Practical Perl Tools: Scratch the Webapp Itch With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0019847 A1 Osmak (43) Pub

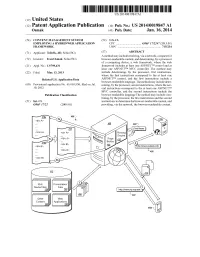

US 20140019847A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0019847 A1 OSmak (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 16, 2014 (54) CONTENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM (52) U.S. Cl. EMPLOYINGA HYBRD WEB APPLICATION CPC .................................. G06F 17/2247 (2013.01) FRAMEWORK USPC .......................................................... 71.5/234 (71) Applicant: Telerik, AD, Sofia (BG) (57) ABSTRACT A method may include receiving, via a network, a request for (72) Inventor: Ivan Osmak, Sofia (BG) browser-renderable content, and determining, by a processor of a computing device, a web framework, where the web (21) Appl. No.: 13/799,431 framework includes at least one ASP.NETTM control and at least one ASP.NETTM MVC controller. The method may (22) Filed: Mar 13, 2013 include determining, by the processor, first instructions, where the first instructions correspond to the at least one Related U.S. Application Data ASP.NETTM control, and the first instructions include a browser-renderable language. The method may include deter (60) Provisional application No. 61/669,930, filed on Jul. mining, by the processor, second instructions, where the sec 10, 2012. ond instructions correspond to the at least one ASP.NETTM MVC controller, and the second instructions include the Publication Classification browser-renderable language The method may include com bining, by the processor, the first instructions and the second (51) Int. Cl. instructions to determine the browser-renderable content, and G06F 7/22 (2006.01) providing, via the network, the browser-renderable content. Routing Engine Ric Presentation Media Fies : Fies 22 Applications 28 Patent Application Publication Jan. 16, 2014 Sheet 1 of 8 US 2014/001.9847 A1 Patent Application Publication Jan. -

Web Development and Perl 6 Talk

Click to add Title 1 “Even though I am in the thralls of Perl 6, I still do all my web development in Perl 5 because the ecology of modules is so mature.” http://blogs.perl.org/users/ken_youens-clark/2016/10/web-development-with-perl-5.html Web development and Perl 6 Bailador BreakDancer Crust Web Web::App::Ballet Web::App::MVC Web::RF Bailador Nov 2016 BreakDancer Mar 2014 Crust Jan 2016 Web May 2016 Web::App::Ballet Jun 2015 Web::App::MVC Mar 2013 Web::RF Nov 2015 “Even though I am in the thralls of Perl 6, I still do all my web development in Perl 5 because the ecology of modules is so mature.” http://blogs.perl.org/users/ken_youens-clark/2016/10/web-development-with-perl-5.html Crust Web Bailador to the rescue Bailador config my %settings; multi sub setting(Str $name) { %settings{$name} } multi sub setting(Pair $pair) { %settings{$pair.key} = $pair.value } setting 'database' => $*TMPDIR.child('dancr.db'); # webscale authentication method setting 'username' => 'admin'; setting 'password' => 'password'; setting 'layout' => 'main'; Bailador DB sub connect_db() { my $dbh = DBIish.connect( 'SQLite', :database(setting('database').Str) ); return $dbh; } sub init_db() { my $db = connect_db; my $schema = slurp 'schema.sql'; $db.do($schema); } Bailador handler get '/' => { my $db = connect_db(); my $sth = $db.prepare( 'select id, title, text from entries order by id desc' ); $sth.execute; layout template 'show_entries.tt', { msg => get_flash(), add_entry_url => uri_for('/add'), entries => $sth.allrows(:array-of-hash) .map({$_<id> => $_}).hash, -

