAND RAIDERS PRESS RELEASE Feb. 6, 2016 For Immediate Release Former Raiders QB Ken Stabler Elected into Pro Football Hall of Fame ALAMEDA, Calif. – Former Raiders QB Ken Stabler was elected for enshrinement into the Pro Football Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2016, the Pro Football Hall of Fame announced Saturday at the Fifth Annual NFL Honors from the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium in San Francisco, Calif. Stabler, who was nominated by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Senior Committee, joins Owner Edward DeBartolo, Jr., Coach Tony Dungy, QB Brett Favre, LB/DE Kevin Greene, WR Marvin Harrison, T Orlando Pace and G Dick Stanfel to make up the Class of 2016 that will be officially enshrined into the Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio on Aug. 6, 2016. With Stabler entering the Hall of Fame, an illustrious 25 Raiders have now been selected for induction into the Hall of Fame. Below is the updated list: Name Pos. Seasons Inducted Ron Mix T 1971 1979 Jim Otto C 1960-1974 1980 George Blanda QB/K 1967-1975 1981 Willie Brown CB 1967-1978 1984 Gene Upshaw G 1967-1982 1987 Fred Biletnikoff WR 1965-1978 1988 Art Shell T 1968-1982 1989 Ted Hendricks LB 1975-1983 1990 Al Davis Owner 1963-2011 1992 Mike Haynes CB 1983-1989 1997 Eric Dickerson RB 1992 1999 Howie Long DE 1981-1993 2000 Ronnie Lott S 1991-1992 2000 Dave Casper TE 1974-1980, 1984 2002 Marcus Allen RB 1982-1992 2003 James Lofton WR 1987-1988 2003 Bob Brown OT 1971-1973 2004 John Madden Head Coach 1969-1978 2006 Rod Woodson S 2002-2003 2009 Jerry Rice WR 2001-2004 2010 Warren Sapp DL 2004-2007 2013 Ray Guy P 1973-1986 2014 Tim Brown WR 1988-2003 2015 Ron Wolf Executive 1963-74, 1979-89 2015 Ken Stabler QB 1970-79 2016 OAKLAND RAIDERS PRESS RELEASE Ken Stabler played 15 NFL seasons from 1970-84 for the Oakland Raiders, Houston Oilers and New Orleans Saints. -

2016 EAGLES FOOTBALL GUIDE You Cover the Endzone

Front cover 2016 EAGLES FOOTBALL GUIDE You cover the endzone. We’ll cover everything else. It takes a real team effort to protect what counts. That’s why Farm Bureau Insurance ®* has a home team of local agents ready to provide all the coverage you need, whether it’s Home, Life, Auto, or Health. Get Real insurance. Get Farm Bureau Insurance®*. Real service. Real people. www.sfbli.com MSMLPR40005 *Mississippi Farm Bureau Casualty Insurance Co. | *Southern Farm Bureau Life Insurance Co., Jackson, MS 2016 FOOTBALL WELCOME DR. CLYDE MUSE • PRESIDENT DEAR VISITORS: On behalf of the Board of Trustees and the entire Hinds family, I am pleased to welcome you to Hinds Community College, where you will find a quality education with a personal and friendly approach at a reasonable cost. The focus of our college is on the student, and we make every effort to provide programs and services that enable students to be successful. We are extremely pleased with the graduation/completion rate of our student-athletes. Among those working hard for the betterment of the college are members of the coaching staff who prepare their teams for this athletic event. Also to be commended are the band, Hi-Steppers, cheerleaders and their sponsors, the athletic director and the student-athletes. We are particularly pleased to have parents, students and alumni here. We thank you for your support. We hope you enjoy the game and continue to take an interest in the activities at Hinds. The college’s athletic program is just one extension of the comprehensive academic, career and technical instruction offered at Hinds. -

Pushing Weight André Douglas Pond Cummings University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H

University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law Masthead Logo Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives Faculty Scholarship 2008 Pushing Weight andré douglas pond cummings University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation andré douglas pond cummings, Pushing Weight, 33 T. Marshall L. Rev. 95 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUSHING WEIGHT andr6 douglas pond cummings" I. INTRODUCTION The plight of the black athlete in United States professional and collegiate sports reflects a historical road burdened by strident discrimination, yielding assimilation and gleeful exploitation.' As African American athletes in the 1950's began to enter the lineups of storied professional sports clubs, they did so only under the strict conditions placed upon them by the status quo white male dominated regime.2 Often the very terms of black athlete participation required a rigid commitment to "covering" racial identity and outright suppression of self.3 Once African American athletes burst onto the * Professor of Law, West Virginia University College of Law. J.D., 1997, Howard University School of Law. I wish to express appreciation to Texas Southern University, Thurgood Marshall School of Law for inviting me to participate in its exceptional Johnnie Cochran Symposium held November 2, 2007. -

