A Demographic Documenation of ISIS's Attack on the Yazidi Village Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Her Shoulders

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE ON HER SHOULDERS Lead Sponsor Exclusive Education Partner Supported by An agency of the Government of Ontario Un organisme du gouvernement de l’Ontario Additional support is provided by The Andy and Beth Burgess Family Foundation, the Hal Jackman Foundation, J.P. Bickell Foundation and through contributions by Like us on Facebook.com/docsforschools individual donors. WWW.HOTDOCS.CA/YOUTH HEADER ON HER SHOULDERS Directed by Alexandria Bombach 2018 | USA | 94 min In English, Kurmanji and Arabic, with English subtitles TEACHER’S GUIDE This guide has been designed to help teachers and students enrich their experience of On Her Shoulders by providing support in the form of questions and activities. There are a range of questions that will help teachers frame discussions with their class, activities for before, during and after viewing the film, and some weblinks that provide starting points for further research or discussion. The Film The Filmmaker Having seen and experienced the atrocities committed Alexandria Bombach is an award-winning cinematographer, against the Yazidi community in Iraq, Nadia Murad becomes editor and director from Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her feature- the reluctant but powerful voice of her people in a crusade to length documentary On Her Shoulders follows Nadia Murad, get the world to finally pay attention to the genocide taking a 23-year-old Yazidi woman who survived genocide and place. The 23-year-old survived repeated sexual assaults and sexual slavery committed by ISIS. In addition to her feature bore witness to the ruthless murders of her loved ones. Now, documentary work, Alexandria’s production company Red her bravery to speak openly is put to the test daily as Reel has been producing award-winning, character-driven reporters, politicians and activists push for her to recount stories since 2009. -

The Mandaeans

The Mandaeans A Story of Survival in the Modern World PHOTO: DAVID MAURICE SMITH / OCULI refugees and spoken to immigration officials in Aus- The Mandaeans appear to be one of the most tralian embassies and international NGOs about their misunderstood and vulnerable groups. Apart from being desperate plight. She laments that the conditions in a small community, even fewer than Yazidis, they do which they live are far worse than she could have ever not belong to a large religious organisation or have imagined, and she fears they may have been forgotten links with powerful tribes that can protect them, so by the international community overwhelmed by the their vulnerability makes them an easy target. To make massive displacement and the humanitarian disaster matters worse they are scattered all over the country, caused by the Syrian civil war. so they are the only minority group in Iraq without a There is no doubt that more of a decade of sectarian safe enclave. If the violence persists, it is feared their infighting has had a devastating impact on Iraqi society ancient culture and religion will be lost forever. as a whole. But religious minority groups have borne the brunt of the violence. For the past 14 years Mand- andaeans have a long history of per- aeans, like many other minorities, have been subjected secution. Their survival into the modern to persecution, murder, kidnappings, displacement, world is little short of a miracle. Their forced conversion to Islam, forced marriage, cruel M origins can be traced to the Jordan treatment, confiscation of assets including property and Valley area and it is thought that they may have migrated the destruction of their cultural and religious heritage. -

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi Idps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi IDPs in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq May 20191 Contents 1) Access to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KR-I) ................................................................... 2 2) Humanitarian / Socio-Economic Situation in the KR-I ..................................................... 2 a) Shelter ........................................................................................................................................ 3 b) Employment .............................................................................................................................. 4 c) Education ................................................................................................................................... 6 d) Mental Health ............................................................................................................................ 8 e) Humanitarian Assistance ...................................................................................................... 10 3) Returns to Sinjar District........................................................................................................ 10 In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS) seized the districts of Sinjar, Tel Afar and the Ninewa Plains, leading to a mass exodus of Yazidis, Christians and other religious communities from these areas. Soon, reports began to surface regarding war crimes and serious human rights violations perpetrated by ISIS and associated armed groups. These included the systematic -

Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications the Hyper-Style and the Double Dedications

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 28 | 2015 Varia Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications The Hyper-style and the Double Dedications Eleni Fassa Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2333 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2333 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2015 Number of pages: 133-153 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Eleni Fassa, « Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications », Kernos [Online], 28 | 2015, Online since 01 October 2017, connection on 21 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ kernos/2333 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2333 This text was automatically generated on 21 December 2020. Kernos Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications 1 Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications The Hyper-style and the Double Dedications Eleni Fassa An extended version of this paper forms part of my PhD dissertation, cited here as FASSA (2011). My warmest thanks to Sophia Aneziri for her always insightful comments. This paper has benefited much from the constructive criticism of the anonymous referees of Kernos. 1 In Ptolemaic Egypt, two types of private dedications evolved, relating rulers, subjects and gods, most frequently, Sarapis and Isis.1 They were formed in two ways: the offering was made either to Sarapis and Isis (dative) for the Ptolemaic kings (ὑπέρ +genitive) — hereafter, these will be called the hyper-formula dedications2 — or to Sarapis, Isis (dative) and the Ptolemaic kings (dative), the so-called ‘double dedications’. -