Algorithmic Reflections on Choreography

ISSN: 1795-6889 www.humantechnology.jyu.fi Volume 12(2), November 2016, 252–288 ALGORITHMIC REFLECTIONS ON CHOREOGRAPHY Pablo Ventura Daniel Bisig Ventura Dance Company Zurich University of the Arts Switzerland Switzerland Abstract: In 1996, Pablo Ventura turned his attention to the choreography software Life Forms to find out whether the then-revolutionary new tool could lead to new possibilities of expression in contemporary dance. During the next 2 decades, he devised choreographic techniques and custom software to create dance works that highlight the operational logic of computers, accompanied by computer-generated dance and media elements. This article provides a firsthand account of how Ventura’s engagement with algorithmic concepts guided and transformed his choreographic practice. The text describes the methods that were developed to create computer-aided dance choreographies. Furthermore, the text illustrates how choreography techniques can be applied to correlate formal and aesthetic aspects of movement, music, and video. Finally, the text emphasizes how Ventura’s interest in the wider conceptual context has led him to explore with choreographic means fundamental issues concerning the characteristics of humans and machines and their increasingly profound interdependencies. Keywords: computer-aided choreography, breaking of aesthetic and bodily habits, human– machine relationships, computer-generated and interactive media. © 2016 Pablo Ventura & Daniel Bisig, and the Agora Center, University of Jyväskylä DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.201611174656 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. 252 Algorithmic Reflections on Choreography INTRODUCTION The purpose of this article is to provide a first-hand account of how a thorough artistic engagement with functional and conceptual aspects of software can guide and transform choreographic practice. -

Final CATALYST Framework Architecture

D2.3 F in al CATALYST Framework Architect ure WORKPACKAGE PROGRAMME IDENTIFIER WP2 H2020-EE-2016-2017 DOCUMENT PROJECT NUMBER D2.3 768739 VERSION START DATE OF THE PROJECT 1.0 01/10/2017 PUBLISH DATE DURATION 03/06/2019 36 months DOCUMENT REFERENCE CATALYST.D2.3.PARTNER.WP2.v1.0 PROGRAMME NAME ENERGY EFFICIENCY CALL 2016-2017 PROGRAMME IDENTIFIER H2020-EE-2016-2017 TOPIC Bringing to market more energy efficient and integrated data centres TOPIC IDENTIFIER EE-20-2017 TYPE OF ACTION IA Innovation action PROJECT NUMBER 768739 PROJECT TITLE CATALYST COORDINATOR ENGINEERING INGEGNERIA INFORMATICA S.p.A. (ENG) PRINCIPAL CONTRACTORS SINGULARLOGIC ANONYMI ETAIREIA PLIROFORIAKON SYSTIMATON KAI EFARMOGON PLIROFORIKIS (SiLO), ENEL.SI S.r.l (ENEL), ALLIANDER NV (ALD), STICHTING GREEN IT CONSORTIUM REGIO AMSTERDAM (GIT), SCHUBERG PHILIS BV (SBP), QARNOT COMPUTING (QRN), POWER OPERATIONS LIMITED (POPs), INSTYTUT CHEMII BIOORGANICZNEJ POLSKIEJ AKADEMII NAUK (PSNC), UNIVERSITATEA TEHNICA CLUJ-NAPOCA (TUC) DOCUMENT REFERENCE CATALYST.D2.3.PARTNER.WP2.v1.0 WORKPACKAGE: WP2 DELIVERABLE TYPE R (report) AVAILABILITY PU (Public) DELIVERABLE STATE Final CONTRACTUAL DATE OF DELIVERY 31/05/2019 ACTUAL DATE OF DELIVERY 03/06/2019 DOCUMENT TITLE Final CATALYST Framework Architecture AUTHOR(S) Marzia Mammina (ENG), Terpsi Velivassaki (SiLO), Tudor Cioara (TUC), Nicolas Sainthérant (QRN), Artemis Voulkidis (POPs), John Booth (GIT) REVIEWER(S) Artemis Voulkidis (POPs) Terpsi Velivassaki (SILO) SUMMARY (See the Executive Summary) HISTORY (See the Change History Table) -

Development of a Novel Combined Catalyst and Sorbent for Hydrocarbon Reforming Justinus A

