(Ordovician) of Central Kentucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanical Stratigraphic Controls on Natural Fracture Spacing and Penetration

Journal of Structural Geology 95 (2017) 160e170 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsg Mechanical stratigraphic controls on natural fracture spacing and penetration * Ronald N. McGinnis a, , David A. Ferrill a, Alan P. Morris a, Kevin J. Smart a, Daniel Lehrmann b a Department of Earth, Material, and Planetary Sciences, Southwest Research Institute, 6220 Culebra Road, San Antonio, TX 78238-5166, USA b Geoscience Department, Trinity University, One Trinity Place, San Antonio, TX 78212, USA article info abstract Article history: Fine-grained low permeability sedimentary rocks, such as shale and mudrock, have drawn attention as Received 20 July 2016 unconventional hydrocarbon reservoirs. Fracturing e both natural and induced e is extremely important Received in revised form for increasing permeability in otherwise low-permeability rock. We analyze natural extension fracture 21 December 2016 networks within a complete measured outcrop section of the Ernst Member of the Boquillas Formation Accepted 7 January 2017 in Big Bend National Park, west Texas. Results of bed-center, dip-parallel scanline surveys demonstrate Available online 8 January 2017 nearly identical fracture strikes and slight variation in dip between mudrock, chalk, and limestone beds. Fracture spacing tends to increase proportional to bed thickness in limestone and chalk beds; however, Keywords: Mechanical stratigraphy dramatic differences in fracture spacing are observed in mudrock. A direct relationship is observed be- Natural fractures tween fracture spacing/thickness ratio and rock competence. Vertical fracture penetrations measured Fracture spacing from the middle of chalk and limestone beds generally extend to and often beyond bed boundaries into Fracture penetration the vertically adjacent mudrock beds. -

How Do Sedimentary Beds Form? – and Why Can We See Them? Demonstrating How the Beds in Sedimentary Rocks Are Deposited

Earthlearningidea – https://www.earthlearningidea.com How do sedimentary beds form? – and why can we see them? Demonstrating how the beds in sedimentary rocks are deposited Sedimentary rock layers are called beds, if they are more than 1 cm thick*. Each bed was laid down by a single sedimentary event, so the beds in the photo below were laid down by many, many separate events of sand deposition. The junction between beds is called a bedding plane and is normally a flat horizontal surface. Bedding in a measuring cylinder, with sands of different colour on the left and sands of one colour (but added in several sedimentary episodes or spoonfuls) on the right. (Chris King). So, later when the sands have been compacted and cemented to form sandstones, the slight Bedding in 140 million year old sedimentary rocks, Morro differences between the top of one bed and the Solar, Lima, Peru. This series of beds has been tilted by bottom of another remain. These are later tectonic forces. attacked by weathering and erosion so that the Image licensed by Miguel Vera León under the Creative bedding plane and the beds can be seen. Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Bedding planes are even clearer if there was an You can make your own beds by filling a 2 interval of time between the laying down of the measuring cylinder /3 full of water and adding upper and lower beds. In that time interval, the spoonfuls of sand. Each spoonful you add is a lower bed may have become more compacted, or single sedimentary episode and the junction partially eroded or sedimentary structures like between each layer is a bedding plane. -