111-113N116 Oakland.Qxd:Oakland Raiders-03R.Qxd

OAKLAND RAIDERS CLUB OFFICIALS COACHING HISTORY Owner: Mark Davis Oakland 1960-1981 General Manager: Reggie McKenzie Los Angeles 1982-1994 Director – Football Administration: (455-381-11) Tom Delaney Records include postseason games Director – Player Personnel: 1960-61 Eddie Erdelatz* .............6-10-0 Joey Clinkscales 1961-62 Marty Feldman**..........2-15-0 Director – College Scouting: 1962 Red Conkright .................1-8-0 Shaun Herock 1963-65 Al Davis ......................23-16-3 Scouting Coordinator: Teddy Atlas 1966-68 John Rauch ................35-10-1 Pro Scouts: Von Hutchins, Larry Marmie, 1969-1978 John Madden............112-39-7 Dane Vandernat 1979-1987 Tom Flores ..................91-56-0 College Scouts: Calvin Branch, Zack 1988-89 Mike Shanahan***........8-12-0 Crockett, Brad Kaplan, Mickey Marvin, 1989-1994 Art Shell......................56-41-0 David McCloughan, Raleigh McKenzie, 1995-96 Mike White..................15-17-0 American Football Conference Trey Scott 1997 Joe Bugel......................4-12-0 West Division Head Athletic Trainer: H. Rod Martin 1998-2001 Jon Gruden.................40-28-0 Team Colors: Silver and Black Team Orthopedist: Dr. Warren King 2002-03 Bill Callahan ................17-18-0 1220 Harbor Bay Parkway Equipment Manager: Bob Romanski 2004-05 Norv Turner...................9-23-0 Alameda, California 94502 Video Director: Dave Nash 2006 Art Shell........................2-14-0 Telephone: (510) 864-5000 Assistant to Head Coach: Tom Jones 2007-08 Lane Kiffin**** ............5-15-0 Director – Media Relations: Zak Gilbert 2008-2010 Tom Cable...................17-27-0 2013 SCHEDULE Director – Player Engagement: 2011 Hue Jackson...................8-8-0 PRESEASON Lamonte Winston 2012 Dennis Allen..................4-12-0 Aug. 9 Dallas................................7:00 Director – Team Security: Fred Formosa * Released after two games in 1961 Aug. -

Tigers in the Draft

Tigers in the Draft NO. NAME, POSITION ROUND TEAM 1949 AAFC 1961 AFL INTRO 1936 21 Albin (Rip) Collins, B 3 Cleveland Bo Strange, C 3 Denver Abe Mickal, B 6 Detroit THIS IS LSU 1950 1962 NFL TIGERS 1937 Al Hover, G 14 Chi. Bears Wendell Harris, B 1 Baltimore Marvin (Moose) Stewart, C 2 Chi. Bears Zollie Toth, B 4 NY Bulldogs Fred Miller, T 7 Baltimore COACHES Gaynell (Gus) Tinsley, E 2 Chi. Cardinals Melvin Lyle, E 10 NY Bulldogs Tommy Neck, B 18 Chicago REVIEW Ebert Van Buren, B 8 NY Giants Earl Gros, B 1 Green Bay 1939 Ray Collins, T 3 San Francisco Jimmy Field, B 16 Green Bay HISTORY Eddie Gatto, T 5 Cleveland Roy Winston, G 4 Minnesota LSU Dick Gormley, C 20 Philadelphia 1951 Billy Joe Booth, T 13 New York Kenny Konz, B 1 Cleveland 1940 Jim Shoaf, G 10 Detroit 1962 AFL Ken Kavanaugh Sr., E 2 Chi. Bears Albin (Rip) Collins, B 2 Green Bay Tommy Neck, HB 20 Boston Young Bussey, B 18 Chi. Bears Joe Reid, C 13 LA Rams Jimmy Field, QB 26 Boston Billy Baggett, B 22 LA Rams Earl Gros, FB 2 Houston 1941 Ebert Van Buren, B 1 Philadelphia Bob Richards, T 32 Oakland Leo Barnes, T 20 Cleveland Y.A. Tittle, QB 1 San Francisco Roy Winston, G 6 San Diego J.W. Goree, G 12 Pittsburgh Wendell Harris, HB 7 San Diego 1952 1943 Jim Roshto, B 12 Detroit 1963 NFL Bill Edwards, G 29 Chi. Cardinals George Tarasovic, C 2 Pittsburgh Dennis Gaubatz, LB 8 Detroit Willie Miller, G 30 Cleveland Rudy Yeater, T 13 San Francisco Buddy Soefker, B 18 Los Angeles Percy Holland, G 22 Detroit Jess Yates, E 20 San Francisco Gene Sykes, B 8 Philadelphia Walt Gorinski, B 17 Philadelphia Chet Freeman, B 23 Texas Jerry Stovall, B 1 St.