Chemical and Biological Engineering Publications Chemical and Biological Engineering 2005 Development of a novel combined catalyst and sorbent for hydrocarbon reforming Justinus A. Satrio Iowa State University Brent H. Shanks Iowa State University, [email protected] Thomas D. Wheelock Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cbe_pubs Part of the Chemical Engineering Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ cbe_pubs/220. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemical and Biological Engineering at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chemical and Biological Engineering Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Development of a novel combined catalyst and sorbent for hydrocarbon reforming Abstract A combined catalyst and sorbent was prepared and utilized for steam reforming methane and propane in laboratory-scale systems. The am terial was prepared in the form of small spherical pellets having a layered structure such that each pellet consisted of a highly reactive lime or dolime core enclosed within a porous but strong protective shell made of alumina in which a nickel catalyst was loaded. The am terial served two functions by catalyzing the reaction of hydrocarbons with steam to produce hydrogen while simultaneously absorbing carbon dioxide formed by the reaction. The in situ er moval of CO 2 shifted the reaction equilibrium toward increased H 2 concentration and production. -

Bachelorarbeit

BACHELORARBEIT Realisierung von verzögerungsfreien Mehrbenutzer Webapplikationen auf Basis von HTML5 WebSockets Hochschule Harz University of Applied Sciences Wernigerode Fachbereich Automatisierung und Informatik im Fach Medieninformatik Erstprüfer: Prof. Jürgen K. Singer, Ph.D. Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Olaf Drögehorn Erstellt von: Lars Häuser Datum: 16.06.2011 Einleitung Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Zielsetzung ..................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Aufbau der Arbeit ........................................................................................... 6 2 Grundlagen .............................................................................................................. 8 2.1 TCP/IP ............................................................................................................ 8 2.2 HTTP .............................................................................................................. 9 2.3 Request-Response-Paradigma (HTTP-Request-Cycle) .............................. 10 2.4 Klassische Webanwendung: Synchrone Datenübertragung ....................... 11 2.5 Asynchrone Webapplikationen .................................................................... 11 2.6 HTML5 ......................................................................................................... 12 3 HTML5 WebSockets ............................................................................................. -

The Lift Approach

Science of Computer Programming 102 (2015) 1–19 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of Computer Programming www.elsevier.com/locate/scico Analyzing best practices on Web development frameworks: The lift approach ∗ María del Pilar Salas-Zárate a, Giner Alor-Hernández b, , Rafael Valencia-García a, Lisbeth Rodríguez-Mazahua b, Alejandro Rodríguez-González c,e, José Luis López Cuadrado d a Departamento de Informática y Sistemas, Universidad de Murcia, Campus de Espinardo, 30100 Murcia, Spain b Division of Research and Postgraduate Studies, Instituto Tecnológico de Orizaba, Mexico c Bioinformatics at Centre for Plant Biotechnology and Genomics, Polytechnic University of Madrid, Spain d Computer Science Department, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain e Department of Engineering, School of Engineering, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Spain a r t i c l e i n f oa b s t r a c t Article history: Choosing the Web framework that best fits the requirements is not an easy task for Received 1 October 2013 developers. Several frameworks now exist to develop Web applications, such as Struts, Received in revised form 18 December 2014 JSF, Ruby on Rails, Grails, CakePHP, Django, and Catalyst. However, Lift is a relatively new Accepted 19 December 2014 framework that emerged in 2007 for the Scala programming language and which promises Available online 5 January 2015 a great number of advantages and additional features. Companies such as Siemens© and Keywords: IBM®, as well as social networks such as Twitter® and Foursquare®, have now begun to Best practices develop their applications by using Scala and Lift. Best practices are activities, technical Lift or important issues identified by users in a specific context, and which have rendered Scala excellent service and are expected to achieve similar results in similar situations. -