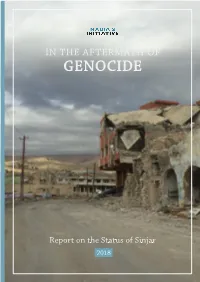

In the Aftermath of Genocide

IN THE AFTERMATH OF GENOCIDE Report on the Status of Sinjar 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS expertise, foremost the Yazidi families who participated in this work, but also a number of other vital contributors: ADVISORY BOARD Nadia Murad, Founder of Nadia’s Initiative Kerry Propper, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Elizabeth Schaeffer Brown, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Abid Shamdeen, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Numerous NGOs, U.N. agencies, and humanitarian aid professionals in Iraq and Kurdistan also provided guidance and feedback for this report. REPORT TEAM Amber Webb, lead researcher/principle author Melanie Baker, data and analytics Kenglin Lai, data and analytics Sulaiman Jameel, survey enumerator co-lead Faris Mishko, survey enumerator co-lead Special thanks to the team at Yazda for assisting with the coordination of this report. L AYOUT AND DESIGN Jens Robert Janke | www.jensrobertjanke.com PHOTOGRAPHY Amber Webb, Jens Robert Janke, and the Yazda Documentation Team. Images should not be reproduced without authorization. reflect those of Nadia’s Initiative. To protect the identities of those who participated in the research, all names have been changed and specific locations withheld. For more information please visit www.nadiasinitiative.org. © FOREWORD n August 3rd, 2014 the world endured yet another genocide. In the hours just before sunrise, my village and many others in the region of Sinjar, O Iraq came under attack by the Islamic State. Tat morning, IS militants began a campaign of ethnic cleansing to eradicate Yazidis from existence. In mere hours, many friends and family members perished before my eyes. Te rest of us, unable to flee, were taken as prisoners and endured unspeakable acts of violence. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Protecting Yazidi Cultural Heritage Through Women: an International Feminist Law Analysis

G Model CULHER-3355; No. of Pages 7 ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Cultural Heritage xxx (2017) xxx–xxx Available online at ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com Original article Protecting Yazidi cultural heritage through women: An international feminist law analysis a,b,∗ Sara De Vido a Ca’ Foscari University, San Giobbe, Cannaregio 873, 30121 Venezia, Italy b Manchester International Law Centre, UK a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The purpose of this article is to consider, from an international law perspective, the relationship existing Received 25 May 2017 between violence, gender, and culture, referring to the specific situation of women belonging to the Yazidi Accepted 12 February 2018 minority, who have been abducted, raped, and sold by the Islamic State. I will demonstrate that women Available online xxx can be those who, despite huge suffering, will be able to preserve the unique culture of this minority during post-conflict situations. From an international law perspective, I will investigate the possibility Keywords: that the crimes committed against the Yazidis are brought before the International Criminal Court, and Yazidis I will recommend that a women’s tribunal be established in order to give voice to the victims/survivors. Women I will demonstrate that the participation of women during the negotiations for peace in post-conflict Violence situations is essential, and that the protection of intangible cultural heritage through women could be Intangible cultural heritage Criminal justice achieved learning the lesson from preceding successful experiences. Women’s tribunals © 2018 Elsevier Masson SAS. -

Kirkuk and Its Arabization: Historical Background and Ongoing Issues In

Abstract The Arabization of the Kurdistan region in Iraq Since the establishment of the Iraqi state, the ruling Arab regimes forcibly displaced native Kurds and repopulated the area with Arab tribes. The change of demography,known as “Arabization,” existed in both Kurdish majority agriculture and urban lands. These policies were part of a larger Iraqi campaign to erase the Kurdish identity, occupy Kurdistan, and control its wealth. The Iraqi government’s campaign against the Kurds amounted to genocide and eventually destroyed Kurdish communities and the social fabric of Kurdistan. The areas affected by the Arabization stretch from eastern to northwestern Iraq , incorporating major cities,towns, and hundreds of villages. After the fall of Saddam Hussien’s dictatorship, these areas became referred to as “Disputed Territories'' in Iraq’s newly adopted constitution of 2005. Article 140 of Iraq’s constitution called for the normalization of the “Disputed Territories,” which was never implemented by the federal government of Iraq. 1 www.dckurd.org Kirkuk province, Khanagin city of Diyala province, Tuz Khurmatu District of Saladin Province, and Shingal (Sinjar) in Nineveh province are the main areas that continue to suffer from Arabization policies implemented in 1975. KIRKUK A key feature of Kirkuk is its diversity – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians (Chaldeans and Assyrians) all co-exist in Kirkuk, and the province is even home to a small Armenian Christian population. GEOGRAPHY The province of Kirkuk has a population of more than 1.4 million, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Kirkuk city. Kirkuk city is 160 miles north of Baghdad and just 60 miles from Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan region. -