B-127 Lithostratigraphic Framework Of

&A 'NlOO,G-3 &i flo, 12 7 g l F£i&f THE LITHOSTRATIGRAPHIC FRAMEWORK OF \;\ .-t "- THE UPPERMOST CRETACEOUS AND LOWER TERTIARY OF EASTERN BURKE COUNTY, GEORGIA Paul F. Huddlestun and Joseph H. Summerour Work Performed in Cooperation with United States Geological Survey (Cooperative Agreement Number 1434-92-A-0959) and U. S. Department of Energy (Cooperative Agreement Number DE-FG-09-92SR12868) GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION GEORGIA GEOLOGIC SURVEY Atlanta 1996 Bulletin 127 THE LITHOSTRATIGRAPHIC FRAMEWORK OF THE UPPERMOST CRETACEOUS AND LOWER TERTIARY OF EASTERN BURKE COUNTY, GEORGIA Paul F. Huddlestun and Joseph H. Summerour GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Lonice C. Barrett, Commissioner ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Harold F. Reheis, Director GEORGIA GEOLOGIC SURVEY William H. McLemore, State Geologist Atlanta 1996 Bulletin 127 ABSTRACT One new formation, two new members, and a redefinition of an established lithostratigraphic unit are formally introduced here. The Oconee Group is formally recognized in the Savannah River area and four South Carolina Formations not previously used in Georgia by the Georgia Geologic Survey are recognized in eastern Burke County. The Still Branch Sand is a new formation and the two new members are the Bennock Millpond Sand Member of the Still Branch Sand and the Blue Bluff Member of the Lisbon Formation. The four South Carolina formations recognized in eastern Burke CountY include the Steel Creek Formation and Snapp Formation of the Oconee Group, the Black Mingo Formation (undifferentiated), and the Congaree Formation. The Congaree Formation and Still Branch Sand are considered to be lithostratigraphic components of the Claiborne Group. -

GY 111 Lecture Notes Bed Attitude (AKA – Strike and Dip)

GY 111 Lecture Notes D. Haywick (2008-09) 1 GY 111 Lecture Notes Bed Attitude (AKA – Strike and Dip) Lecture Goals: A) Beds in 3D space; the problem of orientation B) Strike and Dip C) Geological maps 1: horizontal and inclined bedding on map* Reference: Press et al., 2004, Chapter 11; Grotzinger et al., 2007, Chapter 7; p 152-154 GY 111 Lab manual Chapter 5 A) Beds in 3D space; the problem of orientation Up until now, I have been illustrating just about every important geological concept in two dimensions. For example, in the last lecture, I illustrated the Principle of Superposition with the adjacent cartoon: The thing is that beds are planes not lines and therefore, I really should have used a three dimensional or perspective cartoon to illustrate superposition. This one is more realistic, albeit a bit more annoying to draw on the fly during a lecture: GY 111 Lecture Notes D. Haywick (2008-09) 2 If you think about it, it is relatively easy to describe the orientation of horizontal bedding. All you have to say is "horizontal" and everyone immediately visualizes a flat surface ( e.g., a table, the floor, etc.). But we have a serious problem when it comes to describing the orientation of an inclined bed. Picture a tilted plane like the one drawn in the next cartoon. Were you to just say that the bed is inclined, every insightful person that you met (e.g., your fellow GY 111 classmates) would ask, "how much and in which direction?" After all, each of the beds in the next cartoon is inclined, but every one is inclined differently. -

1 PATTERNS of MONTOYA GROUP DEPOSITION, DIAGENESIS, and RESERVOIR DEVELOPMENT in the PERMIAN BASIN Rebecca H. Jones ABSTRACT

PATTERNS OF MONTOYA GROUP DEPOSITION, DIAGENESIS, AND RESERVOIR DEVELOPMENT IN THE PERMIAN BASIN Rebecca H. Jones ABSTRACT Rocks composing both the Montoya (Upper Ordovician) and Fusselman (Lower Silurian) Formations were deposited during the global climate transition from greenhouse conditions to unusually short-lived icehouse conditions on a broad, shallow-water platform. The Montoya and the Fusselman also share many reservoir characteristics and have historically been grouped together in terms of production and plays. Recently, however, the Montoya has garnered attention on its own, with new gas production in the Permian Basin and increased interest in global Ordovician climate. Recent outcrop work has yielded new lithologic and biostratigraphic constraints and an interpretation of four third-order Montoya sequences within Sloss’s second-order Tippecanoe I sequence. The Montoya Group comprises the Upham, Aleman, and Cutter Formations, from oldest to youngest. The Upham contains a basal, irregularly present sandstone member called the Cable Canyon. The boundary between the Montoya and the Fusselman is readily definable where a thin shale called the Sylvan is present but can be difficult to discern where the Sylvan is absent. Montoya rocks were deposited from the latest Chatfieldian to the end of the Richmondian stage of the late Mohawkian and Cincinnatian series (North American) of the Upper Ordovician. Montoya reservoir quality is generally better in the northern part of the Permian Basin where it is primarily dolomite compared to limestone Montoya reservoirs in the south. Reservoir quality is also better in the lower part of the unit compared to the upper, owing to a predominance of porous and permeable subtidal ooid grainstones and skeletal packstones in the former and peritidal facies in the latter. -