2Nd USENIX Conference on Web Application Development (Webapps ’11)

conference proceedings Proceedings of the 2nd USENIX Conference Application on Web Development 2nd USENIX Conference on Web Application Development (WebApps ’11) Portland, OR, USA Portland, OR, USA June 15–16, 2011 Sponsored by June 15–16, 2011 © 2011 by The USENIX Association All Rights Reserved This volume is published as a collective work. Rights to individual papers remain with the author or the author’s employer. Permission is granted for the noncommercial reproduction of the complete work for educational or research purposes. Permission is granted to print, primarily for one person’s exclusive use, a single copy of these Proceedings. USENIX acknowledges all trademarks herein. ISBN 978-931971-86-7 USENIX Association Proceedings of the 2nd USENIX Conference on Web Application Development June 15–16, 2011 Portland, OR, USA Conference Organizers Program Chair Armando Fox, University of California, Berkeley Program Committee Adam Barth, Google Inc. Abdur Chowdhury, Twitter Jon Howell, Microsoft Research Collin Jackson, Carnegie Mellon University Bobby Johnson, Facebook Emre Kıcıman, Microsoft Research Michael E. Maximilien, IBM Research Owen O’Malley, Yahoo! Research John Ousterhout, Stanford University Swami Sivasubramanian, Amazon Web Services Geoffrey M. Voelker, University of California, San Diego Nickolai Zeldovich, Massachusetts Institute of Technology The USENIX Association Staff WebApps ’11: 2nd USENIX Conference on Web Application Development June 15–16, 2011 Portland, OR, USA Message from the Program Chair . v Wednesday, June 15 10:30–Noon GuardRails: A Data-Centric Web Application Security Framework . 1 Jonathan Burket, Patrick Mutchler, Michael Weaver, Muzzammil Zaveri, and David Evans, University of Virginia PHP Aspis: Using Partial Taint Tracking to Protect Against Injection Attacks . -

James Reynolds What Is a Ruby on Rails Why Is It So Cool Major Rails Features Web Framework

Ruby On Rails James Reynolds What is a Ruby on Rails Why is it so cool Major Rails features Web framework Code and tools for web development A webapp skeleton Developers plug in their unique code Platforms Windows Mac OS X Linux Installation Mac OS X 10.5 will include Rails Mac OS X 10.4 includes Ruby Most people reinstall it anyway From scratch Drag and drop Locomotive Databases Mysql Oracle SQLite Firebird PostgreSQL SQL Server DB2 more Webservers Apache w/ FastCGI or Mongrel LightTPD WEBrick "IDE's" TextMate and Terminal (preferred) RadRails jEdit Komodo Arachno Ruby Has "inspired" Grails CakePHP Trails PHP on TRAX Sails MonoRail Catalyst TrimPath Junction Pylons WASP ColdFusion on Wheels And perhaps more... Why is it so cool? Using the right tool for the job y = x^2 vs y = x^0.5 Right tool Rails is the most well thought-out web development framework I've ever used. And that's in a decade of doing web applications for a living. I've built my own frameworks, helped develop the Servlet API, and have created more than a few web servers from scratch. Nobody has done it like this before. James Duncan Davidson, Creator of Tomcat and Ant y = x ^ 2 vs y = x ^ 0.5 Features Features Work Work Typical Rare y = x ^ 2 vs y = x ^ 0.5 Feature ceiling Features Features Work Work This is a no-brainer... Ruby on Rails is a breakthrough in lowering the barriers of entry to programming. Powerful web applications that formerly might have taken weeks or months to develop can be produced in a matter of days. -

Two Important Problems on Quantum Coherence

Two Important Problems on Quantum Coherence Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of B. Tech and Master of Science by Research in Computer Science and Engineering by Udit Kamal Sharma 201202094 [email protected] Center for Security, Theory and Algorithmic Research (CSTAR) International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad - 500 032, INDIA December 2017 Copyright © Udit Kamal Sharma, 2017 All Rights Reserved International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad, India CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORSHIP I, Udit Kamal Sharma, declare that the thesis, titled “Two Important Problems on Quantum Coher- ence”, and the work presented herein are my own. I confirm that this work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for a research degree at IIIT-Hyderabad. Date Signature of the Candidate International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad, India CERTIFICATE It is certified that the work contained in this thesis, titled “Two Important Problems on Quantum Coherence ” by Udit Kamal Sharma, has been carried out under my supervision and is not submitted elsewhere for a degree. Date Adviser: Dr. Indranil Chakrabarty Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Indranil Chakrabarty, for his immense guidance, patience and helpful suggestions, without which, my journey in the uncharted waters of research would have been impossible. I would like to thank him for first introducing me to this field of quantum information theory and motivating me thereafter to pursue research in this direction. I would like to thank all the faculty and non-teaching staff at CSTAR for providing me an excellent convivial environment to pursue my research. -