Yazidis and the Original Religion of the Near East | Indistinct Union: Chri

Yazidis and the Original Religion of the Near East | Indistinct Union: Chri... http://indistinctunion.wordpress.com/2007/08/17/yazidis-and-the-original... Indistinct Union: Christianity, Integral Philosophy, and Politics Yazidis and the Original Religion of the Near East The horrific bombing in the Kurdish regions around Kirkuk (death toll estimates currently at 400) targeted the Yazidis, a smallish Kurdish (but non-Muslim) sect. The Ys tended to separate themselves from the Peshmerge (the Kurdish military), which likely resulted in their being left vulnerable to this brutal attack. (For interviews with some Yazidis, here via BBC). Who are theologically the Yazidis ? For repeat readers, they will know I support the (somewhat) controversial thesis of Christian scholar Margaret Barker (known as Royal Temple Theology). Barker’s first work is titled The Older Testament. A brilliant way to describe her point of view–namely that the Judaism that comes across in the Hebrew Bible we currently have has been massively (re)edited, more than most scholars will admit, by the Deuteronomic/Rabbinic schools of Judaism. The Older Testament (as opposed to the “Old Testament” of the Deutro. school) included the belief in two g/Gods. The first was the High God (El, Elyon) who had “sons” (angelic beings). Each angel, known as an angel of the nation, was chosen for a specific people. As above so below. i.e. When their was war on earth between two peoples, their angels were fighting in heaven. Hence all the Psalms rousing YHWH (Israel’s Angel/god) to fight. The second G/god then is YHWH for Israel. -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

IRAQ: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) for HRP and Non-HRP Activities January to June 2021

IRAQ: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) for HRP and Non-HRP Activities January to June 2021 TURKEY 26 Zakho Number of partners by cluster DUHOK Al-Amadiya 11 3 Sumail Duhok 17 27 33 Rawanduz Al-Shikhan Aqra Telafar 18 ERBIL 40 Tilkaef 4 23 8 Sinjar Shaqlawa 57 4 Pshdar Al-Hamdaniya Al-Mosul 4 Rania 1 NINEWA 37 Erbil Koysinjaq 23 Dokan 1 Makhmour 2 Al-Baaj 15 Sharbazher 16 Dibis 9 24 Al-Hatra 20 Al-Shirqat KIRKUK Kirkuk Al-Sulaymaniyah 15 6 SYRIA Al-Hawiga Chamchamal 21 Halabcha 18 19 6 2 Daquq Beygee 16 12 Tooz Kalar Tikrit Khurmato 12 8 2 11 SALAH AL-DIN Kifri Al-Daur Ana 2 6 Al-Kaim 7 Samarra 15 13 Haditha Al-Khalis IRAN 3 7 Balad 12 Al-Muqdadiya Heet 9 DIYALA 7 Baquba 10 4 Baladruz Al-Kadhmiyah 5 1 Al-Ramadi 9 Al-Mada'in 1 AL-ANBAR Al-Falluja 24 28 Al-Mahmoudiya Badra 3 8 Al-Suwaira Al-Mussyab JORDAN Al-Rutba 2 1 WASSIT 2 KERBALA Al-Mahaweel 3 Al-Kut Kerbela 1 BABIL 5 2 Al-Hashimiya 3 1 2 Al-Kufa 3 Al-Diwaniya Afaq 2 MAYSAN Al-Manathera 1 1 Al-Rifai Al-Hamza AL-NAJAF Al-Rumaitha 1 1 Al-Shatra * Total number of unique partners reported under the HRP 2020, HRP 2021 and other non-HRP plans Al-Najaf 2 Al-Khidhir THI QAR 2 7 Al-Nasiriya 1 Al-Qurna Suq 1 1 2 Shat 119 Partners Al-Shoyokh 3 Al-Arab Providing humanitarian assistance from January to June Al-Basrah 3 2021 for humanitarian activities under the HRP 2021, HRP 2020 AL-BASRAH Abu SAUDI ARABIA AL-MUTHANNA 4 1 other non-HRP programmes.