SW Science 10 Unit 6 Relative Dating Worksheet

SW Science 10 Unit 6 Relative Dating Worksheet Name: __________________________________ Student #: ____________ 6.2 Geologic Time 6.2.2 Relative Dating The Law of Superposition In any undisturbed sequence of strata, the oldest layer is at the bottom of the sequence, and the youngest layer is at the top of the sequence. The Cross-Cutting Law Any feature that cuts across a body of sediment or rock is younger than the body of sediment or rock that it cuts across. NOTE: • A fracture is a crack in rock. • A fault is a fracture along which movement has occurred. The Law of Inclusions If one rock body contains fragments of another rock body it must be younger than the fragments of rock it contains. OR…The inclusions are older than the rocks which contain them. Inclusions Inclusions of B are older than C. Page 2 Telling Relative Time Use the laws of superposition, inclusions and cross-cutting relationships to determine the relative ages of the following cross-sections. Determine the OLDEST bed FIRST. 1 2 3 SW SC10 UNIT 6 Earth Forces Relative Dating WS Page 3 H G F E C D B A 4 M 5 Outline the sequence of events in the cross sections below by numbering each rock unit or event in the order in which it occurred or was deposited. Youngest ________ ________ ________ ________ 6 Oldest ________ E SW SC10 UNIT 6 Earth Forces Relative Dating WS Page 4 C Refer to the cross-section on the left. For each of the following pairs of rock layers, identify the relative dating law that would be used to determine which bed was older and which was younger. -

Primary Sedimentary Structures in Some Metamorphic Rocks

Sedimentary Structures in Metamorphic Rocks Maine Geological Survey Maine Geologic Facts and Localities November, 2006 Primary Sedimentary Structures in Some Metamorphic Rocks Text by Thomas K. Weddle Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 1 Sedimentary Structures in Metamorphic Rocks Maine Geological Survey Introduction In most introductory geology classes, be it in an elementary school or at a college, students learn that there are three fundamental rock types: sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic rocks. Sedimentary rocks are formed by the deposition of sediment by several processes, either by settling of sediment particles in a body of water, by chemical precipitation in water, or by transportation of the particles by water such as streams and rivers, or by wind (Figures 1-3). Maine Geological Survey Photo by Thomas K. Weddle K. Thomas by Photo Figure 1. Glacial marine sand beds with nearly parallel, horizontal layering, Buckfield, ME (entrenching tool for scale). Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 2 Sedimentary Structures in Metamorphic Rocks Maine Geological Survey Sedimentary Rocks Maine Geological Survey Photo by Thomas K. Weddle K. Thomas by Photo Figure 2. Fluvial trough cross bedding in slightly gravelly, coarse sand. The cross bed sets are incised into one another and highlighted by the darker colored layers (entrenching tool for scale), Buckfield, Maine. Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 3 Sedimentary Structures in Metamorphic Rocks Maine Geological Survey Sedimentary Rocks Maine Geological Survey Photo by Thomas K. Weddle K. Thomas by Photo Figure 3. Coarse cobble gravel in a glacial fluvial deposit, Kingfield, Maine (entrenching tool for scale). -