Pragmaticperl-Interviews-A4.Pdf

Pragmatic Perl Interviews pragmaticperl.com 2013—2015 Editor and interviewer: Viacheslav Tykhanovskyi Covers: Marko Ivanyk Revision: 2018-03-02 11:22 © Pragmatic Perl Contents 1 Preface .......................................... 1 2 Alexis Sukrieh (April 2013) ............................... 2 3 Sawyer X (May 2013) .................................. 10 4 Stevan Little (September 2013) ............................. 17 5 chromatic (October 2013) ................................ 22 6 Marc Lehmann (November 2013) ............................ 29 7 Tokuhiro Matsuno (January 2014) ........................... 46 8 Randal Schwartz (February 2014) ........................... 53 9 Christian Walde (May 2014) .............................. 56 10 Florian Ragwitz (rafl) (June 2014) ........................... 62 11 Curtis “Ovid” Poe (September 2014) .......................... 70 12 Leon Timmermans (October 2014) ........................... 77 13 Olaf Alders (December 2014) .............................. 81 14 Ricardo Signes (January 2015) ............................. 87 15 Neil Bowers (February 2015) .............................. 94 16 Renée Bäcker (June 2015) ................................ 102 17 David Golden (July 2015) ................................ 109 18 Philippe Bruhat (Book) (August 2015) . 115 19 Author .......................................... 123 i Preface 1 Preface Hello there! You have downloaded a compilation of interviews done with Perl pro- grammers in Pragmatic Perl journal from 2013 to 2015. Since the journal itself is in Russian -

What Is Perl

AdvancedAdvanced PerlPerl TechniquesTechniques DayDay 22 Dave Cross Magnum Solutions Ltd [email protected] Schedule 09:45 – Begin 11:15 – Coffee break (15 mins) 13:00 – Lunch (60 mins) 14:00 – Begin 15:30 – Coffee break (15 mins) 17:00 – End FlossUK 24th February 2012 Resources Slides available on-line − http://mag-sol.com/train/public/2012-02/ukuug Also see Slideshare − http://www.slideshare.net/davorg/slideshows Get Satisfaction − http://getsatisfaction.com/magnum FlossUK 24th February 2012 What We Will Cover Modern Core Perl − What's new in Perl 5.10, 5.12 & 5.14 Advanced Testing Database access with DBIx::Class Handling Exceptions FlossUK 24th February 2012 What We Will Cover Profiling and Benchmarking Object oriented programming with Moose MVC Frameworks − Catalyst PSGI and Plack FlossUK 24th February 2012 BenchmarkingBenchmarking && ProfilingProfiling Benchmarking Ensure that your program is fast enough But how fast is fast enough? premature optimization is the root of all evil − Donald Knuth − paraphrasing Tony Hoare Don't optimise until you know what to optimise FlossUK 24th February 2012 Benchmark.pm Standard Perl module for benchmarking Simple usage use Benchmark; my %methods = ( method1 => sub { ... }, method2 => sub { ... }, ); timethese(10_000, \%methods); Times 10,000 iterations of each method FlossUK 24th February 2012 Benchmark.pm Output Benchmark: timing 10000 iterations of method1, method2... method1: 6 wallclock secs \ ( 2.12 usr + 3.47 sys = 5.59 CPU) \ @ 1788.91/s (n=10000) method2: 3 wallclock secs \ ( 0.85 usr + 1.70 sys = 2.55 CPU) \ @ 3921.57/s (n=10000) FlossUK 24th February 2012 Timed Benchmarks Passing timethese a positive number runs each piece of code a certain number of times Passing timethese a negative number runs each piece of code for a certain number of seconds FlossUK 24th February 2012 Timed Benchmarks use Benchmark; my %methods = ( method1 => sub { ..