Lithostratigraphic Units

INTEGRATED STRATIGRAPHY Amalia Spina Amalia Spina, PhD. Office: Palazzina di Geologia, Second floor Tel. 0755852696 E-mail: [email protected] - Principles of stratigraphy - The time in stratigraphy; geological chronology (relative and absolute) the temporal sequence of events; standard global chronostratigraphical scale. Comparison between the stratigraphic scales in marine and continental successions. - Stratigraphic units standard (definition and principle): law of superimposition, principle of original horizontality, of lateral continuity and of biotic succession, the Stratigraphic Code. - The sedimentary cyclicity - Lithostratigraphy - Magnetostratigraphy - Biostratigraphy - Chemostratigraphy - Cronostratigraphy and geochronology - Astronomic cyclostratigraphy - Sequence stratigraphy - Palaeogeographic reconstructions. Prerequisites: In order to better comprehend the main topics of integrated stratigraphy, the students that follow this course must have: - knowledge of the fundamentals of geology; - knowledge of the sedimentary rocks (classification); - knowledge of the principle of stratigraphy; - knowledge of the principle of palaeontology; - knowledge of the principle of sedimentology; These preconditions are important for attending and not attending students. Written test: it consist of the solution of multiple choice test and graphic /practical exercises. The number of questions ranges between 15 and 30 on the basis of the difficulty.The test has a duration of no more than 80 minutes. The goal of the test is to verify the knowledge acquired on the course contents in order to ensure that the student learned the principles of integrated stratigraphy and its main applications. To complete the evaluation the test also consists on the discussion of a case study proposed by the Professor carried out individually or in small groups (max three students).It consists to discuss the stratigraphic features of a certain geological area and the implications for the subsurface hydrocarbon exploitation. -

The Old Red Sandstone of Britain and Ireland – a Review

The Old Red Sandstone of Britain and Ireland – a review RS Kendall British Geological Survey - Cardiff University, Main Building, Park Place, Cardiff. CF10 3AT. [email protected] Abstract The Old Red Sandstone (ORS) is an informal term which is given to continental, predominantly siliclastic, strata of late Silurian to early Carboniferous age which were deposited across the continent of Laurussia at sub-tropic to tropical latitudes. The coincidental development of land plants had a major impact on the atmosphere and global climate by lowering atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, which profoundly affected the style of alluvial sedimentation during this interval, by stabilising flood plains and facilitating the development of soils. The ORS also provides examples of syn- to post- orogenic deposition related to the Caledonian Orogeny, which was affected by synchronous tectonism and volcanism. The influence of Variscan tectonics on basin deformation and tectonism are also evident in the ORS sequence. In October 2014, a symposium was held, organised by the South Wales Geologists’ Association, entitled The Old Red Sandstone: is it Old, is it Red and is it all Sandstone? The event consisted of talks and posters on topics associated with the Old Red Sandstone deposits, principally of Wales and the Welsh Borders and the Scottish Borders in the UK, and included a series of field trips. Seven of the speakers have contributed manuscripts which are presented in this volume. These include papers discussing fossil fish and plant assemblages, the Fforest Fawr Geopark, Old Red Sandstone building stones, and soft sediment deformation. A brief report on the event and acknowledgements is also included. -

48. Laboratory-Determined Sound Velocity

48. LABORATORY-DETERMINED SOUND VELOCITY, POROSITY, WET-BULK DENSITY, ACOUSTIC IMPEDANCE, ACOUSTIC ANISOTROPY, AND REFLECTION COEFFICIENTS FOR CRETACEOUS-JURASSIC TURBIDITE SEQUENCES AT DEEP SEA DRILLING PROJECT SITES 370 AND 416 OFF THE COAST OF MOROCCO1 Robert E. Boyce, Deep Sea Drilling Project, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California ABSTRACT From 661 to 880 m beneath the seafloor at DSDP Sites 370 and 416 are Albian to Barremian claystone with some limestone, sandstone, and siltstone. Compressional-wave velocities ranged from 1.70 to 4.37 km/s, with an average in situ vertical velocity of 1.93 km/s. From 880 to 1430 m are Hauterivian to Valanginian turbidites of alternating graded calcareous and quartzose cycles from siltstone or fine sandstone to mudstone. Compressional-wave velocities range from 1.80 to 4.96 km/s with an average in situ velocity of 2.61 km/s. From 1430 to 1624 m are early Valanginian to Tithonian (Kimmeridgian?) turbidites, with alternating quartzose silt- stone grading to mudstone cycles with hard micritic limestone and calcarenite (calciturbidites). Compressional-wave velocities range from 2.26 to 5.7 km/s, with an average in situ vertical velocity of 3.25 km/s. Acoustic anisotropy is 0 to 30% faster parallel to bedding in Cretaceous to Tithonian sandstone-siltstone turbidites in mudstone and minor limestone from 661 to 1624 m below the seafloor. Between 2.0(?) km/s and 4.2(?) km/s, anisot- ropy becomes particularly significant (below 1178 m), where the anisotropy is about +0.4 km/s or greater. The mud- stone, softer sandstone, and softer siltstone tend to have velocities around 2.0 to 2.5 km/s; the cemented sandstone and limestone cluster around 2.5 km/s to 4.2 km/s; thus the relative percentage anisotropy is greater for lower-velocity li- thologies. -

1 Structural Geology

Structural Geology – Laboratory 9 _____________________ (Name) Geologic maps show the distribution of different types of structures and rock stratigraphic units generally on a topographic base such as a quadrangle map. Key structures that are commonly shown include (1) bedding attitudes, (2) anticlines, (3) synclines, and (4) faults. A bedding attitude is defined as the strike and dip of a bed. Strike is the direction of a line produced by the intersection of an imaginary horizontal plane with an inclined bed. From previous laboratories you should know that based on the Principle of Original Horizontality sedimentary beds are originally deposited as a series of horizontal layers one on top of another. Such beds would have an infinite number of strike lines as the intersection of an imaginary horizontal plane with a horizontal bed is an infinite number of lines oriented from 0o to 360o (Figure 1). 1 In contrast, if a bed is inclined relative to the horizontal, then its intersection with an imaginary horizontal plane produces one and only one line (Figure 2). The direction of this line is the strike of the bed. 2 Dip is the angle between the imaginary horizontal plane and the inclined bed measured in a plane oriented at 90o to the strike line (Figure 3). In all of the above illustrations strike and dip is defined for an inclined layer such as a bed or lamination or rock stratigraphic unit (e.g., a member or formation). However, the orientation of any planar surface can be expressed by its strike and dip. For example, the orientation of a fault or foliation surface is commonly given as its strike and dip. -

Depositional Environments

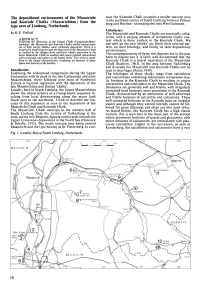

trast the Kunrade Chalk occupies a smaller area The depositional environments of the Maastricht outcrop in the northeast corner of South Limburg between Valken- and Kunrade Chalks (Maastrichtian) from the burg and Heerlen - extending also into West Germany. type area of Limburg, Netherlands Lithofacies: R.E. Pollock by The Maastricht and Kunrade Chalks are essentially calca- of reous, with a varying amount terrigenous clastic con- ABSTRACT: tent which is more evident in the Kunrade Chalk. We Following the deposition of the Gulpen Chalk ICampanian-Maas- the two ‘chalks’ their trichlianl. the Maastricht and Kunrade Chalks exhibit typicalfeate- can split up on, firstly outcrop pat- shallow carbonate There and their res of high energy water deposition. is a tern, on their lithology, finally on depositional progressive shallowing through the depositionof the Maastricht Chalk environments. as typifiedby the changes from calcilutite Ichalk I deposition in the The contemporaneity of these two deposits has in the past lower Maastricht Chalk to medium and coarse grained calcarenities been in but it is fairly well documented that the with occasional calcirudites in the higher levels. This trend is paral- dispute Kunrade Chalk is lateral the leled in the faunal characteristics, exhibiting an increase in abun- a equivalent of Maastricht dance and diversity of the benthos. Chalk In the between (Romein, 1963). area Valkenburg and Kunrade the Maastricht and Kunrade Chalks can be Introduction: seen to interfinger (Kruit, 1949). the Following widespread trangression during the Upper The of these chalks from calcisiltites lithologies range with its in the late and Cretaceous peak Campanian early and calcarenites containing subordinate terrigenous clas- Maastrichtian, there followed over most of Northwest tic horizons in the Kunrade Chalk to medium to coarse with the of the Europe a regional regression deposition calcarenites and calcirudites in the Maastricht Chalk.